~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Thursday June 6, 1918

New York, New York – The Masses Trial as Told by a Defendant, Part II

The trial of the those connected with The Masses began on April 15th of this year and resulted in the dismissal of the jury on April 27th, for failure to agree on a verdict. Another trial of the defendants is certain, according to the prosecution. Floyd Dell, one of the defendants, tells the story of that trial wherein the defendants were facing up to twenty years in prison for alleged violations of the Espionage Act of 1917. We began with Part I yesterday and conclude today with Part II.

The Story of the Trial [Part II]

By Floyd Dell

Speech of Dudley Field Malone

[Said Mr. Malone:]

This is a case of large issues-issues which go to the very source and purpose of our Government. And so I would like to read to you very briefly a historic statement of these issues-for these things have been spoken with classic utterance, and doubtless you would rather hear them from the original sources than from me-in order that you may have in your minds certain fundamental considerations in reaching a verdict and a judgment in this case.

In I792, Thomas Erskine defended one of the signers of our Declaration of Independence for printing a book-the “Rights of Man.” Thomas Paine had written that book, and it was being defended, and at that time Erskine laid down certain fundamental propositions from which flow the liberties of the press in all English-speaking countries.

Erskine said: “Every man not intending to mislead and confound, but seeking to enlighten others with what his own reason and conscience, however erroneously, may dictate to him as truth, may address himself to the universal reason of a whole nation

And that is the basis, gentlemen, that is the crux thought, underlying the freedom of the press. If anyone in this country has the power to say by autocratic power that a certain thought, because he disagrees with it, shall be taken out of the public discussion, there will no longer be a free expression of opinion.

Erskine said further, speaking of Paine-and he disagreed entirely with the opinions of his client, he did not agree with Paine’s views at all-“His opinions indeed were adverse to our system, but I maintain that opinion is free and that conduct alone is amenable to the law.”

I hope you will take that as the crux idea in this case in formulating your judgment-that opinion in a democracy like ours, must be free freely spoken, freely written. Only conduct is amenable to law.

“When men,” said Erskine, “can freely communicate their thoughts and sufferings, real or imaginary, their passions spend themselves in air like gunpowder scattered upon the surface; but pent up by terrors they work unseen like subterranean fire, and burst forth in earthquake and destroy everything in their course. Let reason be opposed to reason, and argument to argument, and every good Government will be safe.”

And, gentlemen, this is not only the opinion of Erskine. It is the opinion of one of our contemporaries. It is the opinion of a man whom I consider and have considered for the past eight years the greatest statesman this republic has yet produced-in his vision of international affairs, in his conception of democracy, and in his desire that America should take a permanent place among the nations for a democratic and permanent peace-and that is our President. And what does our President say on the subject of agitation? In his famous book on constitutional government, he has a sentence which is very illuminating: “We are so accustomed to agitation, to absolutely free outspoken argument for change, to an unrestricted criticism of men and measures carried almost to the point of license, that to us it seems a normal, harmless part of the familiar processes of popular government. We have learned that it is pent-up feelings that are dangerous, whispered purposes that are revolutionary, covert sallies that warp and poison the mind; that the wisest thing to do with a fool is to encourage him to hire a hall and discourse to his fellow citizens. Nothing shows nonsense like exposure to the air; nothing dispels folly like its publication; nothing so eases the machine as the safety valve.”

And that is the thought I want to give you in the very beginning, that even if these defendants spoke folly, that even if they spoke nonsense, they had a right to the expression of their opinion, as long as they did no single act-as they never had the intention to commit an act-which would be a violation of the law.

We are charged here with conspiracy. If each one of these defendants here today whose testimony you have heard, himself was guilty of an individual violation of the law, but if they never met together, never thought together, never concerted together, never conspired together, then there is no conspiracy.

Where is the conspiracy in this case? I feel I have had some experience with the United States Government, in its service. After a year as Assistant Secretary of State in Washington, and four years as Collector of the Port of New York, with all the anxieties over the care and protection of those thirty-one German “and Austrian ships; hunting real spies, real German propagandists-not American citizens with patriotic motives seeking to form a constructive program-I feel I know something about the power of the Government of the United States.

The Government of the United States has over one hundred and fifty thousand detectives under the Department of Justice, under the Treasury Department, and in the Intelligence Office of the Army and Navy. All this power-all this force of investigation has been at the disposal of the prosecution-the Government. And, in addition to all that, the prosecution has ransacked the files of the defendants.

This has been the opportunity the Government has had to prove its case. And where has it proved a conspiracy? Where is there a single letter written from one defendant here to another, on the subject of this conspiracy? Where is there proof that they had a single conversation? Where is there proof that they ever matched their minds on the subject?

Did these men ever intend to advise violation of any law of our Government? You saw them on the stand. You heard them. Can you imagine Art Young, good-natured old Art Young, looking like nothing so much as a comfortable Newfoundland dog, conspiring to overthrow the republic ? Why, gentlemen, it is not reasonable. Art Young, forty years in public life, known to public men of political parties, a pacifist because he loves mankind and knows that war is a hellish proposition, but a man who never had a disloyal thought in his life.

Art Young hates war. Yes. But is it possible for you to go back in your memory to the days in which this war began? Is it possible for you gentlemen to put yourselves in the frame of mind in which people generally were when war was declared? Why, in the last campaign the great issue-the great issue upon, which President Wilson was elected President of the United States, was that he kept us out of war. That was the great issue. I know it was the great issue, because I went from New York to California twice on that issue, and I know that the West was carried on that issue, and I know that the West carried the election and he won by two million votes. In those days we all hated war.

And yet, gentlemen, I am no pacifist. A man of my blood and origin seldom is. But I have never felt that pacifists were criminal. I have never felt that pacifists do not have a right to speak their desire, to speak their hope, to speak their thought that we might maintain the country at peace, or that the world might stop this horrible madness of settling disputes by bloodshed.

The intent is the thing. And what did they do to show their intent? Did they, or did they not, show any desire to keep within the law? First of all, taking events in chronological order, a business manager, a young man-a Harvard graduate-what did he do? When his attention was called to the fact that an advertisement in the magazine might be unlawful, he went-to whom? To the only man in the Government anybody had any idea had anything to do with it. He went to the head of the Censorship Bureau. He went to George Creel.

Now what difference of opinion was there between Rogers and Creel, if you want to reach the truth of this? Rogers said he went to see him to get his opinion as to whether the advertisement in the magazine was lawful. Creel said that is what he came for, said that is what Rogers told him he came for. Creel says he did not pass upon the advertisement because he had no right to do so, but that he told Rogers there was no law covering such matters. He glanced through the magazine; he did not agree with some expressions concerning the war, but, as he told Mr. Hillquit, he saw nothing in it that was against any existing law. He told Rogers that it was a matter for the Postoffice Department.

Rogers came to the Government for advice. If these defendants were conspiring, gentlemen, to violate the law, would one of them go to Washington, to the head of the Censorship Bureau, to ask his opinion whether they were violating a law?

And what was the next thing they did? Gilbert Roe, Mr. Eastman’s attorney, called his attention to a passage in the June number, which had been published before the passage of the Espionage Act, and advised him that it might be construed as a violation of that law. And what did Eastman do? His testimony is uncontradicted by the Government, and it is supported by Rogers. He told Rogers to get all the copies of the June edition that were on hand, and gather them together so that there would be no further distribution of them. And Rogers, to make sure they would not get into circulation, took them up to his own home and locked them up. Was that an attempt to conspire? Or was that an attempt to keep within the law as soon as they had half an idea of what the law was? That is the second point in their attempt to conform to the laws of the Government.

And then in regard to this circular that Rogers drew up. In that circular he reprinted an article by Max Eastman from the June issue, and sent it out to 40,000 people; but he cut out the paragraph referred to above, because he had heard that there was some possibility of its being construed as a violation of the law. If he were trying to conspire to oppose the law, would not he have left that paragraph in? Would he have taken it out?

And what was the next thing that these men did? In July, Max Eastman began to communicate with the Postmaster General-for what? To find out from Mr. Burleson how they could write their magazine so that it would come within the provisions of the regulations of the Postoffice Department and the law. If you were conspiring to do something, would you be showing a Government officer what was in your magazine? Would you go to the Postmaster General, a member of the Cabinet, and show him the magazine, if you were conspiring in the magazine, or if you thought you were? Their intent was to conform to the law to the best of their ability.

What was the fifth thing they did? When the magazine was suppressed, they went to court. They went to court to sustain their rights, because they believed they had not violated the law. And Judge Learned Hand, another judge of this court, handed down a decision in which he held that these defendants were entirely within their rights and that the Postmaster had exceeded his rights in suppressing the magazine.

If they had been conspiring, would they have brought such proceedings?

What was the next thing done? Mr. Eastman wrote to the President of the United States. He brought the Masses to the attention of the President.

Why, gentlemen, if he had been conspiring, would these men have gone to the President, to Creel and to Burleson, and into court?

I don’t believe there ever was a case in which by the actions of the defendants themselves they showed so definitely their intention to violate no law.

Don’t we want thinkers in the country? Don’t we want them to think clearly? The President says we do. The President says it is most important in a constitutional government that we should have clear thinking. He says, “The vigilance of intelligently directed opinion is indeed the very soil of liberty, and of all the enlightened institutions meant to sustain it. And that will always be the freest country in which enlightened opinion abounds, in which to plant the practices of government. It is the quintessence of a constitutional system that its people should think straight, maintain a consistent purpose, look before and after, and make their lives the image of their thoughts.”

Men of all parties and all creeds in this country have a right to express their opinion during the war, as well as before the war. Why? Because if we are to have a permanent peace, it must be a just peace. There must be no annexations. There must be no indemnities. Every people must be free to determine their own form of government.

And men in this country, like Max Eastman, and myself, openly spoke and urged the President to state our war aims, the terms on which we would make peace. We did it with no disrespect. We may have done it in a militant fashion, but we did it because we felt that America, the leader of democratic idealism in the world, ought frankly to state her terms of peace, her war aims, since we had nothing to hide.

And months afterwards, the President announced these war aims and these peace terms, in a document which has fixed the performance of the Allies. Is a man to be charged with crime for thinking things which the President said six months after?

Can it be that even in war days, when we are trying to unify our nation, when we are trying to gather together every element of our people behind the government, that we are going to hold guilty of conspiracy on evidence of this kind, American citizens of this stamp? Are we going to shackle the creative thought of the nation?

Morris Hillquit’s Speech

Morris Hillquit, in the final speech to the jury on behalf of the defendants, said:

Now there has been a great deal of talk as to whether or not the magazine had a policy. The importance of the issue has become exaggerated. The magazine has not had a policy in the sense of a political program. That clearly appears from the announcement published in every issue of the magazine. But did we mean to say that the magazine had no distinct character? By no means! The Masses was a radical magazine. It was a radical magazine because it was created by radicals.

That radicalism expressed itself before our entry into the war always in the same way, by the expression of independent thought, free, individual, honest expression, on any subject that was broached by the magazine.

And then, gentlemen, the war came on. First the European war, then our entry into it. And what is the testimony with reference to both phases? When the war broke out in Europe, as far as the testimony shows, the vast majority of the contributors of the magazine favored the cause of the Allies. Max Eastman was included in that number. Floyd Dell was included in that number, and their very explicit statements to that effect were read to you. They were published openly. They were published broadcast.

Then new developments occurred from day to day, from month to month. After the war had been in progress about a year or more, the desirability of “crushing” Germany became doubtful. Thoughtful men here and elsewhere all over the world pointed out that we had seen the result of “crushing” a defeated nation when Prussia in 1870 took Alsace-Lorraine from France and that deed, that crime of 1870 had now thrown the entire world into another war such as mankind had never seen before.

Shall this war be conducted for similar aims? Shall other countries be dismembered? Shall other nationalities be divided? Shall territory be annexed? Shall indemnities be imposed? Shall this war leave a smarting feeling of grievances among nations which might lead to greater and greater wars and end in the extermination of our entire civilization?

There were men,-and thoughtful men, who said: This great evil having come upon mankind, the only adequate compensation possible is that this war should be the last of all wars-that it should not end in rancor, in resentment, in seeds of new war, but that it should create a new world system, based on true democracy, and true justice, and absence of any and all causes of war.

And, gentlemen, it was the President of this Republic at that time who better than any other man, I believe, in the world, expressed that thought-that desire-that idea in a most memorable speech made before the Senate of the United States in January, 1917.

We have been mentioning the name of the President very often in this case. Don’t think for one moment that we wish to hide behind the President. We refer to the President, first, because, as the Executive Chief of this nation, he is the spokesman of the nation. We refer to him, second, because he has been all during this war an intellectual thinker on the war, and has had a peculiar, exceptional facility of expression. But mind you, gentlemen, we claim that~ the humblest citizen in the United States has the same right to do his own thinking on these world problems and to express them as the President of the United States. That is the essence of democracy-the sovereignty of the people. So, please don’t misunderstand our reference to the President of the United States.

I say, then, that in this memorable speech of January, 1917, the President of the United States gave a new chart to mankind. He proposed a new world which had for its foundation the ending of this present war without victory, without defeat, without humiliation, without intrigue, without causes for new wars.

And Max Eastman and Floyd Dell testified that they were among the thousands who accepted that program enthusiastically, passionately, and they advocated it in the pages of the magazine, and on every other occasion.

Then came the announcement of the policy of unrestricted warfare by the German government. Our country went into the war-for what? For any gains of our own? No. Because this country was actually physically endangered or menaced? No. But “to make the world safe for democracy.” What does that mean? To bring about exactly the state of affairs the President had depicted in January, 1917, and nothing else.

The President of the United States had come to the conclusion that the only way to bring about this state of affairs was by joining in the war and throwing the weight of our arms, the weight of our resources, on the side of our Allies.

A short time before that he had thought we could accomplish the same object by staying out of the war, by remaining the most powerful neutral in the world.

Now Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, and a great many others, still believed, as the President and others had believed before our entry into the war, that this object-the object of ending the war, the object of ending all wars-could be best accomplished by our staying out of the war, and by our using the tremendous power of this country as a neutral, in influencing, and if possible, directing both sides.

Gentlemen, this does not represent a conflict of opinion between Max Eastman and the President of the United States. It represents a difference of opinion between two groups of thinkers, each reasoning from his own honest convictions.

It is an hypothesis in both cases. One is a possible policy; the other is a possible policy. We are not here to defend or to prove the position of Max Eastman or Floyd Dell, or the correctness of their position. They may be all wrong. They may be all right. We don’t know. All we say to you is this, that it was an expression of honest conviction. All we say to you is that expression was prompted as it was in the case of all our patriots, by a desire to bring about the best ends for the country, and for mankind at large.

We had a right to entertain such views. We had a right to entertain them even though we were in the minority. We had a right to entertain them, even though they were contrary to the views adopted by the official administration of the country.

And that brings us to another subject-the subject of conscription. There was a good deal said about the attitude of the writers in the Masses on the subject of conscription, and on the somewhat related subject of conscientious objectors.

Gentlemen, we want you to understand our position. Before the Conscription Law was enacted, a great many of the contributors of the Masses were opposed to it. We need not go into it much longer. As far as the system itself is concerned, it was novel to this country. It was a radical departure from established policies. And for this reason there were many sections of the people who were opposed to it. It was debated in Congress. Mr. Barnes showed you the figures. He showed when it finally passed the House of Representatives, there were only, I believe, twenty eight members who voted against it. Yet you will all remember that in the debates preceding the taking of the vote, there were very large numbers of Congressmen expressing themselves in opposition to it. You will remember that when the bill was first introduced, there was a very grave question whether it would pass at all or not. You remember that in various straw votes taken before the bill was passed, the two sides showed almost equal strength.

The Administration prevailed. The bill was passed. The bill was passed by a large majority. But don’t forget that there was a strong opposition to it at the time from all quarters of the country.

And these defendants, or some of them, were among the millions of American citizens who opposed the system of conscription, and they voiced their opposition in the pages of this magazine, just as you or anybody else who was opposed to it would voice it in this manner of expression in private talk.

When the war came upon us, it could not over night have changed the psychology, the attitude, the ingrained habits of men. This was a matter of gradual growth. At the time when we voiced our opinions against conscription, we did it when conscription was not a law, when the principle of conscription was debatable, and when the right of every man and woman to express his or her opinion on the subject was freely recognized by the entire world. Today opposition to conscription acquires a certain sinister significance, particularly in the mouth of the prosecuting counsel. Gentlemen, at the time these articles were issued, the phrase “opposition to conscription” was absolutely common. All newspapers bristled with it. It was considered perfectly legitimate.

Now we have in this phrase “opposition to conscription” two different meanings, as expressed in the magazine. There was one opposed to conscription as conscription, as a system; and there was the other so well expressed by Floyd Dell, for instance, when he said, “Personally, I was not opposed to conscription. I recognized that in modern wars conscription is the only method of raising armies. But I want a democratic conscription, a conscription of the willing, again to use a phrase of our President, and I said that any such conscription must be based upon one definite principle: and that is, if there is any person whose conscience will not allow him to take up arms, who could only do it in gross violation of his soul, he should not be compelled to take up arms.” Or if he is sought to be compelled, and he still cannot make it compatible with his conscience, he should be allowed to take his punishment for refusal to serve, and be treated with some consideration some dignity-not to be treated as a slacker or coward, not be derided, not be held up to the contempt of his fellow men. The government should mete out his punishment, as Mr. Eastman expressed it, with a sort of “sorrowful dignity,” recognizing the necessity to inflict punishment for the maintenance of discipline, but recognizing at the same time that that man is not a degenerate, not a coward, not a slacker, but a man of honest convictions.

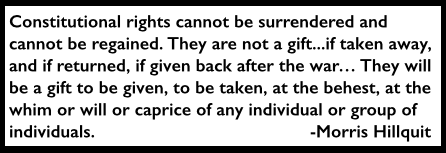

There are two other kinds of articles or cartoons to be considered here. One is a general expression of the struggle to preserve the democratic institutions during the war. Now, gentlemen, on this point you don’t have to agree with the defendants, but you should understand their point of view. And this it was, as expressed in these articles. They said, “We are engaged in war. We accept the war as a fact,” as Mr. Creel, for instance, phrased it. But we want this war to be fought as a war for democracy. We all want it. We don’t believe that this war can be fought for such purposes unless we first preserve and strengthen our own democracy. We don’t believe in abandoning the fundamental constitutional rights of this country, even during the war, even for a day, even for an hour. For, gentlemen, these constitutional liberties once surrendered for one single hour, mean a destruction of the very foundations upon which this republic was built.

Constitutional rights cannot be surrendered and cannot be regained. They are not a gift. They are the conquest by this nation, as they were a conquest by the English nation. They can never be taken away, and if taken away, and if returned, if given back after the war, they will never again have the same potent, vivifying force of expressing the democratic soul of a nation. They will be a gift to be given, to be taken, at the behest, at the whim or will or caprice of any individual or group of individuals.

And finally, there is another series of articles and cartoons which we may classify as a general opposition to imperialism in any form, at home or abroad, and to capitalism in the sense of profiteering in the sense of allowing a privileged, powerful class to take advantage of this crisis and to capitalize the suffering of their fellow men, to capitalize this great strain upon the nation for their own individual advantage or advancement.

Now, gentlemen, I have tried my best to classify all of these articles-pictures and cartoons-and I will ask you when they are read to you or shown to you again, to ask yourselves this question: Does it do any more than express one of these sentiments? And it does not matter how violently it may express that sentiment, and it does not matter in what bad taste, from your point of view, it may be expressed. That is a matter for the author. That is a matter of literary criticism. That has nothing to do with the case.

And then I want you to bear in mind, gentlemen, after all, that all of these matters, interesting and instructive as they are, have very little to do with the case. If a stranger had walked into this courtroom while this case was in progress, if he had not read the indictment, if he had not known about the specific charge, but just listened to the testimony, what conception do you think he would have of this case? Would it ever occur to him that this is a trial of four men charged with having plotted, conspired together, to commit a definite crime under the statute, to obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service? No. He would say, this is a very interesting discussion between two conflicting views on war and peace and incidental subjects. He would consider it a highly interesting debate. But, gentlemen, this is not a prize debate. This is not a contest of wits. And you are not sitting as judges of a debate here.

I cannot impress it strongly enough upon you that your verdict has absolutely nothing to do with the approval or disapproval of the views of these defendants. A verdict of not guilty will not mean that you endorse their views, or any part of them. That is your own private affair. You may endorse them, you may oppose them most violently. But that has nothing to do with your verdict.

Gentlemen, about the greatest disservice you could render to the community, to your country, to the system of justice which is the cornerstone of the entire national existence of America, would be to render your verdict upon the assumption that you are demonstrating your patriotism by a verdict of guilty, and upon the assumption that there would be any sort of reflection upon your patriotism by a verdict of not guilty. Your patriotism is not on trial. Your views are not on trial. You have no right under your oaths to be guided by such considerations at all in the slightest degree. Just in these times, gentlemen of the jury, when tension is high, when feelings run high, when hysteria becomes dangerous, it is most important that this atmosphere should not be carried into our halls of justice.

You have been placed in an exceedingly delicate and important position. You are here to uphold the majesty of the law. You are here to uphold the principle of justice in spite of popular clamor. You are called upon to pass upon the guilt or innocence of your fellow men upon the evidence in this case.

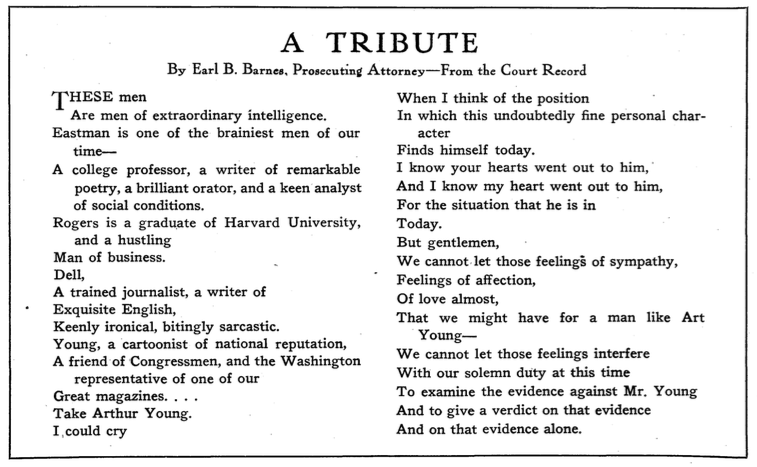

Mr. Barnes

In the afternoon of Thursday [April 25th] Mr. Barnes summed up the case for the prosecution. There was one odd thing about his speech. For all his earnestness, his apparently sincere belief that what we had done constituted a crime, he was not what one would call an eloquent speaker; and yet, strangely enough, a note of real eloquence came into his voice whenever he talked about us-whenever he referred to us not as defendants in the abstract, but as persons. Could it be that really in his heart, and in spite of his conscious legal persuasions to the contrary, he instinctively considered us simply as a crowd of good fellows with whom he would like to be in agreement? He went out of his way to pay us compliments which seemed utterly sincere. Especially he seemed genuinely troubled at having to ask the jury to convict Art Young. But if such were his inner feelings, his sense of duty was stronger. We were all the more dangerous, he told the jury, because of our high abilities. He read, with sinister emphasis, while the band played patriotic airs outside and the newsboys cried the latest defeat in France; every line which could suggest to the jury that our hearts were not with our country in her hour of struggle. He wrenched phrases from their context, juxtaposed irrelevant bits of testimony, paraded gravely meaningless fragments of evidence, reiterated dark surmises which his common-sense must have told him were hollow, misrepresented our testimony on certain points to the jury, played upon their prejudices against Socialists and pacifists, tried to drag in the red spectre of Anarchism, conjured with soldiers’ blood and parents’ tears, and tried to persuade the jury that they could only prove their patriotism by sending us to prison-in a word, he did his duty, as it is currently understood, as a prosecutor in behalf of the people of the United States. And yet when he spoke, as he did sometimes, of liberty and of the rights of free speech, his voice rang clearer and more convincing, and there was a new look on his face…In such momentary flashes one gained the impression that he would have been a happier man, and inevitably a more able advocate of his cause, if he had been on our side…Preposterous fancy to entertain of a man who is doing his damnedest to get you sent to prison for twenty years! “And so, gentlemen of the jury, I confidently expect you to bring in a verdict of guilty against each and everyone of the defendants.”

The jury, being duly charged,* retired at 5:45 p. m., April 25th, Thursday. And we awaited their verdict.

–* Excerpts from the judge’s charge are given on page 35.

In the hands of those men lay our liberty and perhaps the liberty of the press in America henceforth. If this was a conspiracy, anything was a conspiracy, and the freedom of the press was to be only a historical memory. Those twelve men, locked up in a room a little down the corridor, had these issues in the keeping of their minds, their hearts and their consciences.

We thought a good, deal about-those jurors as we walked up and down the corridors, smoking and talking quietly with friends, through the long hours and days that passed so slowly thereafter. It is hard to tell what a man is like from a few brief answers to a few set questions. It was a species of lightning guesswork to decide, those first two days, what kind of mind and heart and conscience a man had-what malevolent prejudices, what weak susceptibilities to popular emotions, what impenetrable stupidities might lurk unseen behind those unrevealing, brief replies. “Are you prejudiced?” “Yes.” “Can you set aside that prejudice?” “Yes.” “Will you be guided by the evidence?” “Yes.” These may be the replies of a fool or a coward or a liar; they may be the replies of an honest man, open to conviction of the truth and steadfast as a rock in maintaining that truth against all opposition. We had to gamble on our first impressions of character and choose irrevocably. But as the days passed, we had learned more about those men-learned what we did not know before what kind of men they really were. One cannot sit hour after hour for nine days in the same room with twelve men, without getting to some extent acquainted with them. We knew, as well as if we had had long conversations with them, how some of them stood.

But that, too. was mere guesswork. How could we be sure that the man we thought most hostile might not turn out to be our best friend-perhaps our only friend? And those who were for us, could we be certain that they had the courage to hold out? Some experienced friend would come along and take our arm and whisper, “Expect anything.” From behind the heavy door of the jury room came sounds of excited argument…

After dinner we returned, with a few friends, and bivouacked in the dim corridor, waiting. At 9:35 that night the judge was sent for, and we went eagerly into the courtroom. The jury filed in. Had they brought in a verdict? No; they desired further instructions.

The judge repeated his definition of conspiracy, and the jury went back. And already the inevitable rumors began to percolate. “Six to six.”

Next morning the debate in the jury room grew fiercer, noisier. What was happening? At 12:30 the jury came in, hot, weary, angry, sad, limp and exhausted. They had fought the case among themselves for eight terrible and vehement hours. We were sorry for them. We could not complain that they had not taken it seriously enough. It was evidently impossible to arrive at an agreement. And so in fact they had come to report. But the judge refused to discharge them, and they went back again, after further instructions, with renewed grim determination on their faces.

And again the rumors floated about. One of those who stood for conviction on the first vote had gone over to the other side. Again we wandered about the corridors, and returned in the evening to camp outside the court-room. What was the jury doing? Rumor had it that a second had gone over to the other side…And then, in the unlighted windows of the Woolworth Tower opposite, we discovered a dim and ghostly reflection of the interior of the jury room. Men were standing up and sitting down, four or five at a time. A vote? Someone picked up something that looked like a magazine. Someone raised his arm. Someone strode across the room. Someone took off his coat. We crowded about our window and watched…and then went away. We had waited for twenty-nine hours. We could wonder no more. The whole thing seemed as dim and far away from us as that ghostly reflection in the window. We thought about stars and flowers and ideas and beautiful women…

Eleven o’clock-jurors reported disagreement-sent back.

Saturday noon [April 27th]: hopelessly deadlocked, the jury was at last discharged, with all our thanks. And so, outside!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-June 1918

Page 12-Part II: “The Story of the [First Masses] Trial”

-by Floyd Dell

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1918/04/v1n04-jun-1918-liberator.pdf

See also:

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday June 5, 1918

New York, New York – The Masses Trial as Told by a Defendant

From The Liberator: Floyd Dell Recounts The Masses Trial; Art Young Found Asleep in Courtroom

Morris Hillquit

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAhillquit.htm

George Creel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Creel

Espionage Act of 1917

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Espionage_Act_of_1917

Note: see Part I for links to more info on individuals involved in this case and for links to information on The Masses and The Liberator.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~