———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday April 30, 1919

From Appeal Book Department: “The Unbroken Tradition” by Nora Connolly

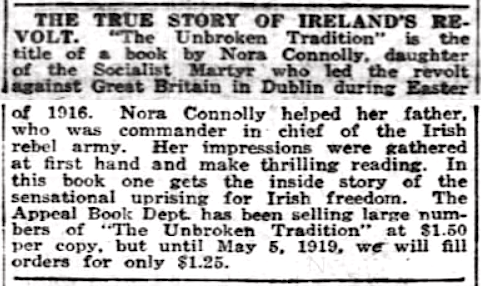

In the April 26th edition of the Appeal to Reason, we find Miss Nora Connolly’s book, “The Irish Rebellion of 1916 or The Unbroken Tradition,” on sale for $1.25 (see below). In the April 12th edition of the Appeal we find a review of Miss Connolly’s book along with a short history of the Easter Uprising of 1916.

From the Appeal to Reason of April 12, 1919:

Daughter of Rebel Leader Tells Story of Irish Revolt

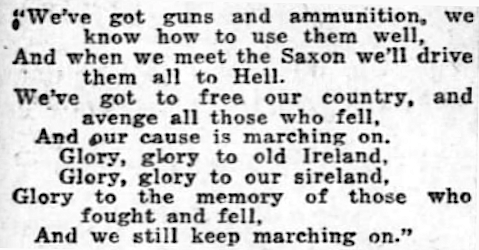

—–Thus goes one of the fighting songs of the Irish patriots who rose in armes against British authority in Ireland, the week of Easter, 1916. The physical failure of the brief, spirited upflare of independence is now a part of Ireland’s tragic history; yet today no one who sees clearly can doubt that the cause of a free Ireland is stronger than ever.

Nora Connolly-a young girl possessed of the fortitude and vision that is the unending marvel of character displayed by all true revolutionists-was an intimate participant in the rebellion of 1916. Her father, James Connolly, was the leader of the rebel forces and was executed for his “treason” to what most Irishmen have always regarded as an alien and hostile government. Nora Connolly escaped after the rebellion and made her way, through caution and subterfuge, to America. Here she set down the story of this ill-fated uprising with a direct candid simplicity that reveals events in their bold, epic outlines. This story, whose unaffected realism is so intense that the reader vividly visualizes and emotionally seems to move in the very midst of the scenes described is called “The Unbroken Tradition,” because, says Nora Connolly:

In Ireland we have the unbroken tradition of struggle for our freedom. Every generation has seen blood spilt, and sacrifice cheerfully made that the tradition might live. Our songs call us to battle or mourn the lost struggle; our stories are of glorious victory and glorious defeat. And it is through them the tradition has been handed down till an Irish man or woman has no greater dream of gory than of dying “A soldier’s death so Ireland’s free.”

* * *

THE SIGNIFICANT feature of the Irish struggle (even during the periods of apparent peace) is that it has not been parliamentary; it has been frankly militant, relying finally upon force. The Irish people have been thoroughly imbued with the idea that the liberty of a people must be the result of its own efforts-more, that it depends upon preparation and willingness to engage in actual fighting. The Irish are great talkers, but they are even greater fighters. Their history proves this. Six times during the English occupation of their country the Irish people have broken out in open, armed revolt; and the intervals between these outbreaks have been devoted to organization and training for the next uprising, which is considered as inevitable.

During the memorable Dublin strike of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in 1912-13, the Irish Citizen Army (composed entirely of union workingmen) regularly practiced military drill in an open field and marched in military formation through the streets of Dublin. Liberty hall, the headquarters of the union, was the scene of daily demonstrations. This army had a commissary department in Liberty Hall, where the strikers and their families were fed and clothed. The great strike was won by the workers, but they did not cease their struggle for a free Ireland.

Following the organization of the Irish Citizen Army came the organization of the Irish Volunteers, which included all Irish patriots who were ready to pledge themselves in the larger cause of national independence. These two voluntary military organizations drilled continuously, the workers going through their manouvers in the evening after the day’s hard toil. Sham battles were held between the two rebel bodies. Lectures were given by the rebel leaders on the art of street fighting. Everything was in dead earnest; few details were omitted.

One of the important tasks of the rebels was to secure guns and ammunition, which were smuggled into the country. In July, 1914, just before the world war descended upon Europe; one of these gun-running expeditions had a bloody finale. A number of rebels assembled at the landing place, among them many rebel boy scouts, the arms were brought ashore, and, after each rebel had been given a weapon, were loaded into automobiles and carried away. While the guns were being unloaded, a line of rebels armed with clubs stood across the pier to resist police interference with their lives if need be. The gun-runners were attacked by a small body of soldiers and police, but the latter were heroically beaten off. These defenders of the King then fired into the crowd, shooting down several women and children. But the rifles-three thousand of them-were saved.

The victims of this tragedy were given a spectacular funeral. The union and rebel organizations marched behind the hearses. Added to these were many of the unorganized citizens of Dublin, sympathetic with the rebel cause but not actively belonging to it. The union band of the Irish Transport Workers played the funeral march. Walking behind one of the hearses, the chief mourner, was a man in the uniform of an English soldier. His old mother had been killed by other men wearing the uniforms of English soldiers. This funeral was one of the greatest demonstrations ever held in the city of Dublin. So bitter was the feeling against the regiment that had shot among the populace that these troops were quietly withdrawn from the city.

* * *

A WEEK after the shooting-while the memory of it still burned in the hearts of Irish people-the world war came. Immediately England called upon Irishmen to enlist in the struggle to avenge Belgium. How empty this appeal seemed to the Irish patriots may be imagined. Their minds were occupied with the outrages they had themselves to avenge. The Prime Minister, Mr. Asquith, and the Irish parliamentary leader, John Redmond, came to Dublin with the purpose of holding a monster recruiting meeting. The Dublin rebels held a counter-demonstration. A gigantic parade went through the streets of the city shouting defiance and singing anti-recruiting airs; in the midst of it was an automobile, surrounded by members of the Irish Citizen Army with rifles in their hands, from which speakers poured forth demonstration after demonstration against Great Britain and recruiting. Within a block of the hall where the British Prime Minister was holding forth, James Connolly called upon the crowd to declare its allegiance to an Irish Republic and the mighty shout that went up in response drowned out the voice of the Prime minister in the nearby hall. Nora Connolly says that only six Irishmen joined the British army the next day. England’s blind, oppressive policy with the Irish sharply alienated these brave people when England entered upon the greatest war of her history and western civilization was threatened. Those who viewed the war calmly and logically as a vast world struggle in which one must be on the side of autocracy or democracy failed to understand that the Irish people, with a heritage of hatred against the British government, could not take any such detached and rationalistic attitude. Their whole emotional and national perspective was focused hostilely on their historic oppressors. This situation, created by British rule, culminated in the open rebellion of Easter week.

* * *

THE REBELLION, which had been planned to take place simultaneously throughout Ireland, was at the final moment confined to Dublin and one or two outlying districts. Through an eleventh-hour slip in the plans for a general uprising, the rebellion was doomed to failure. Nevertheless the fighting raged in Dublin for nearly a week. Connolly and his comrades led the rebels until the last hope died and surrender was made imperative. The headquarters of the rebel forces was the general postoffice, though they had outposts over the city. The rebels were handicapped by having only rifles, while the government troops had machine guns. The streets were barricaded by the soldiers and the roads leading to Dublin were patrolled by the King’s men.

Yet Nora Connolly tells how she and her sister managed to elude these patrols, and how they walked over fifty miles to Dublin, only to arrive after the rebel cause had been lost and their wounded father made a prisoner. These daughters of the rebel leader had gone to another part of Ireland, near Belfast, to assist in the rebellion there. Owing to a demobilization order sent out by Eoin MacNeill, civilian President of the Irish Volunteers, on the day before the uprising was to occur, only the Dublin rebels rose. It was then that Nora Connolly and her sister undertook their long, weary hike back to Dublin.

Eoin MacNeill, whose demobilization order “broke the back of the rebellion” according to the statement of the British authorities, was a Professor of Irish History supposed to be a safe conservative by the British government. He was a prudent academic revolutionist; he believed in a free Ireland, but advised “watchful waiting.” He was made President of the Irish Volunteers chiefly because his respectable character would serve as a blind to the true purpose of the organization. Through the organ of the Irish Volunteers MacNeill advocated delay and caution, emphasizing his belief that the most propitious time for action would be after the end of the world war, when the organization would be solid and strong. The Volunteers interpreted these articles as merely dust thrown in the eyes of the British government and waited expectantly for “the day.”

Just before the appointed time for the rebellion, Sir Roger Casement, who had gone to Germany for assistance and there had heard that the uprising was to take place immediately, and who was unaware how far the plans and preparations of the rebels had gone, came to Ireland in a German submarine with the object of warning the rebels to post their attempt. Landing on the Irish coast, he quickly dispatched a message to MacNeill, telling him that the rebellion would fail if attempted then and advising that the men be called off. MacNeill, naturally fearful, had his worst misgivings excited by Casement’s communication and promptly sent out the demobilization order. On Sunday-the before “the day”-he also inserted a notice in the organ of the Irish Volunteers, which circulated throughout Ireland, to the effect that:

All Volunteer manouvers for Sunday are canceled. Volunteers everywhere will obey this order.

MacNeill acted in good faith, but he was lacking in courage and determination.

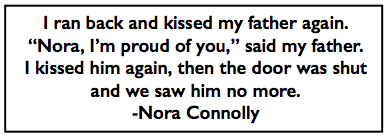

When James Connolly and the rebel leaders in Dublin learned of MacNeill’s action , they dispatched Nora Connolly and her sister with a message to the rebel leaders out Dublin. But it was too late. The back of the rebellion had been broken. After fighting to the last ditch, their leaders were executed and another bloody page was added to the history of Ireland’s struggle for freedom. James Connolly, the moving spirit of the rebellion, was wounded in the Dublin fighting. He was placed on a chair and shot before he had recovered from his wounds. Before he was executed he slipped a copy of his dying statement to his daughter Nora, who gives it to the world in her story of “The Unbroken Tradition.” How Nora Connolly came to America and was thus enabled to publish the uncensored record of the Easter uprising, she tells in her book.

———-

[Emphasis and photograph of Miss Nora Connolly added.]

From the Appeal to Reason of April 26, 1919:

Great Book Sale Closes in One Week

[…..]

[…..]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

Quote Nora Connolly, We saw him no more. UnBroken Tradition p186, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=G2umZxhfRhMC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA186

Appeal to Reason

(Girard, Kansas)

-Apr 12, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67587330/?

-Apr 26, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67587347/

IMAGE

Nora Connolly, Unbroken Tradition p88, BnL, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=G2umZxhfRhMC&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA88-IA1

See also:

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday March 16, 1919

From The Appeal Book Dept.: “Irish Rebellion of 1916 or Unbroken Tradition” by Nora Connolly

The Irish Rebellion of 1916

-Or The Unbroken Tradition

-by Nora Connolly

Boni and Liveright New York, 1919

https://books.google.com/books?id=G2umZxhfRhMC

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011718255

https://archive.org/details/irishrebellionof00obri/page/n5

Tag: Nora Connolly

https://weneverforget.org/tag/nora-connolly/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nora Connolly O’Brien 1965.

The Unbroken Tradition: The Irish Rebellion of 1916

-by Nora Connolly

James Connolly ICA Last Statement Reading

The Wolfe Tones Poem and Song for James Connolly