You have to act as if it were possible

to radically transform the world.

And you have to do it all the time.

-Angela Davis

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday November 5, 1918

“An army of women is entering [all] branches of industry.”

From The Crisis of November 1918:

THE COLORED WOMAN IN INDUSTRY

Mary E. Jackson

JUST as colored men are going into the Army, so colored women are being recruited into industry. Thousands and thousands of eager boys have gone to France; we all know about them. Few of us realize that at the same time an army of women is entering mills, factories and all other branches of industry.

I undertook an industrial survey of these women for the National Board of the Young Women’s Christian Association. I investigated the increasing numbers employed, the kinds of work, wages, working conditions, what has been done, and what more can be done to raise the efficiency of the workers. At the same time I began in each city the organization of industrial women into clubs.

A great alteration has come in manufacturing sections like Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cleveland, St. Louis, Louisville, Detroit and Chicago. The shifting of so many thousands of Negro laborers and their families from the South during the past two years, has brought a large supply of women’s labor into these districts, where it is much needed. The matter is well summed up in a letter from Rachel S. Gallagher, Director of the City Free Labor Exchange, Cleveland, Ohio, written in the spring:

If you had asked me two years ago about the colored girls as wage earners, in Cleveland, I would have told you that they could be found in housework, as laundresses and cleaning women, as maids, in a few cases in banks and offices, and there were a few employed by a cigar box manufacturing concern.

Today, however, when I started to list the firms where they were employed, I found that they had entered nearly every field of women’s work, and some work where women had not previously been employed. To be sure, at times in small numbers, but they have made an entrance.

We find them on power sewing machines, making caps, waists, bags and mops; we find them doing pressing and various hand operations in these same shops. They are employed in knitting factories as winders, in a number of laundries on mangles of every type, and in sorting and marking. They are in paper box factories doing both hand and machine work, in button factories on the button machines, in packing houses packing meat, in railroad yards wiping and cleaning engines, and doing sorting in rail road shops. They are found in cigar factories stripping and packing, and in an electrical supply manufacturing plant doing- hard work. One of our workers recently found two colored girls on a knotting machine in a bed spring factory, putting the knots in the wire springs.

In Louisville, probably between two and three thousand, women are employed in laundries, preserving companies and factories, manufacturing overalls, feathers, wool, chairs and tobacco. It is in the tobacco factory that Louisville finds its acute industrial conditions.

Sometimes large numbers of women are employed and sometimes only a few. For instance, in Kansas City, 542 women are employed in packing plants. In St. Louis, nut factories have about 2,000, while two bag factories employ about 120. In most places they come in slowly. In Philadelphia, a pantaloon factory has two girls pulling bastings, a petticoat factory numbers three colored women out of twenty women; a dress factory, two out of twelve; a waist maker, five out of fifty; a hosiery mill, five out of thirty-two. Whether they enter in large numbers or singly, it is sure that they are in industry to stay, and their working conditions have become of vital importance, not only to them but to the nation at large.

The Ohio letter mentions only a few of the lines of work in which we find women newly employed. They are in both the skilled and unskilled trades. This comes out clearly in a report from Pittsburgh, where two different factories are especially mentioned. A garment factory making raincoats for the Government has had about twenty girls. They are careful to employ the better educated type of girl, but they work on a separate floor and do not mingle with the white girls who are prejudiced against them. Wages and conditions, however, are exactly the same for both. The work is machine sewing and sticking with glue.

The other company, which uses untrained labor, has employed colored girls for three years. About fifty of the seventy-five girls they employ are colored. The other girls ar foreign, evidently low grade labor. The work is picking and sorting rags, papers bottles, etc. Wages and conditions are the same for both races. They work together and apparently there is no antagonism on either side.

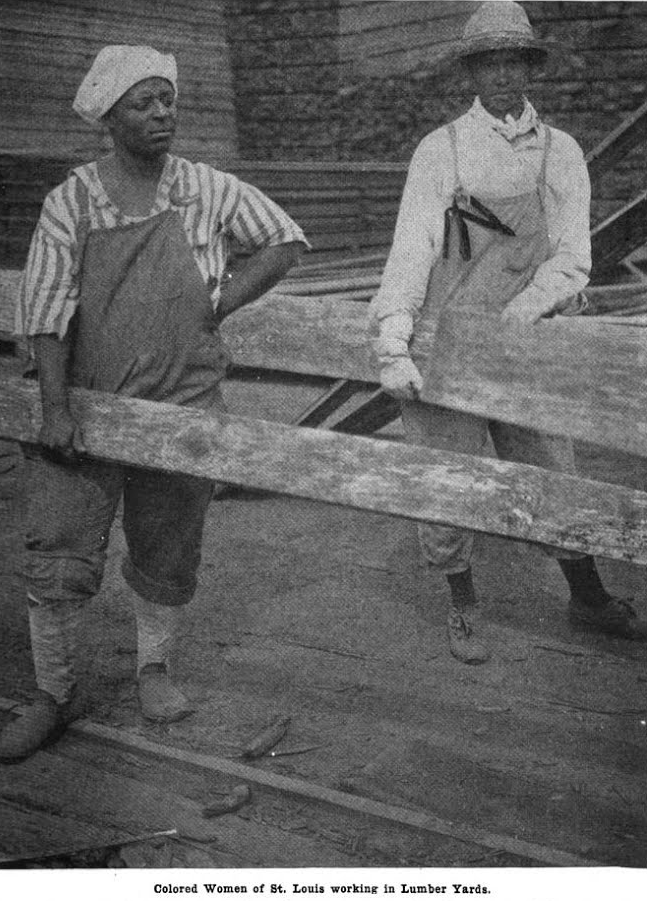

The change brought about by war conditions is in many cases spectacular. Women are working in the tobacco fields in Connecticut; Indiana reports them in glass works; in Ohio, they are found on the night shifts of glass works; cotton chopping and harvesting claim them in Texas; they have gone into the pottery works in Virginia; wood-working plants and lumber yards have called for their help in Tennessee, while in St. Louis, where the special investigation has been carried further than in the other places, they dip tile in roofing plants, shovel rock into wagons in clay yards, truck brick and load scrap iron; on railroads they are utilized as section hands and engine wipers. So great a change as this deserves close attention in the matter of wages and of working conditions.

Wages among women are unstandardized. There are several reasons for this: In the first place, the labor of colored women is almost entirely unorganized. The attitude of the unions toward them is evasive. Of the six labor secretaries with whom I talked last December, in New York City, only one set up any objection to colored members. The others agreed that the colored woman was not only welcome to the unions but that she must be made to see the mutual advantage of her joining. But the fact remains that there is practically no colored membership. In the 30,000 members of the Ladies’ Waist and Dressmakers, only about one hundred are colored, although the needle trades stand first among those which the colored women are now entering so rapidly.

A significant and encouraging incident, however, was reported from Philadelphia, in the early summer. A strike was called by this union in an establishment where colored girls were being paid one cent, for which white girls had been paid three cents. The colored girls promptly joined the strike and the union and the pay was raised.

Again, at this period much of the colored labor is unskilled, and unskilled labor is helpless in the matter of wages unless organized. Then, too, in many of the industries the women are beginners and, therefore, unable to deal with the situation intelligently. Added to this is the general assumption that women should be grateful to be paid anything at all and that their wages have no relation to their standard of living. Piled on top of all of these disadvantages is the fact that the women belong to the Negro race. Some people have actually said that the standards of Negro life are so much lower than those of the white that the colored woman does not need as high a rate of wage.

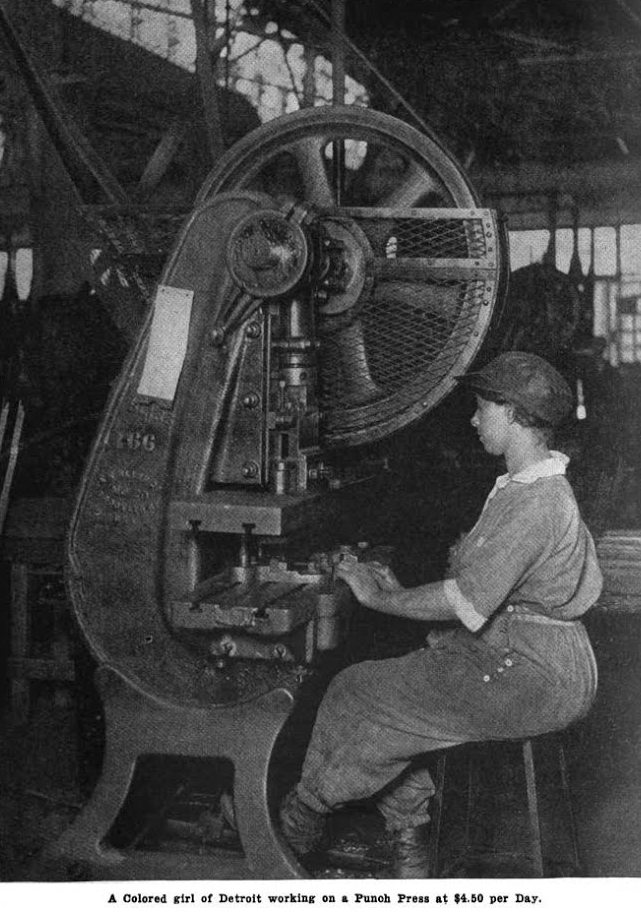

The most encouraging case that I have come across was in a Detroit factory, where we found one colored girl making as much as $4.50 a day working at a punch press. In startling contrast to this is the small amount paid for unskilled work. In nut-shelling factories, where the women pick out the meats after the shells have been cracked by machinery, a woman makes from $6.00 to $7.00 a week. She is paid ten cents a pound for whole meats and five cents a pound for broken meats. Although it is possible for a woman to make as much as $12.00 a week, this seldom happens.

In another big factory the women’s wage was until recently only $6.00 a week. When I was lecturing to a group of business women of that city, I mentioned the very low pay of this factory. By good fortune the welfare worker, a white woman, who has an equal interest in the welfare of the colored workers, was present. She took the matter up with the manager of the factory and the $1.00 a week raise was announced.

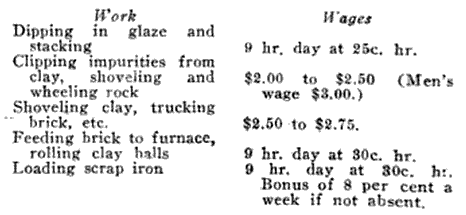

The pay for heavy unskilled work, formerly performed by men, is higher than the rate paid for what has been known as women’s work, although unusually lower than the amount which men received for the same work. The following figures illustrate this:

One must not rely upon the given rate because it is so nibbled away by absences, perhaps because of the unhealthy nature of the work, by fines, and various other methods. In many cases the workers themselves do not realize how much less they receive than the regular rate.

The serious part of this matter is that women are undercutting men in wages. This has the effect of lowering wages all over the country. Of course, women have always done this. Every possible precaution must be taken to avoid it. A protest has been sent in one state to the Director-General of Railroads, pointing out that women were being employed in freight yards and round-houses for twenty-two cents an hour, while men were paid thirty cents an hour for the same work.

The working conditions vary as much as the wages. When large numbers of colored girls are employed, they usually work in rooms separate from those of the white girls. When there are any hazards or disadvantages, it is the colored woman who is subjected to them. Conditions depend absolutely upon the attitude of the firm. Some old, well-established companies provide equally well for all women. One firm which I found in the West, under the guidance of an expert welfare worker, has provided for white and colored women alike: lunch rooms, shower baths, a circulating library and dressing rooms with steel lockers.

The tobacco factories all through the South have very bad conditions. I was once shown a coat room as if it were a remarkable concession on the part of the management. As a rule the women sit at their work stripping the tobacco while they eat their luncheon to eke out their meagre pay. The same factory which raised the wages, although it has at present most unhygienic conditions, is about to put up a new building in which the colored women are to have the same good accommodations that are provided for the white workers.

A letter from a small Kansas City [employer?] presents a situation which must be occurring in many places:

We have about fifteen colored girls working at our Santa Fe Railroad Round-House wiping engines. The hours are from seven until five and the wages two dollars and forty-seven and a half cents a day. These are the only women working in the shops. They are forced to walk almost two miles in their greasy overalls to their rooming places as a colored person cannot rent a house near the shops. Their own people are too poor to board them so they are forced to prepare their, own meal when they get home, wash their clothes and prepare their lunch for the morrow.

We plan, if possible, to rent a small house in that vicinity where the girls may change their clothes and rest.

All working conditions have a direct bearing upon the amount of work turned out for instance, I noticed one day on the street car a colored girl whose stained hands indicated that she was working in dye. She told me that fifty girls were taking men’s places dyeing furs. They lifted the pelts from the hot vats and hung them up. During the hot weather this work was almost intolerable. The employer had promised $10.00 a week, but he did not give it. He soon shifted the newcomer on to piece work. If she stayed long enough, she might be able to make from $15.00 to $18.00 a week; but no one could stand it longer than one or two weeks. The result was a huge labor turnover. Of course, the bad conditions were responsible for this, but the employer said it was because colored labor was unstable.

The altering of the bad phases of employment depends in the end upon the progress of education. We must educate the public, the employers and the girls themselves. It is especially important that leaders among colored people—like ministers, club leaders, teachers, social workers—thoroughly inform themselves on this matter, which is of more than momentary importance. Last summer the Young Women’s Christian Association had this far-reaching vision, realizing that such work was both a war measure and a preparation for after the war. Now is an especially good time to present the matter to the general public in the proper light, because it is now to the national advantage to give the Negro a square deal.

Employers must be won to employ colored girls. Sometimes we are able to obtain from a Chamber of Commerce a list of manufacturers who might be willing to take on colored help. The accomplishment of one worker shows how much can be accomplished by patience, ability, tact and persistence. She opened fifteen factories, including cigar factories, packing and novelty companies, clothing companies, knitting mills, trunk factories, a foundry, a toy factory, an undergarment manufactory and a fur factory, and placed 346 women in them.

Individual girls can accomplish much if they go about it the right way. A girl walked into a wholesale drug company in a southern city and asked for work. She was taken on as an experiment. A few days later she brought six friends with her. They all made good. By the time the Y. W. C. A. investigator got around to that store, twenty were working there and the superintendent promised to take thirty-five more to fill capsules and label bottles. The best of all was that he bore witness to the girls’ good work by saying:

“Show the colored girl what you want done, and she does it quicker and better than the white girl.”

All this effort, of course, is of no value unless the girls give satisfaction. We must educate them both to individual effort and to group effort. Girls come to me constantly for interviews about their industrial future. It is natural that they should become discouraged. When a girl has been refused positions time and again, she may not have the persistence to apply at the very time that she would be accepted. We found, for in stance, a graduate of a normal school mending bags at $6.00 a week. She needed our encouragement and assistance to get into a position in which she could use her ability.

In one city we found in three office buildings twenty-six high school girls who were answering telephones and dusting, at an average wage of $5.00 a week without any hope of further advancement. Girls like these must be encouraged to further effort. The one greatest barrier of all lies in their own minds. Before outside obstacles may be overcome, we must convince the girl of the possibility of success.

The group education is equally important. The colored girl has never before been held responsible to other girls and to the community. She is now in a new relation toward her country. She must come to see that she is no longer “different;” she must learn to look upon herself as a part of a unit. The future of all girls rests partly upon the accomplishment of the individual girl.

The supervision of colored factory girls by colored forewomen is of the utmost importance. The girls are more efficient and have more interest in their work because the forewoman herself is interested in what they accomplish. I found this strikingly illustrated in one factory where one room full of girls was under the charge of a white forewoman while the second was under the charge of a colored woman. In the first room, a happy-go-lucky atmosphere prevailed; in the second room, the girls were quiet and industrious. The forewoman had pride in her room. She set a certain standard for girls to live up to.

The Young Women’s Christian Association is organizing clubs among the workers of all factories as rapidly as possible. These clubs offer constructive, continuous recreation which is linked up to the community needs. Organization is, after all, the solution of industrial problems, and every possible method of achieving it must be utilized.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMGAES

The Crisis, Volumes 15-18

(New York, New York)

-Nov 1917-Oct 1919

https://books.google.com/books?id=Y4ETAAAAYAAJ

The Crisis of Nov 1918

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Y4ETAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.RA2-PA1

“The Colored Woman in Industry”

-Mary E. Jackson

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Y4ETAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.RA2-PA12

See also:

Rosie’s Mom

Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War

-Carrie Brown

UPNE, 2002

https://books.google.com/books?id=DXzL2mEiG14C

Women and the American Labor Movement

-from World War I to the Present

-by Philip S Foner

Free Press, 1980

Note: beware when buying this book. There is Volume I, Volume II (this volume) and a compilation (much condensed) of the two volumes, which is what one ends up with if seller is not careful.

https://books.google.com/books?id=5kKBAAAAMAAJ

Can be borrowed online here: hopefully, this is actually Vol. 2:

https://archive.org/details/womenamericanla01fone

From Chapter I: The Industrial Scene in World War I:

[From the Seattle Union Record of November 2, 1918:]

Women are being employed in considerable numbers in the lumber mills at Potlach [Idaho], in this country, where lumbermen are engaged in getting out airplane stock. They wear overalls, do a man’s work and receive a man’s wages, according to the mill men…Employment of the women is declared to be due to shortage of help in preparing the white and yellow pine for airplane use.

[Ten Million American women:]

Almost 10 million American women were to enter gainful employment before the armistice. At least 3 million of them were in factories, over one million of these directly concerned with war equipment; 100,000 operated long-distance and intracity transport; 250,000 fabricated textiles (including items from tents to uniforms); and at least 10,000 were forging metal products. Further, female hands would play an essential role in providing sufficient food, clothing and housing to equip the four million men in service at domestic installations and on overseas battlefields.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~