———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday March 2, 1909

At Mexico City – John Murray Learns Details of Rio Blanco Massacre

John Murray recently returned from Mexico and has written an article about that experience for this month’s edition of the International Socialist Review. Below we offer part two of that article in which Mr. Murray arrives in Mexico City and hears the story of the Rio Blanco Massacre.

Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution

BY JOHN MURRAY

[Part II]

—–

—–

Black clouds gathered against the mountains and as the City of Mexico was reached the deluge broke.

A sandal-footed, brass-tagged “cargador” seized my bags and carried them from the Pullman’s steps to a blue-flagged coach.

I kept my face glued to the carriage window and asked myself this question: “Mexico, Mexico, Mexico is—what?” The answer seemed to rise from the passing throng of bent-backed, human burden bearers, “Mexico is a land of cargadores.”

With leather thongs passed across their foreheads and around their heads, cargadores carrying as much as three hundred pounds, trotted by without a stumble. And in the steps of these men followed the women and children likewise loaded.

In no other country in the world does the human back so stagger under a dead weight as here in Mexico.

Arriving at the hotel in front of the Alameda, I went immediately to my room, locked the door and got out my list of addresses in cipher. It was a wearisome task to figure them out, one by one, but I dared not run the risk of being taken by the police and having them find names of Mexican revolutionists given me by the Junta in Los Angeles—that would mean prison for all. One person in Mexico in particular had been recommended to me by Magon. I would see him first.

On the street corner I caught a boy. For “cinco centavoes” he would guide me to the “Calle Misercordia.” (Let it be understood that the real names of people and of streets do not appear in these writings, where the life of a member of the Liberal Party in Mexico would be jeopardized.) We pushed through the evening crowd of home-going artisans, clerks and laborers. Venders of cakes and candies, their wares piled perilously high on oblong wooden trays poised on their heads, threaded their way through the throng without a mis-step or collision. Sellers of an endless variety of fried foods fed the passers by, their sizzling little stoves sending out a stream of strong odors from many door ways.

The lottery-ticket sellers were out, and on every block men, women and boys shook their paper fortunes enticingly in my face, crying out the number of thousand “pesos” that might be won from the Loteria Nacional for the quick payment of a few “centavos.”

Gamble. Why not? The government licenses it, the “pulque” shops incite it, and the average wage of the city workman being not over sixty “centavos” a day (you must divide this in half to get its value in American money), it must be plain that the only road of escape from gutter-poverty is the barest possible, hazy chance of a successful gamble. The city government has suppressed all other gambling with an iron hand. No mine in the Western Hemisphere can hold a candle to the wealth that flows daily into the hands of the government’s partners—the lottery lords of Mexico.

Wrapped in a raincoat I followed my guide through the crowds that jammed the narrow sidewalks. Beggars there were a plenty, blind beggars, led by boys who, grasping the wrists of their sightless charges, forced their upturned palms into the faces of the passers by; old beggars, standing or squatting in front of the churches, and with whining, musical voices holding out their hands for dole.

At the entrance of a court in the poor quarter of the town, my guide stopped. This was the number of the house that I had asked for in the “Calle Misercordia.”

I paid him his five coppers and he disappeared into the darkness.

Under the archway, by the light of a small lamp, I could see a family bedding themselves down for the night on the stone-flagged floor of the passageway, all unconscious that passers by to the second story must walk through their midst.

Climbing the stone stairway I knocked at the first door twice, and at the last rap the one whom I had come to see stood before me.

If all Mexico loved Ricardo Flores Magon, Magon loved this man beyond all others in Mexico. Broad-shouldered, curly-headed and almost cat-like in the grace of his firm, agile movements, the grasp of his hand sent confidence and enthusiasm through my veins.

He read my letter [of introduction] slowly to the end, turned to me with a smile almost womanly in its sweetness, and welcomed me to Mexico. “Friend of my friends, how is Ricardo?”

I gave him the latest news from across the border and he plunged immediately into the Mexican situation.

“Senor, one month from today you must be out of Mexico back into the United States, for the way may be blocked. You know the reason why?”

I gave him the date set for the uprising as it had been told to me.

“Yes,” he solemnly asserted, “the anniversary of the massacre of the patriots of Vera Cruz.”

I told him of the methods of handling peon labor, as related by the American on the train.

He clinched his fists until the nails bit into his palms.

Why did he not call things by their right names, this Yankee planter? We still have slaves in Mexico. Over half the population, eight million souls, sweat under this system of peonage. The law is a dead-letter and the debts of the fathers are transferred to the sons. Once in debt always in debt; such is Mexican peonage.

“And will they revolt?” My question was well timed.

He stopped in his stride and came close to me, thrilling.

Wait ’till you have seen this city with its poverty-stricken people packed like maggots in every nook and cranny of the poor quarters of the town. Wait ’till you have read the police reports showing that three-fourths of the city’s dead are buried in paupers’ graves. Wait ’till you have gone south through the Valle Nacional, into which forty thousand Mexican working people have disappeared in the last few years, driven like cattle into the jungle-men and women—to furnish the tobacco planters with labor for the feeding. Wait ’till you have seen our overflowing prisons, the factories of Rio Blanco, where nearly a hundred men, women and children were shot down but a few months ago [January 7-8, 1907] for protesting against a reduction of wages. I was there; I saw it, and the facts are not denied. Wait, I say, until you have seen a small fraction of all that has been stirring Mexico to a seething mass of hate, fear and desperation, and then, believe me, you will acknowledge that this country is as certain to overthrow the government of Diaz as water is to run down hill!

“But have you the organization? Have you the guns to grapple with Diaz and his army of sixty thousand men?”

His answer came in fierce, short sentences:

Arms! I would give my life for them. Yet some have already been secreted and more are on their way from abroad. As for the army of Diaz poof,”—he blew through his fingers, significantly, “they will turn to our side at the first opportunity. You have not seen our army? Ah! it will remind you of the chain gangs common in your country. A Mexican soldier is a prisoner, sentenced to serve a term in the ranks, and the barracks of Mexico are mere penitentiaries. Do you know what a soldier of Diaz is paid? No? I will tell you—eight and a half cents a day. And from this he must feed himself and his family. Is it any wonder that he drinks, that he smokes marihauna, a drug much worse than opium, in order to forget his fate?

He looked at me intently, studying the effect of his arguments and reading my mind, added one thing more, most startling in its suggestiveness:

There is also a general. Is that enough?

I nodded assent, eager to ask him more, but he suddenly held up his hand for silence and turning towards the door, snapped out a question like a pistol shot.

“Speak! Who is it?”

A woman had come into the room as soundless as a ghost, and was waiting for him to notice her.

“Herbierto, it is I; they will be waiting. It is time for you to go.” Her voice was like deep water running over stones, a cooling melody.

Grasping my hand, he led me towards the graceful, black-eyed woman.

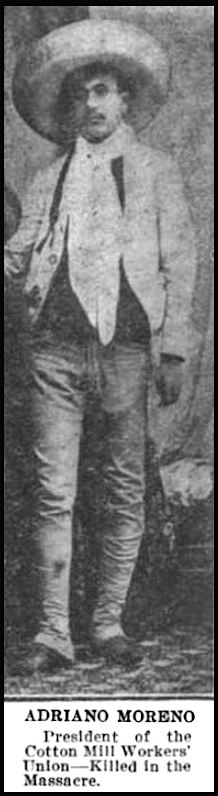

This is Senora Moreno; her husband and little son were shot in the great strike at the Rio Blanco mills. She is one of the best workers in the revolutionary group that meets tonight. Come, you shall go with us and see some Mexican patriots.

It was while crossing the Plaza de la Lagunilla that I first noticed the gendarmes’ lantern lit and standing in the middle of the street-crossing—the lantern that shines throughout the night all over Mexico.

The first lantern I barely glanced at—the gendarme with his revolver standing in the shadow, I did not see—but when another, and another, and another in the center of the center of all the main street-crossings flashed their signal lights back and forth, I saw the point. It was the military eye of Diaz burning in the night for fear the revolution might slip up and catch him in the dark.

Nothing shows the cat-watchfulness of Diaz more than this. He is always on his guard, for he knows that the revolutionists are sleepless; that their plotting never stops, night or day, and that if, for a time, they are beaten back into the mountains and the jungles it counts as a mere respite from the invincible bloody death-grip of the revolution. The Republic is practically under martial law.

Tell him the story of the mill, Felicita. It may be hard to touch the wound, but it is for the good of the cause.

Thus abjured by Herbierto, the woman walking at my side broke silence.

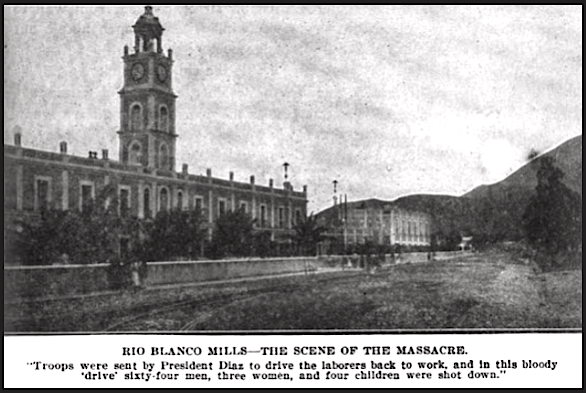

Before the gateway of the biggest mill in Mexico is camped today a regiment of soldiers.

This is in Orizaba, the Manchester of Mexico, and the mill’s name is Rio Blanco, the largest cotton-print mill in the whole world.

Twelve acres are covered with the Rio Blanco’s turning wheels, the very latest and most expensive machinery known to the manufacturers of cotton goods.

All this machinery comes from England—all except the Mexican military machinery furnished by President Porfirio Diaz and installed in front of the superintendent’s office.

The mill hands stream in and out between the ranks of soldiers, sullen and silent, with their faces turned from the guns to the ground. Their only hope of obtaining work is within the mill, where the men are paid thirty-five cents, the women twenty-seven cents, the children five and ten cents for a day of sixteen hours.

“Why are the soldiers there?”

Because the mill hands did not always turn their faces from the guns.

There was a strike. Troops were sent by President Diaz to drive the laborers back to work, and in this bloody “drive” sixty-four men, three women and four children were shot down.

After the dead were buried the widows and orphans returned to work in the factory, but they turn their faces to the ground as they daily pass between the ranks of soldiery.

There was not a tremor in the woman’s voice, and yet I could have wept at her even-toned, impersonal telling of the tragedy. A dead child and a dead man—her man, her child—small things in the path of Diaz, but if this woman could have her way the President would pay for them with his life.

[Emphasis added.]

[Part II of III, to be continued.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1908 to June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

ISR Mar 1909

“Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution” by John Murray

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA641

Arrival in Mexico City

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA648

See also:

Hellraisers Journal – Monday March 1, 1909

Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution by John Murray, Part I

From Juarez to Mexico City – John Murray Talks with an American Cane-Grower

Jan 7-8, 1907

Rio Blanco Massacre, Orizaba, Veracruz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%ADo_Blanco_strike

https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rio-blanco-strike

Barbarous Mexico

by John Kenneth Turner

C. H. Kerr & Company, 1910

https://books.google.com/books?id=8-IUAAAAYAAJ

Capter XI-Four Mexican Strikes: Rio Blanco, pages 197-206

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8-IUAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA197

Barbarous Mexico

-by John Kenneth Turner

University of Texas Press, May 12, 2014

(search: “john murray”)

Note: Introduction by Sinclair Snow leads to short bio of John Murray and indicates that his trip to Mexico occurred in May of 1908.

https://books.google.com/books?id=15GhAwAAQBAJ

Dreams of Freedom:

A Ricardo Flores Magón Reader

-ed by Chaz Bufe and Mitchell Cowen Verter

AK Press, 2005

(search: “john murray”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=JHOd18yUxrAC

The International Socialist Review, Volume 11

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1910

https://books.google.com/books?id=8-05AQAAMAAJ

ISR of October 1910

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8-05AQAAMAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA193

“Mexico Replies to the Appeal to Reason”

-by C. M. Brooks

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8-05AQAAMAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA211

Until men like John Kenneth Turner and John Murray and others began to pry into the affairs of Mexico and disturbing newspapers and magazines to publish the truth about them, the working people of the U. S. had no way of learning of the miseries of their comrades. And it is highly important that the American people continue to be deceived in regard to the character of the President of Mexico and his miscalled republic. Otherwise it might prove impossible for the United States Government to support Diaz when the Mexican people arise to demand a democratic form of government.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Corrido de Los Martires de Rio Blanco del 7 de enero de 1907