—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Monday September 4, 1922

Charles Town, West Virginia – Miners on Trial for Treason Against the State, Part II

From The North American Review of September 1922:

THE MINERS AND THE LAW OF TREASON

BY JAMES G. RANDALL

[Part II of II]

Turning to the case of the miners, we find that the offense for which they (or rather a selected number of them) are held is treason against the State of West Virginia. In the Constitution of the State of West Virginia there is the following provision:

Treason against the State shall consist only in levying war against it, or in adhering to its enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court. Treason shall be punished, according to the character of the acts committed, by the infliction of one or more of the penalties of death, imprisonment or fine, as may be prescribed by law.

It will be noticed that the provisions in the West Virginia Constitution resemble those of the Federal Constitution in the definition of the offense and the requirements as to evidence sustaining the overt act, but that the State Constitution goes farther than that of the United States in that it specifies the general nature of the punishment. An examination of the West Virginia code shows that the punishment, as further defined by the Legislature, shall be death, or, at the discretion of the jury, confinement in the penitentiary not less than three nor more than ten years and confiscation of the real and personal estate. Withholding knowledge of treason, attempting to justify armed insurrection by written or printed words, or engaging in an unlawful assemblage, are punishable by lesser penalties, thus indicating that these offenses are regarded as distinct from treason itself. As to what constitutes “levying war” against the State, this is largely a matter for interpretation by the court, and it appears that Judge Woods has made considerable use of Federal as well as State decisions in determining his rulings.

The acts for which the miners are on trial took place in connection with the serious outbreak of August, 1921. As a climax of years of growing hostility, during which the United Mine Workers had made repeated efforts to unionize the mine fields of Logan and Mingo counties, several hundred men assembled on August 20 at Marmet, West Virginia, with the intention of making some kind of demonstration or attack, the exact purpose of which is disputed. An important feature of the case is that the Governor had previously proclaimed martial law in Mingo County, and had sent State troops into that county to preserve order. It is the contention of the prosecution that the acts of the miners constituted a defiance of this martial law, and an intention to resist the troops.

An appeal by “Mother Jones”, a well-known leader among the miners, failed to disperse them, and the armed force, picturesquely uniformed in blue overalls and red bandanna handkerchiefs, proceeded on their march. The first violence occurred at Sharples in Boone County, where a small force of State police was resisted by the miners while seeking to serve warrants upon men wanted by the Logan County authorities. Several miners were killed and from this time the march assumed much more alarming proportions. By the time the Boone-Logan county line was reached the invaders numbered about eight thousand. Don Chafin, sheriff of Logan County, raised a defending force of approximately two thousand which he commanded until, after some delay, Governor Morgan commissioned Colonel Eubanks to take charge with State troops. For over a week the opposing “armies” confronted each other over an extended mountainous battle-front in the neighborhood of Blair, and there was considerable detached fighting. On the defending side three deputy sheriffs were killed, and it was for their deaths that the indictments for murder were drawn. Probably more than twenty of the invaders lost their lives.

Much of the trouble seems to have been due to the practice of employing in the non-union mining area great numbers of deputy sheriffs who were paid not from county funds but by the coal operators, and were referred to as “mine guards”. Professional gun men were also supposed to have been employed by the companies. It has been a matter of bitter comment that the prosecution in the treason trial was conducted not by the State attorneys but by the operators’ lawyers.

On the Governor’s request, President Harding issued a proclamation, reminiscent of the language of Washington again the whisky insurgents, warning the men to disperse, but as the warning was disregarded, about 2,000 Federal troops were actually sent to the scene of the trouble. Their presence reinforced the conciliatory negotiations conducted with the marchers by General Bandholtz through the union leaders, and brought about the prompt dissipation of the whole movement.

Indictments for treason and murder were brought by the Logan County Grand Jury, and 120 of the cases were removed to Jefferson County, a farming region on the eastern border of the State, remote from the mining district. When the trial opened on April 24, the first manœuver of the defense was to move to have the indictments quashed, and on this motion Judge Woods delivered an important ruling on April 25. The motion to quash was based upon two points: the omission of the word “feloniously” from the indictment, and the general vagueness of wording. On the first point Judge Woods said:

The position taken by the defendants is that…treason is a felony. In a sense, that is true. But still treason, in itself, is an offense of a particular kind and character and of a higher dignity than a mere felony. Treason is offense against the State, against the sovereignty of the State. All other crimes, while offenses against the State,…are yet primarily offenses against individuals….The proper word to describe the intent in treason is “traitorously”, and that word, I think, is sufficiently conclusive to include the whole criminal intent that is necessary to be alleged in an indictment for treason.

Judge Woods found greater difficulty in dealing with the second point in the demurrer-the vagueness of the indictment-and admitted that this matter had caused him some perplexity. He settled the matter temporarily by overruling the objection, adding that the same question might be presented later on motion in arrest of judgment.

“To destroy and nullify by force of arms, violence, murder and open warfare martial law in…Mingo County, ” “to release persons…legally arrested and incarcerated,” “to prevent the execution of the laws,” and “to deprive the people…of the protection afforded by the laws” in Logan and Mingo counties, “especially to destroy and nullify martial law in…Mingo County and to nullify the proclamation of the Chief Executive of the State”-these were the counts in the indictment which the defense objected to as vague and indefinite. After a full reasoning, Judge Woods concluded that the acts alleged fitted the counts of the indictment and he did not find any formal or substantial defects sufficient to overrule it.

In his ruling the judge called attention to those sections of the West Virginia code which deal with the calling out of State troops and with unlawful assemblages in resistance thereto. When the troops have been called out in the prescribed manner and under the proper circumstances to suppress a riot or tumult, and warning has been given for the assemblage to disperse, anyone who “willfully and intentionally fails to do so as soon as practicable is guilty of a felony, and shall on conviction be imprisoned in the penitentiary for not less than one nor more than two years.” If this provision of the code should be taken as applicable to the miners, then their guilt was felony, not treason under the statutes, and their penalty would be much lighter than if the treason charge should hold. It would still remain, however, for the courts to apply the constitutional definition of treason as superior to the code. “Any act that would constitute treason under the constitutional provision,” said Judge Woods, “would have to be pronounced treason by the courts, even though the Legislature might have pronounced it a different offense.”

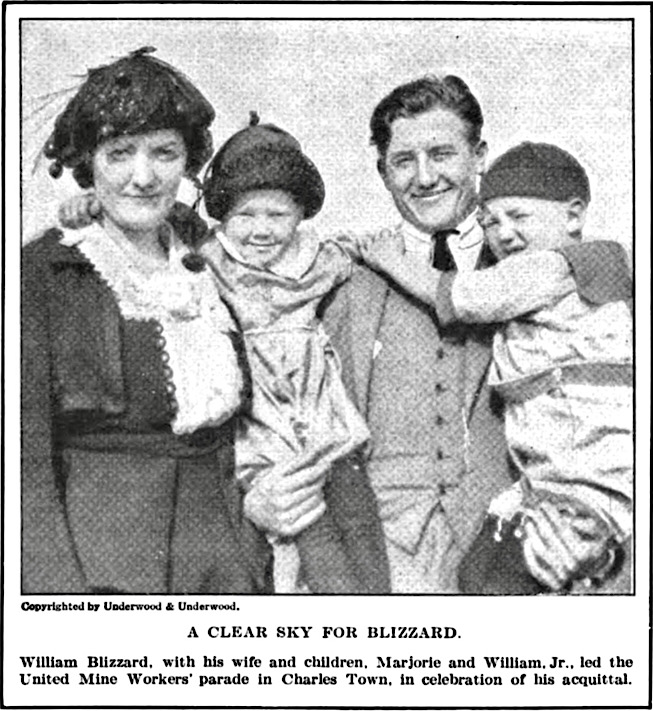

One phase of the controversy in which the defense scored a point was in obtaining a ruling that each defendant must be tried separately, and that for each defendant a bill of particulars must be filed, specifying the overt acts of each and the time and place of his connection with the alleged crimes. Besides prolonging and complicating the trial, this placed a heavy burden upon the State in the presentation of its evidence, since in a case where thousands joined in an armed march it was practically impossible to specify the overt act of each one. Proceeding on this plan of separate trials, the prosecution selected, as the first prisoner to be tried, William Blizzard, a local official of the Miners’ Union, a man who was not only a prominent organizer, but who figured as a leader on the armed march. The proceedings from that point consisted chiefly in the elaborate testimony of many witnesses concerning the details of the march and of Blizzard’s connection with it. Blizzard’s selection came as something of a surprise, since the expectation was that this distinction would be accorded to C. F. Keeney [Frank Keeney], president of the Mine Workers’ district organization [District 17], or to Fred Mooney, secretary of that organization.

Relying upon the doctrine that “in treason all are principals”, the State sought to prove that an overt act was committed, and contended that all who participated in the conspiracy were traitors in the full sense. On this point John Marshall wrote as follows in the famous Bollman and Swartwout case:

It is not the intention of the court to say that no individual can be guilty of this crime who has not appeared in arms against his country. On the contrary, if war be actually levied, that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose, all those persons who perform any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors. (4 Cranch, 75, 126.)

It is true that Marshall resorted to some rather ingenious “explaining” in reconciling this doctrine with the Burr decision, but there was no real inconsistency, since in the case of Burr no levying of war was actually proved, and it was for this reason that the collateral evidence connecting Burr with the assemblage on the island was excluded, and not because such evidence was fundamentally irrelevant. The doctrine of the Bollman case as to the equal criminality of accessories and principals in case the overt act is proved still holds good.

The Blizzard trial consumed a month and developed a striking diversity between the two sides, not only as to legal contentions but as to the facts as well. Attorneys for the prosecution contended that the miners’ march was more than murder, more than an unlawful assemblage, that it was war waged to destroy the sovereignty of the State, and that the very life of the State itself was at stake. They sought to show that Blizzard participated in every part of the movement, that he addressed the miners before the march, led several hundred marchers, procured ammunition, and in general stood out as the man having greatest authority. Being required by the court to select which overt act it would rely upon for conviction, and being forced to select some act performed in Logan County where alone the court in which the defendant was indicted could have jurisdiction, the State announced that it would rely upon the presence of the defendant with the armed marchers in Logan County.

The defense maintained that the march was intended to make a peaceable demonstration, that the purpose was in no way treasonable, that no assault upon the Logan jail or the sheriff was intended, that the men were moved by a desire to protect their homes against thugs whom they understood to have been employed by their opponents, and that without the aggression of the State police there need have been no bloodshed. As to Blizzard’s activities, witnesses for the defense testified that during all the time of the march and the fighting he was in District 17 headquarters at Charles Town [Charleston], and that he only went into Logan County at the request of General Bandholtz to induce the miners to turn back.

When the prosecution had finished its testimony, Blizzard’s attorneys made an interesting manœuver. Contending that the State had failed to offer evidence sufficient for the jury’s consideration, they presented a motion to strike out the evidence and direct a verdict of acquittal. Judge Woods overruled the motion in an opinion which contained a significant passage on the general subject of State treason. The defense had contended that under our dual form of government there can be no such thing as treason against a State. The judge pointed out that the Federal Constitution itself recognizes the crime of treason against a State in that clause which provides for the rendition of any person charged with “treason, felony or other crime” (against the laws of the State) who may have fled to another State.

The State Governments, he argued, parted with only a portion of their sovereignty upon entering the Union under the Constitution. They remain in possession of all the great police powers, and they control those domestic matters which concern the people directly, including the protection of persons and property against violence. He continued:

If we can imagine such a thing as the total destruction of the State Government,…we would picture to ourselves a condition…far more calamitous to the people of that State than would be the condition of the whole country if the Federal Government should be abandoned….Anarchy would follow the destruction of the State Government, but not of the Federal Government. The State has citizens and is under the obligation to protect them in all their rights; it is under the obligation of punishing those who infringe on their rights….Every citizen of the State owes…loyalty and allegiance. It would be a strange condition indeed if that Government should be vested with all the authority and power necessary to protect every individual within its borders, and yet be denied power to protect its own life.

Turning to the question as to whether the State’s evidence was such as is proper to support an indictment for treason, the judge held that levying war does not necessarily imply a purpose to destroy the Government, but if there is an effort to coerce the Government by force of arms, and make the Government yield for any special object to the will of those who exert such force, that would be war against the State and would be treason.

On May 27 the initial case in the miners’ docket was terminated by the acquittal of Blizzard. Further treason proceedings were then postponed while the court proceeded with the murder cases. Once again the difficulty of obtaining in this country a conviction for the grave offense of treason has been made evident. Whatever may be the legal refinements of the subject, treason to a jury means a determined, forcible defiance of the Government, involving a real menace to organized society, and the tendency of American juries to take a liberal and sympathetic view toward what may be called “near treason” seems now so well confirmed that convictions are to be expected only in the clearest and most extreme cases.

James G. Randall.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote Fred Mooney, Mingo Co Gunthugs, UMWJ p15, Dec 1, 1920

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=2hg5AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA23-PA14

The North American Review

(Concord, New Hampshire)

-Sept 1922

“The Miners and the Law of Treason” by James G. Randall

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.20482835&view=2up&seq=322

https://archive.org/details/jstor-25112811/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater

https://books.google.com/books?id=T00AAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=randall&f=false

IMAGE

Billy Blizzard and Family, Lt Dg p14, June 17, 1922

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015028101460&view=1up&seq=1006&skin=2021

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From The North American Review:

“The Miners and the Law of Treason” by James G. Randall, Part I

Ex parte Bollman, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 75 (1807),

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ex_parte_Bollman

Tag: Battle of Blair Mountain 1921

https://weneverforget.org/tag/battle-of-blair-mountain-1921/

Tag: West Virginia Miners March Trials 1921-1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/west-virginia-miners-march-trials-1921-1922/

Tag: Billy Blizzard Treason Trial 1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/billy-blizzard-treason-trial-1922/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Battle of Blair Mountain – Louise Mosrie