—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday April 4, 1912

Lawrence Textile Strikers Win Great Victory with I. W. W., Part II of IV

From the International Socialist Review of April 1912:

ONE BIG UNION WINS

By LESLIE H. MARCY and FREDERICK SUMNER BOYD

On January 11, anticipating some difficulty on pay day, the Secretary of Local 20, I. W. W. wired to Joseph J. Ettor, member of the National Executive Board, who was then in New York City, to go to Lawrence. He left the next afternoon, and arrived on the night of January 12.

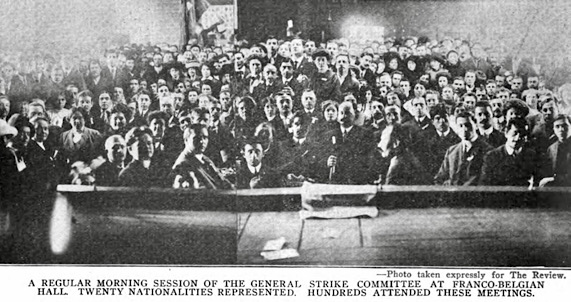

Plans were then laid for the conduct of the strike. A general strike committee was formed that met daily, each nationality on strike being represented on it by three delegates. In addition there were three representatives each from the perchers, menders and burlers, the warp dressers, Kunhardt’s mill, the Oswoco mill, the paper mill, the workers in which had struck in sympathy with the textile workers and presented similar demands, and from time to time other sections were represented that were gradually merged as occasion demanded. The general strike committee thus numbered 56 men and women, all of them mill workers.

The first work of the committee was to devise means for carrying on the fight and caring for the strikers. There were no funds when the strike was declared, but in a week or ten days money began to dribble in from surrounding New England towns, and as the strike continued contributions came in from every State in the Union, from all parts of Canada and even from England.

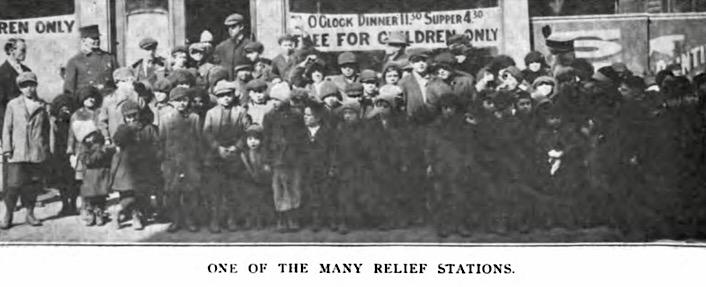

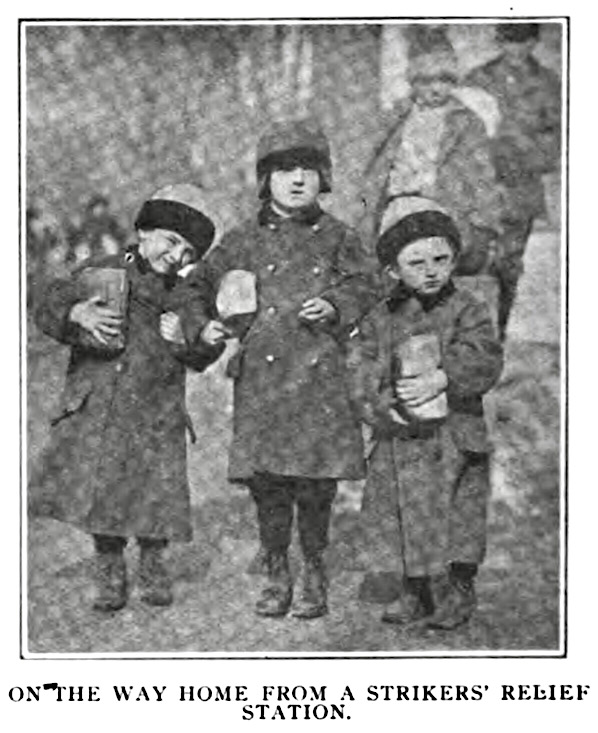

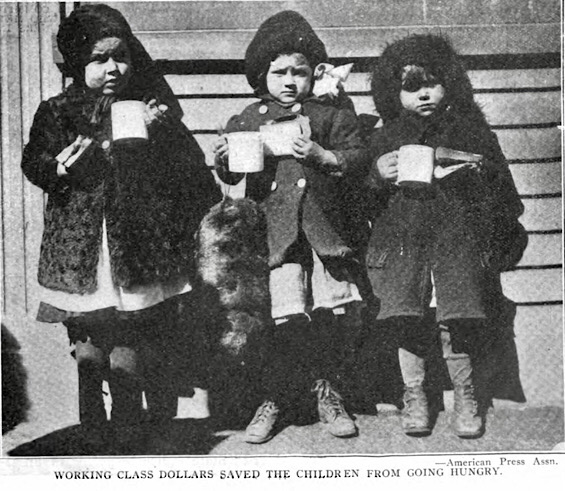

The money in the shape of strike pay would not have lasted a week, but this battle was conducted on a different basis from former fights. Each nationality opened relief stations and soup kitchens, and was responsible for the care of its own people. The Franco-Belgians had had a co-operative in operation long before the strike, and food purchases were made through its machinery. Money was paid over to the various national committees as it became necessary by the general finance committee, with Joseph Bedard as Financial Secretary. With this money the purchasing committee bought goods, and the national committees took their portion.

Meals were provided twice a day at the various stations for the strikers who needed them, and in this manner the Franco-Belgian station at the Mason street headquarters provided 1,850 meals twice daily, the Italians 3,500, the Syrians 1,200, Lithuanians 1,200, the Poles 1,000, and soon, the Germans took care of 150 families and several hundred single workers.

In addition to money, contributions of clothing of all sorts were forwarded to the city, and in particular the Syrians and Poles throughout the country rushed to the support of the strikers with carloads of food, quantities coming from as far west as Chicago.

It was currently reported that the strikers were starving. As a matter of fact no striker starved during the strike, and the vast majority of them were actually better cared for in the way of food and clothes during the strike than they were able to care for themselves while working in the mills.

Before leaving the matter of finance it is interesting to note that the experience with the A. F. of L. methods has led everybody to look for graft and plunder in labor union funds. This attitude in many quarters was the inevitable legacy that the I. W. W. had to inherit, and demands for a strict accounting soon began to come in from various quarters, and from many people, whether they were entitled to know or not.

Such demands were not granted save to those who were entitled to know. The condition of the war chest was a matter of supreme interest to the bosses, and had to be kept from them. Efforts were made to find out, and Judge Leveroni of Boston, without a shadow of right, demanded an investigation. When the judge’s action became known, contributions were accompanied with requests from hundreds of contributors that no information on the subject be published until after the strike and then only to contributors.

The funds have been contributed mainly by Socialists, who sent about $40,000, I. W. W. locals and others, about $16,000, and A. F. of L. local unions about $11,000, the last named contributing despite the bitter official antagonism of the A. F. of L.

The conduct of the strike and the policy pursued rested in the hands of the general strike committee. At the outset all meetings of the committee were public and were maintained public throughout. There was no secrecy, and no plotting. The city was filled with Pinkerton, Burns and Callahan agents, and they found nothing to do. They attended the strike committee meetings, as did any other individual who was interested in the proceedings. The completest democracy was maintained, delegates reporting on matters concerning their own section. The reports would go something like this:

Lettish is all right. Same now as before. Have few scabs, others stand firm till strike settle.

Jews have a few scabs, but they were born scabs. Can’t get them out, but all others firm.

Franco-Belgian have some scabs. Two Portugese fellows working in weave room of Pacific. Then French fellows get in and make another strike and scabs chased out. Franco-Belgians all stand together.

Reports would be speedily acted upon, and then came reports of special committees, correspondence, unfinished business and good and well fare. The meetings were most inspiring and enthusiastic. Unity of purpose prevailed, and there was at no time the faintest suggestion of national feeling.

Usually the proceedings finished with the singing of the Internationale and cheers for the strike and the I. W. W.

The committee was presided over by Ettor until he was jailed, and from then on by Haywood, William Yates acting on the occasions when Haywood was away from the city addressing meetings and getting funds. The committee met at 10 or 10:30 a. m. From 5 to 7 a. m. the strikers were out on the line, and a new method of picketing was evolved.

Soldiers’ bayonets and policemen’s clubs had been used from the first to prevent picketing, and the necessity produced what came to be known as the “endless chain.” All the mills but one, the Arlington, lay on the east side of Essex street, and this side of the street was barred to pickets absolutely. But the scabs had to come down streets leading into Essex street, and on the West side from 5,000 to 20,000 pickets massed every morning during the strike.

No one was allowed to stand still for a moment, so the thousands of pickets moved ceaselessly up and down Essex street and Broadway, on the South side of which was the big Arlington mill. It was an endless chain. The sidewalk was black with pickets, each wearing the I. W. W. badge or button, and a label, consisting of pasteboard attached to a piece of scarlet cloth, bearing the words “Don’t be a scab,” or “I am not a scab.”

One of the most prominent figures in the picket line was Mrs. Annie Welzenbach, a young woman known throughout the city as being the most highly paid worker in the mills, earning $20 a week.

Everyone knew her, and her slogan every day during the strike was “Get out on the picket line.” She and her two sisters were dragged from their beds one night and thrown into jail.

Another well known picket was Josephine Liss, who testified in Washington as follows:

“Did you ever have any trouble with a soldier?” asked the chairman.

“I certainly did,” was the reply.

“Well tell us about it.”

[Said Miss Liss:]

I was out walking one Sunday morning, when I got near my home a soldier stopped me and told me to turn back. I refused to do so. He caught me by the arm and swore at me horribly. I struggled with him and he dropped his gun. I struck him in the face with my muff.

Several policemen and militiamen came up then. One of the policemen asked me my name and I refused to give it. I felt I had been insulted. The policemen said he had seen me at court during the trial of Mr. Ettor. When I went to court the next day I was arrested.

“What for?” asked Representative Stanley of Kentucky.

“For assaulting a soldier,” said Miss Liss, and her reply caused a ripple of laughter.

“When I was arrested I refused to pay the fine of $10 and appealed the case. They reduced my bail to $2.”

Threats were repeatedly made against Haywood, Yates, Trautman, Francis Miller and others, culminating in a murderous assault on James P. Thompson, when three thugs entered his bedroom, cut open his head with blackjacks, and fired at him three times. This outrage the police refused to investigate.

On the same day that Thompson was slugged State Police Inspector Flynn attempted to provoke Haywood, who was talking to Thompson as he lay in bed in the Needham Hotel. Flynn, accompanied by half a dozen strong arm men came into the room, and on seeing Haywood thrust his face close to his and menaced him with his fist, saying:

“Mr. Haywood, I hear you have been talking about me in your speeches. Just you understand that I won’t have you talking about me and take notice that anything you have to say must be said to my face. Do you hear?”

Haywood was wise to the game, and fortunately for Flynn and for some of his bulls controlled his temper and the episode closed.

An indication of the stress under which everybody worked, and the hourly expectation of arrest, is afforded in the action of the general strike committee after Ettor’s arrest, when at Haywood’s suggestion a duplicate committee was elected on the same basis of representation, the duplicate committee being present at all meetings and learning the routine and progress of the strike. This plan also brought a larger number of strikers in direct touch with the work at the central headquarters. There is little doubt that this action went far to checking the police in arresting strike leaders.

At the same time the funds were withdrawn from the banks, only enough being deposited to provide for two or three days ahead at any one time, the rest being distributed where it could be easily secured but out of reach of a court injunction, which was also hourly expected.

—————

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Lawrence Strike Committee, Drunk Cup to Dregs, Bst Dly Glb Eve p5, Jan 17, 1912

https://www.newspapers.com/image/430627498/

International Socialist Review

(Chicago, Illinois)

-April 1912, pages 613-30

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n10-apr-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bread and Roses from “Pride”