———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Saturday July 31, 1920

“The Mexican Revolution” by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman, Part III

From The Liberator of July 1920:

The Mexican Revolution

By Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman

[Part III of III.]

There are other interesting personalities behind the new revolution-Calles

[Plutarco Elías Calles] (pronounced Kah-yayz), for example, ex-military governor of Sonora, Secretary of Commerce and Labor and leader of the Sonora secession. He is without doubt the most forceful, the most radical, the most intelligent and widely informed among the present leaders of Mexico.As governor of Sonora he proved himself a champion of labor, and he gave the Indians lands, and each a gun and five hundred rounds of ammunition with which to protect and hold them. Carranza immediately telegraphed him, when these acts became known, to take back the lands. Calles replied: “Send a stronger man than I am, for I can’t do it.” Calles has tried to enforce Article I23 of the Constitution, which is the most enlightened labor code of any capitalist country. As a result the Phelps-Dodge Company, which operates the great copper mines at Cananea, closed their works. Calles instructed the workers to take charge of them and run them. He told me how surprised he was to see how well they did it. The representatives of the Phelps-Dodge Company hurried back upon the scene with a great bill for damages. Calles admitted their claims, but then he turned to the Mexican constitution.

“I read here,” he said, “that any company that ceases operations without giving two weeks’ notice must pay three months’ salary to its employees. Go bring your payrolls, and we will strike a balance to see how much YOU owe the workers, whom I represent.” The mine representatives decided to return to Cananea and put in safety appliances, build club rooms, reading rooms, and, to crown all, a huge concrete swimming pool for the workers.

“Do you know of any other mine in the world that has a swimming pool for its workers?” Calles asked me as he told this story, and then he laughed. At the same time the same company, just over the international line in Bisbee, was driving its workers, across the heat-eaten sands of the desert. so Calles, not being able to enforce Article I23 in the civilized United States, did what he could by sending food to the unfortunate victims.

Some mine owners down in Sinaloa had not heard of these things. They sent to Calles asking him if he could supply them with some good docile workers. He picked out the most intelligent union men he could find in all Sonora and sent them down to work. Within a week they had the Sinaloa workers organized and on strike to demand decent conditions.

Perhaps the most striking accomplishment while he was governor of Sonora was his ability to pacify the Yuaqui Indians, something that had not been done even in the days of strong-arm Diaz.

When Calles came to Mexico City to act as Secretary of Labor, I went to him, having heard of his work and his attitude, with a copy of Bullitt’s report on Russia, hoping to have him translate and publish it. He laughed when I mentioned it, and, turning to his books, said:

“Here it is. I just finished having it translated. Great stuff, isn’t it. I’m going to have it printed as one of the documents of the Labor Department.”

But it was never issued. (Portions appeared in a Yucatan paper.) Blocked at every turn in his efforts to enforce the Constitution, he finally resigned his post and went back to Sonora as a private citizen to organize the workers. Carranza, perhaps having learned from peacock Wilson the possibilities of governing without a government, called no cabinet meetings while Calles held the portfolio. Calles could not enforce the eight-hour law, the minimum wage, workers’ insurance-he could not even appoint a single factory inspector. By the most strenuous efforts, he prevented Carranza from sending machine guns during the great strike of textile workers in Orizaba. He boldly took the side of the workers and informed the factory owners that if they did not grant the strikers’ demands the government would take the factories over and run them. That ended Calles with Carranza.

One of the most picturesque figures in the new movement is Felipe Carrillo, ex-president of the Liga de Resistencia of Yucatan, who has been fighting out in the hills of Zacatecas since the revolution started.

Felipe began his career as a radical in the days of Diaz. As some people have thought to their sorrow in the United States, he believed that the Constitution of the nation might be distributed to the people to be read. Accordingly, he translated the Constitution of the land, the enlightened Constitution of the great old Indian, Benmerito Benito Juarez, into the Maya dialect, and began reading it on the great haciendas. He went promptly to jail. The Constitution was a sacred and holy document, not to be profaned by public sight and hearing, a document that was to be kept in the national archives and the Biblioteque Nacional, and only taken out on special occasions for the hoary and erudite sages of the Supreme Court to peruse slowly and solemnly and con dignidad that they might write lengthy, weighty and incomprehensible decisions for the proper guidance of the dear people.

In six months Filipe was out-and mad. He began making speeches to the peons on the haciendas. His brother-in-law, however, was a rich hacendado who believed that freedom consisted in his right to put chains on the legs of his peons. His brother-in-law loved radicals. His brother-in-law sent a man to kill Felipe. The man fired at Felipe in a public meeting, but missed. Felipe pulled his gun and shot the man dead. Felipe went to jail for manslaughter.

When Alvarado came to Yucatan, Felipe was released, and set to work ardently to organize the great Liga de Resistencia, which Carranza later destroyed with murder and rapine.

I remember listening to Felipe addressing the Indians one Sunday. He knew the old religious superstitions of the decades of the domination of the Spanish Church and State must be broken down before he could form any real radical organization. It was a subject that always required careful handling. I remember how cleverly he worked up the subject until he had the Indians with him. I remember how he cried out:

For the love of Jesus you used to get up at three o’clock in the morning to go to work; for the love of Jesus you were whipped to work; for the love of Jesus your women were raped by the hacendados; for the love of Jesus you were hungry and ragged; now for the love of the devil you have happy homes and bread and your own bit of land.

I remember how the plaza rocked with the shouts of: “Viva el Diablo, viva el Diablo!”

Perhaps that is why, among other things, the Mayas turned the churches of the Conquest into meeting places for the Ligas de Resistencia.

I met Felipe immediately he came to Mexico City just after he had been forced to flee for his life, when federal troops had flogged one hundred of his neighbors in the public plaza of his home town. Murder was tearing Yucatan in its teeth; rapine was stalking in blood across the Peninsula.

Felipe was heart-broken. His beloved Indians, had been shot down by hundreds on hundreds. The work of years had been destroyed in a few months. He felt himself back in the Diaz days.

“All is lost,” he would groan, “all is lost.” He had no spirit for anything. He scarcely cared to live.

I met him again when he came back from the hills of Zacatecas, brown and hard as nails. He was the same old Felipe again-joyous, over-optimistic, enthusiastic. He was burning to be off to Yucatan.

[He vows:]

This time, I will do as Calles did in Sonora-give the Indians lands and guns. All Mexico and all the world will not take our rights away from us a second time.

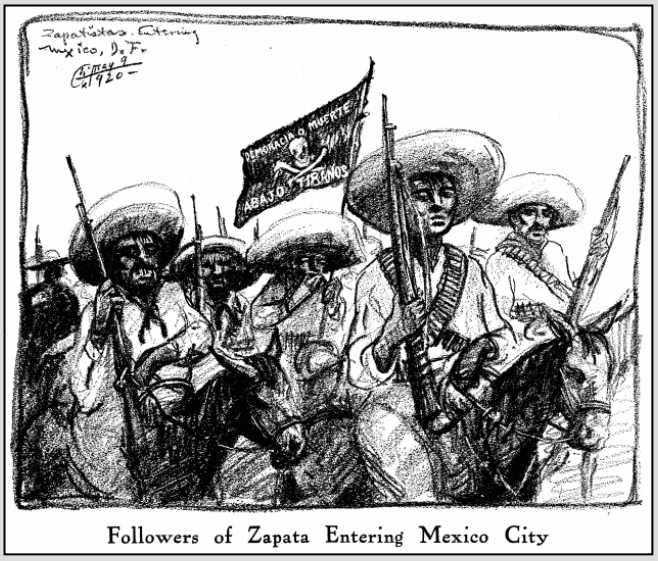

There is a sentiment among all the leaders behind the new revolt to give the people land-Obregon, Calles, Carrillo, de la Huerta, provisional president and ex-chief of cabinet; Villareal, the most uncompromising agrarian of the revolutionary period, and now to be named Ministro de Gobernacion, Soto y Gama and Magaña, for

ten years irreconcilable Zapatista leaders-all have made public statements in favor of allotting available lands to the people immediately. This work has already begun, in fact, a few days after the revolution.To-day, for the first time since Madero, the trains of Mexico are running on schedule without military escort. Every rebel, except the impossible Villa, has pledged support to the new movement-Palaz, the autocrat of the oil district, who is to be quietly side-tracked; Soto y Gama, the lawyer who has been fighting for ten years in the mountains of Morelos for land reform; Mixieuero, the peasant leader of Michoacan.

A cuartelazo is not a social revolution, and giving lands to the Indians is not Socialism, nor is it the ultimate solution of Mexico’s problem. But it is not too much to say that never before during the past ten years of Mexico’s checkered history has an event so fraught with social significance occurred as the recent “commotion,” which changed the personnel of the government. Progress for some time to come in Mexico must depend upon such changes of personnel-until some form of political and economic organization is built up among the people. The present leaders have promised to further that organization, to permit labor to organize, to teach the peasants to form co-operative associations. It has been proposed to establish a national minister of propaganda, who will carry the meaning of the revolution to every village and pueblo of the country; to establish training schools for developing men who can carry on the reconstruction work that faces the country. Mexico is beginning to realize to-day that the failure of the Madero revolution is to be found in the lack of organization among a people, and if the present attempt is to succeed it must fill this void which is the origin of military intrigue, cuartelazas, foreign machination and a goodly part of the menace of intervention.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Zapata Die Fighting, Wikiquote

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-July 1920

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/07/v3n07-w28-jul-1920-liberator.pd

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From The Liberator: “The Mexican Revolution” by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman, Part I & Part II

Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_Revolution

Álvaro Obregón Salido, 1880-1928

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81lvaro_Obreg%C3%B3n

Emiliano Zapata, 1879-1919

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

Plutarco Elias Calles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plutarco_El%C3%ADas_Calles

Tag: Cananea Massacre of 1906 Massacre of 1906,

https://weneverforget.org/tag/cananea-massacre-of-1906/

Tag: Bisbee Deportations of 1917

https://weneverforget.org/tag/bisbee-deportation-of-1917/

The Bullitt Mission to Russia:

Testimony Before the Committee on Foreign Relations,

United States Senate

-by William Christian Bullitt

B.W. Huebsch, 1919

https://books.google.com/books?id=8eURAAAAYAAJ

Felipe Carrillo Puerto

https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/carrillo-puerto-felipe-1874-1924

Benito Juárez

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benito_Ju%C3%A1rez

Antonio Irineo Villarreal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Irineo_Villarreal

Photo: President Alvaro Obregón & Cabinet Members

-General Antonio I. Villarreal, Minister of Agriculture and Development

http://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/fotografia:438703

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Juana Gallo – Songs of the Mexican Revolution