—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday January 26, 1913

New York, New York – Theresa Malkiel Observes Ten Thousand Pickets

From The Coming Nation of January 25, 1913:

Striking for the Right to Live

-by Theresa Malkiel

[Part II of III]

Ten Thousand Pickets

A tumult, a commotion, a shout and I found myself eagerly peering out of the window; many heads pressed close about and in back of me. They were coming from the field work, the pickets I mean. Not two, not ten, not a hundred, but 10,000 strong, an army of labor, a city in itself.

My God! how powerful they looked. Every stone in the street pavements, every brick of the dark grim tenements seemed to have spoken to me of it. I was moved to tears of joy. I felt like a long-lost traveler who had at last found the right road. Now I knew it. There is where the true power, the road to freedom, was to be found in the combination and solidarity of labor.

These ten thousand tailor pickets were a power that even New York could not combat. It would take the entire police force to fight them man to man, or rather man to woman, for the women are really the greater fighters, the most determined pickets of the two.

Out of the picket line came an Italian woman, a mother of six children. She was beaten up by the police while watching her shop with a few others. The brutal thugs in police uniform knocked her about, bruised her face, disheveled her hair, tore her clothes off her back and Lord knows what else they might have done to her had she not been rescued by the army of 10,000.

Thus is the working class mother treated by our capitalist government, for no other crime than the earnest desire to earn an honest living for her children.

She took it calmly, stoically, as they all take it, the true Roman matrons that they are. “It’s all for my childs,” she said. “I fight them again. I no care.”

And still the picket line marched onward like a threatening cloud from above. They feared nothing, not even the elements. Occasionally one would fall out of their midst for the same reasons as the Italian woman came out of the picket line, but the men, like the women, took the medicine dealt out to them by the police and thugs like good fellows.

There was Sam Spilka, who got a needle stuck into his eyelid by a mean, low cur of a boss. His face was swollen, his eye all bandaged up. But Sam pointed smilingly at it, “it’s my badge of honor.”

“I wish I was young, I’d go with them, too,” said old Mr. Simkovitch following the passing lines. Mr. Simkovitch said he was “a presser by pants,” he got $6 a week in season, but he and his wife had to live on the money earned during the season the whole year round. Theirs wasn’t much of a life, he said, but his old woman agreed with him that the tailors had to go out on strike, for they were starving anyway. He and his old woman were ready to stick by the strikers as long as the fight would last.

The Fighting “Forward”

Going out of Clinton Hall I moved along with the picket lines toward Rutger’s Square, or the Forward’s Square as it may be more rightfully called. For the Jewish Daily Forward, with its new twelve-story building, is really the central point of gravitation for the entire East Side. Every inch of ground on the Square was taken up by men, women and children. All strained their eyes and ears trying to listen to Alexander Irvine who was speaking to them on behalf of the Socialist party. The fact that they understood but little English seemed not to matter. He was speaking in the name of the Socialist party and the Forward he was their friend.

It was hard work to wedge one’s way through to enter the Mecca of the strikers, the Forward building. Strikers to the right of me, strikers to the left of me, strikers all around me. Every room, every corner, every nook of the twelve-story building was filled with strikers, thousands of bodies, with what seemed to be but one great soul, one hope to win the fight.

I spoke to Chernenko, a big stalwart Russian, he ironed coats 14 hours daily in the season, and got $12 per week. His money, like the money of all the garment workers, had to last for the year.

Eight months’ earning for twelve months’ existence. He said he had starved enough in Russia; he left for he could not stand it any longer; he would not put up with the despotism of the Tzar, nor was he going to stand for that of his boss Shamansky. Mrs. Heinrich, a good-natured German housefrau said that vests, or the finishing of vests, paid by far less today than it did five years ago. She was getting older, there was no prospect of her ever leaving work until her dying day, and she’d better stay out with the rest and get better wages, shorter hours and work in a decent place.

“Brothers and sisters,” came the voice of the beloved leader, Max Pine, a good, red-blooded Socialist. “Our strike is the seed of a new life, the life of brotherhood and solidarity of labor.” His voice was drowned in a storm of applause.

“This is a new issue,” he continued. “We no longer fight single-handed. We are one body, one soul. This is an entirely new issue which confronts our bosses at present. They have brought us to it through their heartlessness and unmerciful greed, and now that the long hoped for miracle, the affiliation of the entire industry has happened let us be thankful to them.“

Discovering of Solidarity

Pushing and shoving and straining every muscle of my arms I managed to get out into the open once more and slowly work my way down the street to Canal and from there to the Bowery. All traffic was made almost impossible by the thousands of striking men and women most of whom were congregated in an area of twenty city blocks. Up the Bowery amidst the derelicts of the twentieth century I went to Beethoven Hall, where the 6,500 striking clothing cutters make their headquarters. There, like everywhere in the strikers’ headquarters, everything buzzed with life and animation.

“It goes without saying that we must stick together,” said Mr. Green, a presentable looking American gentleman who happens to ply the trade of clothing cutter.

“As a matter of fact, we all depend upon each other,” he acquainted me with the wonderful discovery, then added in a low voice:

“Would you believe it, it is getting as hard for me to make ends meet as it is for those poor devils of foreigners.”

The statement of one of the strikers is practically the statement of all. They are fighting for a chance in this world, for the right to live. They love their children even like we love ours and they want to be able to do what is right for them. “I see my children, or rather they see me only on Sunday. They are asleep when I go to work at half past six in the morning and are asleep when I come back from work at ten o’clock at night,” a custom pants maker told me.

Nine Dollars’a Week

The man was unusually pale, dark blue rings encircled his sunken eyes, his hands were thin, emaciated. I knew he would not live to see his children grown. He had two of them. What would happen to the little tots? The tailor had saved nothing for a dark day, how could he his wages averaged $9 per week, he could scarcely keep body and soul together on that sum in the city of New York.

And yet $9 is the average wage made by the male hand workers in trade. It must be remembered that the majority are married and have families to support What wonder that their struggle for existence had reached the limit?

In the mass rebellion of the 125,000 men and women each individual garment worker sees a possible chance for redress and finds an outlet for his accumulated wrath.

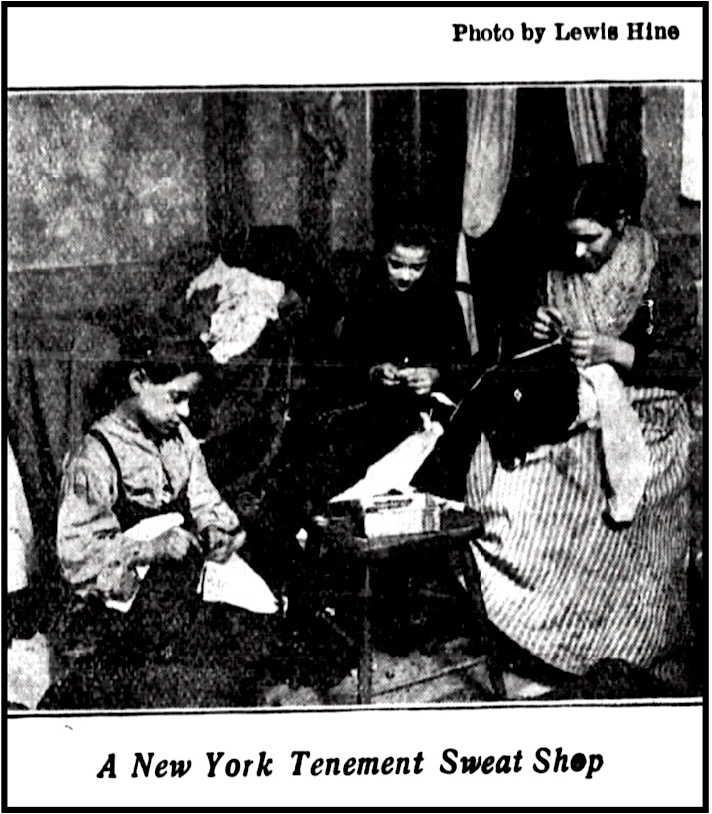

The tailor, though “his soul may have grown as thin as a needle,” wants to protect his children. He is tired of seeing them hungry most of the time, half naked, herded together like cattle in small, dark, dirty quarters, which capitalist society calls a home. His heart aches to see them die like so many flies. In the tenement district where most of the garment workers live, of every nine babies born, one dies before it is five years old.

The garment workers were driven to the present strike. The wages in the entire industry have not been raised for a number of years, although the making of the garments has become more complex. The tailor’s cost of living, like that of everybody else, has soared sky high. The tailors are a patient lot, their very work makes them so. They held out to the very last, but when the lines of exploitation were overdrawn, even the tailor’s limit of endurance came to an end. The bit was broken, the reins fell apart and like the proverbial mule, the garment worker balked. Not as an individual, not as a member of his certain trade, or his branch of the trade, but the whole industry, or to be more exact 85 per cent of it.

The Jews, Italians, Lithuanians, Germans, Russians, Letts and the few Americans, from the most skilled mechanics to the least trained button sewers all broke loose like a cloudburst on a summer’s day.

Like sheep in a field at the sight of a wolf they flocked together and for the first time in the history of the labor movement in the United States, made common cause.

Danger stared them all in the face, the instinct of self-preservation led them to co-operation. The cutters, who have heretofore been the aristocrats of the industry, found to their great dismay that they were no longer safe, no longer sure of a job. The clothiers employ now-a-days two expert mechanics while the rest of the force of twenty, or twenty-five cutters are young boys who work for a mere pittance, yet do most of the work formerly performed by skilled cutters.

The coat makers, the second in line, found that women were fast being enlisted to do their work at half the price paid to men, that the work given out to the sub-contractors was done for less than the women did it for, that the brief seasons were getting ever briefer. This because the clothing manufacturers no longer make up stock. Former seasons of over production have taught them a lesson. They get their orders now simply from the samples cf material and make up only as many garments as are ordered.

The vest-makers are now worse off than ever. Since people stop wearing vests in summer the season lasts only about four months in the year, the rest of the time the vest-makers are mostly idle. The influx of women into this branch of the trade, has cut down the prices. A vest maker is hired for as little as the boss can get him to take.

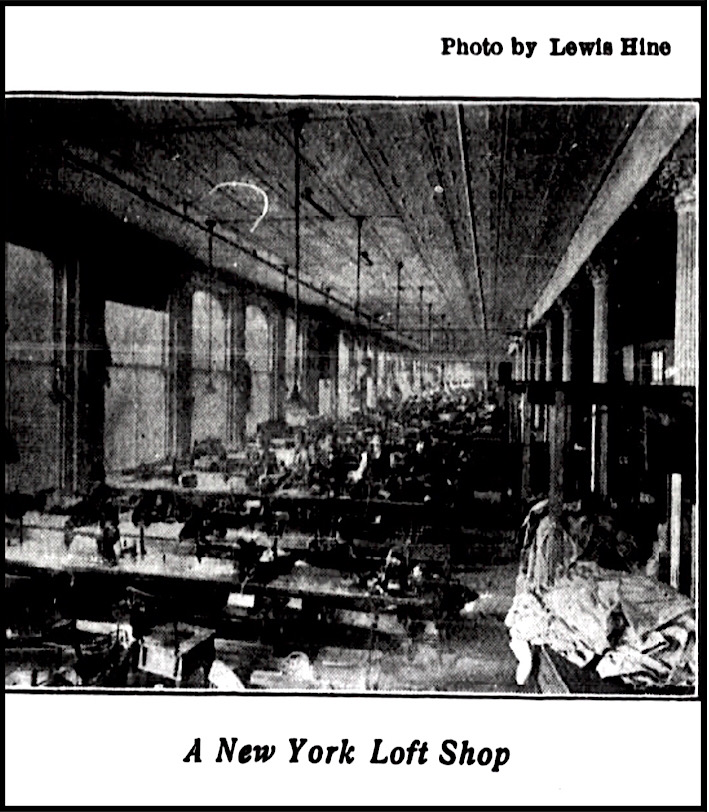

The pants makers, the worst paid workers in the entire industry have always been on the verge of starvation. Their condition is beyond description. They are still at the mercy of the subcontractors who suck the very marrow out of their bones. They work in fire traps, where the broken wooden stairs are usually built around a wooden hoisting shaft which acts as a conductor of smoke and flames. Their shops are dark, dirty; the plumbing is out of order, the hours are most unearthly.

The children’s jackets, knee pants and overcoat makers are paid even less than the workers at men’s clothing. Their complaints are constantly heard, winter and summer, in season and out of season.

As a matter of fact, the clothing industry is from its very inception linked with low wages, long hours, unbearable working conditions. The home work, the small shop system, the great subdivision of labor, which meant the use of unskilled labor were responsible for it from the very start.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote T Malkiel, Sisters Arise, Sc Woman p10, July 1908

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/socialist-woman/080700-socialistwoman-v2w14.pdf

The Coming Nation

(Girard, Kansas)

-Jan 25, 1913

https://www.newspapers.com/image/487678654/

https://www.newspapers.com/image/487678678/

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From The Coming Nation:

Theresa Malkiel on the New York Garment Workers Strike, Part I

Tag: Lewis Hine

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lewis-hine/

Tag: Jewish Daily Forward

https://weneverforget.org/tag/jewish-daily-forward/

The Forward

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Forward

Tag: New York Garment Workers Strike of 1913

https://weneverforget.org/tag/new-york-garment-workers-strike-of-1913/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Working Girl Blues – Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard