—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday September 15, 1921

“Marching Through West Virginia” by Heber Blankenhorn

From The Nation of September 14, 1921:

Marching Through West Virginia

By HEBER BLANKENHORN

I

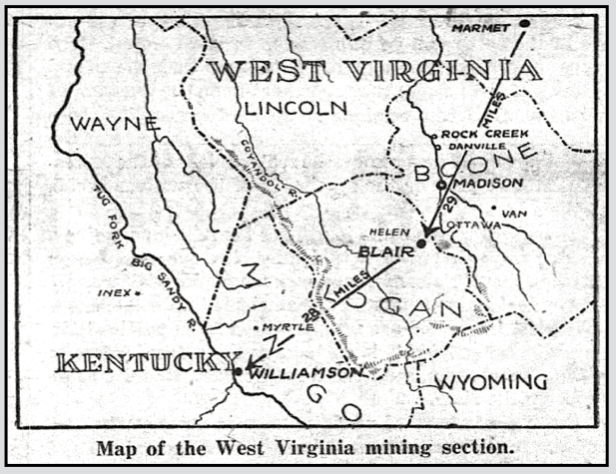

IF—as the war correspondents used to begin—you will place your left hand on the map of West Virginia, with the edge of the palm along the Kanawha River at Charleston, the down-pointing thumb will lie along the road southwest into Logan and Mingo counties, and the outstretched fingers will represent the valleys whence the miners collected for the march along the thumb-line. That region has filled the country’s newspapers with communiques, dealing with contending “armies,” “lines” held along Spruce Fork Ridge, intrenchments, machine-gun nests, bombing planes, so many dead for the day, so many wounded.

Marmet is ten miles from the State capital at the mouth of Lens Creek Valley. On the afternoon of August 22 a cordon of 100 armed men is stretched across the dirt road, the mine railroad, and the creek, barring out officers of the law, reporters, all inquirers. Inside lies the “trouble.” The miners have been mobilizing for four days. A snooping airplane has just been driven off with hundreds of shots. Accident and a chance acquaintance let me in.

The men, a glance shows, are mountaineers, in blue overalls or parts of khaki uniform, carrying rifles as casually as picks or sticks. They are typical. The whole village seems to be out, except the children, women, and old men. They show the usual mining-town mixture of cordiality and suspicion to strangers. But the mining-camp air of loneliness and lethargy is gone. Lens Creek Valley is electric and bustling. They mention the towns they come from, dozens of names, in the New River region, in Fayette County, in counties far to the north. All are union men, some railroaders. After a mile we reach camp. Hundreds are moving out of it—toward Logan. Over half are youths, a quarter are Negroes, another quarter seem to be heads of families, sober looking, sober speaking. Camp is being broken to a point four miles further on. Trucks of provisions, meat, groceries, canned goods move up past us.

“This time we’re sure going through to Mingo,” the boys say.

Them Baldwin-Feltses [company detectives] has got to go. They gotta stop shooting miners down there. Keeney turned us back the last time, him and that last Governor. Maybe Keeney was right that time. This new Governor got elected on a promise to take these Baldwin-Feltses out. If nobody else can budge them thugs, we’re the boys that can. This time we go through with it.

“What started you?”

This thing’s been brewing a long while. Then two of our people gets shot down on the courthouse steps—you heard of Sid Hatfield and Ed Chambers? The Governor gives them a safe conduct; they leave their guns behind and get killed in front of their wives. It was a trap.

“But that was several weeks ago.”

Well, it takes a while for word to get ’round. Then they let his murderer, that Baldwin-Felts, Lively, out on bond-free-with a hundred miners in jail in Mingo on no charges at all—just martial law. Well, we heard from up the river that everybody was coming here. We knew what for. When we found lots had no guns we sent back to get them.

Bang! Bang-bang! from below in the valley. “That’s a high-power,” one remarks.

What are those damn fools wasting ammunition for? Maybe that airplane’s come back. You know, several hundred service men was drilling this morning. After five minutes they was putting right smart amount of snap into it.

We have forded the creek a dozen times, have passed through Hernshaw—a mean-looking mining village—we pass hundreds of men; then an auto with women passes us.

[U. M. W. Nurses]

“See our Red Cross nurses?”

The women have nurses’ white head-dresses, with big blue letters on the band over the brow, “U. M. W.”

They’re wives of some of the boys. They’ve had experience nursing. They say they’ll see this through.

A man says:

I got five children. I worked once in Logan. I thought this thing over a long time ‘fore I started. Now I ain’t going back.

He thoughtfully weighs some long brass cartridges in his hand. Four others in the group do the same. The five kinds of heavy cartridges are all different, but each gun looks spotlessly well kept.

One youngster in uniform even wears his overseas cap. “Does this look like the Argonne?” “Them hills wasn’t so steep.”

At the upper camp are a thousand men in a group. Expressions of determination are frequent and profane. Explanations of the “army’s” purpose do not agree. “We want the law.” “We want justice.” “We’re going to drive out the mine guards.” “Going to get our people out of jail.” “A protest against the Governor’s martial law in Mingo.”

A pleasant man remarkable for a white collar is easing a pistol out of his belt. “What do you boys really think you can do?” He gives a short laugh.

Well, John Brown started something once at Harper’s Ferry,

didn’t he?Back in Charleston I was still wondering what to reply. But the “army” seemed too many-headed ever to march.

II

So much for the “inside.” Outside the Charleston newspapers displayed some perturbation over the miners at Marmet, who were “ravishing the country, robbing passers-by, and threatening death to law officers.” A “law and order league” to counteract the “crime wave” had just been organized. Governor E. F. Morgan had addressed it; “moonshine liquor, pistol-toting, and automobiles” were the three great evils responsible for West Virginia lawlessness, he said; the miners were at Marmet “for the sole purpose of terrorizing the government of the State.”

Otherwise West Virginia was normal; the strike of miners in Mingo County was still on, in its fifteenth month. The heads of the union, C. F. Keeney, president, and Fred Mooney, secretary, of District 17, United Mine Workers, “had washed their hands” of the Marmet affair.

Next day “Mother” Jones, veteran organizer of the U. M. W., exhorted the miners to disband. She read what purported to be a telegram from President Harding promising that the Baldwin-Felts mine guards would go. The miners, through Keeney and Mooney, learned from the White House that no such telegram had been sent. That night the army, now swelled to 8,000, marched.

Coal mining in central West Virginia stopped. Miners with rifles, by the thousand, poured into Marmet, some riding on the tops of passenger trains. War maps with red and yellow pins appeared in Charleston shop windows, showing Spruce Fork Ridge on the border of Logan County as the “line” held by Sheriff Don Chafin with his deputies and mine guards, machine-guns, and two bombing planes. The Governor called for Federal troops. By Thursday night the “army” was strung out half across Boone County. They were marching in companies, in something like military order. At times they stopped to listen to speeches in which “deserters were cussed out”; or to listen to leaders on how to fight machine-guns—”lie down, watch where the bullets cut the trees, outflank ’em, and get the snipers.” Stores in Peytona, Racine, and Madison were selling or loaning them all available stocks of food and guns. Women along the way set out food. Several doctors joined the army. Men who fell out had to leave their guns and cartridges behind.

At three o’clock Friday morning Brigadier General Bandholtz from Washington routed the Governor out of bed. At four he sent for Keeney and Mooney. He said curtly that the situation was in his hands and that he had “no concern with the merits of the controversy.”

“What’s the object of these miners?”

“To get the Baldwin-Felts detectives out.”

“Do you think they will accomplish their object?”

“No.”

“Can you stop them?”

“Probably.”

“Will you try?”

At five o’clock Keeney and Mooney were pursuing the “army.” By evening they were turning back the head of the column and ordering special trains, passenger and electric, to haul all home. But some of the men were so dissatisfied that they commandeered a train that night, loaded it up with men and sped, headlight out, down the valley to Logan County. There they joined the union miners around Sharples, Blair, and Clothier, and found fighting.

General Bandholtz returned to Washington, first sending for Keeney and Mooney. He complimented them for their “efficient action.” Then he read a statement for the press, holding them “responsible for the acts of the members of the society which they represent.” Keeney hotly resented this. The general urged Keeney to use his influence to disarm the miners: “I’ve seen enough of shootings and hangings following insurrections. We don’t want any more.”

[Retorted Keeney:]

Shooting and hanging don’t scare me. Taking guns away from the miners is hardly my business. We have a constitutional right to bear arms—about the only right left to us. I’ve a high-power rifle, three pistols, and a thousand rounds of ammunition at home. I’d like to see anybody take away that gun—except smoking.

General William Mitchell also departed. He had flown in, wearing a pistol, four rows of ribbons, and two spurs (he is chief of the air service). “All this could be left to the air service,” he said. “If I get orders I can move in the necessary forces in three hours.”

“How would you handle masses of men under cover in gullies?”

“Gas,” said the general. “Gas. You understand we wouldn’t try to kill these people at first. We’d drop tear gas all over the place. If they refused to disperse then we’d open up, with artillery preparation and everything.”

“What are you going to do about the other ‘army’ of deputies, etc., in Logan County?“

But those “were peaceful citizens defending their homes“; as for the machine-guns and bombing planes, “they belong to the sheriff, don’t they?”

III

Such are the facts. They do not inspire confidence in the workings of government and law which the miners at Marmet so seriously affronted. For sanity, the actions of government and of the miners’ army seem to be on a par.

The “trouble” in West Virginia is several years old. Its peculiarities are West Virginian but its bases are industrial and national. It has been marked by killings on both sides, by “investigations,” by evils condemned, and nothing done.

It might be more sensible in dealing with West Virginia to begin by facing three facts. First, the present phase of civil war has lasted since 1919, its main features unchanged, with no attempt to change them hitherto by the Federal Government. An outbreak was bound to come. Second, the outbreak was a rising of a considerable section of the people, not a mob of toughs. Estimates of the “army” ran from 10,000 to 14,000. Perhaps two or three times that number of people actively abetted or openly approved the march. Third, these people took the law into their own hands because they believe that that is precisely what “the other side” has been doing for a long time.

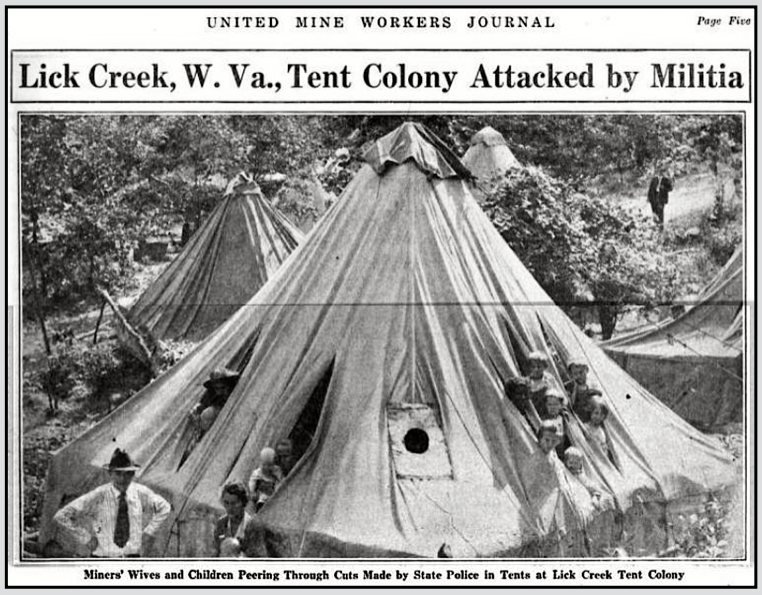

They believe that the coal operators have long supported private armies, chiefly Baldwin-Felts “detectives,” who beat up or kill union miners; that lawless mine guards are frequently cloaked in county or State authority. They will tell you that on June 14, Flag Day, members of the State constabulary, aided by sheriff’s deputies, assailed the Lick Creek tent colony. This camp contains part of the 10,179 men, women, and children of the Mingo strike who are still drawing relief from the union. The constabulary shot dead Alex Breedlove, a striker, then slashed many tents to pieces and destroyed the strikers’ food supplies.

It is public record that the recruits for the State constabulary were picked from lists provided by the coal operators. The law provides that the members must be residents of West Virginia and file a bond. No such bonds have been approved by the State Treasurer. On July 8 the State constabulary shut up the union offices at Williamson, arrested twelve union officers and strikers there, and put them in jail under the martial law which Governor Morgan had declared in Mingo County. It is public record that this martial law was being enforced only against miners’ assemblies, commercial and other associations being allowed to meet freely. Some of these officials have been fighting the union since 1912.

On August 1 came the killing of Sid Hatfield and Ed Chambers, on the steps of the courthouse in McDowell County, by Baldwin-Felts gunmen. The gunmen’s leader, C. E. Lively, had been a spy inside the union for years, then served a year in prison in Colorado for killing a striker, then testified before the Senate committee in Washington last month; after being arrested for killing Hatfield he was released under bond. Hatfield and Chambers were members of the union; two other members, Collins and Kirkpatrick, who escaped the gunmen by running, were, with Mrs. Hatfield and Mrs. Chambers, to have told their stories at a mass meeting in Charleston on August 27. The authorities suppressed the meeting.

Thus 10,000 mountaineer miners have come to believe that certain persons have been taking the law pretty completely into their own hands. They retaliate in kind. It is hard to interest them in senatorial investigations. They may come to believe that the Federal as well as the State Government cloaks operators who take the law into their hands. Then they will talk even more of John Brown and Harper’s Ferry.

—————

[Photographs, paragraph breaks and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote Fred Mooney, Mingo Co Gunthugs, UMWJ p15, Dec 1, 1920

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=2hg5AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA23-PA14

The Nation Volume 113

(New York, New York)

July-Dec 1921

https://books.google.com/books?id=4Pw4AQAAMAAJ

-Sept 14, 1921

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=4Pw4AQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA278-IA3

-page 288: “Marching Through West Virginia” by Heber Blankenhorn

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=4Pw4AQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA288

IMAGES

Miners March Map Marmet to Mingo, NY Dly Ns p8, Aug 27, 1921

https://www.newspapers.com/image/410259989/

Mingo Co WV, Lick Creek Tents Destroyed, UMWJ p5, Aug 1, 1921

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=oHItAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.RA14-PA5

See also:

Heber Blankenhorn (1884-1956)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heber_Blankenhorn

From Justice (ILGWU) of Sept 23 & 30, 1921

-repubed article in two parts, scroll down:

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/83158/Justice_3_39.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/83159/Justice_3_40.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Gun Thugs, Rednecks, and Radicals

A Documentary History of the West Virginia Mine Wars

-ed by David Alan Corbin

PM Press, 2011

Note: see page 140

https://books.google.com/books?id=zHH7BgAAQBAJ

Tag: West Virginia Miners March of 1921

https://weneverforget.org/tag/west-virginia-miners-march-of-1921/

Tag: Mingo County Coal Miners Strike of 1920-1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mingo-county-coal-miners-strike-of-1920-1922/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“We’ll hang Don Chafin to a sour apple tree,

Hang Don Chafin to a sour apple tree,

Hang Don Chafin to a sour apple tree,

As we go marching on.”

-to tune of John Browns Body

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?extid=SEO—-&v=351054712711964

John Brown’s Body – Paul Robeson