———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday January 4, 1920

Mary Heaton Vorse Reports from Front Lines of Great Steel Strike

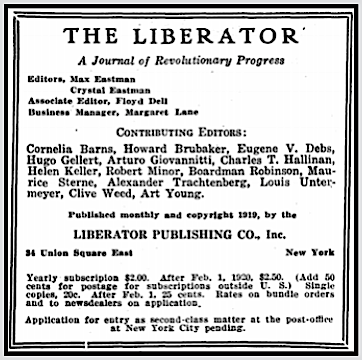

From The Liberator of January 1920:

The Steel Strike

By Mary Heaton Vorse

—–

AT the beginning of the fourth month of the strike, at a moment when the newspapers have definitely decided that there is no strike, the strike still cripples production of steel 50 per cent. These are figures given by the steel companies to the financial columns of the daily press. One would think that the strike would have been definitely battered down and the account closed for good in at least a few towns.

One would think that the might of the steel companies, backed by the press, reinforced by the judiciary, local authorities and police, and self-appointed “citizens’ committees,” would have finished this obstinate strike. One would think it would have been kicked out, smothered out, stifled out, bullied out, brow-beaten out, stabbed out, scabbed out, but here they are hanging on in the face of cold weather, in the face of abuse and intimidation, in the face of arrests, in the face of mob violence-and these are dark days too.

These are days when the little striking communities are steeped in doubt, when the bosses go around to the women and plead with them almost tearfully to get their husbands to go back to work before their jobs are lost. These are the days when in these isolated places every power that the companies know is brought to bear upon the strikers to make them believe that they and they alone are hanging on, that the strike is over everywhere else and that this special town will be the goat.

People talk of the steel strike as if it were one single thing. In point of fact, there are 50 steel strikes. Literally there are 50 towns and communities where there to-day exists a strike. The communication between these towns is the slenderest, the mills and factories which this strike affects line the banks of a dozen rivers. The strike is scattered through a half a dozen states.

This is something new in the history of strikes-50 towns acting together. Pueblo acting in concert with Gary; Birmingham, Alabama, keeping step with Rankin and Braddock, Pennsylvania. How did it happen that these people; so slenderly organized, separated by distance, separated by language, should have acted together and have continued to act together?

Some of the men have scarcely ever heard a speaker in their own language. Some of the men are striking in communities where no meetings are allowed. Sitting at home, staying out, starving, suffering persecution, suffering the torture of doubt, suffering the pain of isolation, without strike discipline and without strike benefits, they hold on. What keeps them together?

It seems as though a great spiritual wave had lifted up the heaving mass of the people and sent them irresistibly forward, hurled them against the reactionary might of embattled steel. As though their will to freedom from industrial tyranny had resulted in some conflagration of the spirit which made nothing of space.

—–

The strike has gone through three phases. The first was terror. Men were beaten and arrested. Houses were searched. In Allegheny County the State Constabulary rode down the strikers. They rode their horses into stores and houses. They rode their horses up church steps and into crowds of school children. The idea was to stamp out the strike.

It refused to be stamped out.

The next phase was intimidation, silence, persistent reports that the strike was over. If they couldn’t stamp it out they might smother it.

But the strike couldn’t be smothered.

The situation of the consumers of steel became desperate. Everything from wire and ball-bearings and nails, to engines and parts of buildings necessary for structural iron work, was lacking. If the strike was over, the consumers wanted to know why there was no steel. Something had to be done.

Violence began again. This time mob violence added to judicial and police violence. Leaders were arrested. Secretaries were run out of town. Citizens’ committees were formed. Negro strike breakers, and more negro strike breakers, were brought in. Mills were pried open by fair means or foul, and a constant drive of intimidation was brought upon all organizers and secretaries. We are in that phase now. When an organizer is missing for two or three hours foul play is feared, and every day brings the news of arrests. Every day a new community takes its turn in the limelight.

It is now Donora’s turn. A few days ago, F—–, the local organizer of Charleroi, telephoned that 101 men had been arrested.

A house in Donora had been blown up. This was the chance for which the authorities had been looking. They threw a cordon of police around the Lithuanian hall, the strike headquarters, and arrested every one there indiscriminately, including the secretary. You may be sure that he was not omitted. He is an active man, the secretary of Donora, and they have been after him a long time. They have told him they “would get him.” They would have gotten him long ago if they dared.

The first time I saw Donora was on Thanksgiving Day. The car that takes you there is called the “scenic railway.” It goes through a country as romantic as the Berkshire Hills. There are abrupt hills and swift streams, dense woods. This sweet country has here and there a blot of a little black sordid town. Towns made of shacks, towns, without self-respect, towns that offer the worker nothing but his existence.

Steel and coal have reigned here. They have reigned here undisputed since the beginning. They have given their workers a scant livelihood without the decencies of existence.

—–

Their long reign has made towns like Donora. It is a long thin meagre town. Mills rampart it. It is desolate, abandoned-an aggregation of mean streets and meaner houses. Groups of men were standing about the corners idle. I asked the first man I met where the strike headquarters was, and he directed me to the Lithuanian Hall, which contains both strike headquarters and the commissary. The never, failing group of men stood around the bulletin board reading the latest strike news.

“Where’s H—–?” I asked.

“Two plain clothes men came and got him-we’re afraid they are going to arrest him just to spoil our dinner.” One of the men, H—–‘s assistant, took me down the stairs.

“I tel1 you I had a pretty hard time to keep the boys quiet after they took H—- away!” he told me.

The smell of turkey was in the air; long tables were set out. The men were eating their dinner or lining up for it-the dinner was 5 cents a plate-to those who could afford it. Men who had savings had contributed to this fund, so that the single men without savings could have turkey. The place was full of good fellowship. But there was something else in the air-an uneasiness-as if everybody was waiting for something to happen-a lurking sense of disaster.

It had persisted even after H—– came, unharmed this time, merely warned there could be no speeches after dinner. This atmosphere of uneasiness exists in all the towns. For not only are the police suspicious and hostile, but the threat of white terror lurks continually. “Citizens’ committees” are formed, and there is no telling when the mob spirit will unloose itself, and the strikers and the organizers know it.

I went up to the office of the constabulary and there I met the burgess.

“Our people were all right,” he said, “before these agitators got in here,” and he shot a poisonous glance at H—– as he talked with the chief of police. That, in the minds of the authorities and the officials, accounts for everything. Outside agitators made the trouble. The people were all right until they came. The 350,000 men who walked out of the mills were happy and satisfied and they walked out just to make a living for these agitators. That is what the organizers came for. They are professional trouble-makers and would have to do an honest day’s work if they were not stirring up the contented people.

Such is the simple reasoning that you will meet in the steel towns on every hand. The obvious conclusion is, “Lynch the organizers-if you cannot lynch them, deport them, arrest them-and the ignorant foreigners will be good again.”

So things were stewing and boiling, getting ready for the recent arrests. The superintendent of the mills spoke from his automobile urging the workers to go back; no one stopped him-naturally. Had a strike sympathizer spoken publicly it would have been called inciting to riot, nothing less.

When Z—– was shot in the leg by a colored scab while he was on picket duty he was arrested. He was in jail from Thursday to Monday, nor was his wound dressed. His money was not returned to him. The doctor who afterward dressed his wound charged him $5 and turning to H—–, who accompanied him, said accusingly:

“Young man, you are following strange gods.”

“They shouldn’t be strange to you,” H—– answered, “they’re the gods of Thomas Jefferson.”

—–

Well, this dangerous H—–, who started soup kitchens for single men and followed the gods of Thomas Jefferson, has finally been arrested on a charge of intimidation and conspiracy, he and a hundred others. While they were in jail the bosses came to them and offered to withdraw all charges if they would return to work. They all refused, and 75 refused bail. So they were loaded into open trucks to cart them over to the county seat, a four hours’ journey. This by way of breaking their morale. But, before they left, their wives and their friends crowded around them and cheered and they went off cheering.·

This is the history of one town, the latest to add to the collection, for violence and the menace of violence is always around us.

We cannot forget Fannie Sellens [Sellins]. They “got her,” as the saying is. She was bending over some children. The gunmen shot her in the back. There was n0 one arrested. They shot her in the back-they shot her again in the temple after she died.

The other, day some men from Hammond came in. They had with them photographs of four dead strikers lying stiff and rigid in their Sunday clothes, flowers about them, flags behind them. They had been shot in the back also after the gunmen had called “Hands Up!”

Foster’s strangely quiet office is the clearing house for all these happenings; the victims come here in an unending trickle. Now the ‘phone buzzes the news of a fresh arrest. Now it is M—– from Clairton, with two Slovak boys. M—— is a black flame flickering with the wind of anger. He is one of those thin dark men who make you think of a drawn blade. An indefatigable worker, M—– has given to his union the intense and passionate allegiance that some men give to their country. By his own efforts he has brought in 1,200 men. They have arrested him, fined him, threatened him, and each and every threat and each and every arrest is like oil thrown on a blazing fire. He is a Croatian, and his lean dark face looks as though he had Gypsy blood. He was quiet in the excitement of his anger.

“Show your wrists,” he said. The two boys stolidly exhibited their wrists. They were swollen and bruised. “You should see them when they got loose four or five hours ago,” he said with dramatic gentleness. He waited for our question of what had happened.

“Handcuffed all day to beds in hotel room,” he threw at us laconically-the, boys nodded. They had round blond heads, fine looking boys, sturdy and clean. M—– went on in quiet intensity with his story, the boys from time to time throwing in unemotionally a detail like, “Then the Cozack hit me and called me ‘you damn Bolshevist.'”

Simmered down, their story is this: Led by a scab, members of the constabulary entered the house of these boys and conducted a search for the scab’s trunk-he said that some one had stolen it. I quote from their affidavit:

The members of the state constabulary went to the room of the two complainants and slapped Ferkas and punched Tasich and took both of them to a room on the third floor of the Clairton Inn where the Constabulary makes its headquarters.

About six or seven members of the state constabulary began to torture the two strikers.

The men were taken to different rooms. Ferkas was placed on a chair, arms were twisted and handcuffs were slipped on and fastened to the iron rail of the bed, so that he was forced to bend over. He remained in this position from 9 A. M. to 4:30 P. M., weeping and crying from pain of the handcuffs, which were fastened so tightly that the wrists became swollen. A drink of water was refused and appeals to loosen the handcuffs resulted in state troopers coming in at different times and making them tighter. When he was released Ferkas could hardly see.

Tasich was fastened standing up to the end of a high-iron bed, the handcuffs were fastened so tightly that the pain was intense and after four hours the handcuffs were hidden in the swollen flesh. Cries of pain resulted in Tasich loosening the left handcuff, but tightening the right one. He was hardly able to walk when he was released. He was beaten while handcuffed by three members of the state constabulary. A piece of cloth was given Tasich so that the blood flowing from his nose after the beating would not drop on the floor. Blood did get on the carpet. Between beatings, Tasich was asked of the whereabouts of the trunk, of which he knew nothing. Finally he was released and his hands were so badly swollen that the next Sunday at noon marks of handcuffs could still be seen at the wrists.

Three $50 Liberty bonds and a bank book showing deposits of $1,150 in the Union Trust Company of Clairton, were taken from Ferkas. Tasich lost $11.00 in cash and his bank book showing deposits of $1,380 on the Monongahela Trust Company of Homestead.

I have given this in full because I would like some light on the psychology of this constabulary with its arrogant contempt for human life and liberty, its scorn for justice and law.

—–

Stories like these have poured over us in a deadening stream-we have stopped realizing their full significance, so accustomed have we become; but that is not the worst. It is serious, but it is a condition made possible by another terrible circumstance, and that is the silence which surrounds us. To all the waiting public of America nothing of our struggle or our reasons for it has penetrated. We shout out to the sympathy of the world, but it is as though we are in a vacuum. No one hears us. No one knows what has happened to us. No one knows what we are fighting for. We have the sense of living in a world of deaf people.

What strange hate to visit upon the simple men who have made the wealth of the country, and whose youth and strength withers before the fierce blast of the furnaces, and whose crime it has been to ask only the conditions which the Government gives its employees, the conditions which England’s workers in steel have long since had.

Out in the world they are banging away about Americanization. Yet the fight for Americanization is going on here. It is the strikers who are waging it. Out in the world they are diverting public attention by wagging at the public a red bogey which has Foster’s face.

We know that women have met together in this town, kind women no doubt, no doubt good women-women from comfortable homes, women dressed in furs-and railed at the strikers. It is fashionable to call this strike by the dread word “unAmerican.” Why do they hate these toiling people? Is it hate, perhaps, for people they have deeply wronged? With the hate is there perhaps mingled a subconscious memory of who it was who first said, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

In these pictures you have the elements of what keeps the strike alive. It is strongest where oppression is strongest. It is strongest where persecutions have been most constant.

Such stories are not the only ones you get in Foster’s office. The amazing details of devotion that pour in daily would break your heart. Households on the edge of want, waiting a week and another week before going to the commissary. In one town the ration is for 300 families, yet 500 are served. Do you know how this is done? These needy people give back food-supplies voluntarily, taking what only will barely suffice them.

Weekly they are drawing from their store the money that has meant self-denial of the strictest sort. It was to them their insurance for old age. It was insurance against those bleak hours, when unemployment thrusts its gaunt face of starvation in the door. For they are investing their money in freedom. Freedom from the terrible twelve-hour day. Freedom to join the organizations they choose, unmolested. It is this will to freedom which inspires the inarticulate anonymous people who form the background of this strike.

When they came through the gateway which leads to America, the eyes of the men and women now striking in the steel industry rested with faith upon the figure of a woman who held a lighted torch to heaven.

This figure was not merely a monument. It was a promise. This lighted torch was the symbol of a deep reality. Through many years they have held the memory of it enclosed within their hearts. The steel companies betrayed that promise. Now they are demanding that it should be kept. This was why the strike swept through the country like a flame. It leaped from town to town and from one state to another. A common impulse swept these people forward. A common impulse toward freedom gave them steadfastness and gave them their desperate and enduring patience.

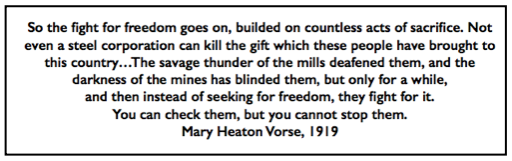

The stuff of their resistance is made of a hundred thousand sacrifices and kindnesses. They have opposed the might of the steel corporations with hundreds of acts of unconscious heroism.

To know this one must go around among them in their homes.

—–

There is no investigator for the commissary who will fail to testify to this. Instead of strike benefits, rations are given twice a week to those who need it. There are two sets of rations; one for a family of five and one for a family of over five. Before the commissary card is given out an investigator goes to see the striker. In Braddock I went around on a tour with a Polish investigator. “What do you say to them?” I asked him.

“Me? Oh, I say like this: ‘Ma’am, could you maybe wait one week or perhaps two week? Ma’am, think how it is that you want this strike to win; and if there is somebody maybe needs helping more than you.'”

A rather hard proposition to put up to people who have already applied for aid-a hopeless mission, one would suppose. We went down Braddock’s mean streets. The decencies of life ebb away as one approaches the citadel of the Edgar Thompson Plants. We passed along an alley in front of which there was a field where the filth and refuse of ages had been churned into a viscous mud. A lean dog was digging in the slime. Refuse and ancient rubbish littered the place. Some pale children were paddling in the squashy mud. Beyond was the railway track; beyond that the mills: Two-storied brick houses flanked the brick street. The courtyard back of the houses was bricked; there was no green thing any where. But in the back courtyard some Croatian women were weaving rag rugs. In their own homes they had woven the winter clothes of their men; and here in the squalid Braddock alley they wove bright colored rugs and sang as they wove. Here and there men had brought tables out of doors and were playing cards. They nodded to us in a kindly village fashion as we passed by.

We went into a house in which there was a superficial untidiness. The work that this woman had to do was getting hard for her. There were two babies already, and very presently there was going to be another one. She came forward smiling, greeted me in little broken English and began talking eagerly to my guide. He turned to me.

“She say, it all right. She say how she don’t need commissary after all. She say let somebody else take her place right off. She get a lady to give her some washing to do. Pretty soon she ain’t able to wash no more. Then she take commissary, she say.”

He told me this in a matter of fact tone. These stories are commonplace among these people working to win the strike; this woman whose tell-tale house showed how hard the work already was getting for her, who acted as though a legacy had been left her when she got a “lady’s washing to do” is no exception, no isolated case. On all sides they are fighting oppression with the weapons of courage and endurance.

I went out from this house into the sordidness of the Braddock streets. A woman was sitting quietly beside her door, a child in her arms, another playing at her feet. Her mild eyes gazed placidly in front of her as though they did not see the monotony of the dreadful street, punctuated with its obscene litter. The street ended with the red cylinders of the mills, vast structures rearing their monstrous tank-like bulk far into the air. Above this landscape at once squalid and monotonous rolled the sombre magnificence of the smoke. It seemed to me that this woman had the patience of eternity in her broad quiet face.

She seemed to symbolize the people of the strike. There is about them neither threat nor menace, but a patient sort of certainty that comes with the sure knowledge that their battle is a just one and is being fought with the weapons of justice.

———-

—–

[Emphasis added, photographs added, drawing by Lydia Gibson with original article.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote MHV Immigrants Fight for Freedom, Quarry Jr p2, Nov 1, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/405049859

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-Jan 1920, page 16

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/01/v3n01-w22-jan-1920-liberator.pdf

IMAGES

From “Closed Towns” by S. Adele Shaw-Survey of Nov 8, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA58

See also:

Tag: Mary Heaton Vorse

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mary-heaton-vorse/

Tag: Great Steel Strike of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/great-steel-strike-of-1919/

Tag: Fannie Sellins

https://weneverforget.org/tag/fannie-sellins/

Tag: Hammond Massacre of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/hammond-massacre-of-1919/

Men and Steel

-by Mary Heaton Vorse

Boni and Liverright, NY, 1920

https://archive.org/details/mensteel00vors/page/n5

Labour Pub Co., London, 1922

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000017075145&view=2up&seq=8

Re Organizer Mestovic and 2 Slovakian boys, see:

https://archive.org/details/mensteel00vors/page/70

Lydia Gibson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia_Gibson

http://www.laborarts.org/exhibits/themasses/bios.cfm?bio=lydia-gibson-minor

Re Mary Heaton Vorse, Gibson, & Robert Minor, see:

https://spartacus-educational.com/USAvorse.htm

In 1920 Mary Heaton Vorse began living with Robert Minor, a talented cartoonist and founding member of the American Communist Party. She suffered a miscarriage in 1922 and soon afterwards Minor left her for illustrator Lydia Gibson. The couple got married in 1923. As a result of the trauma of these two events, Mary became addicted to alcohol. However, she broke the habit in 1926 and she returned to writing.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fannie Sellins – Anne Feeney

Lyrics by Anne Feeney