———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday September 9, 1919

I. W. W.’s Languish in Kansas Hell Holes, Part II of Series by W. D. Lane

From The Survey of September 6, 1919:

—–

—–[Part II of VI.]

II

To begin with the Shawnee county jail at the state capital of Kansas, Topeka. Ten members of the I. W. W. were confined there at the time of my visit. These were held under what has come to be known as the Wichita indictment. Their original arrest had occurred in November, 1917, so that they had been continuously confined in one jail or another for a year and two months. All of this time they were awaiting trial.

The Shawnee jail is a typical county lock-up in structure. Its outer walls are of brick. Men are confined in a sort of room within a room, formed by constructing a rectangular stockade inside the brick walls. The walls of this stockade are of steel lattice work, the bars of the lattice being about two inches wide and the holes about two inches square. It is through these holes that light and air enter. The cells are built in two facing rows inside the stockade. Their rear walls are the walls of the stockade itself and they open toward its center. In length the stockade is about thirty-five feet, in width twenty-six.

There are five cells in each row. Each cell is seven feet wide, seven feet long and seven feet high. Ordinarily two men are placed in each of these, but when the jail is crowded additional bunks are slung from the sides and four men sleep in this space. The central part of the stockade, that not occupied by cells, is thirty-five feet long and twelve feet wide. This is the prisoners’ livingroom, the only area besides their cells to which they have access. Light enters the jail proper through windows in the outer brick walls. These windows are frosted. The light must, therefore, pass through these frosted windows, through the steel lattice work and travel the length of the cells before it reaches this inner space. The result is that no daylight ever reaches this part of the stockade. The sun was shining brightly on the day of my visit, but its rays did not penetrate to this central area. A single electric bulb burned in the ceiling and shed a ghostly glimmer over the faces of the men; this bulb is kept lighted day and night. It was possible to read in only three of the cells and then only by standing close to the latticework. On cloudy days the men light candles.

The whole arrangement of the stockade, cells opening inward and dimly lighted central area, is so suggestive of a device for confining wild animals that the prisoners call this part of the jail the “bull pen.” The stockade itself is called the tank.

The floor of the bull pen is of sheet metal. The ceiling is of the same material. In hot weather the place boils. More over, the slightest contact between a hard object and the metal floor resounds throughout the stockade. When a dozen men walk up and down, as they did during my visit, their heavy shoes clanking at every step, the noise is nerve-racking. A prisoner dropped a tincup while I was there and the man to whom I was talking jumped as if he had been struck. He quickly gained control of himself and explained that it was the clatter. “The incessant noise of this place,” he said, “long since got my nerves. We’re all of us on edge. Having Caffray in the cell over there doesn’t help much.” Caffray was a member of the I. W. W. who was thought to be insane.

Only eight of the ten cells are used for prisoners. One of the remaining two has a toilet seat and wash bowl in it, the other a bathtub. During the day the men have free access to the toilet. At nine o’clock in the evening they are locked in their cells and remain there till seven in the morning. For their needs in those ten hours each cell is provided with a Karo corn syrup can, gallon size, its edges sharp and jagged.

The cans are filthy beyond description, being inherited from former occupants of the cell.

I noticed a peculiar-looking instrument, somewhat like the spray used to protect fruit trees from insects, and asked what this was. It was the “gun,” I was told, with which prisoners fight bugs and other vermin; its use is a regular part of jail life. This gun shoots a sort of creosote compound, which is supposed to act as a disinfectant. “There are bugs in here,” said Barr, the member of the I. W. W. who showed me around, “that Darwin and Haeckel never heard of. They are so thick that sometimes we are kept busy brushing them off at night.”

The men receive only two meals a day, one at eight o’clock in the morning, the other at two in the afternoon. For eighteen hours, therefore, they go without food. In view of their continuous idleness this would not be harmful, perhaps, if the food were nutritious and well cooked. In fact, it is neither. The food most frequently supplied is pork and beans. This is not healthful, at best, for men who are having no physical exercise; in the half-cooked condition in which they receive it, it is downright deleterious. Coffee, which is never accompanied by milk or sugar, is served only for breakfast. It is so weak that the men prefer to make their own, buying what they need on the outside when they have money for this purpose. I saw them make coffee, a fire of newspapers in one of their cells supplying the heat. The smudge from this added to the general heaviness of the atmosphere. Frequently, they complained, they are hard put to it to find enough paper for their fires.

The two o’clock meal was served during my visit. Promptly on the hour a big iron door connecting the prisoners’ part of the jail with the keepers’ part swung open and Hickson, the jailer, entered. Through a six-inch hole in the steel lattice work he passed pans of pork and beans, each prisoner receiving, in addition to one of these, enough bread to make five slices, each an inch thick. The men took their pans and sought various corners in the bull pen and cells in which to eat. The Kansas law directs every sheriff to seat his prisoners “at a clean table” and feed them “in suitable, proper dishes.” “Desperate characters” are excepted; they may be fed in their cells. Evidently every man in this jail was a desperate character, for there was no table and the only dish was the pan containing the pork and beans.

The quality of the food is not surprising when one learns the method by which provision for prisoners is made. Each county pays its sheriff, in addition to a salary and certain other items, fifty cents a day for every county prisoner in his jail; this is statutory. The United States follows this practice and pays the sheriff a similar amount for every federal prisoner lodged with him. The state supreme court has declared that this sum need be spent only for food. What the sheriff does not actually expend, he is legally permitted to put in his pocket; this is one of the perquisites of his office. He is not required to make a statement to anybody in regard to the amount he actually spends; each month he simply presents his bill to the county for so many prisoner-days, and the county pays with out asking any questions. If the sheriff is humane he will not believe in making money out of the stomachs of his prisoners; if not, he will spend as little as he can without creating a scandal and will keep the rest.

All office-holders in these counties know that the sheriffs do make something out of the money paid to them for prisoners’ food. An auditor of one county told me that the average amount saved by them was probably about $200 a year. Inasmuch as he was the brother of the sheriff of that county, and was talking to a complete stranger, his statement may be taken for what it is worth. A sheriff of another county quite frankly admitted to me that fifty cents a day for each prisoner was not enough to enable him to save what he thought he was entitled to save, and so he made an arrangement with the county commissioners to pay him seventy-five instead of fifty cents. This was entirely illegal, a fact which he made no effort to conceal. He stood ready, he said, to refund the surplus paid him in this way if any question concerning the transaction should ever be raised, a possibility that he thought extremely unlikely. The wife of one sheriff told me that she tried to make enough out of the prisoners’ food money to set her own table. Since her household comprised three or four people continuously, and more than that for parts of the year, the estimate of $200 was obviously too low in her case.

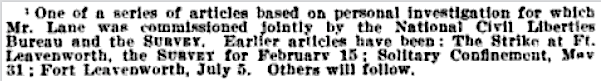

Fortunately, the I. W. W. has shown more concern for the welfare of its imprisoned members than has the government of United States. This organization sent to every one of the men in Kansas jails $1.50 a week for extra food and other necessaries. Accounts telling how this money had been spent were shown me in several of the jails I visited. In one an order had gone out that day for two loaves of bread, a quarter a pound of butter, raw hamburger, pickles, milk, matches, a package of Bull Durham smoking tobacco (smoking, prohibited in the jail, was indulged in nevertheless), and four Durham Duplex razor blades. The cost of the whole was $1.42. In another jail five members of the I. W. W. had spent the following amounts on food by periods:

Five other I. W. W.’s in the same jail had spent similar amounts. That the men were free to spend this money with the knowledge of the sheriff might perhaps be taken as evidence of a humane spirit in the administration, were it not for the fact that their doing so was directly to his advantage, enabling him to keep a larger share of the government’s allowance than he otherwise could have done.

One of the worst things at the Shawnee county jail was the attitude of the jailer and his deputy. In the course of a conversation with these men, before I had seen any of the prisoners themselves, I asked what treatment was given to men who became stubborn or refuse to obey the rules. McCall, the deputy, answered, “We go in and knock the guts out of those fellows.”

The talk drifted to other prisons. Warden Codding, of the Kansas state penitentiary, known for a rough and ready in-humanitarianism in his treatment of prisoners, was regarded by the jailer as much too lenient.

“Why, it used to be,” said Hickson, “that when I visited at prison the men would stand right up like statues”-the speaker imitated a statue, his hand in salute at his head—”until you passed by, but now they holler right out ‘Hello, ere’ and act loose-like, just like a bunch of men on a prairie. Coddling ain’t got no discipline. You’ve got to have discipline among prisoners, I tell you. The good prisoner, the fellow who wants to serve his term and get out, is benefited by discipline. It’s the rowdy bunch that wants to run the prison themselves that ain’t got no use for it.”

Hickson had heard of Sheriff Sprout, of Hutchinson, who, during the time that federal prisoners were lodged in his jail, treated them with refreshing humaneness. One prisoner developed symptoms of tuberculosis, and Sprout allowed him to leave the jail for a few hours each day so as to get some fresh air; later he permitted all the federal prisoners to leave their cells and sit under the big trees in the yard outside the jail. “These men helped to keep the jail clean, mowed the lawn, assisted Mrs. Sprout in the kitchen, cared for the chickens and even helped the sheriff in his duties as member of a local draft board. “I am not here to punish,” said Mr. Sprout, “I am elected as sheriff of this county to hold men for trial. A man may be innocent of the charges against him. If I turn him over to the court when the court is ready for him, I have done my duty. I believe in treating every man as a man and when I am convinced that a man can be trusted, I give him the freedom of the grounds.”

Mr. Hickson had no patience with such weakness as this. “The boys,” he said, meaning the I. W. W.’s, “owned the jail over at Hutchinson. Why, one of our deputy marshals went over there and found them with the run of the town. They even had the sheriff’s keys and went anywhere they wanted to. Sprout was buffaloed. The jail belonged to them I. W. W.”

The deputy then mentioned the “dungeon.” I had heard of this and asked if they ever used it.

“You bet we do,” McCall answered. “If a man tries to run this jail, we clap him in there and be generally comes round after two or three hours.”

Thinking that I would like to see a dungeon in which two or three hours would be enough to bring a man around, I tried to find it later, alone. Descending a stairway leading underground, I passed through a boiler room and coal cellar into a sub-basement with low ceiling and stone floor. Though this seemed an excellent place for a “dungeon,” I could find no trace of one. Returning to the ofiice I asked Hickson if he would show me the dungeon. He led me down the same stairs, into the same low-ceilinged, underground room that I had just left. Stepping up to what looked like a blank stone wall, he opened a steel door of the same color as the stone. For a moment my eyes told me nothing, since I was gazing into pitch blackness. Then I stepped forward, and by the aid of Mr. Hickson’s pocket flashlight, found myself inside a solid stone vault. The vault was six feet square and ten or eleven feet high. I looked for an opening or hole of some sort in the walls to let in light or air, but found none. There was absolutely nothing in the vault. The door was closed upon me and I stood as if in a tomb, sealed against the world outside. I shouted.

“Did you hear me shout?” I asked, as the door was opened.

“No,” said Hickson, and then continued: “We put ’em in here when they get troublesome. It’s pitch dark when the door is shut, you bet. No air, no light, no anything.”

“Not even a blanket to lie on?” I ventured.

“No, not even a blanket to lie on. They can lie on the floor. It don’t take much of this to bring ’em around, I can tell you.”

Perhaps the worst effect of months of confinement in the Shawnee county jail, as in others, was the continuous idleness. Human beings can stand much when they have work to do. For a year and a half these men had been idle in body and brain. An occasional book or magazine, sent by friends, comprised their total diversion. They spent their days in crawling from cell to bull pen and from bull pen back to cell—seeing always the same ghastly faces in the glimmer of the electric light, hearing always the same voices, and smelling always the same smells. Their muscles, once strong, grew flabby and their minds, once alert, grew dead. “For five months,” said a prisoner, who had been released from another jail-on bond, “there were eight of us on the upper ‘government’ tier. These were the only faces I would see all day long. Two were released, leaving only six. It got so I didn’t want to see any of ’em. When a man came up to you, you would tell by the look on his face what he was going to say. We knew each other by heart. There we were, the best of friends, undergoing the same hardships and suffering from the same cause, yet we actually came to hate each other!” What a mockery, I thought, were those words in the Kansas law which declare that “all prisoners shall be treated with humanity and in a manner calculated to promote their reformation.”

Before leaving this jail, I asked to see Jack Caffray. Caffray was a member of the I. W. W. who, in the opinion of several people who had seen him, was mentally unbalanced. He had contracted syphilis, it was said, in the Spanish-American war and the disease was now supposed to be in an advanced stage. He wrote incessantly in jail, scribbling on all sorts of bits of paper, and tearing up nearly everything that he wrote. He had a mania, too, for possessing ink, sometimes accumulating seven or eight bottles in his cell. During the night he would get up repeatedly, pace back and forth, mutter to himself and rush out to the toilet whenever the door was left open, as it was occasionally because of his condition. His writings took the form of poetry and of innumerable letters to people he had never seen. With numerous grins, winks and nods of the head he asked me to mail a letter to a woman in a nearby town with whom he wanted me to intercede in his behalf. His friends said that he had never seen this woman, yet he wrote to her continuously.

In answer to my request, Caffray’s face appeared at the hole through which I was talking to the prisoners.

“Are you Jack Caffray?” I asked.

“Mr. Jack Caffray,” he answered.

“Why do you insist on the Mr.?” I asked.

“Well, you can put the little E-s-q on the end, if you prefer.”I pointed to the pen in his hand and asked him what he did with his writings. His only reply was a hollow laugh, then an attempt at denial. I tried further to draw him out. He described the bugs and the unsanitary toilets in the jail. He mentioned his syphilis and said that the medicines the government doctor gave seemed to do little good. At last he mentioned the Spanish influenza.

“Have you had the ‘flu?’” I asked.

“Most certainly,” he answered.

“Have any of the others had it?”

“Certainly.”

“How did they get it?” I asked.He looked at me long and hard. Breaking into his hollow laugh, he said, “Why Mr. Lane, you know how they got it as well as I do.”

“Well,” I ventured, “there are various ways of getting it, aren’t there?”

“There are scientific names for how you get it,” he said, “but I’ve seen too much of it. I’ve seen the boys over in the Newton jail get it and I’ve seen those in the Wichita jail get it and I’ve seen ’em get it here. Yes, and I’ve seen people with what they call spinal meningitis, and the doctors gave some fancy description for how they got it. They tell you the flu is due to atmospheric conditions”-his voice was now raised to a shout—”but what I want to know is: Who put it in the atmosphere? I’m not mentioning any names but I see in your face that you know as well as I do how it got there. The flu and meningitis and other diseases are all put there by somebody. Who? Mind, I’m not mentioning any names, but I know who put it there.”

He paused for breath. Then he shot at me:

“The exploiters! That’s who. I’m not mentioning any names, but you know as well as I do that the exploiters put these diseases there. Maybe they shoot ’em under our beds at night. Maybe they put ’em in our food. I don’t know how they do it. It’s part of the class war. It’s scientific extermination, that’s what it is”—his voice was now ringing throughout the jail, his face twitching—“They know what they’re about. The people who think we workers are a contemptible, despicable lot, who want to exterminate us, that’s who put the flu and meningitis into us. Oh, it’s scientific extermination with a vengeance.” He ended with a sweep of his arm and his hollow, meaningless laugh.

Caffray was receiving very poor medical attention, if any. For weeks the jail physician did not know that he had syphilis. When Caroline Lowe, an attorney for the I. W. W., told the doctor this and asked whether treatment by a specialist was not desirable, he replied: “Oh, that will be all right, Miss Lowe. Nothing serious about that. I can cure that damn easy. All Caffray will have to do will be to take the medicines I’ll give him tomorrow and he will be cured right up.”

I charge that Jack Caffray, at the time of my visit, was either insane or manifested such strong evidence of insanity that an examination by an alienist should have been held at once.

I charge that no such examination was ever held and that the doctor who attended Cafiray did not know that Caffray was supposed to be either insane or syphilitic until his attention was called to this by a third person.

I charge that the authorities of the Shawnee county jail, and through them the United States government, kept Caffray confined, like any other prisoner, in a small tank with twelve men where the conditions of life were such as to prey upon even the strongest minds.

I charge that the continued presence of Caffray among these other men was not only bad for him but was a menace to the health and sanity of them all.

I charge that the officials who permitted this condition to exist were either criminally negligent or inhumanly callous and ought to be removed from their positions forthwith.

Months in the same cell with Jack Caffray, in another jail, had had their effect upon another prisoner. Small wonder that the mind of Stephen Shuren snapped one day when he heard that the trial of the I. W. W. had been delayed and that he would have to spend another winter in jail. With the razor with which he was shaving he cut a deep wound in his neck from ear to ear, and fell to the floor, senseless. When they reached him they thought he was dead. He moved while on the stretcher, however, and under the direction of Miss Lowe, who happened to be in the jail at the time, he was rushed to the best hospital in town. At first he didn’t want to get well. “Why should I live?” he wrote on a piece of paper while still too weak to talk: “life has denied me everything. What have I to live for?” In the end. however, he recovered. Two weeks later he was back in jail; but the long confinement had told upon his mind and he remained moody and despondent. His friends in jail kept guard over him, day and night, in two-hour shifts, for weeks after that. They tried to interest the marshal in Shuren’s condition, but the marshal hdd other business. When I saw Shuren in this other jail, three and a half months after his attempt to commit suicide, the expression in his eyes was not normal and he looked at me from out a clouded face. The men said that little of his mind seemed to remain. One of them always shaved him now, and this man told me that often, as the razor moved this way and that about Shuren’s face, he would follow it with his eyes, evidently hoping that the hand that held it might slip—or perhaps intending to seize it himself and inflict the gash that would put an end to his misery.

———-

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Ralph Chaplin, When we claim our Mother Earth, Leaves 1917

https://archive.org/stream/whenleavescomeou00chapiala#page/4/mode/2up

The Survey, Volume 42

(New York, New York)

-Apr-Sept 1919

Survey Associates, 1919

https://books.google.com/books?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ

Survey of Sept 6, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA787&pg=GBS.PA787

“Uncle Sam: Jailer” by Winthrop D. Lane, Part II

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA806&pg=GBS.PA806

See also:

Tag: Wichita IWW Class War Prisoners

https://weneverforget.org/tag/wichita-iww-class-war-prisoners/

American Political Prisoners

Prosecutions Under the Espionage and Sedition Acts

-by Stephen Martin Kohn

Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994

(search separately: “jack caffray”; “albert barr”; “stephen shuren”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=-_xHbn9dtaAC

Tag: Caroline A Lowe

https://weneverforget.org/tag/caroline-a-lowe/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Commonwealth of Toil – Joe Glazer

Lyrics by Ralph Chaplin