———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday April 29, 1919

Seattle General Strike: Revolution? -60,000 Striking Workers Run the City

From the New York Liberator of April 1919:

When Is a Revolution Not a Revolution

Reflections on the Seattle General Strike

by a Woman Who Was There

“A GENERAL STRIKE, called by regular unions of the American Federation of Labor, cutting across contracts, across international union constitutions, across the charter from the American Federation of Labor,”-this was what the chairman of the strike committee declared it to be. A General Strike in which the strikers served 30,000 meals a day, in which the Milk Wagon Drivers established milk stations all over town to care for the babies, in which city garbage wagons went to and fro marked “Exempt by Strike Committee”; a General Strike in which 300 Labor Guards without arms or authority went to and fro preserving order; in which the Strike Committee, sitting in almost continuous session, decided what activities should and should not be exempted. from strike in the interests of public safety and health, and even forced the Mayor to come to the Labor Temple to make arrangements for lighting the city.

Yet almost any member of the Strike Committee will tell you, in hot anger, that “this was no revolution, except in the Capitalist papers; it was only a show of sympathy and solidarity for our brothers in the shipyards.” And so in truth it was, in intention. It would seem that the beginnings of all new things take place, not through conscious intention, but through the inevitable action of economic forces.

Hardly yet do the workers of Seattle realize all the things they did.

The shipyard workers of Seattle struck, 35,000 strong, on [Tuesday] January 21st. On January 22, a request was brought to the Central Labor Council for a general strike in sympathy with the Metal Trades. This was referred to the various unions for referendum. By the following Wednesday, January 29, the returns were pouring in.

“Newsboys vote to strike and await instructions of Joint Strike Committee.” “Hotel maids vote 8 to 1 for strike.” “Waitresses expect to go strong for general strike.” Foundry employees, butchers, structural iron workers, milk wagon drivers, garment workers, carpenters, barbers, building laborers, longshoremen, painters, glaziers, plasterers, cooks and assistants, these were among the votes to come in the first week.

On Sunday [February 2] delegates from 80 unions met as a General Strike Committee. They were a new group, unused to working together, and almost without exception from the rank and file. They selected a committee of fifteen as Executive Committee, and from that time to the end of the strike there was hardly a moment day or night in which either the General Committee or the Executive Committee was not on the job at the Labor Temple.On Thursday [February 6] at 10 A. M. the strike was called. Even the local press declared that the city “was prostrate,” that “not a wheel turned for 24 hours.” Soon the strikers themselves began to discover- an embarrassment in the very completeness of the strike. They were learning that there is another solidarity than that of labor, the solidarity of the consuming public of which they also were part. They were faced almost at once by the necessity of deciding a vast number of questions which might be summed up in one: “Were they striking against the business-men, or against the community? Did they want to make people as miserable as possible, or only to interfere with profit?”

The workers were carrying on a strike, not a revolution. They had no intention of ruining their home town, or reducing it to a state of siege. They did not propose to destroy anything; but only to run things for a little while, and take the whole town with them on a vacation.

Take for instance the Laundry Workers. Serving notice on their bosses that they were going to strike on Thursday, and that no more laundry should be taken in, they at the same time asked, and were granted, permission to work long enough on Thursday to finish the clothes in the laundries, lest they spoil with mildew. Then they arranged, by consultations with the Laundrymen’s club (the employers) that one laundry should remain open for hospital work, and that a sufficient number of wagons should be exempted to carry hospital laundry. This complete program, carefully organized, was presented to the Strike Committee and authorized.

The Milk Wagon Drivers attempted to arrange with the Milk Dealers for a complete system of milk stations all over the city to supply babies. Finding that the Milk Dealers were disposed to run the affair themselves, the Divers withdrew and let the Dealers sell milk at the various dairies while they established neighborhood milk stations. The Milk Dealers asked the Drivers Union to endorse their application to the Strike Committee for one one auto-truck permit to get their milk into the city, and the Drivers graciously agreed!

A request from the county commissioners that janitors be allowed to keep the county-city building clean was denied; also a request that janitors be allowed to keep the Labor Temple in sanitary condition. The Strike Committee was playing no favorites. But whenever a request arrived involving the care of the sick, it was granted without more ado. Janitor after janitor who called up to report that there were cases of “flu” in his apartment house and that he wished to remain on the job, was permitted to do so.

Page after page of requests for exemption, granted or refused, fill the minutes of the Strike Committee.

For example:

Teamsters request permission to haul oil to the Swedish Hospital during strike. Concurred in.

City Garbage Wagon Drivers apply for instructions and are given permits to gather such garbage as tends to create epidemics, but no ashes or papers.

Drug clerks apply for instructions and are told that they are permitted to fill prescriptions only, and that in front of every drugstore left open, signs must appear that no goods are sold during general strike, but prescriptions are filled by order of strike committee.

House of Good Shepherd granted permission to haul food and provisions only.

Trade Printery applies for exemption for printing for unions. Not granted, but the Printery is asked to turn over its plant to the Strike Committee and the printers are asked to contribute their services. This request is granted by the Trade Printery.

Auto Drivers allowed to answer calls from hospitals or funerals, providing such calls go through their union.

Bake ovens at Davidson’s Bakery allowed to operate, all wages to go into the general strike fund.

Solidarity developed to an amazing degree during the strike. The Japanese and American restaurant workers went out side by side. The Japanese barbers struck when the American barbers struck, and were given seats of honor at the Barbers union meeting which occurred immediately thereafter.

Members of the I. W. W. were granted, by vote of the General Strike Committee, the same privileges in the eating houses that were possessed by members of regular unions. And the I. W. W.’s responded with the promise that if any of their members were found causing trouble, they would put them out of town and keep them out, as “they intended to show the A. F. of L. that they could join in a strike and cause no disorder.”

One hundred and eleven Local Unions of the A. F. of L. took part in the strike. How many individual workers struck without the protection of a union will never be known, but there were many. There came to my notice an elevator boy in an office building who calmly quit, saying that he hoped to get his job back again, but he wasn’t going to work during the strike. Two men working for a landscape gardener did the same, and lost their jobs. Newsboys arose in school and left on Thursday at 10 A. M. Much spontaneous action of this kind occurred all over the city.

The mayor went about the task of preserving the peace in the time-honored way. Machine guns came into town, large numbers of troops were brought over from Camp Lewis and quartered in Seattle, 600 special police were employed by the city and 2,400 volunteer “special” police were hastily sworn in.

But despite all the usual provocations to violence, the strikers did not retaliate; 60,000 men were out for five days without a single arrest in connection with the strike. Why ? Because, while the authorities prepared for violence, the workers organized for peace.

“It was the members of organized labor who kept peace and order during the strike. To no one else belongs the credit.” These are the words of Robert Bridges, President of the Port of Seattle.

“Labor’s War Veteran Guards” -this was the name given to the organization formed by labor to police the strike. All labor men who had seen service in the U. S. Army or Navy were invited to join. The purpose of the organization was “to preserve law and order without the use of force.” Its first rule was that “no member shall have any police power or be allowed to carry any weapons.” Men who could have received good pay from the city police as special officers, preferred to give their services free to labor, in return for two meals a day.

They worked in cooperation with the police; but their standards were higher. While the police would allow threatening crowds to gather, crowds which might become a riot-the Labor Guards would mix quietly with the bunch and say: “Brother working-men, this is for your own good. We don’t want crowds that will give the machine guns a chance.”

“You’re right, brother,” would come the answer, and the throngs would scatter.

Even when the city car-line started, with armed men in the cars, the Labor Guards succeeded in dispersing the irritated crowds. A state of such peaceful strength was brought about that self-important youths swinging big sticks could pass right through crowds at the Labor Temple and receive good-natured, ironical smiles from men who refused to be angered. “It is your smile that is upsetting their reliance on artillery, brother,” was the theme of many a Strike Bulletin editorial. And indeed it was the fact that “nothing happened” that perplexed the business men and the authorities most.

When after five days, announcing that the main objects of the strike were accomplished, the General Strike Committee called off the sympathetic strike, most of the men went back to work in good spirits, realizing, not indeed that they had won the recognition of the shipyard workers which they had asked for, but that perhaps they had done something bigger. They had educated the City of Seattle in the knowledge of its dependence on labor; they had learned much in the process. They had had an intimate contact with the interrelation of the city’s industries and the city’s life; they knew the sources of food, and what happens when City power goes off. They had come close “to the problem of management.” They had done it all quietly, without a touch of violence~ without an arrest.

They went back to the old relations. But the Milk Wagon Drivers have faced the problem of running the milk business of the town. They know it; and their bosses know it. And the Cooks have faced the problem of provisioning a city. And the barbers are starting a chain of cooperative barber shops. And the plumbers have opened a profitless grocery store. And the Labor War Veteran Guards are forming a permanent organization for the policing of labor, dances, labor parades and strikes.

No, it wasn’t a revolution! “The seat of government is still at the City Hall” boasts Mayor Hanson. Yet more than one business man, riding to town in his auto, looked at the garbage wagon marked “Exempt by Strike Committee” and said bitterly: “There goes the new government!”

(It is impossible to keep up with Cooperation in Seattle. Just as we go to press word comes of a Cooperative Bank opened March 1st in which the workers of Seattle deposited $$1,000,000 the first day!)

———-

[Emphasis and photograph added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote Anna Louise Strong, NO ONE KNOWS WHERE, SUR p1, Feb 4, 1919

http://depts.washington.edu/labhist2/SURfeb/SUR%202-19-4%20full.pdf

The Liberator Internet Archive

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-Apr 1919, page 23

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/04/v2n04-apr-1919-liberator.pdf

Note: I believe the above article may have been written by Anna Louise Strong, more research needed.

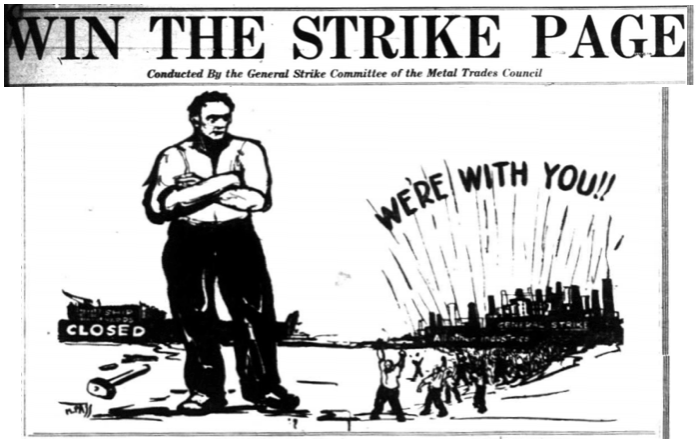

IMAGE

Seattle General Strike, Metal Trades Council, SUR p3, Feb 4, 1919

http://depts.washington.edu/labhist2/SURfeb/SUR%202-19-4%20full.pdf

See also:

From CounterPunch of Feb 8, 2019:

“The Seattle General Strike: a 100-Year Legacy”

-by Cal Winslow

https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/02/08/the-seattle-general-strike-a-100-year-legacy/

Tag: Seattle General Strike of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/seattle-general-strike-of-1919/

The Seattle General Strike

“An Account of What Happened in Seattle and Especially

in the Seattle Labor Movement, During the General Strike,

February 6 to 11, 1919″

-Issued by the History Committee

of the General Strike Committee

[Historian, Anna Louise Strong]

The Seattle Union Record Publishing Co. Inc., 1919

https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/pioneerlife/id/9157/rec/1

Tag: Anna Louise Strong

https://weneverforget.org/tag/anna-louise-strong/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Solidarity Forever- NYC Labor Chorus at 2017 Clara Lemlich* Awards

Lyrics by Ralph Chaplin

-wondering today about Ralph Chaplin-could he imagine then, as he languished in Leavenworth Prison in 1919, that we would still be singing his song 100 years later?

*Clara Lemlich

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Lemlich