———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday April 6, 1909

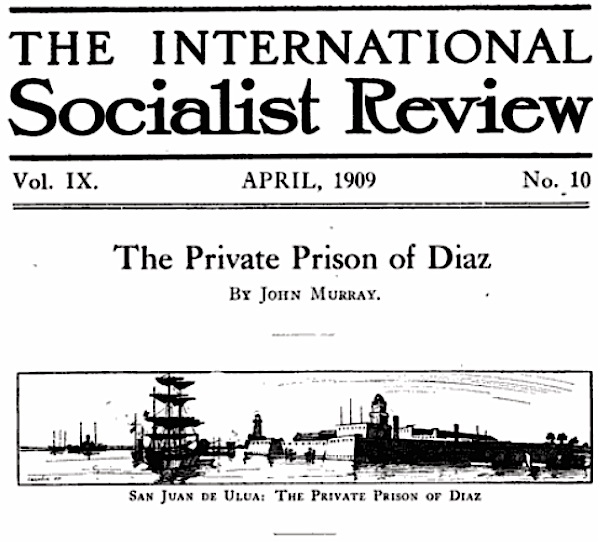

John Murray on the Horrors of the Private Prisons of Diaz, Part III

From the International Socialist Review of April 1909:

[Part III, Conclusion]

[John Murray’s interview with the escaped prisoner, Antonio, continues:]

The sick man’s pauses in this narrative were frequent. At times the old lady give him water to drink, and then again he would take two puffs at a cigarette rolled by the president, all of which kept him going to the end of his story.

We were accused of participating in the rebellion started in September, 1906, by the Junta Revolucionaria Mexicana in Jimenez, and in Acayucan. Chained in gangs with two hundred others, we were brought to the fortress and political prison of San Juan de Ulua.

Some of us were betrayed by that Judas, Captain Adolfo Jimenez Castro, an officer of the post at Cuidad Juarez, while others were betrayed by Trinidad Vasquez at Cananea.

Among the number were persons entirely innocent of any participation in the rebellion, but they received neither consideration nor mercy, and, like many of us, saw their homes burnt by the soldiery and their families left to starve.

With whips they drove us south.

From the pier at Vera Cruz, we were loaded into a sailboat and taken to the island, and after having our names written in the prison records, we were turned over to a keeper notorious for his brutality. This man’s nickname was certainly a strange one. The prisoners called him “Madre Ingrata,” “Ingrate Mother,”—a terrible nick-name, but it fitted him. With the squat, ugly body of a toad and the brute strength of a gorilla, a yellow, oily skin, big, bullet-shaped head and short neck, small eyes and big cheek bones, this “Ingrate Mother” was of the type best suited to the murderous purposes of the prison. Always in his hand could be seen a club—and usually it was striking this way and that among the prisoners.

He commanded us to march into the yard, and while we stood there together, he separated Juan Sarabia and Canales from the rest of us and with vile words pushed them before him into one of the dungeons, ordering them to strip off their clothes. Returning, he treated us all in the same manner and for hours we were left thus, naked. It must have been late in the afternoon when the trusties came back with the regulation prison clothes, ragged and vile from the back of former prisoners, dead or discharged.

Sarabia was in one of the dungeons and to him went the “Ingrate Mother.” Swinging back the iron bars he roared in a great voice:

“Out with you!”

The naked boy moved quickly.

Down upon the stone flags the evil-eyed brute flung a little bundle of rags, foul with dirt and vermin. Pointing to them with the handle of his whip, he gave the command, menacingly:

“On with them!”

So loathesome was this heap of clothing that for a moment Sarabia hesitated, and for this swift punishment overtook him. Down on the bare shoulders of the delicate prisoner came the whip again and again, until blood ran red on his back. Sarabia stood through it all without a protest, intensely pale, and then staggering back as if drunk came to our dungeon, the “Ingrate Mother” following him with the whip still going like a flail.

The whippings fell on us all. Cesar Canales, another political, was called one day by the trusties to the door and with the excuse that he did not move quickly enough, they fell upon him and beat him for more than ten minutes.

Antonio Balboa, another comrade of ours, was lashed by the trusties until he could no longer stand. And so it happened to all of us one after another.

In darkness, chilled with the dampness that moistened our garments and penetrated our bodies, we struggled day after day to breathe the foul dungeon air that had never been purified by a ray of sunshine. From open barrels in our cells, in which were held the excrement of many weeks, came the most pestilent emanations. Decaying meat, mouldy bread, and impure water we were forced to swallow by the pangs of hunger. The only hope left to us was the hope of death.

Fifty of our companions succumbed and their dead bodies were carried out by the prison trusties. Many of these poor people were entirely innocent of the charges placed against them, being neither revolutionists nor criminals.

Many others became insane—and were beaten the worse for it. God grant that I may forget those sights!

The fortress of San Juan de Ulua is on a block of an island facing Vera Cruz. The prison cells occupy the outer or sea side. Those above the sea level are for the non-political prisoners, but the dungeons below the water are for the political enemies of Diaz.

Thirty feet wide and forty-five feet long are about the dimensions of these larger dungeons, whose thick walls are continually dripping with water seeping through from the sea. Within there are eight hundred men living like vermin.

In the first days of our confinement we were happy in being allowed to live among these prisoners, but as the comandante feared that we might make political propaganda among them, we were put in separate dungeons below sea level. So we lived for one terrible year. Dirt, vermin, decayed food and foul air, the continuous drip of sea water through the walls, brought on sickness. The prison physician prescribed purgatives and diet. We tried to write to our families, but the letters were destroyed by the trusties.

Only eight of our comrades were actually sentenced. The others were held without trial. A special judge, Amilio Bulle Gore, was appointed to try our cases, but all that he did was to open our letters and hold the money that was sent to us by friends.

The dungeons in which we were confined were separated by iron bars, and called, the first, “Hall of Reflection,” the second, “Gloria,” and the third, “Inferno.” In the first was Cesar Canales, with about twenty of our comrades from Chihuahua and Sonora. In the second, eight of the revolutionists from Vera Cruz city, and in the third, Roman Martin with the revolutionists from Coatzacoalcos, State of Vera Cruz.

The first dungeon was twenty-eight feet wide and thirty-six long, the second, seven and one-half feet wide and fifteen long, and the third, four and one-half feet wide and nine feet long—all of them being only five and one-half feet high.

So dark are these dungeons that it is only possible to see with artificial light, while the prison smell is made worse by the filth and mud upon the floor. Thousands of parasites, common to hot, damp lands, ran over us.

Three small ventilators kept us from quick asphyxiation and in every one of these holes were the vile barrels of excrement, only carried away once a week, and therefore overflowing upon the floors and causing the condition of our living place to be horrible beyond description.

In the first year of our incarceration we did not once see the sun shine, even though the prison doctor ordered us to be allowed fresh air.

Since December of last year we were kept “incommunicado” and were prohibited from sending any letters or receiving any from our families.

In the month of May of this year we were given the privilege of going to an adjoining dungeon into which the sea oozed freely and bathing ourselves. Although there was a horrible deposit of mud and filth in this place, yet we considered such a bath a great boon. After our baths we had to scrape the mud from our bodies.

Juan Sarabia was not kept in the holes of the “Reflection,” “Gloria,” or “Inferno.” These places have openings which permit the prisoners to talk to each other. “Juanito” was put into a dungeon known to the prison as the “Purgatoria,” which is only large enough for one person, but not long enough to permit the inmate to straighten himself out when lying down.

In “Purgatoria” it is absolutely dark. The poor boy has not seen the smallest ray of daylight since December—and water covers half of the stone floor! The jailors did not allow him to talk to them. In silence, darkness, and inaction, he is dying of tuberculosis—our “Juanito.”

The president beckoned to the old woman as the speaker stopped exhausted panting, and the pillows were lowered beneath the sick man’s head.

With noiseless steps we left the room and went down to the waiting men below. The group meeting was breaking up as we re-entered the room. The president held up his hand for silence and attention:

What message shall we send to Magon by our American friend?

The secretary answered for them all, speaking for the first time in English:

Two things you must tell Ricardo when you return: First, that Vera Cruz, never forgets the massacre of her citizens ordered by the butcher Diaz in 1879, and, second, that the jungle is ready to rise.

But the fierce intensity of the black-browed Vera Cruz revolutionist could not be expressed in cold English and he almost immediately dropped back into Spanish, explaining the situation in the south with these dramatic phrases:

Senor, the swish of the machete is the dominant sound of tropical Mexico. No one can enter the jungle without the aid of the long knife, and so, every one of our field-hands in the South is armed.

Banana groves shade the young coffee bushes, and an endless variety of fruits are to be had for the plucking—and so every one of our workingmen in revolt can be fed.

The jungle is a hiding place for the pursued, impenetrable to an invading army—and so every wage worker in Southern Mexico has a last refuge.

Think of these things and then remember how Cuba, another land of the machete, the banana, and the jungle, successfully fostered a revolution.

“But have you the guns?” This question I asked of every group in Mexico, for upon it seemed to my mind to hang the fate of the revolution.

“Some we have and more are coming. You must remember, senor, that the same waters of the Gulf of Mexico that brought arms to Cuba flow to the shores of Vera Cruz.”

And why not? Why should Cuba have fought successfully for liberty and Mexico be held in slavery? These thoughts were forced upon me as I stood looking into the fiercely sparkling eyes of the speaker.

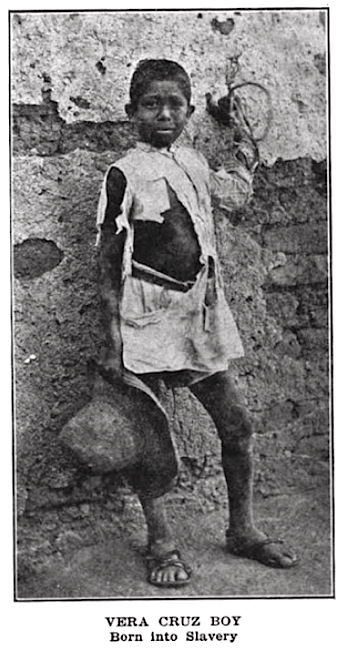

I bade goodby to the revolutionists of Vera Cruz, and on the following morning traveled inland to the Valle Nacional, whose rich tobacco fields are tilled by slaves of the Mexican Republic.

———-

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Freedom Ricardo Flores Magon, Speech re Prisoners of Texas, May 31, 1914

https://isreview.org/issue/101/intervention-and-prisoners-texas

https://books.google.com/books?id=JHOd18yUxrAC

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1908-June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

ISR – Apr 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA736

“The Prisons of Diaz” by John Murray

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA737

“The sick man’s pause in this narrative were frequent.”

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA737&pg=GBS.PA747

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From the International Socialist Review:

John Murray on the Horrors of the Private Prisons of Diaz, Part I

John Murray on the Horrors of the Private Prisons of Diaz, Part II

Re Veracruz Massacre of 1879, see:

Barbarous Mexico

by John Kenneth Turner

C. H. Kerr, 1910

https://books.google.com/books?id=7mdKAAAAYAAJ

Chapter IX: The Crushing of Opposition Parties

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=7mdKAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA160

Re June 1879

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=7mdKAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA164

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Las Soldaderas – Revolución Mexicana