When things are rearranged so that

I can help my fellow man best by helping myself,

…then, I shall love him more than ever.

-Eugene Victor Debs

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal – Monday October 5, 1908

Milwaukee, July: Eugene Debs Interviewed by Lincoln Steffens

From Everybody’s Magazine of October 1908:

Part II:

—–

[Debs on the Evils of Capitalism]

[Said Debs, without waiting for questions:]

To begin with, we Socialists know what the matter is: it’s Capitalism; and we know what the cure is: it’s Socialism.

“Words,” I muttered.

[Said he, drawing near and reaching out his hands:]

No. Capitalism is a thing, a system; it’s the organization of society under which we all live. And it’s wrong, fundamentally wrong. It is a system of competition for wealth, for the necessities of human life, and, a survival of the old struggle of the jungle, it forces the individual to be selfish, and rewards him for beating and abusing his fellow man. Profit is made the aim of all human effort, not use, not service. The competitive system sets man against man, class against class; it puts a premium upon hate; and love—the love of a man for his neighbor—is abnormal and all but impossible. The system crucifies the prophets and servants of mankind. It pays greed the most, honors highest the ruthless, and advances swiftest the unscrupulous. These are the fit to survive.

Debs seized my arm.

It’s wrong, isn’t it? It’s inherently unjust, inhuman, unintelligent, and—it cannot last. The particular evils you write about, graft and corruption, and the others about which I speak, the poverty, crime, and cruelty, they are evidences of its weakness and failure; the signs that it is breaking down.

“Why not wait, then, for it to break down?”

Debs drew back, rebuffed. [He said:]

Because we have minds. Man can under stand, and he can ride, the economic forces which now toss him so helplessly about, as well as he can the sea. And, having intelligence, he should. For human intelligence also is a force of nature. It could assist the process of evolution by searching diligently for the root of all evils as they arise.

“Panics and graft?” I suggested. “War, child-labor, crime, poverty?”

[He declared:]

All, all are traceable to one cause. Take the panic, for example. Men lie about it, cover it up. Why not look it in the face? It’s the proof that capitalists cannot handle industry, business, no, nor even money. And how can they when they are thinking, not of perfecting the machinery of life, but only of making profits out of it! So they don’t understand the panic. We Socialists do. The capitalists attribute it to a variety of causes, all but the right one: Capitalism, profits.

[Said Debs, waving me back:]

No, wait. They produce more than they want themselves, don’t they? Of course. They make goods to sell; not for use, primarily, but to make a profit. That’s their god; and that’s the devil, really. For see:

Reduce our eighty millions to one hundred and our great continent to an island. The hundred all are workers at first. Each produces all that he wants. That’s a low order of society. By and by they improve the tools, specialize their labor, and produce more. Steam, for example, applied to big, invented tools, does the work of a hundred small tools. Each man multiplies his productive capacity a thousand times. Should not the hundred on the island have all that they need?

“Unless the population has increased.”

[Debs continued:]

The more men, the more they produce. Every worker that can get at a machine can produce more than he needs himself. No, the hundred and the children of the hundred should have all that they want. But they don’t. And one reason is that some have much more than they need: in profits; capital; new capital, upon which, you understand, Labor must earn interest and a profit, for profits come first under Capitalism, and necessarily, or capital vanishes. But let’s go on.

Ten of the hundred own all the big new machines; twenty struggle along with the little old tools; and seventy have no tools at all of their own. The biggest, best tools are the trusts, and the ten who have them are the trust magnates, full-fledged capitalists. The twenty are beaten, but they don’t understand that yet; they are crying out against the trusts just as Labor used to mob machinery. Bryan represents them; he wants to return to the competitive system with its anarchy, waste, and wars. Taft represents the trust magnates, opposing only their necessary crimes.

We Socialists represent the seventy, who are the bulk of the population and the key to the situation. Consumers, as well as producers, they are the market, and when “too much” is produced they must buy the surplus. But they can’t. Having no tools of their own, and prevented from organizing effectively, they compete for the chance to get at the tools and sell their labor. That puts wages down. Receiving only a pittance of what they produce, they can buy back only a pittance. The surplus grows, a load on the market, till the crash comes, production halts, men are discharged, prices fall, and—there’s your panic.

“And the need of foreign markets,” I suggested. “Why wouldn’t the other islands meet the need?”

[Said Debs:]

They would, temporarily. If there were enough islands, Capitalism and wage-slavery might go on forever. But there aren’t enough and—the other islands have the same system.

“And the same panics,” Berger grunted, “thank God.”

Debs winced, and I, thinking (also, I guess) of the misery, exclaimed: “Why thank God?”

Debs answered: “Berger sees there the chance for a higher civilization.”

“Where?” I asked.

WHAT CAUSES PANICS?

[Debs pleaded:]

Oh, don’t you see? The limitations of the world’s market and the panics will force us some day to unite and solve our problem. And what is it? It’s the problem of distribution. That of production is in the way of solution already. With machinery constantly increasing the productive power of the worker, and the trusts cutting out the waste and disorder of duplicated plants, man can produce enough. The capitalists themselves say so when they ascribe their panic to “overproduction.” They are wrong there, of course. The panic is due, not to overproduction, but to under consumption.

No, the supply is there and so is the demand. The masses haven’t all they need, and yet there’s an abundance, a surplus. The hitch is in distribution. The capitalist, producing, not to supply the demand, but to get his profit, seeks to make the Hindu buy shoes he doesn’t want, while the American at home goes about ill-shod because, don’t you see, his wages, fixed by competition, won’t enable him and his kind to buy all they need. Profits, not losses, make panics; and panics make losses. The losses drive more small capitalists into the trusts or back to labor, and the suffering of all opens people’s eyes, spreads discontent, and stimulates action. Panics compel progress.

“And panics,” said Berger, from somewhere in the dark, “panics are periodic.”

“Business men are becoming more intelligent,” I observed. “They are forming associations, combines, pools, and, as you’ve said, trusts. They may govern production and distribution, too.”

“They can’t govern themselves,” said Berger. “They can’t control prices, because they can’t control their own human nature, which, bred under the sordid profit system, gets too strong for them. If they had one absolute trust, they might limit the output, but—”

THE PROBLEM OF DISTRIBUTION

“But why,” cried Debs, seizing my coat sleeve, ” why limit production while men are in need?”

“Well, then, they can raise wages.”

[Said Debs:]

Ah, that would postpone the panic, and the crisis, for a while, if it were feasible. But it isn’t feasible. In the first place, no one employer can raise wages. He must act with his competitors, and the meanest sets the pace. That’s why Organized Labor must raise its own wages. Capital can’t do it.

And there, by the way, you have the cause of child-labor. Many a well-meaning manufacturer would like to spare the children, but he can’t. If one glass manufacturer employs boys and girls, the others must do the same. No, capitalists, too, are victims of the competitive system.

“But a trust?”

[Debs answered:]

A monopoly has potential competition to look out for. If it were too generous with wages, new competitors would seize the chance, by paying a liv ing wage, to undersell the trust and buy it out. The system is ruthless, you see. The conflict between wages and profits is absolutely unavoidable. Capital and Labor can not get together for long. For assume now that there is one universal trust, privately run for profit, and no possibility of competition; even then Capital couldn’t raise wages high enough to make possible complete consumption of the surplus, without wiping out what Capital calls “legitimate profits.” And the moment Capital does that, it abdicates.

“How would Socialism do it?”

[Said Debs:]

By abolishing profits. Socialism will be an entirely different system. It will produce for use, not profit; and production for use is practically unlimited. Socialist society could produce ten times as much as we do now, because a cultured civilization would have ten times as many wants as we have. But if we found we were making more of one kind of goods than people could use, we would decrease the attractiveness of labor in that branch and increase it in another; and with workers schooled as we would school them (and as Germany is training them now) Labor would go much more easily from one machine to another.

“You think that is possible?”

[Said Debs:]

Why, we’ve just seen that Capitalism does it in its brutal way. It drives men from one place to another by the blind force of panics and starvation. Under Socialism, all industry would be intelligently managed as a trust manages it now on a small scale. And, freed from the brutalizing temptation of profits, it would apply civilized remedies in a civilized spirit.

THE ROOT OF THE EVIL

“Then it’s profits you want to abolish.”

[Said Debs:]

That’s it. We want the producers to get all they produce.

“Who are producers?”

[Debs explained:]

All who labor in any productive way, mentally or physically. We would get rid only of the capitalists, stockholders, and financiers, who rake off fortunes for themselves and leave property in machinery and wage-slaves to keep their children in idleness, folly, or vice, a curse to themselves and a burden on the race for ever and ever and ever.

“Who would stand the losses?”

[Debs answered:]

Those who stand them finally now, the masses. For capitalists may rise and capitalists may fail, but capital grows on forever.

“But if you took away the chance of profits, wouldn’t you take away all incentive—”

Berger sprang up, groaning, and just as Debs answered “No,” the bear said: “Yes.” We looked at Berger. “Yes, I say,” he thundered. “We take away all incentive to steal and graft and finance and overproduce and shut up the shop sudden. But,” and he came around and stood over me, “you,” he said, “you wouldn’t write except to get paid? And you wouldn’t come here and talk with us, except for profit? I get wages, good wages, but no more. Won’t I run my paper except for profit, and help in politics except for graft? Bah! I love my work.”

AS TO INCENTIVES

[Said Debs:]

Berger’s right. We all would do our work, as most of us do it now, without the incentive of a fortune in prospect. Wage-workers haven’t that. John Wanamaker, with all his millions, was proud to accept a job at $8,000 to run the Post- Office. Jefferson didn’t write the Declaration of Independence for pay. Wouldn’t a fireman save a child’s life if he didn’t get sixty dollars a month? And Harriman—wouldn’t he operate railroads for a salary? Of course he would.

” But,” said Berger, “he wouldn’t finance ’em except for the incentive of millions of profit.”

[Said Debs, pleading:]

Ah, no, men are better than you think; they are nobler now, and less selfish than your “economic man.” We have heroes of altruism under the present system.

“True,” I said, “but we haven’t enough of them to build a society on. Self-interest is safer than altruism.”

Socialists don’t propose to substitute altruism for self-interest.

“But you’d level men down and destroy individuality.”

“Haven’t I got individuality,” called Berger, “and Deps?”

“Yes,” I laughed, “too much, and so have most Socialists; but you all are products of the capitalist system.”

“But the capitalist system,” Berger retorted, “doesn’t it level most men down now ? Yes, it takes all the individuality, all the courage, self-respect, liberty, and beauty out of the great mass of men to produce a few—”

[Said Debs;]

And look at those few. I’ll leave your civilization to that test alone, the test of its most successful men: Harriman, Rockefeller, Morgan. They are the flowers of the system; not the roots, remember. No, the monstrous specimens we produce to-day of individual greed, cruelty, selfishness, arrogance, and—charity: not love, and not justice, but degrading, corrupting, organized charity—these are one of the results of the struggle for life and riches, and the other is that beast—the mob.

Debs paused; then, more quietly:

There would be emulation after competition is abolished. Men would vie in skill and service, and that would produce individuality and character, though of a different sort. A society where all men were safe would produce more such real men and women as you find in the well-to-do class now. We would level up, not down. We would let human nature develop naturally. And—this you must believe—if we took away the fear of starvation on the one hand and on the other the tremendous rewards for crookedness and exploitation; removed all incentives to base self-seeking, and arranged things so that the good of the individual ran, not counter to, as at present, but parallel with, the good of society, why, then, at last, human nature would stand erect, manlike, frank, free, affectionate, and happy.

“But we are off on the cure,” I said. “Let’s get back to what the matter is.”

[Said Debs:]

It’s this. Some men live off other men.

“But how does that account for war, for example, and graft; political corruption, ignorance, child-labor, crime, and poverty?”

WAGE-SLAVES

[Said Debs:]

We’ve accounted for poverty. We see the mass of men working for the few. That’s what we call wage-slavery, and it is slavery. You say they might quit work; that the boss will let them go. But I tell you the fear of starvation is the boss’s slave-driver. They don’t dare quit. You can’t leave a trust and get back, and maybe the trust controls the work in your trade. And then there’s the black list. Well, the wage-slaves work in competition, and they produce goods that they need but haven’t enough money to buy. That’s poverty. And the measure thereof is the riches of the exploiters of labor, industry, and finance, and of their children till vice exhausts the family and returns the grafted wealth through the dives and divorce courts back to society. And there’s one cause of capitalistic vice accounted for, as well as of poverty. And the other cause of poverty is the waste of competition and the artificial halt of production to keep up prices and profits.

” And crime?”

[Said Debs:]

Petty and professional crime are a result of poverty; high crime springs from wealth-seeking.

“But vice, intemperance?”

[Said Debs:]

Frances Willard began her career telling working people that they wouldn’t be so poor if they weren’t so intemperate. She closed saying that the poor weren’t poor be cause they drank; they drank because they were poor.

“But the rich drink,” I protested.

[Said Debs:]

Idly. What else have they to do? Among busy businessmen, intemperance is rare, and when it occurs is inherited or due to the abnormal tension of the gamble which much business is now; an abnormal vice itself.

THE CRUELTY OF CAPITALISM

[Debs continued:

Child-labor we have touched on before. It is simply the meanest form of the exploitation of human beings by human beings, and, as I showed, is due, not to any inherent cruelty in the employer, but to the system of which he also is a victim—the capitalistic system which puts profits first and children—

“How does your theory account for political corruption?” I asked.

[Said Debs:]

Why, you know about that. That’s the capitalist class corrupting government to maintain them and their system of labor exploitation.

“I don’t know that at all,” I objected. “Not all business men take part in the corruption of politics. Only those do that have privileges from the government, franchises, and the like.”

[Said Debs:]

Oh, you are thinking only of the big businesses, the railroads, public utilities, and so forth, which attend to the corruption of politics directly. But they do it for the rest of their class.

“No, they don’t,” I contradicted. “They do it for themselves. They don’t know they belong to a class.”

[Debs answered:]

I don’t charge all of them with class consciousness. Some of them do understand, but, whether they are intelligent or not, in that way they do make the government represent the business class. And, as for the smaller business men, they get the benefit. They contribute to campaign funds, and that’s the big source of corruption, or, at any rate, they vote for one or the other of the two parties which the big fellows have corrupted and control, both of them.

“For privileges,” I insisted. “Why isn’t that the root of the evil?”

Debs shook, his head, and, taking my arm in both his hands, he said:

No, it’s deeper than that. It’s profits. The big fellows corrupt and rob railroads, insurance companies, banks; they finance and exploit the corporations and trusts. What governmental privilege is there in these businesses to explain the corruption of them?

I’ll have to let the Single-Taxers answer that. I can’t. It’s crucial, but I was stumped, and Debs went on:

Privilege won’t account for it all. Profit, gain, private property, in land and natural resources, machinery, and all means of production, that is at the bottom of it. And if you call these privileges, why, very well, I’ll go along with you. For I believe myself that wage-slavery, the power to exploit labor and live off one’s fellow men, is a privilege; the greatest privilege left since chattel slavery.

“How do profits account for war?” I said.

[He answered:]

We saw the cause of wars when we looked around for foreign markets.

“And bad workmanship,” I proceeded, “one of the worst evils of the day?”

PROFITS AND BAD WORK

[Said Debs:]

We remarked that captains of industry were turned from productive effort to finance. Capitalism will take a man who is a natural born operator, say, of a railroad, make him president, and pay him salary enough to make him want more—profits. He gambles. He is taken into Wall Street; he sees how easy it is to exploit and finance. He is fascinated; he neglects operation; the railroad suffers; people are killed. Bad work that—for profits, for fascinating unearned profits.

[Debs added:]

So with the worker. Do you teach him, by example and precept, to love to turn a piece of wood to fit a place? No. He doesn’t know where the piece is to go. He works without interest, to live; he must; he works for wages. He sees the exploiters making their money easily; he hears industrial leaders, dishonest and self-indulgent themselves, insisting upon his honesty and industry. He understands; if he does more and better work his employer gets the benefit, not he. He rebels; he catches the capitalistic spirit. His boss robs him and the public; so he loafs, skimps, and robs the boss. All he is after is all the boss is after—money. That’s the system.

“Now for your remedy: Socialism,” I said. “What is it?”

WHAT IS SOCIALISM?

[Debs answered:]

You know the old stock definition: “The cooperative control and the democratic management of the means of production.” I’ll try another: Socialism is the next natural stage in the evolution of human society; an organization of all men into an ordered, cooperative commonwealth in which they work together, consciously, for a common purpose: the good of all, not of the few, not of the majority, but of all.

“How would that induce the worker to do good work?”

[Debs replied:]

Well, if there were no inspiration in the idea of a common good there would be the assurance of a full return for the product of his labor.

“But how could such a complicated system give any such assurance?”

[Debs stated:]

By abolishing capitalists and all non-producers.

“But managers—organizers?”

[Debs responded:]

They would be well paid. Men would be paid according to their social use; skill and ability would count, but so would the disagreeableness of a job; to get it done, society would have to make it attractive somehow—with short hours or big pay. For men would be free, you understand; much freer than now, and not only industrially, but politically, intellectually, religiously—every way. We would have no churches that didn’t dare preach Christianity. But the point is that nobody would get such pay as Rockefeller gets now.

“Not even if he corrupted business and government and churches and colleges and men,” said Berger.

“But Rockefeller did a service, you say yourselves,” I retorted, “when he socialized the oil industry.”

[Said Debs:]

“Yes, but hasn’t he been paid enough? A billion, they say. That’s too much; but let him have it. All we Socialists say is that he should not be allowed to buy up railroads and mines and natural resources, and neither should oil consumers go on paying his children fortunes for generations. No, we must get rid of the Rockefellers, and keep only the organization they build up.

“But,” I challenged, “if you took away Rockefeller’s trust, wouldn’t the other trust builders stop work?”

[Said Debs:]

Men don’t organize trusts because they want to, but because they must. Competition drives them to it, that and their instinct for organization. Trust building can’t be stopped; you might as well try to stop an ocean current.

WOULD MEN WORK UNDER SOCIALISM?

“But how would Socialism secure the services of eminent talent like that of the great organizers, instinctive operators, and natural managers?”

[Said Debs:]

The words you use to describe them, “instinctive,” “natural,” show that you think of them as born to a kind of work. They would want to do that kind of work. They couldn’t help falling into it, and Socialism would offer such men greater incentives and more opportunities than they have now: pay according to service, public appreciation, and the chance they yearn for: to do good work unfretted (and uncorrupted) by grafting high financiers who are keen, not for excellence (look at our railroads), but for—profits. We would release the art instinct of the race.

“Geniuses might respond,” I said, “but how about ordinary men?”

[Said Debs:]

All able-bodied persons of age would have to work, but they want to. I’ve heard convicts beg to be allowed to break stone. Man must be active, and a society that produced for use and not for profits would have plenty of work to have done, and all would have to help do it, excepting only the incapable. For them society must provide, as it does now, only better; more regularly, with justice, not charity. The first thing the Socialists abroad went after was the old-age pension, which gives worn-out workers the right to draw on society for sustenance. We want to remove from the earth the fear of starvation.

“How, then, will you deal with loafers and vicious persons?”

[Said Debs:]

They are abnormal, and, by removing the cause, poverty and riches, we should soon have no more of them. The idle children of the present rich would be without their graft, but they would foresee their predicament, and the best of them would go to work. Some of them seem to inherit from their parents talents which capitalistic society now gives them every incentive to neglect. Under Socialism-an inspiration, you realize, as well as an organization—they would probably exercise their abilities for the common good and their own greater satisfaction.

“Good,” I said; “but the idle poor?”

[Said Debs:]

They are made what they are just as the idle rich are. Take a willing worker, overwork and underpay him, keep him on the verge, and then when he and his kind cannot consume what they produce, discharge him. He leaves his family to hunt a job, and, finding none, tramps or commits a crime. His children suffer, go young to work; they learn that their father is a bum or a crook. They are discouraged. The father drinks; they drink. Their children are, the best of them, perhaps, criminals, and the others, vagrants. This you see, and you ask me what Socialism will do with them? I’ll tell you: we will treat, with physicians, as sick, the children that have inherited weak or wicked tendencies from parents and grandparents who lived under Capitalism.

Debs paused to restrain himself, then he concluded:

And we will stop making more by abolishing the cause—poverty and riches.

SOCIALISM AND ART

“If there is no rich, leisure class, what will become of art and culture and manners?”

“They will become common,” said Berger, and Debs said:

All men will have some leisure. They will come strong and well paid from their work, ready to enjoy healthily all the good things of the earth. There will be no ignorance. Education will be free, not only in the money sense, but intellectually. The schools will teach liberty and the trades, justice and democracy and work, beauty, truth, and the glory of labor, efficient and honorable. The arts will thrive, as they always have thriven, in a free, cultivated democracy.

“Who will do the dirty work?”

“Machines,” said Berger, “which clean my house now.”

[Said Debs:]

Yes, only machines that increase profits are introduced now. Apparatus of great utility exists, but is suppressed by Capital because human strength is cheaper, and improvements reduce profits. You doubt that? Ask the telephone and telegraph monopolies about the patents they own and don’t use. But let me answer the question fully. There always will be some work less attractive than other kinds, and we should have to offer more pay or shorter hours to induce men to do it; men who want time to do unproductive things.

“If some men would get more pay than others,” I asked, “why, then, couldn’t they accumulate property?”

SOCIALISM FOR PRIVATE PROPERTY

[He answered:]

They could. Socialism does not abolish private property, except in the means of production. We want all men to have all they produce, all; we are for private property; it is Capitalism that is against it. Under Capitalism only the few can have property. And so with the home; and love. Capitalism is against homes. It makes it in expedient for young workers to marry; that makes for prostitution, which is against the home. And so is the tenement system of housing, which is good for profits and rents, but bad for homes and—love. And so is marriage for money against love.

“But, Debs, you must admit that you Socialists preach class war, and that engenders hate.”

“No, no,”…rising all his great height over me, [he answered:]

[We Socialists] do not preach hate; we preach love. We do not teach classes; we are opposed to classes. That is Capitalism again. There are classes now, and we say so. Why not? It’s true, terribly true. But it’s exactly that we are trying to beat. The struggle of the best men now is to rise from the working into the exploiting class. We teach the worker not to strive to rise out of his class; not to want to be an employer, but to stay with his fellow workers, and by striving all together, industrially, financially, politically, learn to cooperate for the common good of the working class to the end that some day we may abolish classes and have only workers—all kinds of workers, but all producers. Then we should have no class at all, should we? Only men and women and children.

“How are you Socialists going to get all this?”

[Said Debs:]

We Socialists aren’t going to get it. It’s coming out of the natural evolution of society, and the trusts are doing more toward it than we. Socialists are only preparing the minds of men for it, like the labor unions. They are taking the egotism out of men; subordinating the good of the individual to that of the union; and teaching self-sacrifice and service.

So with us. The party is the thing. It is governed by its members, who must pay to belong to it, and all perform services besides. They work, write, speak—what they can. But it’s theirs, our party is. They elect officers, and delegates; they nominate tickets; and they are taught to vote a straight party vote, no matter how hopeless the contest. That’s often a sacrifice of the present for the future, of the individual for society. But isn’t that good? That’s discipline. It’s an education in cooperation. Their reward will come when, by and by, we shall have everywhere, as we have here in Wisconsin now, a minority in office of representatives trained in that school, enlightened as to general economic and moral principles, and inspired with an ideal that is as fine as any religion in the world ever had—the good of all.

“That’s slow,” I said, “and you, Debs, are impatient.”

FOUNDATION LOVE OF MAN FOR MAN

[He said:]

Yes, I am in a hurry, but Socialism isn’t. Socialism is the most patient of reforms, but also it is the surest, and the truest. For we believe in man and in the possibility of the love of man for man. We know that economic conditions determine man’s conduct toward man, and that so long as he must fight him for a job or a fortune, he cannot love his neighbor. Christianity is impossible under Capitalism. Under Socialism it will be natural. For a human being loves love and he loves to love. It is hate that is unnatural. Love is implanted deep in our hearts, and when things are rearranged so that I can help my fellow man best by helping myself, by developing all my skill and strength and character to the full, why, then, I shall love him more than ever; and if we compete it will be as artists do, and all good men, in skill, productiveness, and good works.

———-

[Paragraph breaks added.]

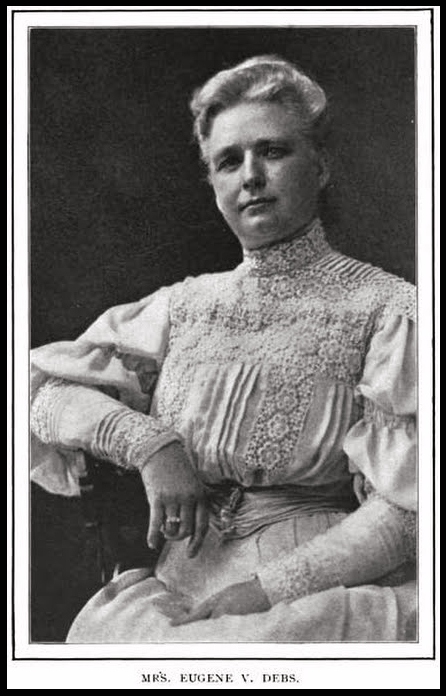

Note: although Mrs. Eugene Debs was not mentioned in article, the following photograph of Katherine (Kate) Metzel Debs was included.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

Everybody’s Magazine, Vol 19

(New York, New York)

-July-Dec 1908

https://books.google.com/books?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ

Oct 1908 – Vol 19, No 4

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA433

EVD by L. Steffens

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA455

Part II-“Socialists know what the matter is.”

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA462

See also:

Hellraisers Journal, Sunday October 4, 1908

Lincoln Steffens Interviews Eugene Debs, Part I

Lincoln Steffens

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lincoln_Steffens

The Bending Cross

A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs

by Ray Ginger

Introduction by Mike Davis

Haymarket Books, 2007

https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/839-the-bending-cross

See: Bending Cross by Ray Ginger, bottom of page 270-271:

http://ouleft.org/wp-content/uploads/TheBendingCross_BiographyofDebs.pdf

According to Ginger, the interview of Debs by Steffens occurred following a speech by Debs given July 12, 1908, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin:

By July 12 [1908] Debs was in Milwaukee, speaking to twenty-five thousand persons who paid admission to a Socialist picnic. Mingling with the audience was the celebrated journalist, Lincoln Steffens, who was writing a series of articles about the Presidential candidates…

When Eugene Debs had finally escaped from his admirers he was interviewed by Steffens at Victor Berger’s home…

For more on Katherine Metzel Debs:

Gentle Rebel: Letters of Eugene V. Debs

-ed by J. Robert Constantine

University of Illinois Press, 1995

(search: “Katherine Metzel Debs”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=P3Sse5ftltoC

The Socialist Woman

[Later-The Coming Nation]

-March-Dec 1908

https://books.google.com/books?id=OvM4AQAAMAAJ

October 1908, Girard, Kansas

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=OvM4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA3-PA1

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=OvM4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA3-PA2

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Commonwealth of Toil – Pete Seeger

Lyric by Ralph Chaplin

https://archive.org/stream/whenleavescomeou00chapiala#page/4/mode/1up