———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday November 13, 1919

Intimidation in Pittsburg Steel District Contrasted with Ohio

From The Survey of November 8, 1919:

Closed Towns

Intimidation as It is Practised in the Pittsburgh

Steel District:—the Contrast in OhioBy S. Adele Shaw

[Parts III-V of V]

III

THIS interlocking of mill and town officials explains not only the ease with which normal civil rights have been shelved, but the ease with which, under the guise of law enforcement, deputies and troopers get away with reckless action in the streets and alleys, and with which the petty courts turn trumped-up grounds for the arrest of labor organizers and strikers into denials of justice.

In Allegheny county Sheriff Haddock had, according to his own statement on October first, deputized 300 men for service under control of his central office and 5,000 mill deputies. Newspapers placed the figure early in the strike at 10,000. The mill police who in ordinary times are sworn in under the state provision for coal and iron police for duty in the mills only, are, since the strike, sworn in by the sheriff at the request of the companies. They have power to act anywhere in the county. They are under the direction of the mill authorities. Companies are required to file a bond of $2,000 for each man so deputized and are responsible for his actions.

It is the state constabulary, however, who have set the pace for the work of intimidation in the mill towns of Allegheny county. Responsibility for calling them in is difficult to fix. Since last February squads had been stationed at Dravosburg within easy reach of the steel towns; and the Saturday before the strike patrols were brought down into them. The sheriff denies that he called on the state for the troopers. The burgess of Braddock and the chiefs of police in Homestead and Munhall professed ignorance of the responsibility for their coming.

The Pennsylvania State Constabulary [Pennsylvania Cossacks] has an enviable record in patrolling remote districts, cooperating in preventing forest fires, running down speak easies and gambling joints. In the Westinghouse strike of 1915 they behaved admirably. Their even-handedness then was illustrated when they exposed the act of a business man of East Pittsburgh who had planted a fake bomb in the grounds of the works’ superintendent with the idea of discrediting the strikers. Their action in the industrial conflict now on has seemingly taken color from the unconcealed partisanship of state and local officials. They apparently view the strike as a fire department would view a fire—as something to be stamped out.

Troopers patrol the streets about the mills and in the foreign districts. At a time of excitement legends and rumors as to their activities are to be expected, but there are too many stories confirmed, too many affidavits signed, too many illustrations for the visitor’s own eyes as he goes through the towns to leave any doubt as to the recklessness and prejudice of their actions. One mill town minister with a congregation of nearly a thousand Americans, among whom are many of the mill officials inadvertently said to me:

The mill officials based their hopes on the troopers intimidating-I mean on their quelling any riots—on the marvelous ability of these troops to stop trouble. They created a panic here. Ran terror down the back of the foreigners. Such training! Even the horses. I have seen them myself grip the collar of a man, throw him down, put a foot on him as much as to say, “Now you move, and I’ll crush you.”

In Homestead, I talked with a man, whom I shall call Stef Houdek, of what had happened to him. Then I saw his neighbors and his family and the burgess who was magistrate in the case. Stef had been to see his cousin. On the way home a trooper ordered him into a house which he was passing. “That’s not my house,” the man said he replied: “I go home.” “I’ll take you home!” he said the trooper threatened. The man ran into the house, the trooper chasing him. A woman was boiling clothes at a kitchen stove, her young children about her. She was soon to have another child. The police caught the man, took him to jail, where he was charged with resisting an officer and fined $10 and costs. I was told the woman’s child was born soon after her fright and that she was seriously ill.

Private citizens other than mill workers have suffered from the treatment of the state constabulary. There was Adolph Kueheman, for example. I had the story from Kueheman, from two witnesses and from a man present at the hearing. Kueheman was in Dressler’s saloon in Homestead. The state police were dispersing a group of men who were on the porch of their own boarding house. Kueheman and Dressler heard the excitement and ran out. They had scarcely got out, Kueheman said, when a trooper commanded, “Get in there!” “All right,” replied Dressler. Hardly was the word out of his mouth when the trooper struck him twice, once on the arm and once on the shoulder.

They entered the saloon, Kueheman in the rear. As he passed through the door-way he looked towards the street. The trooper asked him what he was looking at. He replied, “I don’t know.” With that the trooper ran after him into the room at the rear of the bar and struck at Kueheman’s head, but the man put out his hand for protection and received the blow on his arm.

He was arrested and fined $10 and costs. The chief of police, not the trooper, testified against him at the hearing. The chief had been in the crowd. He said Kueheman had not moved quickly enough. Kueheman was not permitted to have his witness, who was present, testify, as the burgess said he had “heard enough” and “hadn’t time to listen to witnesses.” I saw the arms of both men where they had been struck. That of Dressier looked like a large eggplant, so deeply was it bruised. The burgess told me the story I had heard was ridiculous; that the man admitted at the hearing that he had not “moved quickly.” The burgess, how ever, confirmed the story that he had not been willing to hear the witness.

At the hearing’ before the Senate Investigating Committee in Pittsburgh the same sort of story that came to me in the towns was told over and over again by strikers and strikers’ wives from Donora and Monessen and other towns that I had not visited. One witness after another testified that as he left home soon after six in the morning in Monessen and walked down the street alone to the store, to the train or for the doctor as the case might be, he was grabbed by the state troopers, clubbed, taken in an auto “to the Tube Mill gate,” thrown into the cellar, searched, asked if he was a citizen, told he and “the other fellows were going to get hanged about eight o’clock,” held for an hour or so, and then taken to the lockup. Late in the day the men were brought before the burgess and held for court on $500 bail. They did not know with what offense they were charged. There were no papers. “No time to learn nothin’, but I was told ‘if you work alright, if not go to jail'”—this from the testimony of one of the men was typical.

[The testimony] gave some understanding of the reply of a later witness when asked by a senator, “What country do you come from?”

“Galicia,” he responded promptly.

“What’s the difference between the government in Galicia and that in America?”

“Oh, king there. Here, superintendent.”

In some instances, mill superintendents and foremen accompanied the police to the homes of the men to get them to return to work. Duquesne offers an illustration. Five strikers there, according to their statements and the statements of neighbors with whom I talked, were sitting on their porch the first day of the strike. The assistant general superintendent accompanied by mill deputies and the town chief of police, came up the street and asked the men if they were going to work. The men replied that they were not. Where upon they were arrested, charged with disorderly conduct, fined $27.75 each, and their union cards taken from them. The chief of police told me the men had been fighting.

At the South Side police station in Pittsburgh as many as thirty-six men were rounded up in a single morning. There, lawyers for the strikers were not permitted to see their clients previous to the hearings, charges were mumbled so that the auditors could not hear them and one lawyer was expelled from the court for protesting. From my talks with the men in every town and from repeated testimony at the hearing of the Senate committee the fact stood out clearly that if strikers said they would go to work they were let go; if not they were given “ten dollars or ten days.” In the majority of cases the men did not know with what offense they were charged.

And these acts I found backed up by mill officials everywhere. Their attitude was that the troopers had made a good job of it and saved a desperate situation for them. Talking over what I had seen with a spokesman for the Carnegie company, he said, “Yes, these things have been done. And even so hard-shelled an official as I am ready to say we have done more. But if we hadn’t we’ve have had all the mills closed down and a revolution on our hands.” He was not ready to say what he thought might be the result of such methods in five years in Duquesne for example.

“The situation was on us and we had to deal with it,” he said. Then I asked him for evidence of revolutionary material. He said he had had none prior to the strike but handed me what he had received since—a bill distributed he said in Braddock and in Lawrenceville, Pittsburgh. It was an appeal to the Americans not to be scabs. It had not been authorized by the strike committee. I have kept in touch with the literature of the committee in the Pittsburgh district through out the summer. In it they have consistently opposed violence on the part of the strikers. Their bulletin issued October 3, during the strike, illustrates this.

It reads:

The American Federation of Labor has grown to its tremendous size and won its enormous power by respecting the law. We shall win this fight by the same methods. All you have to do is to stick and obey the law.

The Carnegie official just quoted, when asked about intimidation practiced by the strikers, told me workers and their wives had complained to the foremen that strikers had threatened their homes and their lives if they went to work. I had found it impossible to get these charges from local mill officials since they refused to talk, but referred me to the city office of the company. So I asked this official at the office of the president, for the name and address of even one case to follow through. He said that a number of threatening letters written in foreign languages—”perhaps a dozen”—had been forwarded to Judge Gary, who had presented them as evidence before the Senate committee. But he added that the company had no proof that any of the letters had been written by union men. There were no copies in the office, he said. On two different visits I was unable to get any case of intimidation to follow up. In McKeesport and North Braddock men had been arrested charged with verbally threatening workers and calling them scabs.

In weighing these charges the general social composition of the mill towns must be borne in mind. The steel mills depend for from one-half to two-thirds of their force upon unskilled and semi-skilled labor for which they have for years drawn on newer and ever newer waves of immigration. “American” in the steel towns does not mean native born. It designates the man who speaks English on the street. And there is almost as big a gap between these “Americans” and the foreigners (aliens who cannot speak English) as between them both and the merchants and office holders, mill officials and skilled workers who make up the older resident groups.

At a time of industrial tension the world over, of race riots in our larger cities and loose denunciations leading to mistrust and bitterness, strike leaders have had no easy task to carry through a great mass movement without friction. After two weeks in which I talked with public and mill officials, with strikers both foreign and American, with outside labor organizers and men who had been in the strikes of the ’90s, with non-union men and men still at work, with ministers, businessmen and wives and mothers of steel workers, I came away with the same picture of each town I visited: the officials in violation of individual rights and of the law and backed by local public opinion, acting with one aim—to get the men back to work; the strikers, against such odds, doing their best to win public confidence.

The picture is one of barbed wire entanglements to civil liberty, with a smoke screen of newspaper distortion thrown over it, spreading fear among the strikers and preventing sympathetic understanding of their cause. With outdoor meetings prohibited throughout the country; indoor meetings checked in many of the towns; halls and lots taken over by subsidiaries of the steel companies; picketing prohibited in many districts, and even groups of men on their own property dispersed, normal avenues for discussion as the basis for common action were closed. In their stead was this systematic policy of intimidation which only by a stretch of the imagination could be construed as suppressing disorder. It was clearly to break the strike.

Father Kazency [Father Adalbert Kazincy], a Catholic priest of Braddock, telling of the attack of state troopers on members of his church—chiefly strikers’ families—as they came out from a “mission” held the Sunday before the strike, said:

It was a magnificent display of self-control on the part of the men. They moved on after the threats and the clubbing of the police, with heads lowered and jaws firmly set. Oh, it was great. It was wonderful! They, those husky, muscle-bound titans of raw force, walked home, only thinking, thinking hard. They wanted to win the confidence of the town.

IV

From this scene of repression I went early in the fourth week of the strike over the line into Ohio—”from Siberia into America.” as the strikers say. For every other day they cross, from 3,000 to 5,000 of them, marching two miles or more from Farrell, Sharon and Sharpsville in Pennsylvania, where they are not permitted to meet, to an open field five hundred feet over the Ohio line. There, undisturbed by the Ohio authorities these men listen eagerly to their leaders who come armed, not with guns, but with a fresh store of tales of outrages committed by the Pennsylvania authorities. The effect of these is not only to act as a brace to the strikers in their present stand; no one who has talked with the men can fail to see that the situation is storing up in them a sense of mockery for the government, or at least for those who are entrusted with its direction in western Pennsylvania.

It is well for America and the future of her institutions that there are states like Ohio, demonstrating the workings of democracy and offering hospitality to strikers to discuss their grievances.

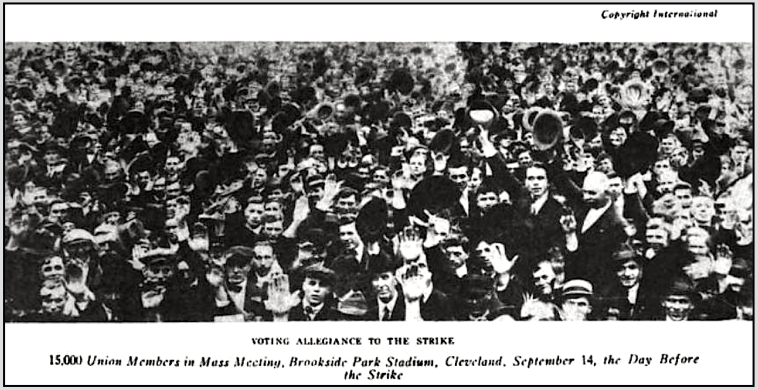

In Ohio, I found the answer to the contention that Pennsylvania’s action was necessary to prevent riot and revolution among the steel workers. There were no state troopers to be seen in Ohio’s steel towns the fourth week of the strike. She has no state constabulary. There were few special deputies in comparison with the Pennsylvania towns. I traveled through the cities unmolested, un-“watched.” Strikers were enjoying their rest, were picketing before the mills or otherwise going about the business of their strike. Local authorities were busy maintaining order through the same channels as in times of industrial peace. Mass meetings, both during the organizing campaign and during the strike, have been held freely. The stadium in Cleveland where fifteen thousand strikers have gathered at a time, the parks, the theaters all were used generally. Not one speaker had been arrested in Youngstown, Cleveland, or Steubenville. Not one meeting dispersed. Officials there reported that no trouble of any kind had resulted.

A professional man in Cleveland told me he didn’t think of the strike as being in Ohio. “It always seems to me it’s in Pennsylvania,” he said. Yet practically every mill in his city was “down flat,” while Pennsylvania had the highest production of any of the strike districts.

When I arrived in Steubenville the streets were thronged with crowds of merry makers enjoying old home week and a welcome celebration for returned soldiers. Strikers joined in heartily with merchants and clerks on a holiday. Not a stack was breathing at the mills. Both the La Belle Iron Works and the Weirton Steel Company inside the city limits were closed down. Even the superintendent of the iron works had gone with his family on a vacation.

“Any trouble here?”I asked the mayor.

“Not a bit,” he replied.

“How many extra police did it take?”

“I haven’t one.”

“And the sheriff?”

“He hasn’t sworn in a man.”

“But your arrests—suspicious persons-carrying arms-riot and all that?”

“Our arrests have been below normal since the strike”

“You mean perhaps they have been lower since the dry law, July 1?”

“I mean they have been lower since September 22 [the day the strike began] than at any time since July 1.”

“We haven’t had an arrest in connection with the strike,” said the director of public safety.

“We picket the mills twenty-four hours a day and haven’t had even so much as a fist fight,” said Wilson, organizer for the iron and steel workers.

Over in the Herald Square Theatre strikers had gathered for an afternoon meeting. Scarcely had I recovered from my surprise at seeing them admitted to a public building of such stand ing when I was told the men frequently held meetings in the courthouse. I tried to picture strikers in a courthouse in western Pennsylvania for any other purpose than to be fined for daring to hold a meeting at all.

I would not convey the idea, however that the stand taken by the Ohio authorities has left no difficulties in the way of either the strikers or the employers. It has. There was the Lorrain outrage—an isolated case. The Ohio organizers charged that the president of the new local of the Amalgamated at Lorrain, for trying to hold a meeting, was blindfolded, tied hands and feet, taken fifteen or eighteen miles out of the city by the mill police of the National Tube Company, and thrown into a creek. There are East Youngstown and Struthers where special deputies, many in uniform, stand on guard before the mills displaying their guns. In these towns the sheriff, Ben Morris, holds sway and the strikers say they cannot count on him to play fair.

Employers, on the other hand, gave me to understand that they had not enough police protection. They all pointed to the Pennsylvania state constabulary and said that was what Ohio needed. When I asked why, two instances of trouble resulting from picketing were cited to me—one in Youngstown and one in Cleveland—in which several workers and strikers were injured, but the recurrence of which the public officials prevented. They were practically the only affairs of any consequence that had occurred to date in the state. Both were early in the fourth week, following the announcement in the papers that the mills were going to open up.

Employers also told me of cases of intimidation of workers. At the Ohio works of the Carnegie Steel Company in Youngstown the superintendent showed me thirty affidavits they had secured to this effect. They told of warnings that homes would be burned, live stock killed, and even threats against the lives of women and children if the men went to work. Practically none of these affidavits, however, gave names of those making the threats. In one case where such names were given I visited the woman who had made the affidavit—the wife of a man blinded in one eye in the mills who was afraid he would not get a job elsewhere if he quit work. When I asked her as to the threat, she answered the men “didn’t mean nothin’.”

The general maintenance of order in the Ohio towns has been brought about chiefly through the cooperation of public officials with labor no less than with mill authorities. While I was talking with an organizer at labor head quarters in Cleveland, a representative of the sheriff entered—not to make arrests or to close the offices—but to ask the organizer to go with him to disperse the crowd of strikers who had gathered before the gates of the American Steel and Wire Company at Cuyahoga Heights—a contrast to the methods of the constabulary and deputies in Pennsylvania in dispersing strikers.

In Cleveland, Mayor Davis has announced he will not permit strike-breakers to be brought into the city. During the first strike week, 59 strike-breakers came in on a train from Detroit. They were met by the police, taken to headquarters, questioned, and given the alternative of returning to Detroit or going to jail. The action was based on the city ordinance covering suspicious persons and was taken “to prevent riot.” One hundred and thirty-three such persons were given the same treatment the day I left Cleveland.

The question of the importation and deportation of persons to and from strike towns is one of the nice problems which the strike has brought to the fore.

Arrests in Youngstown I found to be about normal—the first week of the strike 110, the week from October 7-14, when the tension was higher, 191. This in comparison with a weekly average of about 150 over the summer. Of a total of 60 persons held on suspicion from September 22 to October 14-probably strike arrests—but ten were held over the three-day period, at the end of which time, according to the law, the suspect must be arraigned and a charge preferred against him. Of the ten held, charged with carrying arms and now out on bail, more than half were workers entering the mills. Contrast this with the record of police courts in Newcastle, just across the line in Pennsylvania, where those arrested on suspicion were being held “until the strike is over” and could not get bail and where men were released if they promised to go to work. Forty were so held in Newcastle the first week of the strike.

An interesting evidence of the value of real cooperation on the part of civic bodies with the authorities in maintaining order was that of the American Legion in Youngstown. Following the offering of their services to the mayor, so much opposition developed because of the number of union men among the membership that the legion decided to define its position. It would assist in the maintenance of order in the city but not in any effort to break the strike. It asked for a member of the central labor body (not the strike committee) to meet with its committee weekly.

The result has made for understanding. The ex-service men patrol only the residence districts. Their weapons are under cover. On their arms are white bands designating them as legion men and the strikers know what that means, because of the attitude of fair play the legion has publicly taken. The organization has been active in eliminating the bringing in of strikebreakers. They were successful in getting the mill owners to agree not to employ men in uniform as guards at the mills, and in getting three of the mills—the Sharon Steel Hoop, the Republic Iron and Steel and the Brier Hill Steel—to agree not to attempt to bring in out of town guards from private detective agencies. They are not, as the Newcastle papers said of the Newcastle men in uniform, “out having fun.” They are constantly trying to avert trouble in a serious situation.

V

OHIO, then, I would picture as a state in the midst of a strike where constitutional rights of assemblage and free speech have not been tampered with by public officials and where the courts are functioning normally; where the mills have been free to hold or win back their men but where the men have been free to organize and where in some places they have done so nearly 100 per cent; where strike excesses have been reduced to a minimum largely through the unprecedented educational campaigns of the strike committees, who reached their men because they were permitted to hold meetings; where justice is not a stranger to the courts; where strike issues have not been befogged by the higher issues of constitutional rights;-a state in which the governor set the pace for action of local authorities in declarations throughout the strike, which, whether one agreed with him or not, made for confidence in all sections of the population rather than for reckless license in one and almost desperate hopelessness in another.

In an address given in Columbus, October 15, Governor Cox said:

There are two outstanding features of the situation. One is an insidious movement to establish a soviet [Bolshevik?] regime in America. The public mind will dissociate it from any enterprise with which it is mixed and then stamp it out. Another very obvious thing is the harvest that some captains of industry are reaping from their own planting. Aliens by tens of thousands were thrown into the mills, poorly housed and little or no attention paid to their Americanization. Too many people have been more interested in dividends than in patriotism. The duty of government now is to deport every revolutionist and to compel industry where aliens are employed, to pay more attention to some things aside from the exclusive affair of the day’s labor. We have had our lesson; it is time we begin to profit by it.

In a manifesto issued to local authorities, on October 16, he said:

No man, must be permitted to define the rules of his individual conduct. The law is supreme. I shall expect its enforcement by local officers: When they have rendered their utmost effort and failed to meet conditions, then the state will act promptly.

Speaking of the foreigners at the same time, he said:

They are not familiar with our laws, but it is safe to assume that the individual conscience tells every man that violence is both a moral and a legal wrong.

[Governor Cox further said:]

Picketing as we understand it, is neither prohibited by law nor condemned by public sentiment, but it must go no further than moral persuasion…Throughout the years the policy has been not to make use of soldiers nor policemen to man street cars, for instance, nor to in any way make of them the instruments to bring a strike to an end. If either state or local officers provided safe conveyance of workmen into or out of a manufacturing institution, the government would be making of itself the agent of one of the parties to the dispute.

This is in contrast to the attitude of Governor Sproul of Pennsylvania who, the same day in an address in Erie, lauded the action of the state constabulary, in the face of protest lodged by the president of the State Federation of Labor against the “outrages, injustices and crimes” of the state constabulary and other public officials in the western part of the state. Governor Sproul has supported the county, sheriffs in prohibiting the gathering of strikers.

Of the foreigners he wrote:

The danger comes not from the English-speaking workmen but from the foreigners of the community, who have neither sympathy for our policies nor interest in our institutions. Tradition means nothing to them, and lawlessness and disorder are “music to their ears” and a realization of their fanciful dreams.

In his testimony before the Senate committee, Judge Gary declared it to be “the opinion of the world that open shops mean more production, better methods and more prosperity, that closed shops mean lower production and less prosperity.” Where, in the estimation of Judge Gary, does the opinion of the world stand on the closed town?

[Photograph of Cleveland Meeting added. Emphasis and paragraph breaks added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGE of Mother Jones with Organizers

Quote Mother Jones, Strikes are not peace Clv UMWC p537, Sept 16, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=-V5ZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA537

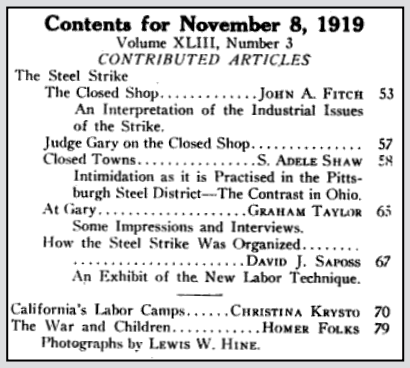

The Survey, Volume 43

(New York, New York)

-Oct 1919-March 1920

Survey Associates,1920

https://books.google.com/books?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ

–Survey of Nov 8, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA51&pg=GBS.PA51

“Closed Towns” by S. Adele Shaw, Parts I-II of V

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA58

“Closed Towns” by S. Adele Shaw, Parts III-V of V

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA64

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA87

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA92

IMAGE

GSS Vote to Strike at Cleveland, Survey p65, Nov 8, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA65

See also:

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday November 12, 1919

“Closed Towns” by S. Adele Shaw for The Survey: Intimidation in Pittsburgh Steel District

Tag: Great Steel Strike of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/great-steel-strike-of-1919/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Never Cross A Picket Line – Billy Bragg