Old John Brown set an example of moral courage

and of single-hearted devotion to an ideal

for all men and for all ages.

-Eugene Victor Debs

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday October 4, 1908

Milwaukee, Wisconsin – Lincoln Steffens Interviews Eugene Debs

From Everybody’s Magazine of October 1908:

Part I:

—–

EDITOR’S NOTE.-“I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness,” said John the Baptist, when they questioned his mission. And his was the voice of promise of a new order of things. This voice of promise has come down the ages, sometimes almost stilled, again rising into tones of thunder. But always it has been a call to the poor and the unhappy-to the “rabble.” Unworthy mouth-pieces that voice has had, and blatant. But, for weal or for woe, whenever and wherever it has reached its full volume no earthly power has been able to drown its insistent cry. Is that voice to-day rising toward its highest note? Or do we hear merely the droning of false creeds? The voice of established order sounds clear and seemingly strong. But in Europe the cry of Socialism (they say it is applied Christianity) already bids fair to become dominant. In America more than a million thrill at its call. Debs is their voice. Fanatic or prophet? Inspired or insane? Only time will tell. But, for weal or for woe, we must listen. Debs believes that he voices the cry of a people wronged, and he believes he has the remedy for that wrong. For this reason we have asked him to talk to you. If he is a public enemy, you have here the chance to be come forearmed by being forewarned. We present you his gospel.

ALL radicals have programs. They differ radically among themselves. They cannot, therefore, all have “the” program of God and man which each one thinks his is. Not one of them may be sound, reasonable, desirable, or right. They may all be impossible. But, at least, they are programs, not merely platforms, Therefore they concern us.

For want to know what the causes are of our American corruption, and the cure. We have asked the leaders of the two old parties, and, excepting La Follette, they said, or they showed, that they didn’t really know. Socialists, with other radicals, are sure they do know. So we will let them tell us what they think the matter is and what they think we ought to do about it.

The President, Taft, and John Johnson don’t believe there is any “it”; they set aside the suggestion that most of our greater evils are traceable to a few fundamental, removable causes. There’s the money question and the tariff issue; the regulation of railroads, trusts, and criminals. They recognize seriously, though separately, these problems of business and money. Not so the problems of men and women: labor, poverty, crime. As the old political parties of Europe did so long, ours deny or ignore the social problem. The Socialists (whence the name) not only recognize, they offer a solution for it. Therefore Socialism grows.

For there is a social problem, and men find it out. The schools don’t teach it; the churches don’t preach it; the press won’t mention it; and, brought up, as we are, to mind our own business, we become too absorbed in that to pay much attention to our public business. But when the railroad magnate discovers that, to make his property pay, he must corrupt politics, and that, having done so, he is first honored, then disgraced, he learns that there is something wrong somewhere. And when the willing worker out of work sees the market glutted with goods he and his family need but cannot buy, he, also, realizes that there are problems of humanity, as well as of money, in a money panic. The “bum,” who is often an ex-child laborer, and the shop-girl who ekes out a living by taking a “gentleman friend”—they feel it vaguely. And I, going about from city to city and from state to state, and finding everywhere much the same conditions, due to essentially the same forces, operated by all sorts of men using similar methods for one everlasting purpose and to one identical end, I, slowly, reluctantly, am convinced that we all are facing some one great common problem.

And we are. There is some relation between the unhappy capitalist facing the prison bars and the miserable workman staring into the shop window. There is some causal connection between the man and the money that are out of employment. And the trust, the railroad rebate, the bribed legislator, the red-light dive, and the working-girl gone wrong form a living chain that can, and shall, be broken.

This is the problem of society as a whole, and as men find it out in fear and doubt, they look first to their old leaders; not for a final solution; all they ask is some recognition of it, some word of interest, comfort, hope. But when, seeing Congress passing an emergency currency bill to help money in distress, the unemployed assemble to exhibit their needs and “are given the stick”; when, watching Capital forming trusts and combines, Labor organizes unions and, asking relief from a power the courts have abused, gets an ambiguous anti-injunction plank; when, asking where they can find work, men hear that “God knows”; then, slowly, reluctantly, but naturally, they turn to the agitator on the street corner. He says he knows, and he makes it all plain; too plain, perhaps; but at least he understands the troubles of all those that are weary and heavy-laden, and he says he will give them rest. Is it any wonder they go to him, as they do?

The Socialists more than double their number every four years in the United States, and in Europe they did so till now they have in every parliament a strong, disciplined, uncompromising minority which seeks reform, not office; the Socialist leaders that have accepted seats in cabinets have been read out of their party. No, this remarkable international organization stands there compact and keen, demanding, amending, debating, and reporting back to the people. And that counts. The Socialist party is dictating policies to all the first-class governments abroad. Holding up its own menacing program in one hand and pointing with the other at its ever-growing vote, it is compelling the old parties to attempt social, not alone financial and political, reforms.

“We had to take up social reforms,” said the prime minister of England, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, just before he died, to an American friend of mine. “Germany was driven to them long ago; France, Italy, Austria, Holland, Belgium, and, finally, we English, all had to follow. And you, in the States, you cannot continue to ignore the demand. It becomes more and more pressing all the time, you know, and the radicals take advantage of every denial of it.”

Of course they do. The radicals are themselves evidences of the growing consciousness of a common, as well as an individual, problem of civilized living; and, as between the leadership that denies and that which acknowledges it, the majority of men (with the suffrage, now, remember) are bound either to sink into animal contentment or to follow radicals, like the Socialists, who not only recognize, but rejoice in, the work to be done; and, burning with their faith, offer not only hope, but something for every man to do; and not only a way out, but—a heaven on earth. Absurd? Maybe it is, but don’t I illustrate my own point? I’m looking for light, and I don’t care where I get it. If I don’t find it in one place, I’ll try another; if the Republicans and the Democrats shed only gloom, I’ll apply to the Socialists; if my old leaders say there is no light—why, then, I’ll have to ask Debs.

[Debs, Keeper of Socialist Heaven]

Yes, Eugene V. Debs is the keeper of the Socialist heaven. Locomotive fireman; labor agitator; strike leader; he was jailed once, and the Socialists, who take advantage of the misery of men to win them over, converted Debs in his cell at Woodstock. And now he is the leader of the Socialist party. I must confess that I didn’t want to take my Socialism from Debs. Having use only for the truth, not the excesses and fallacies, of Socialism, I desired to get the best possible view of it, so I had picked out another man to interview, a hard-headed, intellectual student. But if the Socialists preferred Debs, the “undesirable citizen,” “the incendiary,” who wrote: “Rouse ye, Slaves,” and called for a mob to follow him to Idaho, why, I felt that in a sense it was their party, not mine. And so, when they nominated him (the third time) for president of the United States, I saw Debs.

I don’t know how to give you my impression of this man; I suppose I can’t; I can hardly credit it myself, and I wouldn’t, I guess, if I hadn’t discovered so often before that the world (in the French phrase, “all the world”) hates a lover of the world. And that’s what ‘Gene Debs is: the kindest, foolishest, most courageous lover of man in the world. Nor am I the only one that thinks so. Horace Traubel says:

Debs has ten hopes to your one hope. He has ten loves to your one love. You think he is a preacher of hate. He is only a preacher of men. When Debs speaks a harsh word it is wet with tears.

And there’s James Whitcomb Riley, the Hoosier poet, he sez:

And there’s ‘Gene Debs—a man ‘at stands

And jest holds out in his two hands

As warm a heart as ever beat

Betwixt here and the Jedgment Seat.That’s a true, and an essential, description.

I met Debs at a Milwaukee Socialist picnic (25,000 paid admissions) where he was to speak, and, as he came toward me with his two hands out, I felt, through all my prejudice, that those hands held as warm a heart as ever beat. Warm for me, you understand, a stranger; and not alone for me: those two warm hands went out to all in the same way: the workers, their wives, their children; especially the children, who spring at sight right into Debs’s arms. It’s wonderful, really. And when, piloted, plucked at, through the jammed mass of waiting humanity, he went upon the platform to speak, he held out his handfuls of affection to the crowd. He scolded them.

[He said:]

Men are beginning to have minds; some of you don’t know it.

There was nothing demagogic about that speech. It was impassioned, but orderly; radical, but (granting the premises) logically reasoned. It was an analysis of the platforms and performances of the two old parties to show that they would do for Business as much as they dared and for Labor as little; and the conclusion was an appeal to the workers—not to vote for Debs; “I don’t ask that,” he said, and sincerely, too.

All I ask is that you think, organize, and go into politics for yourselves.

Delivered from a crouching attitude, with reaching hands and the sweat dripping from head and face, the speech fairly flew, smooth, correct, and truly eloquent. Debs is an orator.

[Wrote Eugene Field:]

If Debs were a priest, the world would listen to his eloquence, and that gentle, musical voice and sad, sweet smile of his would soften the hardest heart.

Half the world does listen to Debs, and his eloquence does soften its heart. But it wasn’t art that kept that Milwaukee crowd steaming out there in the sun and, at the close, drew it crushing down upon the orator. And it wasn’t what he said, either; too much of the gratitude was expressed in foreign tongues. It was the feeling he conveys that he feels for his fellow men; as he does, desperately.

Debs is dangerous; it is instinct that makes one half of the world hate him; but don’t. He loves mankind too much to be hurt of men; and that’s the power in him; and that’s the danger. The trouble with Debs is that he puts the happiness of the race above everything else: business, prosperity, property. Remarking this to him, I said lightly that he was, therefore, unfit to be president.

[He answered seriously:]

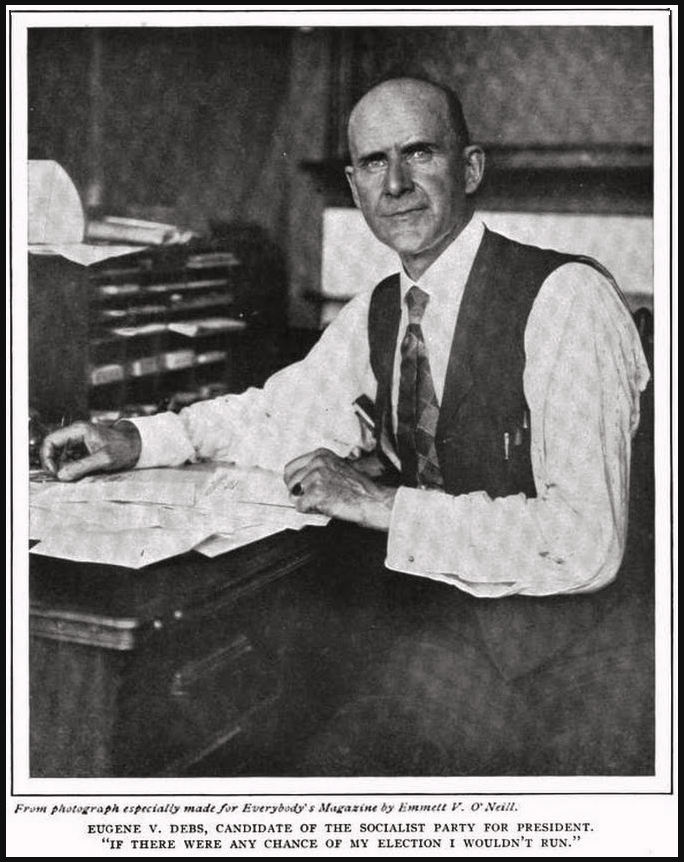

Yes, I am not fitted either by temperament or by taste for the office, and if there were any chance of my election I wouldn’t run. The party wouldn’t let me. We Socialists don’t consider individuals, you know; only the good of all. But we aren’t playing to win; not yet. We want a majority of Socialists, not of votes. There would be no use getting into power with a people that did not understand; with a lot of office-holders undisciplined by service in the party; unpurged, by personal sacrifice, of the selfish spirit of the present system. We shall be a minority party first, and the cooperative commonwealth can come only when the people know enough to want to work together, and when, by working together to win, they have developed a common sense of common service, and a drilled-in capacity for mutual living and cooperative labor.

I am running for president to serve a very humble purpose: to teach social consciousness and to ask men to sacrifice the present for the future, to “throw away their votes” to mark the rising tide of protest and build up a party that will represent them. When Socialism is on the verge of success, the party will nominate an able executive and a clear-headed administrator; not—not Debs.

[“It may be deemed expedient to hang Debs some day…”]

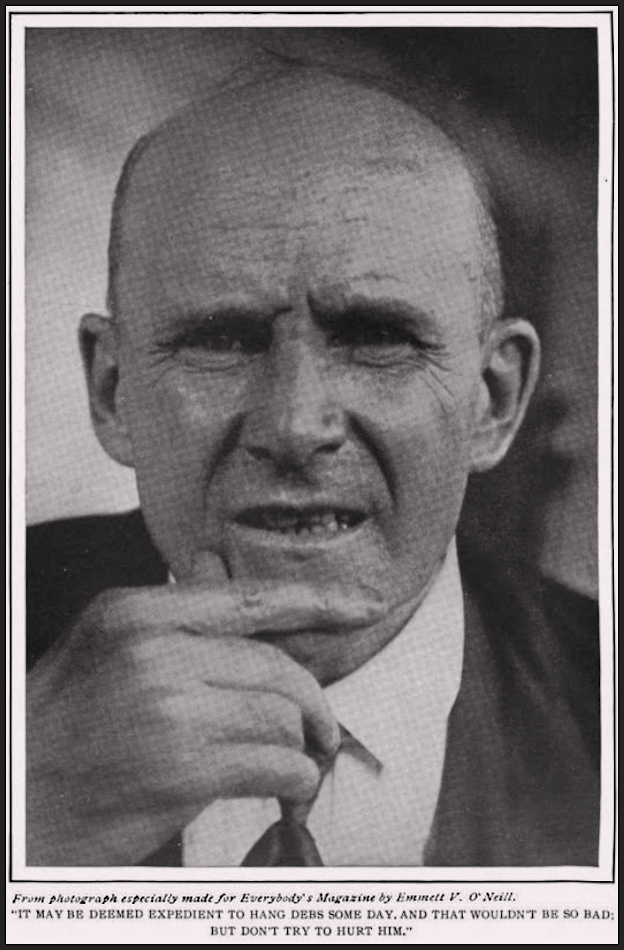

It may be deemed expedient to hang Debs some day, and that wouldn’t be so bad; but don’t try to hurt him. In the first place, it’s no use. Nature has provided for him, as she provides for other sensitive things, a guard; she has surrounded Debs with a circle of friends who go everywhere with him, shielding, caring for, adoring him. They sat all through my interview, ready to accept what I might reject. So he gets back the affection he gives, and no strange hate can hurt him. It can hurt only the haters. And as for the hanging, he half expects that.

[Debs on “Arouse Ye Slaves”]

“How could you,” I asked, “thinking as you do that Socialists must learn by party service and personal sacrifice to deserve power, how could you have put out that call for a mob to rescue Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone?”

[He answered:]

Oh, that, the “Rouse ye, Slaves”? Why, my God, man, that was only a cry. That was pain. You know Colorado-

Yes, I know Colorado. I know that there was, that there is now, and that it is planned that there shall be, no justice in that state; know it, too, from the unjust themselves. “But,” I urged, “the folly of mob force.”

“True,” said Debs, hanging his head. ” It was folly, but,” he added, looking up as if frightened, “do you know, I sometimes think I am destined to do some wild and foolish, useless thing like that and—so go.” Debs has written much about John Brown. Socialists see the repetitions of history, they read it in parallels, and they have found in it heroes of their own. Debs’s hero is John Brown.

[Debs on John Brown]

“The most picturesque character, the bravest man, the most self-sacrificing soul in American history was hanged at Charlestown, Virginia, December 2, 1859.” Thus Debs begins an article which fairly worships John Brown’s “moral courage and single-hearted devotion to an ideal for all men and for all ages. He resolved,” says Debs, “to lay his life on Freedom’s altar and to face the world alone. How perfectly sublime!”

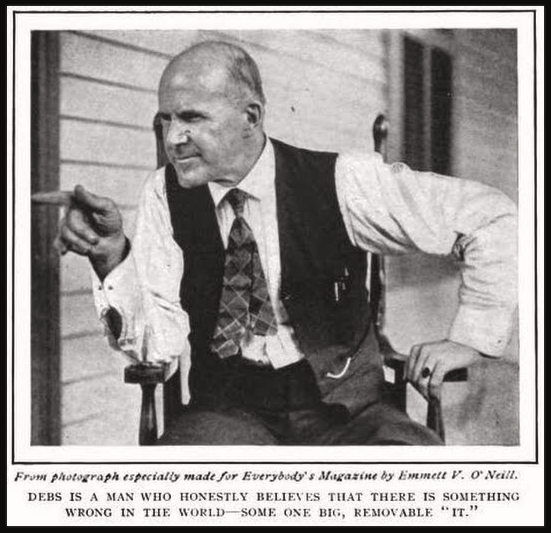

That’s Debs, I suspect. His adoration of John Brown is a view into himself. It gives us the ideal and the dread; the use and the danger; the strength and the weakness of the man. One must allow for personality in an interview, and in this case we should not forget for one moment that we are dealing with a man who speaks and acts from his heart, not his head; who honestly believes that there is something wrong in the world—some one big, removable “it,” which meanwhile works terrible injustice to his kind of people, and who, therefore, feels that he may do “some wild and foolish, useless thing like”—John Brown.

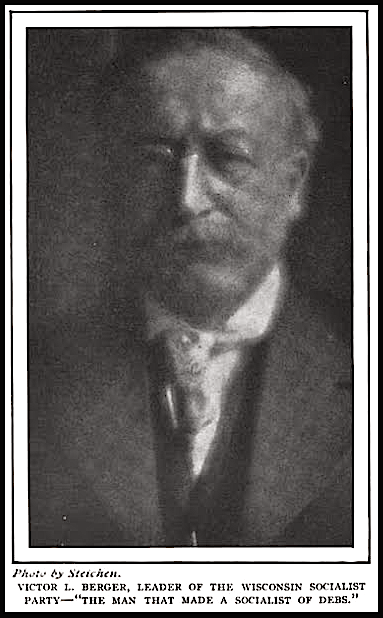

[Victor Berger]

I had a foil for Debs, however. The interview proper was at the house of Victor L. Berger, “the bear”; leader of the Wisconsin Socialist party, which has forceful minorities in the state legislature and the Milwaukee city council. Berger is the man that made a Socialist of Debs, and the teacher, a most aggressive personality, took a most aggressive part in his pupil’s interview, which was fortunate. For Socialism seems to be a science. It is an interpretation of history; a theory of the evolution of society; no mere, man-dreamed Utopia, as I have thought, but a faith, a calculation that, since the economic forces which have brought man from savagery up to the present state of civilization are continuous, we can foresee the next inevitable step. But it takes no little study of economics and much reading in the mass of Socialist literature to speak with authority on the subject, and Berger—with a library coveted by the University of Wisconsin—is an acknowledged authority.

[Said Debs (for example):]

We believe that Socialism would come without the Socialists.

“Ach,” said Berger, with his strong German roll, “we know it. Can’t we see it?”

[Said Debs:]

Yes, the trusts are wiping out the competitive system. They are a stage in the process of evolution: the individual; the firm; the corporation; the trust; and so, finally, the commonwealth. By killing competition and training men to work together, trusts are preparing for the cooperative stage of industry: Socialism.

“Then you would keep the trusts we have and welcome others?” I asked.

“Of course,” he answered, and Berger nodded approval.

“They do harm now,” I suggested.

“Yes,” said Debs, but Berger boomed: “No; not the trusts. Private owners of the trusts do harm, yes; but not the trusts.”

“Well, but how would you deal with the harm?”

“Remove ’em,” snapped Berger, and Debs explained:

We would have the government take the trusts and remove the men who own or control them: the Morgans and Rockefellers, who exploit; and the stock holders who draw unearned dividends from them.

“Would you pay for or just take them?”

Berger seemed to have anticipated this question. He was on his feet, and he uttered a warning for Debs—in vain.

“Take them,” Debs answered.

“No,” cried Berger, and, running around to Debs, he stood menacingly over him. “No, you wouldn’t,” he declared. “Not if I was there. And you shall not say it for the party. It is my party as much as it is your party, and I answer that we would offer to pay.”

It was a tense but an illuminating moment. The difference is typical and temperamental; and not only as between these two opposite individualities, but among Socialists generally. Debs, the revolutionist, argued gently that, since the system under which private monopolies had grown up was unjust, there should be no compromise with it. Berger, the evolutionist, replied angrily that it was not alone a matter of justice, but of “tactic”; and that tactics were settled by authority of the party.

“We (Socialists) are the inheritors of a civilization,” he proclaimed, “and all that is good in it—art, music, institutions, buildings, public works, character, the sense of right and wrong—not one of these shall be lost. And violence, like that, would lose us much.” Berger cited the Civil War: “All men can see now that it was coming years before 1861. Some tried to avert it then by proposing to pay for the slaves. The fanatics on both sides refused. We all know the result: slavery was abolished. But how? Instead of a peaceful evolution and an outlay of, say, a billion, it was abolished by a war which cost us nearly ten billion dollars and a million lives. We ought to learn from history, so I say we will offer compensation; because it seems just to present-day thought and will prove the easiest, cheapest way in the end. And anyhow,” he concluded, “and besides, the party, it has decided that we shall offer to pay.”

And Berger was orthodox. Looking up the point afterward, I found that the “authorities” are on his side; the party will offer compensation for property taken by eminent domain.

“Deps?” said Berger. “Deps, with the soft heart—Deps is the orator.” And he meant “only” an orator. Berger loves his pupil’s “soft heart,” but he loves Socialism more, and so during the interview, while Debs was trying to convert me, “the bear” was intent upon the orthodoxy of my report; and while Debs’s other friends sat close up around him, under the light of the lamp, to protect the man, Berger hovered about in the shadow, anxious, on guard, to protect—”the cause.”

[Part I of II.]

[Paragraph breaks added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

Everybody’s Magazine, Vol 19

(New York, New York)

-July-Dec 1908

https://books.google.com/books?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ

Oct 1908 – Vol 19, No 4

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA433

EVD by L. Steffens

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=h2cXAQAAIAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA455

See also:

“Arouse, ye slaves! by EVD

From Appeal to Reason of March 10, 1906

https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1906/arouse.htm

“John Brown: History’s Greatest Hero”

-by Eugene Debs

From the Appeal to Reason, November 23, 1907

https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1907/johnbrown.htm

Victor Berger

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_L._Berger

Tag: Debs Campaign 1908

https://weneverforget.org/tag/debs-campaign-1908/

Debs:

His Life, Writings and Speeches

With a Department of Appreciations

-Authorized

The Appeal to Reason, 1908

https://archive.org/stream/cu31924002385379#page/n7/mode/2up

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=4qs9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP5

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We Have Fed You All For A Thousand Years – Bruce Brackney