—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday September 3, 1922

Charles Town, West Virginia – Miners on Trial for Treason Against the State, Part I

From The North American Review of September 1922:

THE MINERS AND THE LAW OF TREASON

BY JAMES G. RANDALL

[Part I of II]

Once again the quiet village of Charles Town, West Virginia, in the historic Shenandoah valley, has furnished the setting for a memorable State trial. As in 1859, when John Brown went to the gallows for a traitorous assault which was misconceived as a stroke for Abolition, so in the present year the eyes of the nation have been focused upon this same little county seat while hundreds of miners have faced trial on indictments for murder and treason in connection with the “insurrection” of August, 1921. Twenty-four of the miners who were associated with the armed march of several thousand men directed against the coal fields of Logan and Mingo counties have been charged with the grave offense of “treason”, and it is with this phase of the question that the present article proposes to deal. Many circumstances unite to make the trials notable. The long continued efforts of the United Mine Workers to unionize the West Virginia fields, the elaborate litigation which included several federal injunction suits, the huge scale as well as the gravity of the indictments, the intensity of the industrial disputes involved, and the challenge to the State authorities to uphold elemental social order and yet deal fairly with both sides in an unusually bitter struggle-all these factors lift the case above the level of an ordinary criminal proceeding. Without attempting, however, to discuss the industrial phases of the “miners’ war”, the writer proposes to view the cases from a restricted angle and to consider their relation to the history of treason in our legal system.

Though the charge against the miners is the rara avis of treason against a State, the analogy of this crime with treason against the United States is very close, and it may therefore be useful to recall some of the outstanding points in the history of national treason. Treason is the only crime which the Federal Constitution undertakes to define. It consists “only in levying war against the United States or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort”. To prove treason, the commission of an overt act must be established by at least two witnesses, unless there is a confession in open court. Congress has no authority to fix the nature of the crime, and can neither enlarge nor restrict the offense beyond the constitutional definition. Congress may, however, fix the punishment, and among the acts passed by the first Congress ever assembled under the Constitution was the Treason Law of 1790, which established the penalty of death for this highest of crimes.

In the course of time a well recognized body of principles has grown up around the law of treason. Thus it is recognized that “constructive treason” has no place in our legal system. There must be an actual levying of war. A mere plotting, gathering of arms, or assemblage of men is not treason, in case no overt act is committed. The “levying war”, however, has been rather broadly defined by our courts. Besides formal or declared war, it includes an insurrection or combination which forcibly opposes the Government or resists the execution of its laws. Engaging in an insurrection to prevent the execution of a law is treason, because this act amounts to levying war. The mere uttering of words of treasonable import does not constitute the crime, nor is mere sympathy with the enemy sufficient to warrant conviction.

Treason differs from other crimes in that there are no accessories. All are principals, including those whose acts would, in the case of felonies, make them accessories. Those who take part in the conspiracy which culminates in treason are principals, even though absent when the overt act is committed.

This doctrine, that all are principals, is not inconsistent with that other doctrine of American law which excludes “constructive treason”. To admit “constructive treason” is to hold a man as traitor when no levying of war has actually taken place. If such a levying of war has occurred, however, then those who were distant from the scene, but who gave aid, are principals in the perpetration of the crime.

Convictions for treason against the United States have been very few, and it is a striking fact that at no time in our national history has anyone actually been punished as a result of judicial conviction for the crime. Some of the leaders of the Whisky Rebellion of 1794 were convicted and sentenced to death as traitors, but were pardoned by President Washington.

In 1798 an insurrection in eastern Pennsylvania to resist a land tax passed by Congress gave rise to the famous Fries case. Fries was tried for treason, and it was in his elaborate charge to the jury, since often cited, that Judge Iredell declared that opposing the execution of any law by force of arms amounted to levying war. Fries was convicted and sentenced to death, but was pardoned by President Adams.

The Burr case was the most notable treason trial in our history, and it illustrated well the many legal obstacles that stand in the way of a conviction for this crime. In spite of the intense popular resentment against Burr, and the efforts of the Administration at Washington under President Jefferson to have him convicted, the jury found it impossible under the instructions of the judge, John Marshall, to bring in an adverse verdict, even though it seems clear that they desired to do so. Burr was known to be connected with an assemblage of men on Blennerhassett’s Island in the Ohio River, but as it was not proved that any act of war took place in connection with this assemblage, the evidence tending to show Burr’s connection with it was ruled out, and the prosecution had no other evidence to offer.

During the Civil War, the general law of treason was used but slightly, special acts being passed which related to the existing “rebellion”. The Treason Law of July 17, 1862 (called also the second Confiscation Act), is chiefly notable, perhaps, for its softening of the penalty for treason. According to the law of 1790, death was the only penalty, but few favored enforcing the extreme penalty against the thousands who were (according to the Union view) guilty of treason. The new act therefore gave the court the discretion to decree either death or fine and imprisonment for treason, while for insurrection or rebellion (which seemed to be recognized as a distinct offense in the law) death was not provided at all, the prescribed penalties being imprisonment, fine and confiscation.

Of the hundreds of thousands who were technically “traitors” during the Civil War, only a few hundred were even indicted. Of these only a very limited number were brought to trial, and none were actually punished for the offense. Cases of disloyalty amounting to treason were very numerous in the North, but the Administration at Washington preferred not to prosecute them. Lincoln’s well-known leniency was a factor of importance, and besides it was realized that conviction in regions likely to produce sympathetic juries would be difficult. To fail to convict would weaken the Government, while success might be even worse, for it would render the victim a martyr. Where zealous grand juries insisted on bringing indictments in spite of the district attorney’s wish to avoid prosecutions, considerable embarrassment resulted, and some of the judges showed irritation where cases of this sort were actually brought to trial. After the war indictments were frequently brought, but they were all dropped before conviction, only a few of them coming to trial. General Grant’s terms of surrender guaranteed that Lee’s men would be released on parole, and would not be molested by United States authority for participation in the rebellion. While it was not within the military power to grant such terms, they were respected, and these men were deemed beyond the reach of prosecution for treason.

In the case of Jefferson Davis, preparations were made for his prosecution, the charge being treason before the Federal Circuit Court at Richmond under the act of 1790, the penalty of which was death; but the general amnesty proclamation of December, 1868, caused the dismissal of his and all similar cases.

During the Great War, the Treason Law was found unavailable as a means of punishing disloyal and hostile acts, and the Espionage Act was passed to deal with the emergency. Four prosecutions for treason were instituted merely as test cases to develop the possibilities of the statutes, but none of them resulted in conviction. In one of these cases (United States vs. Werner in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 247 Federal Reporter, 708) the Government’s attorneys attempted to fasten the crime of treason upon the editors of a German language newspaper on the ground of discouraging enlistments, obstructing war measures, falsifying war news, and the like, but the court held that, while words published in a newspaper may be adduced to show treasonable intent if taken in connection with an overt act, and while the conveying of messages valuable to the enemy is treasonable, yet something more than the mere publication of sentiments must be shown.

This recapitulation will make it clear that the severity and extreme features of the Federal treason statutes make them really unavailable as actual instruments of judicial prosecution, and that in the rare cases when conviction has occurred, Executive clemency has always interposed to prevent punishment.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

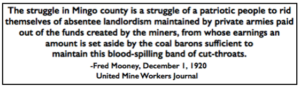

Quote Fred Mooney, Mingo Co Gunthugs, UMWJ p15, Dec 1, 1920

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=2hg5AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA23-PA14

The North American Review

(Concord, New Hampshire)

-Sept 1922

“The Miners and the Law of Treason” by James G. Randall

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.20482835&view=2up&seq=322

https://archive.org/details/jstor-25112811/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater

https://books.google.com/books?id=T00AAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=randall&f=false

IMAGE

Battle of Blair Mt, WV Today by Bushnell, Guards, Gunthugs, Spies,

-UMWJ p5, Sept 15, 1921

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=oHItAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.RA17-PA5

See also:

Tag: Battle of Blair Mountain 1921

https://weneverforget.org/tag/battle-of-blair-mountain-1921/

Tag: West Virginia Miners March Trials 1921-1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/west-virginia-miners-march-trials-1921-1922/

Tag: Billy Blizzard Treason Trial 1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/billy-blizzard-treason-trial-1922/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Battle of Blair Mountain – Louise Mosrie