———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Friday July 30, 1920

“The Mexican Revolution” by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman, Part II

From The Liberator of July 1920:

The Mexican Revolution

By Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman

[Part II of III.]

There have been a great many myths regarding the benefits of the Carranza régime, such as the opening of schools, giving lands to the Indians, nationalizing the sub-soil, etc., etc. One by one the pitifully few schools of the Diaz administration have been closed until Tacubaya and Mixcoac, two of the largest residence suburbs of Mexico City cannot boast a single public school. Land, given to the Indians, has in many cases, as in Yucatan, Tabasco and Morelos, been wrested away by military might, while a single grant to a General has often amounted to more in area than all the lands given away to the people during the whole of the Carranza rule. Under the cloak of the slogan of Mexico for the Mexicans, which has so attracted the imaginations of American radicals, he has stabbed every liberty in the back, and has built up a grasping, grafting, unprincipled military clique, the members of which have ridden across the land looting, murdering and stirring up revolt, until the federal soldier is more feared and hated than the bandit.

Directly the revolution resulted from two things: the attempt on the part of the government to railroad Bonillas, former ambassador at Washington, into the presidency; and the attempt to repeat the story of Yucatan and its murders in Sonora, the home state of Obregon.

To guarantee the election of Bonillas, government candidates were imposed by force in half a dozen states, Obregon meetings were broken up by the sabers of the man on horseback, Obregon himself was arrested on fake charges of inciting a rebellion. The knowing shook their heads, and predicted his murder within a week or two.

In the meantime Carranza was pouring soldiers into Sonora, against the repeated remonstrances of Governor de la Huerta, to crush the railroad strike and several mining strikes that were on, and probably in addition to break up the state government and impose his own officials as he had done in Yucatan, in Tabasco, in half a dozen other states.

Obregon saw that the time to act had come. To do so, he had to escape from the sleuths that hounded him day and night. This was difficult as he is well known and easily recognizable because of his having lost an arm in the battle of Celaya. One night he held a conference with General Gonzalez at the Chapultepec Cafe on the edge of Chapultepec park. About eleven o’clock his party left in their machine, but instead of returning to the city took a spin about the park. The sleuths in autos followed close behind. In the shadows of the park Obregon changed the big sombrero he always wears with the smaller felt hat of one of his friends, and, watching his opportunity, jumped from the slowly running machine behind a hedge. The auto proceeded on its way, and returned to Obregon’s house. Apparently Obregon left the car, and his friends called “Good-bye, Alvaro,” as the machine swept away from the curb. The sleuths did not become suspicious until the following day.

Meanwhile Obregon went to an appointed spot in the park where a railway worker met him with a big cloak. They went to the latter’s house, where they waited until half-past four in the morning. Obregon slipped into overalls, tied a big, red bandana about his neck, picked up a lantern and with his friend sallied forth to the station. In spite of his missing arm, he passed two guards, with a cheery “adios,” and a swing of his lantern in their faces to blind them, and jumped on the waiting train. An express agent concealed him in his car, and he was off to Michoacan.

In Michoacan the banner of revolt was easily raised. The governor of the state rushed to his side with troops. The Yaqui Federals, all his friends, deserted. Within a week he had thousands of armed men at his disposal.

Obregon fought his way down from Sonora, through the states of Sinaloa, Nayarit, Guadalajara, direct to Mexico City in the tragic Huerta days of 1914. He is an impulsive, determined, Rooseveltian type of man, but with a social consciousness. There are many stories afloat regarding his hasty actions when he governed the city of Mexico towards the end of 1914. An American told me with horror that he even made the owners of fashionable shops on Francisco I Madero Avenue, get out and sweep the streets during the days when the city was without street-cleaners.

“Why, that is Boishevikeeeeeeee,” she cried, and agreed with her.

It is certainly true that he did not mince matters with the food speculators. He called the owners of all stores and factories together one day, and told them, General Hill acted as his spokesman-first, how they were to treat their employees; second, that any dealer caught speculating in the necessities of life would be taken out in the plaza and shot. The harshness of this is not so apparent when the truth is told that the food merchants were running the prices up to fabulous figures. Poor people were dropping dead on the streets from starvation, and every morning their bodies were run out of the city on a flat car and burned. The merchants answered his declaration by closing up their shops. Obregon then told his soldiers and the people to go help themselves. He might have made a more intelligent solution of the problem, but the incident shows the temper of the man, and in any event, food-stores have ever since been a bit careful about boosting their prices. When the rebels entered the city on May 1 under General Trevino his first edict was to the effect that all legitimate business and industry might continue operation without fear of molestation, but that all speculators in food stuffs would be drastically dealt with.

Very early Obregon began to doubt the good faith of Carranza, who showed no inclination to enforce the Constitution of Queretéro, which contains the most enlightened labor code of any capitalist country; who manifested no desire to satisfy the agrarian claims of the states south of Mexico under the revolt of Felix Diaz, and Mixicuero. One day Obregon left his post as Secretary of War and accepted the job of mayor to the little village of Kuatabampo in Sonora. The act was typical of the impulsive man.

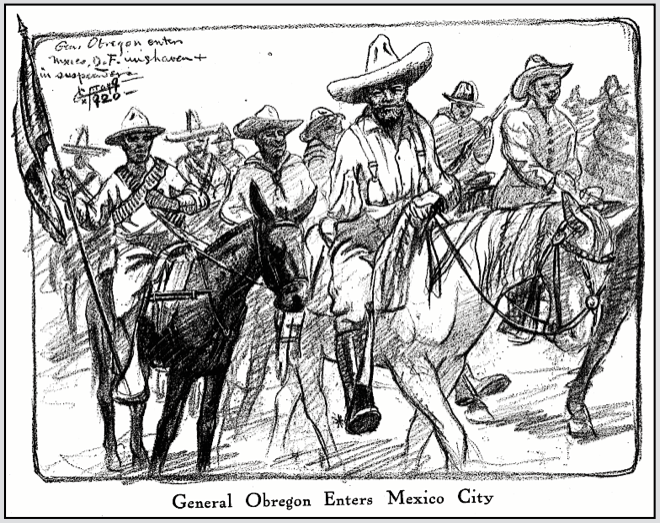

Last Sunday he rode into Mexico City at the head of twenty thousand rebels between the crowds that jammed the road from the suburb of Tacubaya to the capital. He passed up the fashionable Paseo de la Reforma with a six days’ growth of beard, wearing an old shirt and SUSPENDERS. He has taken a shave since his arrival, but he still wears the suspenders about the capital-and the same shirt. We are all hoping he has another and will take a change soon.

Obregon is the idol of the lower classes. Yet he has few of the ingratiating tricks of the professional politician. As he passed through the cheering multitudes, he rarely bowed or smiled, or gave the slightest sign of recognition.

At the caballito, which is a great iron statue of Charles the Fourth, at the big circle which marks the junction of the Paseo de la Reforma and the Avenida Juarez, in the amphitheatre made by the great Heraldo de Mexico Building, the American Consulate, the St. Francis Hotel and the Foreign Relations Building, Obregon made a few brief remarks-he is not a speech-maker-changed his horse for an auto and hurried up to the National Palace. As he entered the Zocalo, the broad National Plaza, beside which stand the City Hall, the Capital Building and the great Cathedral, the peons who had crowded up into the balconies of the latter began ringing the great brazen bells. All afternoon and evening they flung the sonorous, heavy sounds across the flat-roofed city. But Obregon did not stay to receive homage, rushed past in the auto, with a salute to Gonzales, who had been talking for a wearisome length of time, shouted half a dozen sentences to the crowd, and was gone, a band of Zapatista cavalry pounding hard behind in attempt to keep up.

Obregon has learned much since he entered Mexico City in 1914. Six years added to a man’s life when he is in his thirties, six years full of experience and action, mean everything. To-day Obregon is probably as determined to put his ideas into practice as he was when he took up arms against Huerta, but he has seen the folly of following certain courses. His manifesto, issued in Michoacan-and this will come as a shock to American radicals, although Carranza made the same statement in trying to get American recognition-declares, that foreign capital will be given every protection and guarantee, and that its holdings will not in any way be molested. But whereas Carranza made this statement and, did not keep his word, Obregon is determined to make good the declaration, and for the following reasons: Mexico cannot put across one measure of real social reconstruction if the government has the opposition of American capital.

On the other hand, Mexico is the richest land on the face of the earth so far as resources are concerned. That is her worst crime. She would ere this have been peaceful and prosperous had her people had to struggle for their existence against the barrenness of the soil. But Mexico is so rich, and her resources so unexploited, and those in the hands of foreign capital so little in comparison to the total wealth, that Mexico can afford to say to foreign capital:

Keep what you have. With the remainder we shall build a modern social edifice, we shall give lands to the people, we shall establish schools, we shall teach our people to organize themselves into labor unions; we shall carry the real meaning of the revolution to every pueblo, until we leaders shall have such an enlightened backing as not to fear the instigated revolts of foreign capital. If we give land to the people, the surplus labor supply will be cut down, for the Mexican is instinctively, fundamentally agrarian. Foreign capital will have to pay decent wages to get workers.

This may be wrong reasoning. But the Mexican stands eternally in the fearful shadow of armed intervention. He knows that it would take very little to precipitate it. Should he institute a real social revolution such as we have witnessed in Russia-and that is impossible because the people are not organized for it-intervention would come with the suddenness of their own tropic storms. Such a social revolution would perish in blood and iron, militarism would again be in the saddle in the United States, another India would be born, with a more tremendous race problem to solve than exists to-day in the south.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Zapata Die Fighting, Wikiquote

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-July 1920

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/07/v3n07-w28-jul-1920-liberator.pd

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From The Liberator: “The Mexican Revolution” by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman, Part I

Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_Revolution

Álvaro Obregón Salido, 1880-1928

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81lvaro_Obreg%C3%B3n

Emiliano Zapata, 1879-1919

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Corrido del General Álvaro Obregón