———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday November 6, 1910

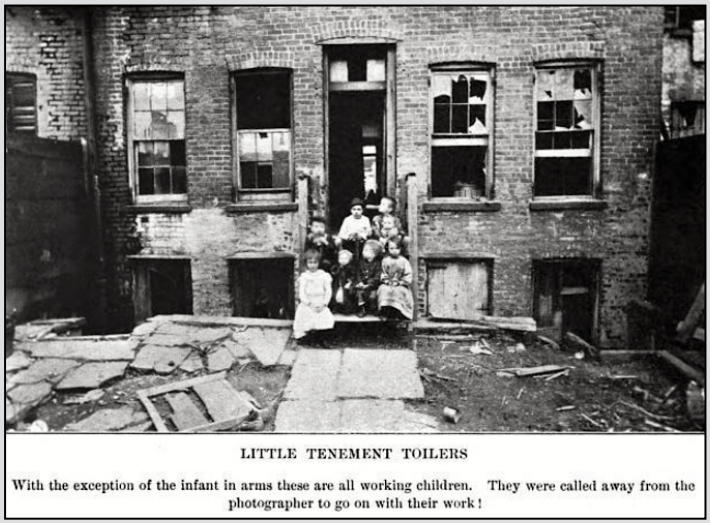

Ohio Labor Investigation – Report on Sweatshops from 1893

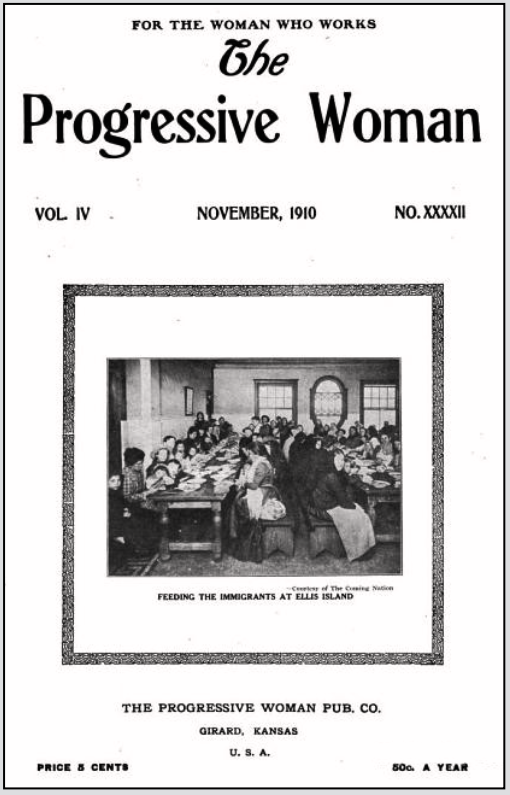

From The Progressive Woman of November 1910:

THE SWEATING SYSTEM

MARY L. GEFFS

Special Investigator for the Bureau of Labor Statistics of Ohio, 1893Origin of Title.

It is not definitely known what gave the system its title, but it is safe to hazard a guess that it was the sheer aptness of the word ”sweating” to describe the condition. For many of the shops and tenements where the work is carried on are veritable bake ovens. They are often found in attic rooms where the summer sun beats down unmercifully upon the roof but a few feet above the toilers’ head, where the heat of charcoal stoves and the steam and heat of irons needed in pressing, together with a total lack of proper ventilation render anything less than sweating impossible. It may, therefore, be to the over-doing of the command said to have been given to the First Pair, “in the sweat of they face shalt thou eat bread,” that this title is due, but it might with equal fitness express the orthodox idea of the abode of the lost, for, in all the range of woman employing industries, not only are there few so hot, but fewer still so hard, so unremunerative, so slavish, nor whose baneful effects are so wide-spread and far-reaching as that known by the title of “The Sweating System.”

What it is and How It Operates.

This system is that by which garments are cut in the big factories and given out to be made in the shops or homes of the workers. The work is paid for by the piece or by weekly wages based on the piece, and prices are reckoned according to the iron law of wages. That is, as near as possible to the life limit; the lowest point at which the workers can live and continue to produce. They are so low that long hours must be put in every day in order that the workers may eke out a bare existence.

The Good That is Claimed for It.

The good that is claimed for this system is that it enables mothers of young children, or with invalids under their care, to earn a living at home while at the same time caring for the helpless ones in their charge. Also, that it enables poor men to enter the business world, and, with very little capital to begin on, to build up a comfortable fortune.

Both claims are true; but at what cost?

Two typical cases, actually visited, will illustrate:

How the Good Points Appear When Investigated.

First, let us go to the home of the mother of a family. It is in one of the big tenement houses of Cincinnati, a class of human live which abounds in all big cities of the state. It is on the third floor and is, therefore a degree better in point of heat than the attic above. It consists of two small rooms. The room where the sewing is done is kitchen, sewing room and bed room for part of the family. Its one small window opens out onto a narrow porch beyond which is the high wall of another building; and it is shaded by another porch belonging to the floor above. There is but a narrow slit of light by which to work, and ventilation is unworthy the name. The other hole in the wall, by courtesy called a room, is almost wholly dark, its one window opening on to a dingy court-way where the sun penetrates only at noonday.

The family consists of crippled husband, wife and three small children. The wife makes the living for the family, and here we will find the “good” features of the system in full force. She takes care of her children and sick husband and still earns a living for her family. What a boon to her must be the sweating system. But let us inquire how she gets on. Listen; she’s telling us:

She makes luster coats at eighteen cents each. She gets the work ready cut from the contractor and returns the garments finished. She bears the expense of transporting the work both ways; that is, she would bear the expense if she could afford it, but she can’t, so she makes the trip herself to and from the factory, carrying the heavy bundle both ways. The loss of time alone is no small item, often equalling the price of a coat or more.

The business of the contractor is so systemized that each worker has a certain day in the week on which to bring back finished garments and take out new work. Necessarily a good many have the same day; so when our worker gets there all she can do is to await her turn. She may wait half an hour; she may wait half a day. She may grow restless thinking of the helpless ones at home or the precious moments wasting; but it matters not; she would not be received on any other day than the one allotted, so there is nothing to do but wait.

At last her turn arrives; her work passes under the eye of the inspector, and she waits with bated breath and many forebodings while the search for faults goes on. Whether or not faults are found often depends more upon the humor of the inspector than upon the condition of the work. Inspectors may be soured by the system, by coming into daily contact with those for whom they need cultivate no respect, or, they may be over zealous to please their employers; but be the cause what it may, the fact remains that about ninety-nine out of every hundred are crabbed and unkind and never seem so happy as when finding fault. Real faults there doubtless are sometimes, but even when these faults are no more than the tacking of a button hole or the better sewing on of a button, jobs that would take but a moment’s time, the work is thrown back on the hands of the worker—or into her face, as actually happened—and she is ordered to take the work home and do it over and return it the following week. This means twice more carrying it over the road, and waiting for her money another whole week. But there is no appeal; the inspector is an absolute autocrat in his realm, and she dare not quarrel with him for fear of losing her work altogether.

Two coats per day are as many as she can hope to finish with her other duties. Thirty-six cents per day. All but the barest necessities must be cut out. The children know not the taste of sugar. The crippled husband indulges in no hope of medical assistance other than the experimentation of charity doctors. The mother hopes for nothing except that work will not fall off. Life has no sunbeams; it has only the grayness of want, despair and suffering. And so the beneficent features of the system fade away at the closer touch, leaving revealed only some of the saddest tragedies in the lives of earth’s lowly toilers.

How the Sub-Contractor Gets Rich.

Come, next, to a shop in Cleveland where the other claim, that a poor man may enter business and get rich, is verified.

This shop is conducted by a man who, according to his statement, began a few years ago with barely enough saved from his earnings to pay a month’s rent on a shop; now he has a neat and constantly growing bank account and looks forward with confidence to the time when he will become a manufacturer. He is a sub-contractor; an employing employe. In relation to the big manufacturer from whom he gets his work he is an employe; and in relation to those under him who do the work he is an employer. Some day he will buy up a stock of goods, cut the garments in his own shop and be an employer only; a manufacturer; a captain of industry; then the whole profit will be his, and his road to fortune will be straight. He is in business for what there is in it, and lays no hypocritical claims to philanthropical motives. He might call in other men as poor as himself and together they might share the profits, but that would not be good business. He applies strict business principles to the enterprise; he plays the game according to the rules; and the result is that his sh0p is filled with girls who must make a living.

Ostensibly he pays weekly wages, but the sum paid, which seldom reaches above $2.50, is based upon the following calculation: The class of work on which he is engaged is ladies’ coats for which the manufacturer pays him sixty cents each. A girl, to be worth $2.50 per week to him, must make at least two coats per day, $1.20. In two days she has virtually earned all she is to get for the whole week, and the other four days are absolutely clear profit to her employer. Or, in other words, for the opportunity of earning $2.50 for herself she must pay $4.70 to the man who gives her the opportunity. (i. e., two coats per day, $1.20, six days in the week, $7.20, $2.50 due her in wages, leaves $4.70 to the employer.) She would not receive $2.50 if she produced less than $4.70 in profits to her employer. So after all her weekly wage is only seeming; she really gets, leaving off fractions, twenty cents for making a heavy coat, while her employer gets forty cents for allowing her to make it.

Yes, the claim is absolutely well founded that a shrewd and energetic business man may enter the business and soon get rich.

An incident that actually occurred a few days prior to the visit of the investigator to this particular shop will show under what high pressure a $2.50 a week girl, tasked with the production of two coats per day, must work:

The sewing machines were run by foot power; the hours of labor were from 7 a. m. to 6 p. m. with half an hour at noon for lunch; the stove, covered with hot irons used in pressing, was kept going at full blast all day; it was in mid-summer and mercury marked high among the nineties; the shop was intensely hot. The “boss” noticed one of the girls lagging and called out to her above the din of the machinery.

“Go ahead there; what are you stopping for? You can make your legs go faster; faster, do you hear?”

The girl heard and went “faster,” and the next moment lay in a dead faint on the floor. Her shopmates looked on in pity but dared not leave their machines nor say “a word. The “boss” was annoyed, for now some one’s valuable time must be wasted in getting the girl out of the way; but there was no help for it, so he called a man and together they dragged her to a corner of the room and dropped her upon a pile of scraps and unfinished garments. No further attention was paid to her, but after a while the swoon passed off and in about an hour she dragged herself back to her machine and went to work. But—at the end of the week when her check came to her she found that she had been docked for the hour’s time lost while lying unconscious.

The Fining System.

The system of fines or docking, which however is not confined to the sweat shops but is found in other industries as well, is a most prolific source of revenue to the bosses, but often entails great hardships upon the girls. Fines for being late in the mornings sometimes run as high as one cent per minute, yet if a rush of business occurs and the girls are obliged to stay over time in the evenings no extra pay is allowed them. Fines are imposed for faults in the work, yet those responsible for the faults are compelled to make them good as well as submitting to a fine. Girls have been interviewed whose wages, through fines, have been reduced as low as fifty cents per week.

Spread of Disease Under the Sweating System.

The sweating system is a constant menace to the health of the people, and is, without doubt, responsible for the spread of many diseases, chief among which is tuberculosis. Particularly is this true of work done under tenement conditions. Why?

Because in most cases where women take work into their homes it is because either they themselves are too far spent with disease to stand the heavy tasking that would be put upon them in the shops, or some member of their family is too sick to be left alone. The contractor who gives out the work asks no questions as to the health or sanitation of the place into which it is to go, and the workers could hardly be expected to volunteer information that might possibly rob them of their only chance to ward off starvation. Hence, it is no unusual occurrence for unfinished garments to lay for days and nights on the foot of a bed occupied by a tubercular patient. Children pass through scarlet fever, whooping cough, dypyheria and even small pox in the same room and the same bed with garments that are to go out and enter, unfumigated, into the arteries of trade.

Nor is this all. Away back of this, disease may be traced. The cloth used in the grade of clothing usually made up under the sweating system is made in large part from what is known as “shoddy.” The material for this is gathered promiscuously by the rag pickers in the streets and consists largely of odds and ends of old clothing, bedding, mattresses, bandages from old sores, etc., nothing so rotten, so dirty, so disease laden but can be utilized. This conglomerate mass is hauled to the factory and dumped into a flaying machine and the dry dirt beaten out of it, or into it, as the case may be. Then it is passed into another machine that picks it into pieces so small that not one fiber is left attached to another. Then it is carded, spun, dyed, woven into cloth and sent out to the dealer, thence to the manufacturer who cuts it into garments and passes it on to the sub-contractor who, as already shown, sends it back to the disease ridden tenement house for its final inoculation. And nowhere, from start to finish, is there a process of purification.

And disease spreads, and the sleeping health authorities wonder why.

—————

For home work among the cotton mills of the north the average income is 48 cents a day, or $175 per year; in the south it is 34 cents a day, and $125 a year.

—————

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Mother Jones, Wake fr Slumber, AtR p2, Oct 23, 1909

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/appeal-to-reason/091023-appealtoreason-w725.pdf

The Progressive Woman

(Girard, Kansas)

-Mar 1909 to May 1911)

(some issues missing)

https://books.google.com/books?id=Zo1EAQAAIAAJ

Nov 1910

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Zo1EAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA20-PA17

page 3-“The Sweating System” by Mary L. Geffs

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Zo1EAQAAIAAJ&pg=GBS.RA20-PA3

See also:

Search Source above: “sweat shop”

https://books.google.com/books?id=Zo1EAQAAIAAJ

Diary of a Shirtwaist Striker

-by Theresa Serber Malkiel

https://books.google.com/books?id=ufUOAAAAIAAJ

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=ufUOAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA1

https://archive.org/details/diaryashirtwais00cogoog/page/n4

2nd ed 1910

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015073391321&view=2up&seq=8

The Bitter Cry of the Children

-by John Spargo

Macmillan, 1906

https://books.google.com/books?id=5qSXMJQG6E4C

Tag: Bitter Cry of the Children

https://weneverforget.org/tag/bitter-cry-of-the-children/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dortn iz mayn rue plats/There is my resting place