———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Monday March 1, 1909

From Juarez to Mexico City – John Murray Talks with an American Cane-Grower

John Murray recently returned from Mexico and has written an article about that experience for this month’s edition of the International Socialist Review. Below we offer part one of that article in which Mr. Murray travels from Ciudad Juarez to Mexico City and speaks with an American cane-grower along the way.

Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution

BY JOHN MURRAY

[Part I]

—–The third uprising of the Liberal Party failed but another is preparing in Mexico that will not be so easily snuffed out by President Diaz and his “partners,” so asserts the writer of this article, John Murray, who saw Mexico a few months ago in the fever-heat of revolt. With credentials from the revolutionary leaders he traveled from one Liberal Party group to another and was shown by them the underside of Mexico-the Mexico that President Diaz hides from view and guards with guns in hourly fear that it may rise and end his dictatorship.—Editor.

HE warm clasp of Tom’s hand tempted me to talk—in a moment, and my loose tongue let slip enough to give hint of my errand to Mexico. Now Tom Hart was the last man that I should have supposed would show the white feather—a bear hunter, mind you, and grizzlies at that.

“Look here, Bud,” he spoke with a down-drop of his eyes that was new to me, “don’t be so foolish as to rub the President’s hair the wrong way. You don’t know Mexico—it’s prison or death down here. You’re fooled if you think for a moment that this is the United States. Why, I have seen a bunch of rurales ride into a village before sun-up, where things were not going to suit the Diaz government, and call out the whole population, line ’em up and shoot down every tenth man. No trials. Nothing. That’s Mexico. And don’t you go for to stand on your dignity as an American citizen, thinking that you’re safer than a native to speak your mind free. I’ve seen Americans—yes, and there’s three of ’em right now in the prison of San Juan de Ulua—who might just as well be Esquimaux for all the protection that their nationality gives ’em. For God’s sake, old man”—Tom’s pleading startled me, for if he were possessed of such a crushing fear of Diaz what chance had I to escape contagion?—”don’t do anything to offend the Mexican government.”

“It’s too late, Tom, I’m into it now—up to my neck. You never held back when we were after the big-footed grizzly that killed our cattle in the pines back of the Loma Pelon ranch. The game I am after now is news—the true story of Mexico’s sandaled-footed burden-bearers and their nearness to revolt.”

For several minutes he said nothing, and the grind of the car wheels got on my nerves. We were racking through that strip of sandy desert which lies between the Rio Grande and the fertile cattle ranges of General Terrasaz’ eight-million-acre ranch. Would he never speak? It was hot to suffocation and I made a motion as if to rise from the seat, but his hand checked me.“How are you going to do it, Bud? What’s your plan?”

I had to think for a moment before answering. From now on until I recrossed the line back into the United States, I must trust people—people whom I had never seen before, whose native tongue was not my tongue, and whose lives would be in my hands, as mine would be in theirs. So why should I not trust my old partner, although he was not a member of the Mexican Liberal Party?”

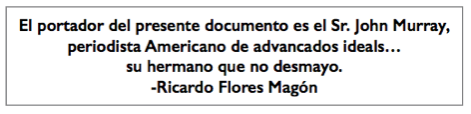

The cars seats next to us were vacant—I made certain of this with a glance—and opening my check book I extracted from a slit in the cover a thin, closely written sheet of paper, dated from the Los Angeles county jail, which was to pass me through forbidden paths in Mexico. Tom read my introduction to the revolutionists, slowly, from the first word to the last:

El portador del presente documento es el Sr. John Murray, periodista Americano de advancados ideals—” being the first line, and winding up with— “su hermano que no desmayo.

R. FLORES MAGON.

Refolding the letter he handed it back to me without a word and I rebedded it securely in the leather cover of my check book.

“Tom, you’ve heard of Magon, the leader of the Liberal Party?” I dropped the sound of my voice to the last notch and the answer came back in the same key:

“Every peon in Mexico knows him, Bud. He’s worshipped next to Juarez—but he’s got no chance. If it was Texans, now, that were coming over the border, I’d say ‘yes’ and oil my rifle with the rest, but how ever willing these poor Mexicans are to fight, I’ve got just one question to ask, and that’s a corker: ‘where’s the guns ?'”

“Well, Tom, maybe the guns are coming. I know that preparation—.” With a quick, upward motion of his finger Tom signified silence as the train came to a sudden stop and three Mexican officials entered the far end of the car.

I was dumb.

“Open your baggage for inspection,” called out the first of the three. The last man in this uniformed bunch gave silent emphasis to the demand by shifting his carbine from one hand to the other. He was a rurale with sugar-loafed sombrero, gray-coated, grim.

Pulling my suit-case out from under the seat I unlocked it and threw back the lid. There was nothing inside to make me nervous; that I had made certain of before leaving my hotel room at El Paso. Every scrap of paper that might give a clue to my purpose in Mexico had been carefully burnt, all—except the one thin sheet hidden in the lining of my check book.

I watched what happened to the other passengers whose turns for an overhauling came before mine.

A pink-faced American boy of twenty, whose Dunlap-shaped Derby labeled him from New York, began a sputter of high-keyed protests as the Mexican custom house inspectors pulled pearl-handled revolver, belt and cartridges from the rich youth’s valise and passed it to the rurale.

“Arms are not allowed in Mexico,” was the beginning and end of their explanation.

Tom first grunted in disgust and then leaned back upon the cushions until his head nearly touched mine.

“Say”—his lips barely moved and the sound of his voice carried no further than my ear—”that small-headed boy don’t seem to know that Mexico’s already loaded. It’s the rurales and police, carbines and revolvers, from Sonora to Yucatan. Diaz holds Mexico at the point of a gun.”

A man in uniform ran his hand through my kit. The contents of a parcel in one corner was not clear to him and he ripped a hole in the paper and asked the question:

“Camisas?”

“Three shirts,” I replied, and rearranged my rumpled luggage as the guardians of the customs left the car.

The train moved slowly out of Cuidad Juarez and I felt easier. If the Furlong Detective Agency, which had been following the members of the Mexican Junta all over the United States, already knew of my connection with the enemies of Diaz, the most likely place to hold me up would have been at the border, but now I was safely over the line.

Many dust-laden miles flew by the train as my old partner turned his ten years’ knowledge of Mexico inside out for my benefit. He dropped off that night at Chihuahua to strike back with his pack-train into the Sierra Madres.

On the morning of the third day there was a change sudden and startling. Dust, glare, alkali and desert, all had disappeared and in their stead had come the wet, warm heat of recent showers, with rushing streams banked by terraced gardens. The train was running rapidly through the fields of San Juan del Rio, four hours from the City of Mexico.

Seated opposite, on the leather-padded cushions of the Pullman’s smoking room, sat a barrel-of-a-man from Kansas. He pointed a fat, white fore-finger through the open car window at an object moving slowly across the brown, moist field.

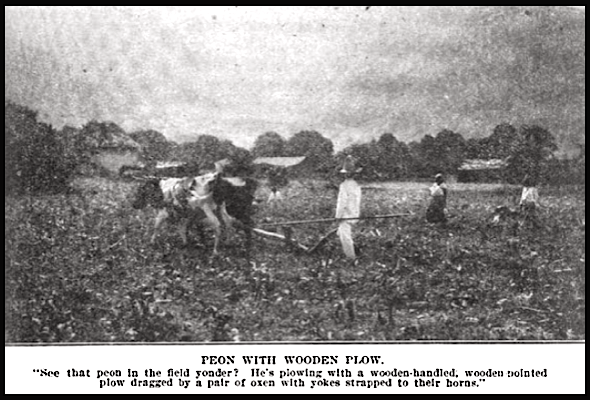

“Look!” His exclamation was one of disgust. “See that peon in the field yonder? He’s plowing with a one-handled, wooden-pointed plow dragged by a pair of oxen with the yoke strapped to their horns. Why, such things belong to the time of Christ! I’ll bet that white-robed, big-hatted scarecrow is not turning the soil three inches deep.”

A voice behind me answered him sharply:

“And suppose he was runnin’ a steam plow, what then? Could you and I come into Mexico and play the Lord-Almighty in the way we do? No, sir, It’s just this sort of thing that makes it possible for us to keep these people down.”

It was the unmistakable nasal twang of a Yankee, and I turned to size him up. Six feet tall, dressed in a linen suit and thin to a degree that made his weight a matter of bones, not meat, he seemed as unlike anything Mexican as could be found in the tropics. Dropping into the seat beside me he opened the way to conversation.

“Lookin’ for land or mines?”

“No, neither; just seeing the country,” I replied, and then adding cautiously, “for pleasure.”

Plainly doubting the probability of anyone’s coming to Mexico except to make money, the man stretched his long legs a foot or so further in front of him and was silent for the space of two minutes. Then he tried another pry at the lid covering my mystery.

“Tobacco prices ’bout struck bottom. Market’s cornered here same as in United States.”

“You grow tobacco?” I politely asked.

“No, cane.” And then feeling sure that I was merely an extra cautious investor who must be shown the absolute certainty of big profits before I would loosen up, the hatchet-faced, bean-pole of a man began to give me glimpses of golden opportunities.

“The land here is productive beyond anything dreamed of in the States,”—I nodded assent—”but the real gold mine is the native labor. You’re not opposed to ‘contract labor,’ are you?”

He leaned forward and studied my face.

“Why, not if it pays,” I slowly answered.

With a look of relief and pleased appreciation of my view point, he lowered his voice to a confidential pitch, saying, impressively, “All wealth comes from labor (this startled me a bit, for it sounded like the commencement of a socialist speech), and here, in Mexico, you can buy more labor for less money than any place in the world’ Its a gold mine for those who know how to work it.”

Seeing my opportunity to draw him out I expressed some doubts. “Yes, but wages are going up, even here in Mexico, and I’ve heard of strikes.”

He laid his bony hand on my arm. “Don’t you think it. The Mexican government has warned all employers not to raise wages—and a warning from Diaz means an order.”

We looked at each other in silence; he studying me closely, and I covered my real feelings with the air of a business man wary as to investments.

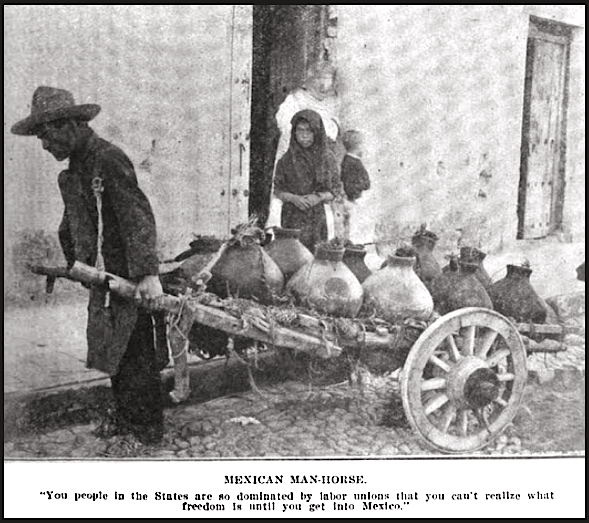

Apparently satisfied, he went on, “You people of the States are so dominated by labor unions that you can t realize what freedom is till you get into Mexico. Why, here the police think no more of allowing agitators to run around loose than they would mad dogs. Diaz cleaned out the last of ’em some months ago. They’re either over the border or in prison. That fellow Magon—maybe you know where he is?”

I looked the question.

“No? Well, he’s in jail in Los Angeles. He was the worst. Those of his miserable followers that were caught alive in Mexico—it’s seldom they are caught alive—are now in the prison of San Juan de Ulua, the military camps of Yucatan, or in the Valle Nacional. Mexican law cuts to the bone.”

I showed small interest in what became of those disturbers of the Government, and the canegrower returned to the strictly business side of the question.

“You see, the Mexican peon has no hope of ever owning a foot of land or saving a ‘centavo,’ and consequently Mexico gives the greatest opportunities on earth to reap a harvest from labor. It’s practically only the cost of their keep that we calculate upon. The little money that goes out in wages all comes immediately back to the hacienda stores. Last year our store cleaned up $15,000 for us and we’ve never had more than $5,000 worth of merchandise on its shelves.”

Following his lead of money talk I warmed up to the trade possibilities of the country and put a question to him:

“I am told that you can buy gangs of peons from the government, and that it pays?”

His face took on the shadow of a grin.

“Well, you might as well get it straight before you settle in Mexico. We do not buy this forced labor directly from the government, but we do pay from thirty to forty dollars a head for it—to contractors. In many cases these contractors are also the ‘Jefe Politicos’ or political heads of their districts. Take my advice-always stand in with the Jefe Politico. He’s ‘the man behind the gun’ in this country.”

The fat man from Kansas had been listening and the picture of peonage drawn by the cane-planter seemed to have made a bad impression. He waggled his head slowly from side to side, and finally asked a hesitating question.

“All this may be profitable for a time, but don’t you think it will lead to an uprising?”

“Uprising!” the planter fairly snarled a protest. “Uprising when there are over sixty thousands troops distributed over the nine military zones in Mexico! Let me tell you that the army is given President Diaz’s personal attention. It was only last week that the papers printed news of the completion in the arms factory of Newhauser, Switzerland, of the 3,000 automatic rifles invented by General Mondragon, and if they prove as effective as they are said to be, the entire army will be furnished with them.”

“That’s the trouble; its despotic,” objected the man from Kansas. “I’m told there’s not been a popular election in Mexico for over thirty years.”

“No, thank God,” rasped out the Yankee planter, “there’s not been one—not one. Think, man! what would happen to Diaz, cheap labor, and our interests, if the Mexican peon was allowed to vote?”

[Emphasis added.]

[Part I of III, to be continued.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1908 to June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

ISR of March 1909

“Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution” by John Murray

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA641

See also:

Tag: Mexican Revolutionaries

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mexican-revolutionaries/

Benito Juárez

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benito_Ju%C3%A1rez

Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junta_Organizadora_del_Partido_Liberal_Mexicano

“Behind the Drums of Revolution” by John Murray

–The Survey of Dec 2, 1916

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=5U05AQAAMAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA237

Radicals in the Barrio:

Magonistas, Socialists, Wobblies, and Communists

in the Mexican-American Working Class

by Justin Akers Chacón

Haymarket Books, Jun 26, 2018

(search: “john murray”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=6FVeDgAAQBAJ

“U.S. Socialists and the Mexican Revolution”

— Dan La Botz

Against the Current, 149, November-December 2010

https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/atc/3103.html#R30

John Murray, writing for The Call of New York and the ISR, also produced dozens of articles that would inform and educate the Socialist Party and its periphery. Like John Kenneth Turner, Murray emphasized the existence of quasi-slavery and debt peonage. He met secretly with a revolutionary who told him, “We still have slaves in Mexico. Over half the population, eight million souls, sweat under this system of peonage.”(13) In other articles Murray described the repression under the Díaz regime with articles on prison and political prisoners.(14)

Sources for above:

13. John Murray, “Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution,” International Socialist Review (March 1909) Vol. IX, No. 9, 641-59.

14. John Murray, “The Private Prison of Diaz,” International Socialist Review (April, 1909) Vol. IX, No. 10, 737-52; John Murray, “The Mexican Political Prisoners,” (May, 1909) Vol. IX, No. 11, 863-65.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Northern Division Song – Corrido Villista – Mexican Revolution