“For heaven’s sake, wake Art Young up,

and give him a pencil!

Tell him to try to stay awake

until he gets to jail!”

-Attorney Malone

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday June 5, 1918

New York, New York – The Masses Trial as Told by a Defendant

The trial of the those connected with The Masses began on April 15th of this year and lasted for about two weeks, ending in a hung jury. A new trial is certain, according to the prosecution. Floyd Dell, one of the defendants, tells the story of that trial wherein the defendants were facing up to twenty years in prison for alleged violations of the Espionage Act of 1917. We begin with Part I today and will conclude tomorrow with Part II.

From The Liberator of June 1918:

The Story of the Trial [Part I]

By Floyd Dell

AT 10:30 o’clock in the morning on April 15 we filed into one of the court-rooms on the third floor of the old Postoffice Building, and took our places about a large table in the front enclosure. Ahead was a table at which sat three smiling men from the district attorney’s office; higher up, on a dais, behind a desk, a black-gowned judge, busy with some papers; to the right a jury-box with twelve empty chairs; and behind us, filling the room, a venire of a hundred and fifty men from among whom a jury was presently to be selected.

It was with the oddest feelings that we sat there, waiting. It seemed strange that this court-room, this judge, this corps of prosecutors, those rows of tired men at the back, had any personal relationship to us. It took an effort to realize that we were not there as interested observers, but as the center of these elaborate proceedings.

It was more than strange, it was scarcely credible. Was it possible that anyone seriously believed us to be conspirators? Was it conceivable that the government of the United States was really going to devote its energies, its time and its money to a laborious undertaking, with the object of finding out whether we were enemies of the Republic! It was fantastic, grotesque, in the mood of a dream or of a tragic farce. It was like a scene from “Alice in Wonderland,” re-written by Dostoievsky. But it was true. We did not expect that the judge, frowning as he read over the papers before him, would suddenly look down at us over his spectacles and ask: “What the devil are you doing here? Don’t you know that I am a busy man, and that this is no place for silly jokes?”

No….For we knew that war produces a quaint and sinister psychology of fear and hate, of hysterical suspicion, of far-fetched and utterly humorless surmise, a mob-psychology which is almost inevitably directed against minorities, independent thinkers, extreme idealists, candid and truth-telling persons, and all who do not run and shout with the crowd. And we of the Masses, who had created a magazine unique in the history of journalism, a magazine of our own in which we could say what we thought about everything in the world, had all of us in some respect belonged to such a minority. We did not agree with other people about a lot of things. We did not even agree with each other about many things. We were fully agreed only upon one point, that it was a jolly thing to have a magazine in which we could freely express our individual thoughts and feelings in stories and poems and pictures and articles and jokes. And when the war came we were found still saying what we individually thought about everything-including war. No two of us thought quite alike about it. But none of us said exactly what the morning papers were saying. So–

We rose to answer to our names: Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Merrill Rogers, Art Young, Josephine Bell*-a poet-philosopher, a journalist, a business manager, an artist, and a young woman whom none of us had ever seen until the day we went into court to have our bail fixed. And there was another, invisible “person” present, the Masses Publishing Company, charged, like the rest of us, with the crime of conspiring to violate the Espionage Act-conspiring to promote insubordination and mutiny in the military and naval forces of the United States and to obstruct recruiting and enlistment to the injury of the service. We all sat down, and the trial had begun.

*John Reed, war-correspondent, and H. J. Glintenkamp, artist, also indicted, were not on trial

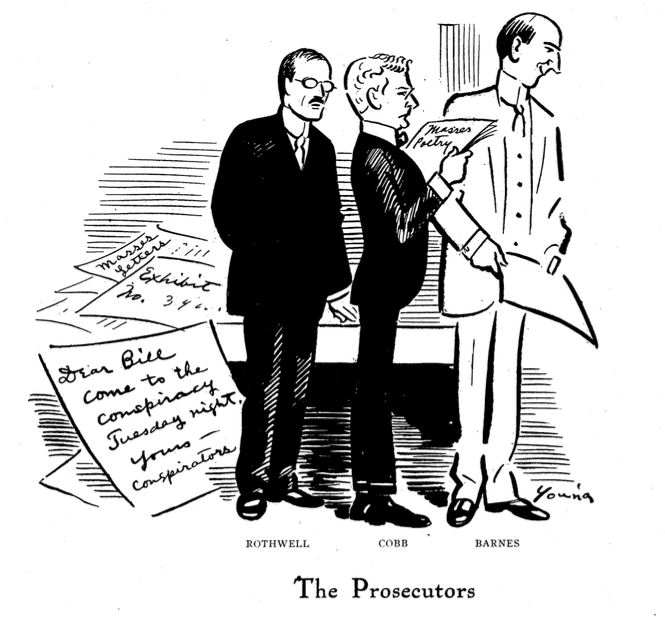

Our liberties, to the extent of twenty years, and our hypothetical fortunes to the extent of ten thousand dollars apiece, and beyond all this, we felt-the rights of all American citizens to a free press, and the honor of the United States-were now committed into the care of something entitled the United States District Court, Southern District of New York: something unfamiliar and in part mysterious to us, but with certain discernible elements of which we now began to take stock. On the bench was Judge Augustus N. Hand, a rather slender and slightly grizzled man of reassuringly judicious and patient demeanor, in whom we could observe no indication of any animus, and who showed a genuine interest in the case before him. In charge of the prosecution was Assistant District Attorney Earl B. Barnes, a very thin and angular man with a perpetual sharp smile; it was apparent that he would send us to jail, if he could, in the most good-humored way possible, as a matter of duty and with no personal grudge. He was assisted by two affable young men, Mr. Cobb and Mr. Rothwell. These were the tangible forces arrayed against us. But ranged invisibly on their side were the newspapers with their screaming headlines of Allied defeat, the militant tunes of a Liberty Bond band in the park beneath the windows, and the vast imponderable force of public feeling, stirred by the desire to “do something” and carefully taught by the newspapers to do it to people like us.

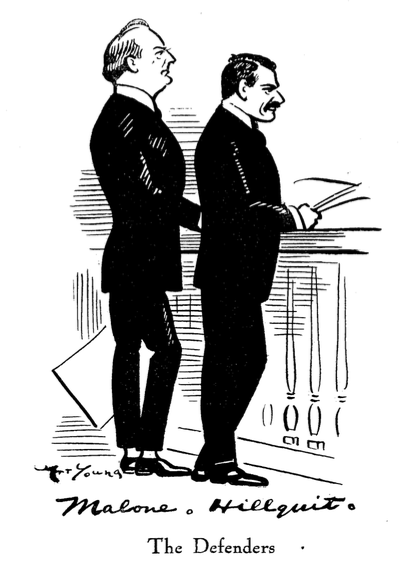

On our side were certain constitutional rights, legal precedents and safeguards, and the knowledge of our own innocence-all, except the last, already beginning to seem to us pretty thin and insubstantial to rely on in times like these. But as they faded, two figures, previously thought of more as friends than as defenders-too warmly human in our thoughts and affection., to be regarded until this moment as lawyers-emerged as the solid bulwark of our confidence: Morris Hillquit, Socialist candidate for mayor of New York in the last election, and a figure of note in the international Socialist movement; and Dudley Field Malone. Mr. Malone’s appearance in this case was as characteristic as his recent resignation of the position of Collector of the Port of New York, as a protest against the refusal of the Democratic party to fulfill its pledge to enfranchise the women of the nation, and against the brutality which the administration permitted to be inflicted on the suffragists at Washington. A man of the most warm-hearted and generous devotion to principle, gifted with passionate and eloquent speech, and with a remarkable power of synthetic argument, he gave these abilities once more, and magnificently, to the service of an unpopular cause in this trial. Morris Hillquit, cool, unshakable, resourceful, with a tremendous dynamic quality behind the relentless workings of a keenly logical mind, amazingly able to make clear and plain the difficult subtleties equally of law and fact-these were such defenders as we felt would secure for us the utmost consideration that the times could yield.

The jury box filled up, and under the questioning of defense and prosecution was sifted out again and again. A federal jury panel appears to consist chiefly of real estate agents, retired capitalists, and bankers, with a sprinkling of managers, foremen and salesmen-never a wage-worker. It is composed almost entirely of very old men, with only here and there a member of one’s own generation. It frankly admits an extreme prejudice against Socialists, pacifists and conscientious objectors, though it frequently asserts cheerfully that such prejudices will not stand in the way of an impartial consideration of the evidence…The selection of a jury occupied nearly the whole of two days, and of the twelve men finally accepted by both sides, nearly all admitted a prejudice to begin with. It was necessary to rely upon some fundamental sense of justice which we could only hope they possessed.

But, after all, we hoped to spare those twelve men the trouble of hearing the case. We hoped so, because we had reason to believe that there was no case to hear-in a very precise legal sense, no case whatever. On the ground that the indictment did not contain averments of fact sufficient to constitute a crime under any laws of the United States, Mr. Hillquit moved that the indictment be quashed.

After argument, Judge Hand sustained the motion so far as the first count of the indictment was concerned, the one in which it was charged that we had conspired to effect insubordination or mutiny in the armed and naval forces of the United States. He denied the motion as to the second count, by which we were charged with conspiring to obstruct enlistment or recruiting. The case thereupon went to the jury.

The indictment had in fact, in the second count as well as in the first, charged us with publishing and selling a magazine, to wit, the Masses; specifically, the August, September and October issues thereof. No facts were alleged which would, if true, prove that this publication was the result of any agreement between the defendants made with the object of violating the law. It was, however, presumed that the prosecution had some such facts to introduce as evidence. This Mr. Barnes promised, in his opening speech to the jury, would be done. And thereupon the prosecution presented its case.

The Case Against The Masses

Eleven witnesses were put on the stand. (1) A clerk from the county clerk’s office produced a certificate of incorporation showing that there was in fact such a corporation as the Masses Publishing Company. (2) A printer testified that the August, September and October issues of the magazine had actually been printed. (3) Dorothy Day, formerly assistant managing editor of the magazine, testified that certain articles and pictures had to the best of her knowledge actually been written and drawn by the persons whose names were signed to them. Excerpts from these issues were read, and pictures were shown to the jury. Some of these articles and pictures expressed disapproval of war in itself, and other criticized certain government policies. One of the excerpts was a paragraph in which the hope of a fair trial was bespoke for Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, who had just been arrested; and another was a poem by Miss Josephine Bell which contained the statement: “Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman are in prison.” (4) A government official testified to the fact that Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman actually had been arrested and taken to prison. (5) A salesman testified that during the previous summer he had tried to sell Merrill Rogers something or other, and failed to do so, and that then the said Merrill Rogers had made a remark about the government’s military and naval program which he interpreted as disloyal; though upon cross-examination it appeared, from the context that this remark, if made, might have had a different and quite harmless meaning. (6) Another printer testified as to the number of magazines printed. (7) A bookbinder testified that he had delivered copies of the magazine to the Postoffice. Copies of the magazine published before the passage of the Espionage Law were then introduced as evidence, over the protest of the attorneys for the defense, and passages expressing disapproval of the system of conscription then being proposed, were read to the jury, together with other passages advocating the rights of conscientious objectors. (8) A government clerk testified to the fact that, subsequently to the remarks in the magazine about the prospective trial of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, they were indeed tried and not only tried but convicted. (9) A stenographer in the employ of the magazine, identified certain letters which had been dictated to her; these letters being exclusively concerned with sales of the magazine to newsdealers and subscribers. (10) A clerk in the employ of the magazine testified that when subscriptions were received the names of subscribers were put on the list, and that orders for particular issues of the magazine were turned over to the office-boy. (11) The office-boy testified that when he was given an order for a particular issue of the magazine, he thereupon filled the order, if the said issue of the magazine was in stock.

Then the prosecution, having offered evidence to show that the Masses magazine was actually written, edited, printed and maned, and that Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman had been arrested and subsequently tried and convicted, rested its case.

Mr. Hillquit then moved to dismiss the indictment against all the defendants, and that the jury be directed to bring in a verdict of not guilty, on the ground that no proof had been adduced of any conspiracy between the defendants. The judge denied the motion, except as to the defendant Josephine Bell-whose alleged co-conspiratorial relation to people she had never seen perhaps seemed humorous to the judge-and she was thereupon dismissed. It was pointed out that no evidence had been offered to show that the other defendants had met, agreed upon anything, or had any relation to each other aside from being owners of a magazine in which their work was published. The judge said that he thought that the fact of the defendants being associated with the same magazine constituted “prima facie evidence” of conspiracy. Whether or not it was conclusive evidence, he would permit the jury to determine. And he so ruled.

Mr. Hillquit and Mr. Malone then addressed the jury, opening the case on behalf of the defendants. They pointed out that the acts described in the indictment as “overt acts,” namely the publishing of the August, September and October issues of the magazine, were openly admitted by the defendants, but that no evidence had been adduced to show that there was any agreement of any kind to publish the particular articles and cartoons in question, and that there was no evidence to show that these articles and cartoons were intended to cause obstruction of recruiting or enlistment. They promised to show by the testimony of the defendants and others that the articles and pictures in question were not planned or agreed upon in advance by any meeting or conference of editors, and that no such conference was held, but that each editor sent in what he wished without previous arrangement with any other editor, and it was printed. They promised to show, moreover, by the testimony of the defendants, that their intentions in writing and drawing the articles and pictures for which they were individually responsible were legitimate and proper, constituting in every case a lawful exercise of the right of free expression of opinion.

Max Eastman on the Stand

The first witness for the defense was Max Eastman, editor of the Masses. He explained the origin and character of the magazine, as the product of a group of artists and writers with different ideas, who wished to own their own magazine and write and draw and publish in it whatever they pleased; the only policy of the magazine being complete freedom of expression for its editors. He read the articles written by himself which were specified in the indictment, and explained his attitude toward the war and American foreign policy. He showed that the editorials for which he was indicted, urged (a) that our government state its war-aims in conformity with the Russian policy of “no annexations, no indemnities, and self-determination for all peoples”; and (b) that proper provision be made for genuine conscientious objectors. He pointed out that both the things he had urged were subsequently done by the President, in his reply to the Pope, in his recent messages to Congress, and in his recent order concerning conscientious objectors. Max Eastman’s testimony, which lasted for the greater part of three days, covered a wide range of political and social thought, and made decisive the impression that in its essential aspect the Masses case is a struggle over the right of free speech and a free press in America. He told of interviews with the postal authorities, and with the President, and of the Masses’ injunction suit against the Postoffice Department, all undertaken with an intention of determining the rights of minority opinion to free expression within the law in time of war.

It was brought out as not the least ironic aspect of the trial that it involves an attempt to punish men who are now in accord with certain government policies, because they were a part of that intelligent minority whose vigorous agitation was instrumental in securing the adoption of such policies. And we wondered…we wondered if those in power who are desirous of securing “national unity” suppose that it is a good thing, now that such unity can honestly be achieved, to permit the reopening of an old quarrel, permit the loyalty of good citizens who were aligned against them on the vanished issues of a year ago to be now suspected and insulted?

Max Eastman said what was in all our hearts when, during the course of an utterly candid statement of those year-old views in cross-examination, he was questioned about an article in which he had expressed a distaste for the “ritual of patriotism.” Our minds went back across the gulf of months to the time when the American flag and the national anthem were being used for personal and partisan purposes by reactionaries, jingoes, militarists and hysterics, and most offensively of all perhaps by Mayor Mitchel in his ill-advised attempt to convince the people of New York City that it would he treason to vote for anybody but himself for mayor…Mr. Barnes’ question cut across our thoughts. “Will you tell us,” he was asking, “if the sentiments therein expressed, which I have just read to you, are your sentiments today?”

A. “No, they are not, Mr. Barnes. My sentiments have changed a good deal. I think that when the boys begin to go over to Europe, and fight to the strains of that anthem, you feel very different about it. You noticed when it was played out there in the street the other day, I did stand up. Will you let me tell you exactly how I felt?”

Q. “Go ahead.”

A. “I felt very sad; I felt very solemn, very sorrowful, because I thought of those boys over there dying by the thousands, perhaps destined to die by millions, with courage and even laughter on their lips, because they are dying for liberty. And I thought how terrible a thing it is that while they are dying over there, while the country is gradually coming to a feeling of the solemnity and seriousness of that thing, the Department of Justice should be compelling men of your distinguished ability, and others like you, all over the country, to waste their time, persecuting upright American citizens, when they might be hunting up the spies of the enemy, and the profiteers and friends of Prussianism in this country, and prosecuting them. That was my thought while the hymn was being played.”

Merrill Rogers was the next witness. He testified to his duties as business manager of the magazine, and identified letters and circulars written by himself with the object of increasing the sale of the magazine, and other letters expressing opinions unfavorable to conscription, written before the passage of the Espionage Act. He absolutely denied ever making any such remark as that attributed to him by the disappointed salesman. And he told of having gone to Washington, long before the passage of the Espionage Act, to consult George Creel, the “Censor,” as to the legality of a certain advertisement in an issue then in press. Mr. Creel, he said, had informed him that there was nothing unlawful in the advertisement, nor, so far as he had examined it, in the magazine.

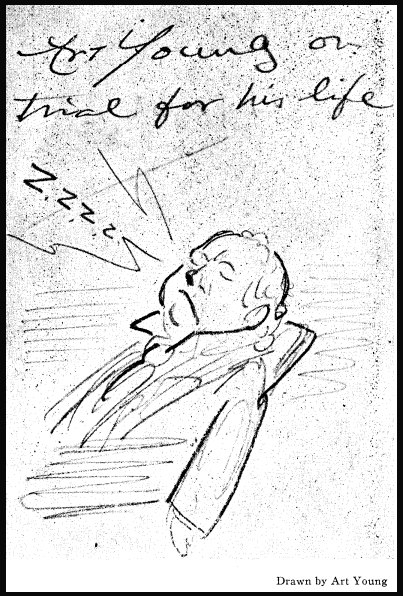

Why Is An Artist-By Art Young

Art Young was then put on the stand. Art had been busy throughout the trial drawing pictures of the judge, the jury, the lawyers, the witnesses, the court attendants. He was quite happy so long as he had a pencil in his hand, and he had probably forgotten that he was on trial for something resembling treason, and facing the possibility of twenty years in prison. He radiated an ineffable good-nature which made it impossible to regard him as anything so malignant as a conspirator. He testified as to how the magazine was run, and in a somewhat bewildered way as to his “intent” in drawing the cartoons for which he had been indicted. He thought their meaning was perfectly clear. They spoke for themselves, he said. “What did you intend to do when you drew this picture, Mr. Young?” Intend to do? Why; to draw a picture-to make people laugh-to make them think-to express his feelings. For what purpose? For the public good. How did he think they would effect such a purpose? Art scratched his head. He did not think it was fair to ask an artist to go into metaphysics. Had he intended to obstruct recruiting or enlistment by such pictures? No, he hadn’t been thinking of recruiting or enlistment at all! He couldn’t see what possible connection those pictures had with obstruction of recruiting or enlistment. He mentioned a little. picture of Mr. Barnes which the jury had seen; and he suggested that maybe someone would think that he had drawn that picture to discourage Mr. Barnes from enlisting!

The ordeal over, Art Young went back to his seat, and fell into an exhausted slumber. Dudley Field Malone whispered hastily to one of the other defendants, “For heaven’s sake, wake Art Young up, and give him a pencil! Tell him to try to stay awake until he gets to jail!” So Art, refreshed by his nap, drew a picture of himself snoring in the court-room.

Now, we just ask you, where is the satisfaction in trying to convict a man who behaves like that-a man who sleeps like a babe in the court-room where he is waiting to learn whether or not he is guilty, and if he will have to spend the rest of his life in prison!

How It Felt to Be a Witness

“Floyd Dell will take the stand.” I did. And, since I am engaged in ‘telling how it feels to be tried, I may as well confess that I took it with, pleasure. I had always secretly felt that my opinions were of a certain importance. It appeared that the government agreed with me. And a government does not do things by halves: it had provided a spacious room, and a special and carefully selected audience of twelve men, who were under sworn obligation to sit and listen to me. Under such circumstances it was naturally a pleasure, to tell the government what I thought about war, militarism, conscientious objectors and other related subjects.

Moreover, I found in cross-examination the distinct amusement of a primitive sort of game of wits. Mr. Barnes, under the guise of repeating some statement you have made, asks you to agree to some statement of his own, in which, hidden away as carefully as may be, is a verbal trap which he intends to spring on you. “I understand you to say–.” Of course Mr. Barnes does not understand you to say anything of the sort. But he certainly does hope that you will assent to his interpretation. Only, if you have an ear for words and a ready sense of their exact meaning, you politely decline to assent. “No, Mr. Barnes–” and you repeat what you actually did say.

The method of conducting a discussion in a court-room is faintly suggestive of a Socratic dialogue. And, though your questioner stands thirty feet away, and you are adjured to “speak up so the jury can hear,” you lose all sense of any presence except that of your friendly or inimical interlocutor. You are surprised when, at some interruption from outside that magic circle of question and answer, you discover yourself in a court-room full of people. It is a strange, stimulating and-or so at least I found it-an agreeable experience.

Mr. Barnes had read the previous day from a mysterious document which he refused to introduce in evidence, but which appeared to refer to the proceedings of a meeting of editors of the magazine away back in 1916. It was in fact a translation of some stenographic notes of that meeting, which were now produced, and verified by the stenographer. These notes recorded the heated language used on the occasion of the annual “row” between two factions among the editors over artistic questions. They were used by Mr. Barnes in an attempt to prove-heaven knows exactly what, probably that the alleged conspiracy had been initiated on that date. To substantiate his vague theory, he called to the stand Dolly Sloan, the wife of John Sloan, who had figured prominently in that epic and almost forgotten battle of long-ago. Her pungent testimony, however, confirmed absolutely the explanations previously made by the defense, and knocked Mr. Barnes’ romantic surmises into a cocked hat.

Three more witnesses concluded the defendants’ case. Inez Haynes Irwin, a former contributing editor of the Masses, Howard Brubaker of Colliers Weekly a contributing editor of the Masses, and Louis Untermeyer, a contributing editor, testified to their diverse views with regard to the war, and their continual relationship to the magazine.

Then, on Thursday of the second week, the ninth day of the trial, the attorneys for the defense summed up the case to the jury. The evidence was all in, every act, every word, every letter of the defendants had been scrutinized, the whole history of their magazine and the course of their individual opinions on almost every conceivable political topic had been set forth. They had published a radical magazine in which unpopular views were expressed. So much was proved. The question was, did the defendants conspire to violate the Espionage Law, or were they merely exercising their lawful right to the free expression of opinion? The jury must presently decide.

[Drawing rearranged: drawing of Floyd Dell placed at beginning of article.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-June 1918

Page 7: “The Story of the [First Masses] Trial” by Floyd Dell

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1918/04/v1n04-jun-1918-liberator.pdf

See also:

Scroll down to links for info on The Masses and The Liberator:

Hellraisers Journal, Tuesday June 4, 1918

New York, New York – Retrial of Masses Editors Expect

From The Liberator: A Word from The Masses Defense Committee Regarding Recent Trial

Hellraisers Journal, Friday May 3, 1918

New York, New York – John Reed Facing Federal Charges

John Reed Returns to USA to Face Federal Charges of Conspiracy to Obstruct the Draft Law

Scroll down for examples of works by Eastman, Dell, Reed, Bell, Glintenkamp and Young which led to the charges:

Hellrasiers Journal, Tuesday November 20, 1917

New York, New York – The Masses & Staff Indicted by Federal Grand Jury

Max Eastman, John Reed, Art Young & Four Others from The Masses Indicted by Federal Grand Jury

Nov 19, 1917, Indictment

United States of America v. The Masses Publishing Company, Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, C. Merril Rogers Jr., Henry J. Glinterkamp, Arthur Young, John Reed, and Josephine Bell

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7595374

Max Eastman

http://spartacus-educational.com/Jeastman.htm

Floyd Dell

http://spartacus-educational.com/ARTdell.htm

Defending the Masses:

A Progressive Lawyer’s Battles for Free Speech

-by Eric B. Easton

University of Wisconsin Pres, Jan 9, 2018

(search: “merrill rogers” -and other defendants)

https://books.google.com/books?id=5kU_DwAAQBAJ

Art Young

http://spartacus-educational.com/ARTyoung.htm

“A Tribute” by Josephine Bell

https://www.marxists.org/subject/women/poetry/tribute.html

Henry J Glintenkamp

http://spartacus-educational.com/ARTglintenkamp.htm

Dudley Field Malone

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dudley_Field_Malone

Inez Haynes Irwin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inez_Haynes_Irwin

Howard Brubaker

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Brubaker

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~