———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday September 10, 1919

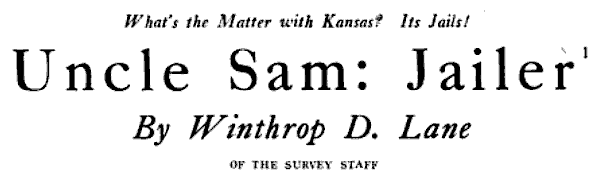

I. W. W.’s Languish in Kansas Hell Holes, Part III & IV of Series by W. D. Lane

From The Survey of September 6, 1919:

—–

—–[Parts III & IV of VI.]

III

Another jail chosen by the United States for the confinement of its prisoners awaiting trial is the Wyandotte county jail at Kansas City, Kan. I shall not go into detail about this. As at Topeka, the men are kept in an inside stockade or “tank;” this has fourteen or sixteen cells and a somewhat larger bull pen than the other. The pen is artificially lighted. Little attention is paid to ventilation. Although there were upwards of thirty men in the jail at the time of my visit, only one of the thirty-six windows was opened wide and another was opened about two inches. The men complained bitterly of the cold nights, a complaint that I could readily understand when I saw what was provided them for covering. For two nights I had been cold underneath three thicknesses of blanket and a spread, and on one of these nights had got up and placed my overcoat over me. Yet these men had a single blanket apiece, which they could fold at most into two thicknesses.

The toilets, located in an end cell, were dirty and had broken seats. The men ate their meals in their cells, after wards washing their own pans and dishes. The only places where they could wash these were in the bathtub or in the tub in which they washed their clothes. The smell of garbage was almost constantly in their nostrils, since the can for the refuse from their meals was kept inside the tank and was emptied only two or three times a week. It was full when I saw it and gave off a strong odor.

As at Topeka, the men are fed twice a day and, as at Topeka, the members of the I. W. W. supplemented what the government gave them with food purchased on the outside. There is an “upper tier” to the tank in this jail, formed by placing cots on the roof of the lower tier. This is a much more desirable place to live than the tank itself, since the air is better and there is plenty of daylight. At the time of my visit twelve prisoners were occupying these cots, with ample room for fifteen or twenty more. I asked the jailer why twenty-one men were closely confined in dark, ill-smelling quarters below when there was so much unoccupied space above. He said that the men down below did’nt “deserve” to be up there. I inquired what he meant by “deserve,” remembering that some of those below were merely awaiting trial.

“Well, now,” he said, “suppose you was arrested, Mr. Lane, and brought in here—maybe for being drunk. Say you had them good clothes on and we seen you was a gentleman and not used to hard conditions, you’d deserve to be put up here where it’s a little nicer, wouldn’t you? But some of those fellows down below ain’t got it coming to them. They don’t appreciate things like that.”

One of the I. W. W. members told me to be sure to see the juvenile department of this jail, although, he said, there were no children in it at present. At my first request the matron was loath to permit me to see it but finally consented, turning the keys over to her husband, the jailer. We unlocked a heavy steel-latticed door at the foot of a flight of stairs and ascended to a room at the top. This was dimly lighted and had no furniture of any sort. What was my surprise, in view of what I had been told, to stumble over the legs of a lad eight or nine years old, who was sitting on the floor. This was the signal for five others to troop out from the corners and dark places into which they had retreated when they heard our steps. All of these six children had been arrested that morning. They ranged in age from six or seven to fourteen. During my brief visit they talked and scuffled and took their lot quite nonchalantly. One of them said that he had broken into a saloon the night before and been caught. The jailer explained that children of that age were often confined in the jail for two weeks at a time while their cases were being disposed of.

Two cells opened off this room; in these the boys were to sleep. Beds were slung from the sides of the wall, as in the cells below for men, and the bedding was dirty and unaired. It was apparently in the same condition in which the children last there had left it. The toilet was dirty and broken.

The lads followed us downstairs, when we descended, to the latticed door at the foot. Here they could watch the life of the jail going on and could talk to adult prisoners who were allowed outside the tank. The parents of one of the boys had arrived while we were upstairs and were now asking to see their son. I stood aside to see what happened. The boy was allowed to come to the bottom stair, inside the latticed door, and the parents, both of whom were crying, were allowed to approach this door from the other side. They had to content themselves with looking at their son through this heavy grating and with talking to him in the presence of eight other people. They could not touch him or speak a word that would not be heard.

Drawing Bagley, the jailer, off to one side, I asked if parents were never allowed greater privacy with their children than that, “Well, it’s good enough for ’em, ain’t it?” he answered. I suggested that the parents’ feelings might be relieved, and the boy himself benefited, if they could talk to him alone or put their hands on his head. “Why,” said Bagley, “if we allowed that, we’d have a regular community house here. People’ld bring their beds and spend the night with us. You have to have rules, don’t you?”

IV

My effort to secure entrance into the Sedgwick county jail at Wichita was blocked at the outset by the authority of the deputy United States marshal, Sam Hill. Mr. Hill’s conversation, like his name. is chiefly expletive. He wanted to know, first, whether I was a member of the I. W. W.; next, whether I was an attorney; third, where I lived, and finally why I had come and what I proposed to do with the information I gathered. My answers to these questions he took lightly, asking whether I could prove that they were true. A New York city police pass, a card showing that I had registered under the selective service act and another showing the class to which I had been assigned, were all produced, as at least establishing my identity. “Hm,” said Mr. Hill, after scanning them closely, “I see you have a lot of cards with you.”

Mr. Hill turned me over to B. F. Alford, the agent of the Department of Justice in Wichita. Mr. Alford, however, refused to make so weighty a decision as my case seemed to present and sent me back to Mr. Hill. This time I cited, for the benefit of the deputy marshal, the Kansas law, which provides that friends who desire to exert a moral influence over prisoners may visit them at all reasonable times. This drew from Mr. Hill the following:

“You needn’t think, young feller, you can come here from New York and bluff me. And you don’t have to tell me what the Kansas law is, either. I know the law as well as you do. I’m United States marshal and I don’t give a damn for the Kansas law. I don’t have to let you in that jail if I don’t want to, and I can telegraph to the United States district attorney in Kansas City and keep you sitting there on your -—- all week, if I want to, can’t I? Yes, you bet I can. To hell with your coming here from New York and telling me my business. To hell with the Kansas law. I can’t be bluffed by any smart Alecks, see.

We parleyed a little longer and presently it became evident that Mr. Hill, finding, perhaps, that my patience was not easily exhausted, was changing his tactics and would let me in. His final instructions were that I could go to the jail, and could see Anderson (the member of the I. W. W. whose name I had used); but that I could see no one else.

Apparently Mr. Hill’s telephoned instructions to the jailer were not explicit, for no sooner had I arrived at the jail than Anderson, called to the door, escorted me upstairs to the “government tier,” where I was immediately surrounded by all ten of the I. W. W. members then confined there. I remained in the jail for several hours.

The Sedgwick county jail is the worst place for incarcerating human beings that I have ever been in. Built forty years ago, it has undergone additions from time to time, so that today it is not the compact structure that many jails are but has many wings and cages. There are cells for approximately 100 prisoners. It is filthy with the accumulated filth of decades. No longer would it be possible to give the jail a decent cleaning. The metal floors are periodically “laraped” with black jack, a greasy substance the chief effect of which is to fill the corners with a coagulated mass of dust and floor sweepings, hardened by the glue-like action of the black-jack. The toilets throughout are covered with dirt. Many of them are encrusted with excreta and a few actually stink. The men declare that they do not dare to sit down on them, because of the vermin.

The age of the jail has produced crevices and openings in the brick walls through which rain and, in winter, melting snow pour in. Water-marks in several places on the walls attest this; last January a small flood from this cause was so serious as to be reported in the local press. Rats issue through these holes and through the crevices in the steel flooring. At evening, when the prisoners have quieted down, these rats come forth in great numbers. It is not uncommon for a prisoner to be awakened by a rat running over his bed or even across his face.

The prisoners have various methods of combating the rats. One is to hang loops of greased string from the base of the steel lattice work and cell doors. These loops dangle about an inch from the ground and are so constructed that when the head of a rat enters the loop, the string tightens and the rat is caught. Six rats constitute a good night’s catch by this device. Another method is to attach a short hose to the steam pipe of a radiator, to insert the other end of the hose through a crack in the floor and to “steam” the rats out, killing them as they issue forth. One prisoner made an elaborate trap out of a small wooden box, using bread for bait, and caught two large rats alive by this method. The prisoners say that a former night jailer used to go down into the basement at night and shoot rats with a small target rifle for practice. Many so hit crawled under the flooring and died, but the prisoners were not allowed to remove their dead bodies.

The food had been very poor just before my visit, but a change in the sheriff had brought about a slight improvement. The new jailer, too, served food in new granite pans instead of the rusty tin ones used before. The men were spending most of their allowance from the I. W. W. organization for food, the amounts cited on page 808 referring to this jail.

The organization was also supplying money for other purposes. Nearly all of the men complained of trouble with their teeth. A local dentist had fitted one of them with a set of false teeth and had done elaborate bridge-work for a second. For this they had paid him $88.50. When I asked the dentist whether the government, in whose care these men had been for over a year, had not met a part of this expense, he replied: “The government would not pay for dental treatment unless the men were actually in pain.” An osteopath had given chiropractic treatment to two of their number, one of these being Shuren. This had cost $2 a treatment, or $48 in all. In taking care of four of their number, therefore, they had thus expended a total of $136.50.

Most of the conditions that I have so far described are the product of ignorance and callousness. The men responsible for them, and the communities that permit them, are for the most part simply bereft of any understanding of what it is that they are doing. There remains to be described a device for confining men that exhibits both ingenuity and perverted purpose. It combines the efficiency of modern invention with the insensibility of the thirteenth century. Yet it is defended by people who are no doubt quite humane in their private lives.

This is the revolving cage or “rotary tank,” as the prisoners call it, in the Sedgwick county jail. The reader can form a mental picture of this cage by imagining an ordinary cylindrical bird-cage, revolving about a vertical rod down its center. Imagine, further, the bird cage divided into upper and lower halves. Each half is cut vertically into segments, V shaped. The wide part of the segment is at the circumference and the small part at the axis. The cells are these V-shaped compartments. Placed in a row, they would look like this: VVVVVVV. Actually, of course, they are in a circle, with the points of the v’s coming together at the axis.

There are ten cells in each tier. The mouth of the cell is not entirely open. Instead, a series of metal plates partly enclose the cage, so arranged that only about half of each cell mouth is open.

The cage revolves inside a stationary steel lattice frame. This frame is two or three inches from the tank; it forms, therefore, a wall around the entire contrivance. There are two doors in this wall, one on each tier. The cage is made of heavy metal; the floors, roof and plates are solid metal sheets. In weight the cage is said to be thirty or thirty-five tons. Each cell is eight feet six inches long and six or seven feet high; at the mouth it is six feet six inches wide, tapering to twenty-two inches. The open portion of each mouth is three feet four inches wide.

This cage was the wonder of the county when it was built. Regarded as proof against escape, it seems to have justified that hope, for I learned of no escapes from it. Originally it revolved by water power. At that time it was kept in motion day and night; a slow, continuous revolution gave the men inside no rest. Incidentally it prevented them from working through the steel frame outside the cage, for they were never in one place long enough to make any headway.

The machinery for keeping it in motion broke down or the water power dried up. Today the tank is operated by levers, which in turn are worked by human hands. Prisoners in the cage are allowed to come out once a week for a bath. To bring them out, the cage is revolved so that the mouth of each cell, in turn, comes opposite the door in the steel frame. The occupant then steps out upon a platform the other side of the steel frame.

This is the ostensible method of bringing them out. Actually a labor-saving element is introduced. To bring the cage to a stop for each prisoner would obviously require nine or ten startings and stoppings of the cage. Its great weight makes this an arduous task. The method used, therefore, is to give notice that the tank is to be revolved, which enables each prisoner to be in readiness at the mouth of his cell, and then to turn the cage in one continuous revolution; each man, as his cell comes opposite the door in the steel frame, jumps upon the platform and quickly makes way for the man in the next cell, who is right at his heels. He must make his exit not only through the three feet four inches of space in the mouth of his cell, but also through the door of the steel frame, which is of about the same width. A tardy jump or a misstep might be serious.

Another source of danger lies in the fact that there is nothing between the prisoner standing at the mouth of his cell and the stationary steel frame outside. If a hand or a leg should get caught in the frame while the tank is in motion, an injury would be almost sure to result. One prisoner showed me a scar on his ankle, which he said was left from the time, some months before, when he caught his foot in the frame in this fashion.

The cells in the cage are poorly lighted, only those in a favorable position with regard to the windows receiving enough light to read by. In the others it is so dark that I had to use matches to examine them closely. Each cell has a bed, slung to the wall in such a way that it can be raised and lowered at convenience. An open toilet at the small end gives off a noticeable odor. As I drew near one of these toilets and bent down to look at it, the smell of excreta was so strong that I drew back involuntarily; in the trough, underneath the seat, excreta were plainly visible. The flushing apparatus, I was told, was frequently out of order. This toilet is the constant companion, day and night, of the man confined in the cell. Ventilation, owing to the peculiar construction of the cage, is almost out of the question.

Fourteen members of the I. W. W. spent fifty consecutive days in this cage, according to statements of their own number. This is denied by the jail authorities, who admit, however, that three or four of the “ringleaders” among the I. W. W. prisoners were confined in it for several days. Whether the statement of the I. W. VV.’s is true or not is not of much concern, since the cage has been regularly used for confining prisoners.

Last January the beds were removed from the cage and announcement was made that prisoners would no longer be confined there. This was the effect of an order by Judge Richard E. Bird, district judge of Wichita. The I. W. VV.’s themselves were in no small part responsible for the discontinuance. This came about through state rather than federal intervention. Descriptions of the cage sent out by I. W. W.’s aroused inquiries from many people, among these the National Civil Liberties Bureau, which sent its inquiries to the Department of Justice. On December 3 last, one of the assistant attorney generals, Mr. Ginham, wrote to the bureau, saying that an investigation of the jail had been made and “it is not believed that the situation is such as to call for any further action on the part of this department.” Seven days later another assistant attorney general, W. L. Frierson, wrote that, although the jail was not an “up-to-date institution,” yet it was “in fairly good sanitary condition.” Little was to be expected, apparently, from the federal government. Meanwhile protests had reached Arthur Capper, then governor of Kansas. Governor Capper asked Judge Bird to make an investigation and a month later came the order for its discontinuance. Whether the discontinuance will be permanent, or whether the cage will again be resorted to after public interest has died down or under the stress of overcrowding, remains to be seen.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Ralph Chaplin, When we claim our Mother Earth, Leaves 1917

https://archive.org/stream/whenleavescomeou00chapiala#page/4/mode/2up

The Survey, Volume 42

(New York, New York)

-Apr-Sept 1919

Survey Associates, 1919

https://books.google.com/books?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ

Survey of Sept 6, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA787&pg=GBS.PA787

“Uncle Sam: Jailer” by Winthrop D. Lane, Part I

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA787&pg=GBS.PA806

Parts III & IV

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xmc6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA787&pg=GBS.PA810

See also:

Tag: Wichita IWW Class War Prisoners

https://weneverforget.org/tag/wichita-iww-class-war-prisoners/

American Political Prisoners

Prosecutions Under the Espionage and Sedition Acts

-by Stephen Martin Kohn

Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994

(search separately: “the trial in wichita”; “c w anderson”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=-_xHbn9dtaAC

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Commonwealth of Toil – Gerd Semmer

Lyrics by Ralph Chaplin