You ought to be out raising hell.

This is the fighting age.

Put on your fighting clothes.

-Mother Jones

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Friday February 16, 1917

From Everett Labor Journal: Report on Industrial Warfare, Part II

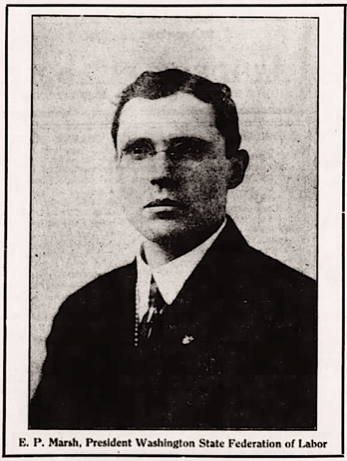

Over a period of three weeks, from January 26th to February 9th, The Labor Journal of Everett, Washington, published the “Report on Everett’s Industrial Warfare,” by E. P. Marsh, President of the Washington State Federation of Labor, which report he had delivered on the first day of that bodies annual convention, Monday January 22, 1917. Hellraisers Journal republished Part I of that report yesterday; we offer Part II today, and we will concluded the series with Part III of the report tomorrow.

EVERETT’S INDUSTRIAL WARFARE, PART II

EVERETT’S INDUSTRIAL WARFARE;

REPORT OF PRESIDENT E. P. MARSH

Activity of the Everett Commercial Club.

I wish it were possible with a short homily to end the story here, for the sorriest part of it now begins. It is to be expected that when two men are in a fist fight, the bystander will at least keep his hands off, or, when one has been terribly beaten, insist that the fight end and the men patch up their differences. The business interests of the city were the bystanders in this struggle, but by no means “innocent.” They had every right to say to the contending parties: “You fellows have fought long enough; why don’t you quit, find out what it is all about, and see if you can’t be good friends again?”

The business interests were suffering keenly because of this struggle. The strikers [striking Shingle Weavers of Everett] were living on short rations, little money to spend for groceries, meat and shoes. The strikebreakers were being housed on mill property, fed from a commissary, spending none of their money with Everett merchants. If the Commercial Club members had a right to take a hand in the proceedings, and naturally they felt they had, for they were being hurt, it was their bounden duty to honestly investigate the truth of the statements of the contending parties, approach the whole problem in a spirit of community good, offer conciliation and mediation to both contending parties. Now notice how they went about it.

Some months previously the Commercial Club had been reorganized on the bureau plan, the various activities of the business life of the city being chartered out and turned over to various bureaus. There was an advertising bureau, a transportation bureau, etc. It became a stock concern, stock memberships being issued in blocks to employers and business houses and some distributed among employers and their employes. What a field for an industrial bureau that would have kept in touch with the human side of the city’s industries, striven for industrial peace by studying the vexatious labor problem with an eye to helping along friendly relations between employers and their men. But there was no such bureau, at least not equipped to function in the social relationship of industry. Mistake No. 1 of the Commercial Club.

Presiding over the destinies of the club at that time was Mr. Fred K. Baker, owner of one of the struck mills, a gentleman who had but little love for unions, a believer in the “divine right” of employers to “run their own business.” The Commercial Club resolved to “investigate” the shingle weavers strike and a committee was appointed for that purpose. Along what line of information it conducted its investigations is not known to the writer. The writer does know that no union official, local or international, was ever spoken to by any member of this committee. The men in charge of this strike might reasonably be supposed to have some slight knowledge of its causes, but they were ignored. The committee completed its labors and reported back that after careful deliberation it had been found that the condition of the shingle industry did not warrant the increase of wages asked for and the report was adopted. Now, mark you, this in the face of the fact that International President Brown was in the city for the express purpose of appearing before the club and giving the weavers’ side of the contention and he was refused the floor. This episode would have been sufficient to make the Commercial Club lose caste among many Everett citizens. But this was but the beginning.

Dominated by a few powerful financial and manufacturing interests, the club was again placed on record in a still more positive way as being opposed to trade union activity and determined to give it the coup de grace. Everett had for many years been known far and wide as a strong union town. It erected the first union owned labor temple on the Pacific coast. The members of its unions averaged up in civic pride and civic virtue with any other class of its citizens. I distinctly recall attending a meeting of the Chamber of Commerce many years ago in Everett, at a time when the unions were in the very zenith of their power and prosperity, when Everett was enjoying a building boom and all the trades numerically strong. The meeting was called to discuss some labor matters then under investigation. A gentleman, then prominently identified with the First National Bank, volunteered the statement that there were more savings bank deposits in Everett, representing the savings of work people, in proportion to population, than in any other city in the Northwest. The large majority of Everett’s unionists are of the sober, industrious variety, owning their own homes, maintaining the city’s schools and churches and all civic institutions.

But the “open shop” bugaboo had hit this powerful clique in the Commercial Club and hit it hard. Everett had not recovered from an industrial depression that had been state-wide, affecting the locality where no unions existed as well as the organized locality. It occurred to these gentlemen that here was a chance to take a fling at its ancient enemy, the trade union movement, by declaring in effect that the “closed shop” policy of the unions was responsible for all the industrial ills Everett has suffered. As well ascribe the seven year plague of locusts that devastated ancient Egypt to the trade unions of that period. There had to be a goat and union labor and its “closed shop” policy was “it.” Our whole economic system was on the verge of delirium tremens when the European war happened along to check the disaster that was imminent and the Everett unions had no more to do with bringing that about than the mythical man in the moon. “Open shop” is a catch word that covers a multitude of employers in their artful pastime of skinning the America workman coming and going, in the practical operation of which the average citizen not a member of a trade union knows little. The trade unionists know from bitter experience. So the Commercial Club went on record for the “open shop” and the artful manipulators therein sat back and expected the trade union movement of Everett to go hurtling to ruin. But it didn’t hurtle-not noticeably.

Enter the Industrial Workers of the World.

A million stories and rumors have been told the world concerning the activities of the Industrial Workers of the World in Everett, the treatment accorded to them and their subsequent action. These rumors I shall utterly disregard and chronicle here indisputable facts. The bare facts are hideous enough and disgraceful enough to make us wish to forget the nightmare we have been through, rehabilitate the name of our fair city in the eyes of the world, wipe the slate clean of terrible mistake of judgment and commission, adopt a more kindly, Christian spirit in dealing with our vexatious social problems.

I never have and do not now subscribe to the doctrines and industrial practices of that organization. I cannot see in the direct action, sabotage methods of that body anything constructive. I believe that as changes come in our method of production and distribution it will be because of a growing intelligence on the part of thoughtful, practical people. A revolution is going on in the minds of the people today, bloodless, physically peaceful, but none the less sure. The whole viewpoint of society toward the human productive unit is undergoing a profound change. It is noticable in the work of countless social agencies throughout the length and breadth of the land; noticeable in the broadening out of government regulation and supervision over humble, everyday affairs of the average man; workman’s compensation and minimum wage legislation opened an entire new field of humanitarian endeavor on the part of state and federal governments which they are rapidly exploring; the well-being of the producer of today is becoming the immediate and pressing concern of society and is being rapidly so recognized. In this scheme of social construction I doubt the fitness of an organization whose “hand,” like Ishmael of old, is “against every man and every man’s hand against him.”

Be I right or wrong in this belief, I am American enough to believe and charitable enough to believe that every man beneath the flag should freely speak and write concerning his creeds or philosophy, his theories of government, his ideas of organization. Every man must hold himself amenable to the law of the land for the abuse of that right, for the use of obscenity or banal personalities. There is a well defined line of demarcation in the right of free speech. It does not include the right to wantonly insult, use scurrilous or obscene language in public places. It does not include the right to utter any thing under the sun in criticism of human institutions if done in language not obscene, vulgar or scurrilous. Take away that right and you have torn from its foundations the cornerstone of democracy. Understand that plain line of demarcation and you will understand why trade unionists uphold zealously the right of free speech, by anybody upon any subject. I concede the same right for an Industrial Worker of the World that I demand for myself, the right to air my particular beliefs, philosophies and grievances.

The strike had been in progress some little time when the activities of the Industrial Workers were first noticeable in Everett. Great pains have been taken to create the impression that the trade union movement of Everett invited them there. That is absolutely untrue. I cannot make that too plain nor too insistent. They came of their own volition and established a small headquarters. They shortly began street speaking and this was immediately resented by many business and manufacturing interests, who thought they saw in the preachments more trouble on an already afflicted community.

On February 18, 1913, a drastic anti-street speaking ordinance had been passed. It forbade street speaking upon Hewitt Avenue from Rockefeller to Rucker, or upon any other public place within one block north or south of that avenue. On October 27, 1914, through the work of Commissioner Salter, a new ordinance was passed, superseding the old one. It allowed public speaking upon any cross street, fifty feet back of the main street either north or south, save upon South Wetmore, upon which street there was a fire station, the reason for this exception being obvious. This was the ordinance in effect when the crusade against the Industrial Workers took place. They chose Wetmore Avenue, just north of Hewitt, and were careful to place their platform just back of the fifty foot line.

In the neighboring city of Seattle they have been holding their street meetings for years in the lower end of the city. The whole policy of the authorities there was to let them talk as much as they pleased as long as they did not obstruct traffic. But in Everett the situation was tense and manufacturing interests involved in this strike were in an irritated frame of mind. The I. W. W. speakers denounced the owners of the struck plants for their unyielding attitude and declared that they proposed to help the shingle weavers win their strike. This was where the shoe pinched. Despite the state of public feeling I am firmly of the opinion that no trouble would have resulted had they been undisturbed as long as the language used was within the bounds of public decency. The usual crowds gathered, some people sympathetic, some hostile, the majority merely curious. Men would stop and listen a few moments and pass on, as crowds do.

But certain citizens thought they saw in these nightly meetings a direct menace to the city, perhaps an attack upon life and property, I do not know. At any rate they determined to rid the city of the Industrial Workers of the World and to the astonishment of many who believed the regular police force amply able to quell any disorder that might arise, the papers suddenly appeared with a public call for citizens to be deputized as deputy sheriffs in defense of the peace of the city. Several hundred citizens, including men high in business and professional life, answered the call and reported to the Commercial Club headquarters. They were sworn in by Sheriff McRae and armed patrols established as darkness fell each day. Just why this army should be mobilized at the Commercial Club when they were under the authority of the sheriff, instead of at the county jail, where county peace officers belonged, has never been satisfactorily explained. The county jail was practically the same distance from the street speaking corner as was the Commercial Club rooms. On several occasions this special army, assisted by the uniformed police of the city, stormed the street corner meetings and lugged the participants off to jail. Clubs were used freely and on one occasion bystanders in the crowd received the same gentle ministration from the business end of a club as did the offending I. W. Ws.

Again the law of physical force was working in full order and breeding the same brood of children, bitterness, contempt for constituted authority, retaliation, revenge. Think what you will of the I. W. W. and his doctrines, you cannot kill his beliefs with a club. That has never worked out yet and never will. He believed, zealously, wholeheartedly, in his philosophy, and he believed that if the constitution of the United States gave him anything—which he seriously doubted—it gave him a right to express that belief without let or hindrance. Those who would curb the freedom of expression of such men totally misunderstand the psychology of the crusader, be he religious or economist.

Stories began to filter out of brutal beatings in the jail where they were confined; of men being taken to the city limits, stripped and severely beaten. A boat load of them headed for Everett one day and were intercepted by Sheriff McRae, who is reported to have put a shot through the pilot house of the boat upon refusal to obey the command to heave to.

The Beverly Park Occurrence.

Events moved swiftly up to the night of October 30, when some forty I. W. Ws. landed at the dock from Seattle. They were met at the dock by members of the citizens’ posse and taken by automobile to Beverly Park, an interurban station not far outside the city limits. Here the [circumstantial ?] story goes that somebody suggested they run the gauntlet. They were accordingly compelled to run down the roadway to the track between two lines of infuriated men. Then they were headed for Seattle and told never to return.

Hearing of this occurrence, I accompanied several gentlemen, including a prominent minister of the gospel of Everett, next morning to the scene. The tale of that struggle was plainly written. The roadway was stained with blood. The blades of the cattle guard were so stained and between the blades were the fresh imprint of a shoe where plainly one man in his hurry to escape the shower of blows, missed his footing in the dark and went down between the blades. Early that morning workmen going into the city to work picked up three hats from the ground, still damp with blood. There can be no excuse nor no extenuation of such an inhuman method of punishment. It is not the duty of a peace officer to administer physical punishment to a prisoner unless resisting arrest, even though the prisoner be charged with murder. For what have we courts and criminal statutes if citizens temporarily clothed with the semblance of authority, may take it upon themselves to administer corporal punishment?

This incident was without doubt the culminating one in a series of brutal manhandlings that directly brought about the terrible tragedy of November 5, resulting in the loss of human life. It aroused the tiger in men, already smarting under a sense of injustice, and they determined that they would fight it out. Hence the call for volunteers and the openly declared purpose of coming to Everett the following Sunday and assert their right to speak upon the streets of that city. The law of physical force still at work, you see.

The Battle of November Fifth.

The story of that bloody Sunday has been an oft-told tale. I would weary you with a repetition of mere words. You know it as well as I. I hope I never live to see such an occurrence again. The passions loosed in the breasts of men and women, the lust for revenge, the curses and revilings heard upon every hand, were more sickening and heartbreaking than could be the sight of any number of dead men. The lost sanity, the reversion to savagery, the shattered belief in the sanctity of law, seeds of bitter enmity, mistrust and suspicion, these were the fruits of the law of physical force.

Seventy-four of the passengers of the ill-fated Verona lie in the Snohomish County jail awaiting trial for murder in the first degree. It is because of the fact that their trial is fast approaching, that they have exceptionally good legal talent to defend them, and it is probable that the actual facts of the killing will be established beyond dispute in court records, that I refrain entirely from relating the story of the arrival of the Verona and the subsequent battle. A great deal seems to hinge in a legal sense upon establishing whether the first shot was fired from the boat or from the dock. In a larger sense this, too, is immaterial. It was the tragic end of the law of physical force, whether invoked in the beginning by one side or the other, or both.

I am convinced in my own mind that these men had not the slightest intention of coming to Everett to attack life or property. If that were their intent they would hardly have discussed their plans publicly, called in a reporter for the press and given him a story of their intentions. Criminals rarely warn their victims that they are about to rob and burn and kill. These men, I tell you, were industrial zealots and beatings and inhuman abuse fed the fires of martyrdom that consumed them. The Beverly Park beating made them deadly determined that, come what might, they would establish their right to spread their industrial gospel on the streets of Everett, or anywhere else. I doubt if any of them ever dreamed they would be met with armed resistance.

The day set was Sunday, a day when men rested from their employment and the working people with their families were on the streets in large numbers. They calculated to come in force, march up the streets in broad daylight, and figured that the sympathy of the larger proportion of city’s population would prevent physical attack upon their forces such as they hitherto experienced. If there was an encounter, it would serve to still more strongly focus the eyes of the nation upon the struggle going on in Everett in the name of free speech and industrial freedom. It seems to me that this was their reasoning. That men would fall from a murderous gunfire never entered into their calculation. It is not surprising that a few men were armed. I venture to say that if you gather two hundred and fifty men upon any occasion and in almost any city, line them up and search their persons, you will find as many small firearms upon their persons as these men had in their possession.

[Photograph and paragraphs break added.]

SOURCE

The Labor Journal

(Everett, Washington)

-Feb 2, 1917

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88085620/1917-02-02/ed-1/seq-1/

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88085620/1917-02-02/ed-1/seq-4/

IMAGE

E. P. Marsh, Everett Labor Journal, July 23, 1915

https://www.newspapers.com/image/64503768/

THE EVERETT COUNTY JAIL

(Tune: “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Marching”)

By Wm. Whalen

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Songs_of_the_Workers_(15th_edition)

In the prison cell we sit

Are we broken hearted—nit

We’re as happy and as cheerful as can be,

For we know that every wob

Will be busy on the job,

Till they swing the prison doors and set us free.

CHORUS

Are you busy Fellow Workers

Are your shoulders to the wheel?

Get together for the cause

And some day you’ll make the laws.

It’s the only way to make the masters squeal.

Though the living is not grand,

Mostly mush and coffee and,

It’s as good as we excepted when we came.

It’s the way they treat the slave

In this free land of the brave

There is no one but the working class to blame

When McRea, and Veitch, and Black

To the Lumberyards go back

May they travel empty handed as they came.

May they turn in their report

That the wobs still hold the fort

That a rebel is an awful thing to tame.

When the 65 per cent

That they call the working gent

Organizes in a Union of its class

We will then get what we’re worth

That will be the blooming’ earth.

Organize and help to bring the thing to pass.

———-