———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Saturday September 27, 1919

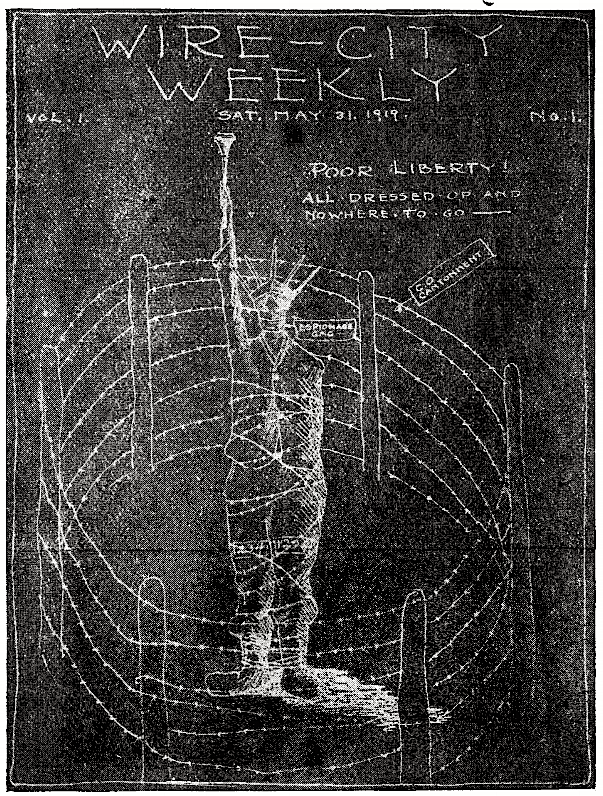

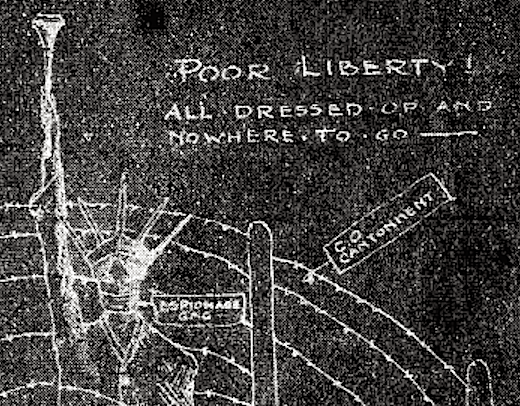

Leavenworth, Kansas – Wire City Weekly, Prison Magazine

From The Liberator of September 1919:

A Prison Magazine

THE latest and most daring enterprise in American radical journalism is-or doubtless we should say was-the Wire City Weekly. It is the product of a group of men whom the United States Government has imprisoned, tortured, and some of whom it has killed, in the effort to break their spirits. It is the last and most flagrant proof of the failure of that effort. It has already been extinguished by the huge hoof of American militarism; but it has existed, and should not be without honor among us.

The Wire-City Weekly. Published every week at Wire City, Kansas. Circulation-secret. One of the 1,500 Bolshevik papers in America. Barred from the Postoffice as First Class Matter.

So runs the description at the top of the editorial page. It is the organ of the Soviet in the United States Disciplinary Barracks, the military prison at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

This militant journalistic defiance of militarism is typewritten and carbon-copied, one or two columns to the page, on sheets of typewriting paper, with hand-made covers, one of which is reproduced here.

And its contents-well, what do you think its contents would be like? Guess again. It is not a record of the brutalities, the filth, the tyranny of Ft. Leavenworth. It is not a cry of protest. It is a variety of things, but first of all it is a very jolly, good-natured publication. It treats the prison very much as a witty dramatic critic treats a bad play-it laughs at it. It is a paper written by men who are interested in ideas. But it is not solemn. It has the easy, good-humored critical quality of the conversation of radicals the world over. It is the kind of paper Socrates and the other philosophers would have got out if the Athenian government had shut them all up in a dirty jail together; they would have gone on arguing, and making jokes about each other as well as about their jailors.

On the first page of the first issue is this “Lusty Birth-Cry”:

So clamant a community as Wire City was bound sooner or later to find a channel for its manifold vibrations. In the natal number of The Weekly, the promoters do formally invite the clamorous of all sorts to proclaim, declaim and acclaim through this organized medium. Wobbly’ poets and Socialist lecturers, religious seers and mystics, children of God and children of the Devil (particularly the numerous latter), anarchists, aliens, pro-Germans, pro-Americans, internationalists, Fenians, Sinn Feiners, Bolsheviki, Republicans, and EVEN Wilson Democrats are welcome to our columns.

The leading article in this first issue is by Carl Haessler, and deals with “The Gang Spirit and Morale.” Here is the opening.

The man who has never belonged to a gang is hardly human. He has missed the thrill and sweep of gang plans and gang successes and he has never felt the common strength with which a gang rises from defeats that would crush the individual. In short, the man has never known the gang spirit. Aristotle! the most influential of ancient philosophers, stated in practically so many words that Man is by nature a Gangster. The gang spirit runs in humanity’s veins.

The article goes on to discuss the ways in which governments manipulate the gang spirit for their own ends, and the limitations of this manipulation, when “morale”-creation meets with “demoralization,” and it ends with suggestions for an expansion of the gang spirit which will really serve the interests of humanity.

Carl Haessler, by the way, is the editor; his associates are C. H. Getts, H. D. Cohn, L. B. Marcowitz, J. B. C. Woods, and H. A. Simons. “Subterranean Correspondents,” Earle Humphreys, Jr., and Roderick Seidenberg (of the basements and sub-basements).

The editorial in this first issue is an admirable criticism of Wilson’s message to Congress. Then follows an announcement of the Walt Whitman centenary, to be celebrated by an all-day program on May 30th, the leisure of Memorial Day being dedicated to this purpose. The program includes a “hike” around Wire City, with chants of the songs of the open road by the Whitmaniacs, addresses and readings, and outdoor sports. Next is a short article on prison architecture and management. Poems including “An Adventure in Free Verse,” and jokes, including this one:

“Watch this space. We have nothing to put in it, but watch it anyway.”

One can imagine how this insouciant little magazine was handed around in the cells and read thin! The next issue is twice as large, with a sporting section in which the baseball game between the Religious C. O.’s and the Bolsheviks is described in detail. There is also a chess department. One learns moreover that the most widely read books that week were volumes by Bertrand Russell, Haeckel, Darwin, Eugene Sue, Carl Sandburg, Chekov, Dostoievsky, Galsworthy, Upton Sinclair, Walt Whitman. All the books newly arrived in prison are also announced.

[Study of the Bedbug.]

There is an article on Biology, dealing with the one specimen of animal life readily available for study under the circumstances, the bedbug; it is pointed out that the plants feed upon the earth, the herbivorous animals upon plants, man upon the herbivorous animals, and the bedbug upon man, it being thus proven that this insect is the ultimate crown and purpose of creation.

There is a page of announcements of “intellectual events,” namely, classes in logic, biology, philosophy, English and economics, conducted by various prisoners. There are political articles, and an editorial discussion of “The Conscienceless Objector.” It appears that

[T]he conscienceless objector resents being known as a C. O., as a conscientious objector, in a common lump with the socially futile anachronisms of the sterile sort. He aims at putting his mark on the community fabric, he plans to be socially productive, he conspires to shatter this sorry scheme of things entire and then remould it nearer to the heart’s desire.

In “Advice to Spring Poets,” H. Austin Simons judiciously undertakes to explain to the contributors who have been flooding the editorial tables with verse, the difference between prose and poetry. He tells them that what can be said should not be sung. To the extent that ideas, moral concepts, etc., become the subject-matter of poetry, the writer becomes a “didactic” poet; and

[D]idactic poetry is to the lover of the art what near-beer is to a bacchant; what “slum” [a kind of prison grub] is to the epicurean, what an old maid with hip-joint disease is to the young and ardent philanderer.

Most of the poetry submitted to the weekly, he says, is of this didactic class; and he offers a method by which any writer may discover whether he is really called to the service of the muse or whether it is a false alarm. The method is admirable, and in effect is this: Learn to write good prose, and put everything in that you can. What won’t go into prose, the things that you must sing instead of say, are poetry. In short, if you can possibly keep from being a poet, you aren’t one.

Nevertheless, a poem entitled “Plums” appears to have got past the editorial Cerberus. It is a pity that there isn’t enough room here to quote it. The commandant of the prison, to whom the fat, juicy plum of the prison-job has been handed, a plum “sweet with the luscious squirt of privilege and military glory,” is figured for us as an old woman preserving plums-

All that was passionate and vibrant in life

is lost to this old harridan

Except the lust for sweet-stinging juice of

the ripe, round fruit…But her senile joy is spoiled, for there are many anti-militarist worms wriggling defiantly in the heart of her plum, bittering its flavor.

Next week we find an editorial on the controversy between the right and left wings of the Socialist movement, entitled “The Right is Wrong.”

The fourth issue continues the discussion of world and domestic politics, and gives more and more space to the debate between the various factions among the prison radicals. And along with this it remains human and funny, with little personal notes and jokes, some of them unintelligible to an outsider, in the style of the village newspaper. There are signs, too, that this happy circle of free spirits is being broken up, as in this humorous “Obituary”:

Alexander, Americo V., one of the most esteemed inhabitants of Wire City, departed this life for a better world June 18, 1919. Despite the Department of Justice, which was called in during the last few days of Rice’s relapse, he failed steadily, and on the night of June 17 the revolutionary conclave administered extreme unction. The typos here, our readers, and all his acquaintances, wish him happiness hereafter. On his headstone have been inscribed these simple, touching words:

“Home-La Bonne Parole-Home.”

But there are Lusking Committees in the Wire City, too, alas! (For you have doubtless been wondering why we did not all move there and enjoy their freedom.) A “raid” conducted upon the offices of the Wire City Weekly by the prison authorities-it seems just like home, doesn’t it?-suggests the reason why we have received no more copies of the paper.

This week’s material, already set up, for the fourth issue, was seized from the editor’s table by a major. C’est magnifique, messieurs les officiers, mais ce n’est pas la guerre!*

And so, alas, an end of these articles, debates, jokes, book-reviews, poems, the efflorescence of a vitality which has made Ft. Leavenworth one of the intellectual centers of America. It will not do to let these young men talk and laugh so loud. It will especially not do to let America overhear them-lest America say to herself: “So prison is not so terrible after all, when you have an ideal to sustain you. They have not been broken. They laugh at their tormentors. They laugh even at themselves. They are happy. Why is it? Is this what Bolshevism means?” F. D.

*The editors have since been transferred to the prison-hell of Alcatraz.

[Detail of magazine cover added.]

[Emphasis and paragraph breaks added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

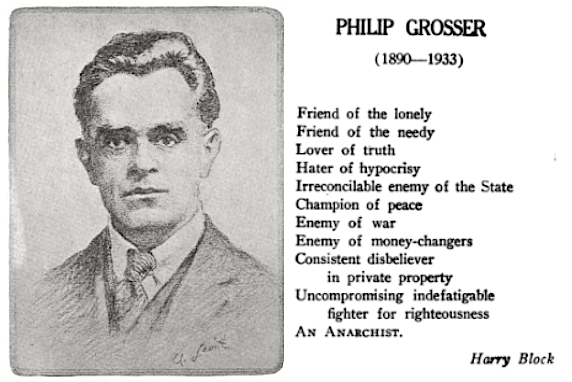

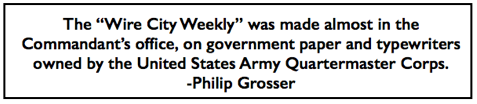

Quote P Grosser, Wire City Weekly, Prison Experiences of CO, early 1930s

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069746421&view=2up&seq=28

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-Sept 1919, page 48

Note: on page 42: H. Austin Simons on

-the Military Prison at Fort Leavenworth

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/09/v2n09-w19-sep-1919-liberator.pdf

See also:

Philip Grosser on Wire City Weekly

-and transfer to Alcatraz:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069746421&view=2up&seq=28

From:

Uncle Sam’s Devil’s Island

Experiences of a Conscientious Objector

in America During the World War

-by Philip Grosser

Boston, Mass., 1933

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069746421&view=2up&seq=8

Philip Grosser & Poem by Harry Block:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069746421&view=2up&seq=6

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069746421&view=2up&seq=4

Civil Disobedience

An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States

-by Mary Ellen Snodgrass

Routledge, Apr 8, 2015

(search: “wire city weekly”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=KWrxBwAAQBAJ

“These Strange Criminals”

An Anthology of Prison Memoirs

-by Conscientious Objectors from the Great War to the Cold War

-ed by Peter Brock

University of Toronto Press, Jan 1, 2004

(search: “wire city weekly”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=qmQjwwGIiyYC

The Lusk Committee

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lusk_Committee

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Masters of War – Bob Dylan

“You hide in your mansions while the young people’s blood

flows out of their bodies and is buried in the mud.”