—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday August 21, 1902

Mother Jones News Round-Up for July 1902, Part V

Judge Jackson Proves Himself a Coward, Afraid to Sentence Mother Jones

From the Duluth Labor World of July 26, 1902:

IT IS AN OUTRAGE

———-ORGANIZERS OF MINE WORKERS

IN PRISON FOR CONTEMPT.

———-

Judge Jackson, of United States Circuit Court, Passes Sentence

-Fears to Sentence “Mother” Jones

-President Mitchell Says Decision “Imperils the

Rights of All Americans in the Courts.”

Judge Jackson, of the United States Circuit Court, at Parkersburg, W. Va., has held “Mother” Jones and seven other organizers and officials of the United Mine workers guilty of contempt of court in violating his injunction of June 19, prohibiting them from “making inflammatory speeches,” and has imposed a sentence of from thirty to ninety days upon all, with the exception of “Mother” Jones.

The injunction in question, which Judge Jackson issued, is directed at the right of free speech. It is a deadlier blow at American liberty and the rights of the masses of the people than has been struck for a long time. It is an outrage which cannot but make the blood of every working man boil with indignation.

Trade unionists know President John Mitchell, of the United Mine workers. They know him by reputation all over the land. They know that he has compelled even those on the capitalistic side to acknowledge that he is cool-headed, conservative, brainy and far-seeing. He is not given to loud talk or extravagant assertions. Yet President Mitchell says of the Jackson decision:

“It imperils the rights of all Americans in the courts.”

It takes something of more than ordinary significance to draw from President Mitchell such an accusation against one of the highest tribunals of justice in the United States. Even now the statement is dignified, and quiet, but for that very reason it carries all the more force with thinking men.

“The rights of all Americans in the courts” is imperiled by what? Trades unions? Strikes? Organized, labor? Boycotts? Oh, no! By the action of a man chosen to meet out justice from the bench of the United States Circuit court, which is next to the Supreme court itself the highest court of justice in the country.

In the case of “Mother” Jones, the judge suspended contempt. In doing so he said that she had been found guilty of contempt, “but as she was posing as a martyr, he would not send her to jail or allow her to force her way into jail.” No more insulting message to organized labor could have been given out than that comment on the case of “Mother” Jones, coming after his action on her case. If she were guilty, she deserved punishment just as much as the others. But, because, forsooth, she is well known among organized labor circles, and her imprisonment would call attention to the monstrous injustice of this ermined anarchist, he sneeringly remarks that he will not allow her to “pose as a martyr,” and turns her loose.

But, by the same token, if “Mother” Jones has any claim to pose as a martyr, so has every other individual imprisoned by this petty tyrant. And while they may be more obscure, they are none the less the representatives of the organized working class, and Judge Jackson may find that their imprisonment, under his infamous order, will be just as quickly and effectively resented, and will be remembered just as long by the working people as would the imprisonment of “Mother” Jones.

The truth is, this judge is a coward, a poltroon, who did not dare to carry out his own infamous decree. He lacked the courage to do his own dirty work, when he thought that it might arouse the working people of the entire country.

If anyone doubts that this usurper of power and enemy of the right of free speech is a dastardly coward, listen to this from the capitalistic press:

“It is currently reported that the house of Judge Jackson had been guarded for several nights, and that guards were in the court room.”

Yet this is the man who metes out justice. He fears that the common people, the workingmen, will respond to his anarchistic abuse of power with a resort in the same spirit to force. He judges others by himself. He fears the people. By the same sign, he feared to imprison “Mother” Jones, and his talk about “posing as a martyr” was the basest of hypocrisy, and the laboring people everywhere will recognize it as such.

Secretary W. B. Wilson, of the United Mine workers, is also to be arrested for violating the injunction, because he talked in violation of Judge Jackson’s order.

The case will be taken to the higher courts, and up to the Supreme court. Moreover, it will be laid before president Roosevelt, and he will be urged to intervene. It is quite safe to predict that President Roosevelt will “not see his way clear to interfere with the judicial branch of the government,” And there you are!

Habeas corpus proceedings have already been begun for the release of the imprisoned men, and it is hoped that they will be successful. But meanwhile they will be in jail, and all the restitution which can ever be made to them, if Judge Jackson is finally overruled by the Court of Appeals, can never wipe out the injustice under which they have suffered.

In rendering his opinion Judge Jackson gave this refreshing epitome of his opinion of labor organisations and their representatives:

While I recognize the right of all laborers to combine for the purpose of protecting all their lawful rights, I do not recognize the right of laborers to conspire together to compel employes, who are not dissatisfied with their work in the mines to lay down their picks and to quit their work without a just or proper reason therefor, merely to gratify a professional set of agitators, organizers and walking delegates, who roam all over the country as agents for some combination, who ate vampires that live and fatten on the honest labor of the miners of the country and who are busybodies, creating dissatisfaction among a body who do not want to be disturbed by the unceasing agitation of this class of people.

The right of a citizens to labor for wages that he is satisfied with is a right protected by law and is entitled to the same protection as free speech and should be better protected than the abuse of free speech in which the organizers and agitators indulge in trying to produce strikes.

He speaks as the representative of the class from which he comes; of the class to which lie owes his place; of the class which employs labor; of the class which disregards the laws intended to prevent the capitalist from taking the public by the throat and compelling them to give up their earnings. He has no real sympathy with the working class, nothing in common with them.

[Photograph added.]

From The Worker of July 27, 1902:

THE TRIAL OF MOTHER JONES.

—–

Federal District Attorney Declares Her

a Dangerous Woman.

—–Decision Not Yet Given as The Worker goes to Press–

Vigorous Effort to Imprison or Banish

Brave Woman from West Virginia.Tuesday, July 24, was the day set for Judge Jackson of the United State court at Parkersburg, W. Va., to give his decision in the cases of Mother Jones, Thos. Haggerty, and eleven other organizers of the United Mine Workers, under arrest for having violated an infamous injunction which forbids them to hold miners’ meetings anywhere within sight of the mine properties, to march on the public roads in the vicinity, or, as a correspondent of The Worker put it, to do anything except eat and drink-and the West Virginia miners don’t get a chance to eat too much, with or with-[out?] injunctions.

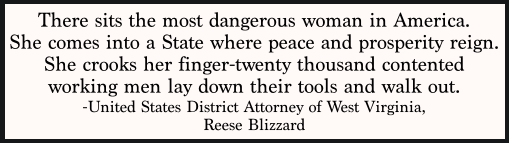

Reese Blizzard, United States District Attorney, conducted the prosecution. He is counted a very able lawyer and he used all his powers to carry his point-or, rather, to carry the point for the mine owners. His closing speech occupied four hours.

Cannot Understand Her.

Mother Jones is obviously considered the most dangerous offender. The “Operators” and their tools cannot understand this wonderful little woman, who is content to labor incessantly, to go hungry and cold sometimes, to endure all manner of hardships and insults and dangers, to go to prison, if need be, in order to carry on her work of organizing and educating and inspiring the miners, and whom the strongest men among the mine workers treat with such confidence and such perfect respect.

“A Dangerous Woman.”

The press reports say that Blizzard called attention to the fact that Mother Jones was especially dangerous owing to the fact that her influence among the miners is almost unlimited and that, also by reason of her powerful intellect she is an instrument of great harm. The miners, he said, are receiving good wages and their condition is satisfactory, but, according to the testimony of this woman, she has come into this state with the express intention of getting eight or nine thousand miners to throw down their tools and quit work that they may help the two or three hundred who were dissatisfied with their condition and had quit the service of their employers.

After dilating on the enormity of Mother Jones’ guilt, he closed by suggesting that if she would leave the state and promise never to return, the government would be satisfied for the present and would not insist on imprisoning her.

Mother Jones, of course, treated this exhibition of Southern chivalry and Rooseveltian strenuousness with the contempt it deserved. She is not the sort of woman to desert her post under fire.

Judge Tries to Entrap Her.

Judge Jackson himself, the trial justice, took a hand in the examination of Mother Jones and tried, by leading questions, to entrap her into an admission that she was an Anarchist, but he did not succeed very will.

When asked if she had not said that the operators were the same sort of people that had crucified Christ, the witness replied that she had made such a remark.

“Well,” questioned Judge Blizzard, “do you not think that the crucifixion of Christ was the worst crime ever committed?”

“No,” answered the witness in loud tones,

It was not nearly so bad as the crucifixion of little boys in the coal mines who are daily being robbed of their manhood and their intellect by what they are, through necessity, compelled to undergo. Christ could have saved himself, the boys cannot.

Even the flippant reporters of the capitalist papers, all whose sympathies seem to be with the “operators,” were evidently impressed with her courage and dignity.

As The Worker goes to press, the decision has not been rendered, and it is impossible to guess the outcome of the case.

From the Baltimore Sun of July 27, 1902:

There was an affecting scene at the home of Judge Jackson last night, when “Mother” Jones, who had just been convicted of contempt of court, went to visit him after he had released her without a jail sentence.

“Mother” Jones expressed her gratitude for his consideration and was then presented to Mrs. Jackson. “Mother” Jones had in some manner learned that Mrs. Jackson had pleaded with her husband with tears in her eyes not to send the white-haired woman to jail, and as soon as she was presented she threw both arms around the one who had successfully entreated in her behalf and kissed her affectionately. Her call lasted for over an hour.

From the Baltimore Sun of July 28, 1902:

FOR MINERS’ RELEASE

———-

Habeas Corpus Proceedings To Be Pushed With Vigor.INDIANAPOLIS, July 27.-At the mine workers’ national headquarters it was announced today that no time will be lost in pushing the habeas corpus proceedings for the release of members of the organization arrested under the edict of Judge John Jay Jackson, of the United States District Court, at Parkersburg, W. Va.

Secretary Wilson today explained another principle in the miners’ case, on which they will base their claim to be set free. According to Mr. Wilson, not one of the men arrested was proved to have made speeches, inflammatory or otherwise, after Judge Jackson’s restraining order was issued.

“The Injunction was issued on June 19,” said Mr. Wilson, “and the meeting complained of was held the next night. ‘Mother’ Jones was the only speaker, and none of the men arrested said a word publicly to the miners. The only thing proved against them was that they applauded the remarks of ‘Mother’ Jones. They were arrested the moment the meeting was over, so that they had no chance to speak if they had wanted to. I do not see how men can be committed to jail for such a trivial offense as this, and I believe the habeas corpus proceedings will set them free.”

No charges will be filed against Judge Jackson, Mr. Wilson says, until the habeas corpus suits shall have been decided……

From the Baltimore Sun of July 29, 1902:

MORE WARRANTS ARE OUT

———-

West Virginia Miners Charged With Contempt Of Court.CHARLESTON, W. Va., July 28.-Upon information made before Federal District Attorney Atkinson today warrants of arrest were issued for about 15 persons, charging them with contempt of court in violating the injunction issued by Judge Keller, covering the Flat Top coal field, along the Norfolk and Western Railroad. The clerk declined to give the names of those for whom warrants were Issued.

Federal Judge Keller today issued an injunction against G. W. Purcell, a member of the National Executive Committee of the United Mine-Workers; W. B. Wilson, national secretary; “Chris” Evans, national statistician; “Mother” Jones and five others, at the suit of the Gauley Mountain Coal Company. It is in the same form as those heretofore issued.

It was charged that Purcell, Evans, Wilson and the others were purchasing and distributing supplies to feed the strikers in this district.

Note: Emphasis added throughout.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote re Mother Jones, Most Dangerous Woman, Machinists Mly, Sept 1915

(search: “mother jones” dangerous)

https://google.com/books/reader?id=9e_NAAAAMAAJ

The Labor World

(Duluth, Minnesota)

-July 26, 1902

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1902-07-26/ed-1/seq-2/

The Worker

(New York, New York)

-An Organ of the Socialist Party [SPA]

(Known in New York State as

the Social Democratic Party.)

-July 27, 1902, page 1

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/020727-worker-v12n17.pdf

The Sun

(Baltimore, Maryland)

-July 27, 1902

https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/372442844/

-July 28, 1902

https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/372444415/

-July 29, 1902

https://www.newspapers.com/image/372444868

IMAGE

Mother Jones , Phl Inq p24, June 22, 1902

https://www.newspapers.com/image/168338244/

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: Whereabouts and Doings of Mother Jones for July 1902

Part I: Organizers for United Mine Workers Surrounded by Injunctions in West Virginia

Part II: Found in Court in West Virginia, Speaks at Miners’ Convention in Indianapolis

Part III: Found in Cincinnati on Her Way Back to West Virginia to Face Possible Jail Term

Part IV: Judge Jackson Severe on the Miners, Releases Mother Jones with Lecture

Tag: Mother Jones v Judge Jackson 1902

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mother-jones-v-judge-jackson-1902/

Tag: West Virginia Coalfield Strike of 1902-1903

https://weneverforget.org/tag/west-virginia-coalfield-strike-of-1902-1903/

Most Dangerous Woman in America

Hellraisers Journal for Oct 13, 1907

How Mother Jones Became Known as

“The Most Dangerous Woman in America”

Note: The trial of Mother Jones and the other UMW organizers took place before Judge Jackson, at Parkersburg WV, from June 24th to June 27th. Closing arguments were delivered on July 11th and July 12th. Judge Jackson imposed his sentence on July 24th. I believe it was during closing arguments (July 11 or 12) that Blizzard made his famous comment regarding Mother Jones, as it is after closing arguments that we begin to find mention of Mother as “dangerous.” More research needed.

Sept 30, 1902, Ottumwa (IA) Tri Weekly Courier

-Mother Jones re Prosecutor Blizzard: “Dangerous Woman”

(During speech Mother states that Blizzard called her a dangerous woman during his closing argument-which would have been July 11th/12th.)

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/108087187/sept-30-1902-ottumwa-ia-tri-weekly/

Mother Remembers Judge Jackson

From the Autobiography of Mother Jones

-“Chapter VI: War in West Virginia”

https://archive.iww.org/history/library/MotherJones/autobiography/6/

-“Chapter VII: A Human Judge

https://archive.iww.org/history/library/MotherJones/autobiography/7/

Chapter 6 – War in West Virginia

One night I went with an organizer named Scott to a mining town in the Fairmont district where the miners had asked me to hold a meeting. When we got off the car I asked Scott where I was to speak and he pointed to a frame building. We walked in. There were lighted candles on an altar. I looked around in the dim light. We were in a church and the benches were filled with miners.

Outside the railing of the altar was a table. At one end sat the priest with the money of the union in his hands. The president of the local union sat at the other end of the table. I marched down the aisle.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“Holding a meeting,” said the president.

“What for?”

“For the union, Mother. We rented the church for our meetings.”

I reached over and took the money from priest. Then I turned to the miners.

“Boys,” I said, “this is a praying institution. You should not commercialize it. Get up every one of you and go out in the open fields.”

They got up and went out and sat around a field while I spoke to them. The sheriff was there and he did notallow any traffic to go along the road while I was speaking. In front of us was a schoolhouse. I pointed to it and I said, “Your ancestors fought for you to have a share in that institution over there. It’s yours. See the school board, and every Friday night hold your meetings there. Have your wives clean it up Saturday morning for the children to enter Monday. Your organization is not a praying institution. It’s a fighting institution. It’s an educational institution along industrial lines. Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living!”

Tom Haggerty was in charge of the Fairmont field. One Sunday morning, the striking miners of Clarksburg started on a march to Mononglia get out the miners in the camps along the way. We camped in the open fields and held meetings on the road sides and in barns, preaching the gospel of unionism. The Consolidated Coal Company that owns the little town of New England forbade the distribution of the notices of our meeting and arrested any one found with a notice. But we got the news around. Several of our men went into the camp. They went in twos. One pretended he was deaf and the other kept hollering in his ear as they walked around, “Mother Jones is going to have a meeting Sunday afternoon outside the town on the sawdust pile.” Then the deaf fellow would ask him what he said and he would holler to him again. So the word got around the entire camp and we had a big crowd. When the meeting adjourned, three miners and myself set out for Fairmont City. The miners, Jo Battley, Charlie Blakelet and Barney Rice walked but they got a little boy with a horse and buggy to drive me over. I was to wait for the boys just outside the town, across the bridge, just where the interurban car comes along. The little lad and I drove along. It was dark when we came in sight of the bridge which I had to cross. A dark building stood beside the bridge. It was the Coal Company’s store. It was guarded by gunmen. There was no light on the bridge and there was none in the store. A gunman stopped us. I could not see his face. “who are you!” said he. “Mother Jones,” said I, “and a miner’s lad.” “So that’s you, Mother Jones,” said he rattling his gun. “Yes, it’s me I said, “ and be sure you take care of the store tonight. Tomorrow I’ll have to be hunting a new job for you.” I got out of the buggy where the road joins the Interurban tracks, just across the bridge. I sent the lad home. “When you pass my boys on the road tell them to hurry up. Tell them I’m waiting just across the bridge.” There wasn’t a house in sight. The only people near were the gunmen whose dark figures I could now and then see moving on the bridge. It grew very dark. I sat on the ground, waiting. I took out my watch, lighted a match and saw that it was about time for the interurban. Suddenly the sound of “Murder! Murder! Police! Help!” rang out through the darkness. Then the sound of running and Barney Rice came screaming across the bridge toward me. Blakley followed, running so fast his heels hit the back of his head. “Murder! Murder!” he was yelling. I rushed toward them. “Where’s Jo?” I asked. “They’re killing Jo – on the bridge – the gunmen.” At that moment the Interurban car came in sight. It would stop at the bridge. I thought of a scheme. I ran onto the bridge, shouting, “Jo! Jo! The boys are coming. They’re coming! The whole bunch’s coming. The car’s most here!” Those bloodhounds for the coal company thought an army of miners was in the Interurban car. They ran for cover, barricading themselves in the company’s store. They left Jo on the bridge, his head broken and the blood pouring from him. I tore my petticoat into strips, bandaged his head, helped the boys to get him on to the Interurban car, and hurried the car into Fairmont City. We took him to the hotel and sent for a doctor who sewed up the great, open cuts in his head. I sat up all night and nursed the poor fellow. He was out of his head and thought I was his mother. The next night Tom Haggerty and I addressed the union meeting, telling them just what had happened. The men wanted to go clean up the gunmen but I told them that would only make more trouble. The meeting adjourned in a body to go see Jo. They went to his room, six or eight of them at a time, Until they had all seen him.

We tried to get a warrant out for the arrest of the gunmen but we couldn’t because the coal company controlled the judges and the courts. Jo was not the only man who was beaten by the gunmen. There were many and the brutalities of these bloodhounds would fill volumes. In Clarksburg, men were threatened with death if they even billed meetings for me. but the railway men billed a meeting in the dead of night and I went in there alone. The meeting was in the court house. The place was packed. The mayor and all the city officials were there. “Mr. Mayor,” I said, “will you kindly chairman for a fellow American citizen?” He shook his head. No one would accept my offer. “Then,” said I, “as chairman of the evening, I introduce myself, the speaker of the evening, Mother Jones.”

The Fairmont field was finally organized to a man. The scabs and the gunmen were driven out. Subsequently, through inefficient organizers, through the treachery of the unions’ own officials, the unions lost strength. The miners of the Fairmont field were finally betrayed by the very men who were employed to protect their interests. Charlie Battley tried to retrieve the losses but officers had become corrupt and men so discouraged that he could do nothing.

It makes me sad indeed to think that the sacrifices men and women made to get out from under the iron heel of the gunmen were so often in vain! That the victories gained are so often destroyed by the treachery of the workers’ own officials, men who themselves knew the bitterness and cost of the struggle.

I am old now and I never expect to see the boys in the Fairmont field again, but I like to think that I have had a share in changing conditions for them and for their children.

The United Mine Workers had tried to organize Kelly Creek on the Kanawah River but without results. Mr. Burke and Tom Lewis, members of the board of the United Mine Workers, decided to go look the field over for themselves. They took the train one night for Kelly Creek. The train came to a high trestle over a steep canyon. Under some pretext all the passengers except the two union officials were transferred to another coach, the coach uncoupled and pulled across the trestle. The officials were on the trestle in the stalled car. They had to crawl on their hands and knees along the track. Pitch blackness was below them. The trestle was a one-way track. Just as they got to end of the trestle, a train thundered by.

When I heard of the coal company’s efforts to kill the union officers, I decided myself to go to Kelly Creek and rouse those slaves. I took a nineteen-year-old boy, Ben Davis, with me. We walked on the east bank of the Kanawah River on which Kelly Creek is situated. Before daylight one morning, at a point opposite Kelly Creek, we forded the river. It was just dawn when I knocked at the door of a store run by a man by the name of Marshall. I told him what I had come for. He was friendly. He took me in a little back room where he gave me breakfast. He said if anyone saw him giving food to Mother Jones he would lose his store privilege. He told me how to get my bills announcing my meeting into the mines by noon. But all the time he was frightened and kept looking out the little window.

Late that night a group of miners gathered about a mile from town between the boulders. We could not see one another’s faces in the darkness. By the light of an old lantern I gave them the pledge.

The next day, forty men were discharged, blacklisted. There had been spies among the men the night before. The following night we organized another group and they were all discharged. This started the fight. Mr. Marshall, the grocery man, got courageous. He rented me his store and I began holding meetings there. The general manager for the mines came over from Columbus and he held a meeting, too.

“Shame,” he said, “to be led away by an old woman!”

“Hurrah for Mother Jones!” shouted the miners.

The following Sunday I held a meeting in the woods. The general manager, Mr. Jack Rowen, came down from Columbus on his special car. I organized a parade of the men that Sunday. We had every miner with us. We stood in front of the company’s hotel and yelled for the general manager to come out. He did not appear. Two of the company’s lap dogs were on the porch. One of them said, “I’d like to hang that old woman to a tree.”

“Yes,” said the other, “and I’d like to pull the rope.”

On we marched to our meeting place under the trees. Over a thousand people came and the two lap dogs came sniveling along too. I stood up to speak and I put my back to a big tree and pointing to the curs, I said, “You said that you would like to hang this old woman to a tree. Well, here’s the old woman and here’s the tree. Bring along your rope and hang her!”

And so the union was organized in Kelly Creek. I do not know whether the men have held the gains they wrested from the company. Taking men into the union is just the kindergarten of their education and every force is against their further education. Men who live up those lonely creeks have only the mine owners’ Y.M.C.As, the mine owners’ preachers and teachers, the mine owners’ doctors and newspapers to look to for their ideas. So they don’t get many.

Chapter 7 – A Human Judge

In June of 1902 I was holding a meeting of the bituminous miners of Clarksburg, West Virginia. I was talking on the strike question, for what else among miners should one be talking of? Nine organizers sat under a tree near by. A United States marshal notified them to tell me that I was under arrest. One of them came up to the platform.

“Mother,” said he, “you’re under arrest. They’ve got an injunction against your speaking.”

I looked over at the United States marshal and I said, “I will be right with you. Wait till I run down.” I went on speaking till I had finished. Then I said, “Goodbye, boys; I’m under arrest. I may have to go to jail. I may not see you for a long time. Keep up this fight! Don’t surrender! Pay no attention to the injunction machine at Parkersburg. The Federal judge is a scab anyhow. While you starve he plays golf. While you serve humanity, he serves injunctions for the money powers.”

That night several of the organizers and myself were taken to Parkersburg, a distance of eighty-four miles. Five deputy marshals went with the men, and a nephew of the United States marshal, a nice lad, took charge of me. On the train I got the lad very sympathetic to the cause of the miners. When we got off the train, the boys and the five marshals started off in one direction and we in the other.

“My boy,” I said to my guard, “look, we a going in the wrong direction.”

“No, mother,” he said.

“Then they are going in the wrong direction lad.”

“No, mother. You are going to a hotel. They are going to jail.”

“Lad,” said I, stopping where we were, “Am I under arrest!” “You are, mother.” “Then l am going to jail with my boys.” I turned square around. “Did you ever hear Mother Jones going to a hotel while her boys were in jail!” I quickly followed the boys and went to jail with them. But the jailer and his wife would not put me in a regular cell.

“Mother,” they said, “you’re our guest.”

And they treated me as a member of the family, getting out the best of everything and “plumping me” as they called feeding me. I got a real good rest while I was with them.

We were taken to the Federal court for trial. We had violated something they called an injunction. Whatever the bosses did not want the miners to do they got out an injunction against doing it. The company put a woman on the stand. She testified that I had told the miners to go into the mines and throw out the scabs. She was a poor skinny woman with scared eyes and she wore her best dress, as if she were in church. I looked at the miserable slave of the coal company and I felt sorry for her: sorry that there was a creature so low who would perjure herself for a handful of coppers.

I was put on the stand and the judge asked me if I gave that advice to the miners, told them to use violence.

“You know, sir,” said I, “that it would be suicidal for me to make such a statement in public. I am more careful than that. You’ve been on the bench forty years, have you not, judge?”

“Yes, I have that,” said he.

“And in forty years you learn to discern between a lie and the truth, judge?”

The prosecuting attorney jumped to his feet and shaking his finger at me, he said

“Your honor – there is the most dangerous woman in the Country today. She called your honor a scab. But I will recommend mercy of the court – if she will consent to leave the state and never return.”

“I didn’t come into the court asking mercy,” I said, “but I came here looking for justice. And I will not leave this state so long as there is a single little child that asks me to stay and fight his battle for bread.”

The judge said, “Did you call me a scab!”

“I certainly did, judge.”

He said, “How came you to call me a scab?”

“When you had me arrested I was only talking about the constitution, speaking to a lot of men about life and liberty and a chance for happiness; to men who had been robbed for years by their masters, who had been made industrial slaves. I was thinking of the immortal Lincoln. And it occurred to me that I had read in the papers that when Lincoln made the appointment of Federal judge to this bench, he did not designate senior or junior. You and your father bore the same initials. Your father was away when the appointment came. You took the appointment. Wasn’t that scabbing on your father, judge?”

“I never heard that before,” said he.

A chap came tiptoeing up to me and whispered, “Madam, don’t say ‘judge’ or ‘sir’ to the court. Say ‘Your Honor.’”

“Who is the court?” I whispered back.

“His honor, on the bench,” he said, looking shocked.

“Are you referring to the old chap behind the justice counter? Well, I can’t call him ‘your honor’ until I know how honorable he is. You know I took an oath to tell the truth when I took the witness stand.”

When the court session closed I was told that the judge wished to see me in his chambers. When I entered the room, the judge reached out his hand and took hold of mine, and he said, “I wish to give you proof that I am not a scab; that I didn’t scab on my father.”

He handed me documents which proved that the reports were wrong and had been circulated by his enemies. “Judge,” I said, “I apologize. And I am glad to be tried by so human a judge who resents being called a scab. And who would not want to be one. You probably understand how we working people feel about it.”

He did not sentence me, just let me go, but he gave the men who were arrested with me sixty and ninety days in jail.

I was going to leave Parkersburg the next night for Clarksburg. Mr. Murphy, a citizen of Parkersburg, came to express his regrets that I was going away. He said he was glad the judge did not sentence me. I said to him, “If the injunction was violated I was the only one who violated it. The boys did not speak at all. I regret that they had to go to jail for me and that I should go free. But I am not trying to break into jails. It really does not matter much; they are young and strong and have a long time to carry on. I am old and have much yet to do. Only Barney Rice has a bad heart and a frail, nervous wife. When she hears of his imprisonment, she may have a collapse and perhaps leave her little children without a mother’s care.”

Mr. Murphy said to me, “Mother Jones, I believe that if you went up and explained Rice’s condition to the judge he would pardon him.” I went to the judge’s house. He invited me to dinner.

“No, Judge,” I said, “I just came to see you about Barney Rice.”

“What about him!” “He has heart disease and a nervous wife.”

“Heart disease, has he!”

“Yes, he has it bad and he might die in your jail. I know you don’t want that.”

“No,” replied the judge, “I do not.” He called the jailer and asked him to bring Rice to the phone. The judge said, “How is your heart, Barney!”

“Me heart’s all right, all right,” said Barney. “It’s that damn old judge that put me in jail for sixty days that’s got something wrong with his heart. I was just trailing around with Mother Jones.”

“Nothing wrong with your heart, eh!”

“No, there ain’t a damn thing wrong wid me heart! Who are you anyhow that’s talking!”

“Never mind, I want to know what is the matter with your heart!”

“Hell, me heart’s all right, I’m telling you.” The judge turned to me and said, “Do you hear his language!”

I told him I did not hear and he repeated to me Barney’s answers. “He swears every other word,” said the judge.

“Judge,” said I, “that is the way we ignorant working people pray.”

“Do you pray that way!”

“Yes, judge, when I want an answer quick.”

“But Barney says there is nothing the matter with his heart.”

“Judge, that fellow doesn’t know the difference between his heart and his liver. I have been out to meetings with him and walking home down the roads or on the railroad tracks, lie has had to sit down to get his breath.”

The judge called the jail doctor and told him to go and examine Barney’s heart in the morning. Meantime I asked my friend, Mr. Murphy, to see the jail doctor. Well, the next day Barney was let out of jail.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Most Dangerous Woman – Ani DiFranco & Utah Phillips