———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday November 12, 1919

Intimidation as Practiced in the Pittsburgh Steel District

From The Survey of November 8, 1919:

Closed Towns

Intimidation as It is Practised in the Pittsburgh

Steel District:—the Contrast in OhioBy S. Adele Shaw

[Miss Shaw spent the first two weeks of the strike in the Pittsburgh district for the SURVEY, and then crossed from Pennsylvania to the steel centers of Ohio, where civil liberties are preserved in the midst of the industrial conflict. A native of Pittsburgh, member of the staff of the Pittsburgh Survey, Miss Shaw brings experience as a social worker and as a journalist to her task of interpretation. The first draft of her article was submitted for criticism to public officials, strike leaders and mill executives. Facts were then checked up and incidents carried to their sources, and her narrative can be depended upon as the findings of a trained observer.—EDITOR.]

[Parts I-II of V]

I ARRIVED in Pittsburgh the evening of the third day of the steel strike [September 24th]. Through a gate to one side of me, as I stood in the Union Station, a line of foreigners perhaps twenty-five in number, Slavs and Poles, dressed in their dark “best” clothes, with mustaches brushed, their faces shining, passed to the New York emigrant train. Each man carried a large new leather suitcase, or occasionally the painted tin suitcase—a veritable trunk—appeared in the line. And there, not quite concealed by its wrapping, was the unmistakable portrait which one could picture in its setting over the mantle in the boarding-house just left. Men and baggage were leaving, as every night they leave from that station on that same train for New York and the “old country.”

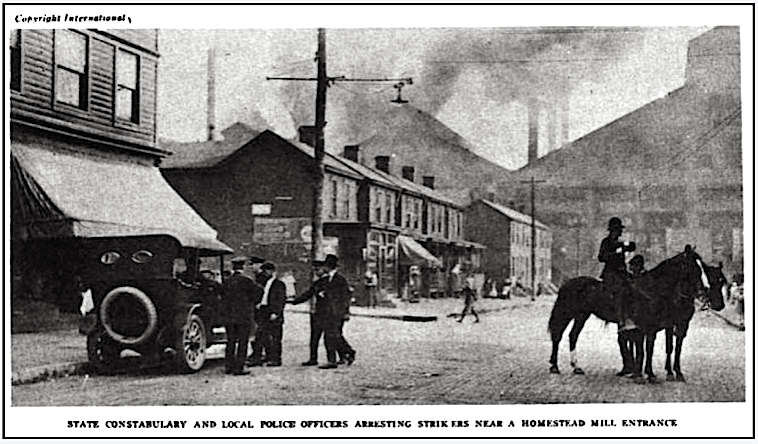

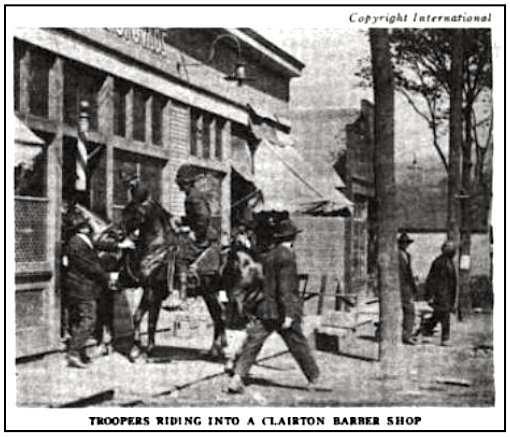

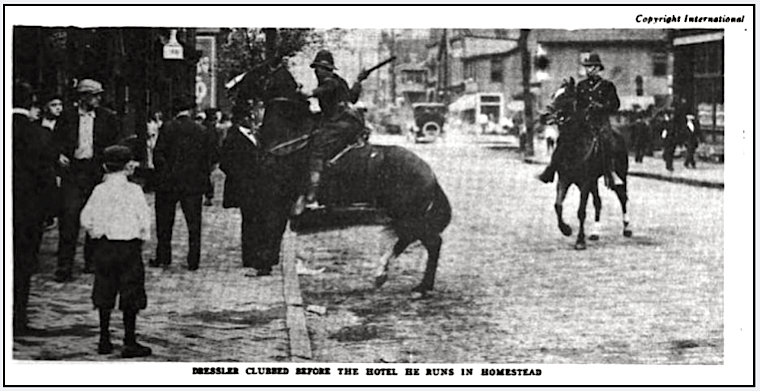

Scarcely had the gate closed on the emigrant workers when a guard threw open an entrance gate through which marched, erect and brisk, a squad of state constabulary “Cossacks” they are called in the mill towns. Young men they were in perfect training—men with great projection of jaw developed, it almost seemed, to hold the black leather straps of their helmets firmly in place.

It was the following day that I came in closer contact with one of these troopers in Braddock, the town where the foundation of the Carnegie fortune was laid. I had been at labor headquarters and then, before calling on the town or mill officials, walked with the local head of the Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers, down the street to see the mill with its protection of walls, guns and men. We neither stepped off the sidewalk of the main thoroughfare nor stopped as we looked at the mill on one side and the homes of workers on the other. We made no notes and spoke to no one we passed. Yet as we turned the corner, a trooper pushed the nose of his horse to my shoulder, dismounted and ordered us to stop. He searched the organizer and asked what he was doing in the town. The man presented his card.

“If I catch you loitering here one instant I’ll arrest you.” The jaw was unusually long.

“And you, too,” he snapped, turning to direct his attention to me.

“What are those pamphlets you are distributing?” He took the papers and book I carried.

“The Pittsburgh Sun and Chronicle Telegraph,” I replied.

Corporal Smith took from me my book, my personal papers, a telegram of instructions from the editor of the SURVEY, the notes I had made on my visits to the towns, cards with addresses, etc. He returned my book and mounted his horse.

“When may I have my papers back?” I inquired. “That’s my business,” retorted the corporal.

I.

INTIMIDATION, not riot, is the word to describe the situation as I saw it the first week of the strike in the mill towns of western Pennsylvania. In addition to Braddock I visited Homestead, McKeesport and Duquesne in Allegheny County. Over each town hung an atmosphere heavy with suppression—a suppression personified on the surface by the troopers, but which dates back to ’92, when the Carnegie Company under H. C. Frick broke the back of the union—a suppression engineered by the interlocking machinery of mill, town, county and state. It is this combination that the strikers are up against. It is the core of the present struggle. It explains more than any thing else the demand of the workers to be heard—to be free men—free in their towns as well as in their work.

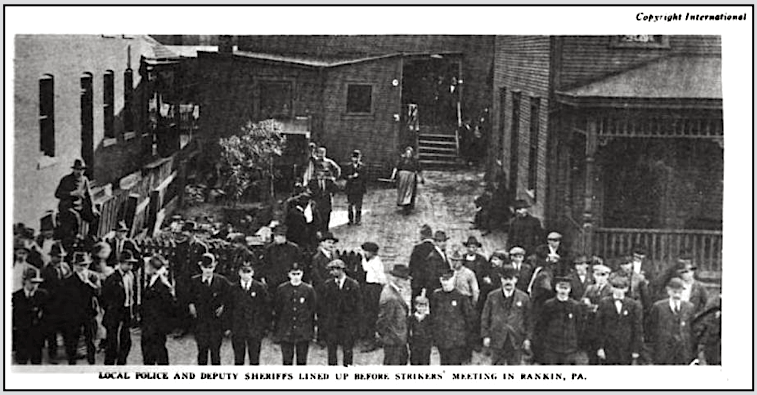

Backed by governor, sheriff and mayors, the iron will of the steel corporations has been clamped down upon the men at every turn in this, their first effort at self-assertion in from ten to thirty years. Two days before the strike was called, William S. Haddock, sheriff of Allegheny county, issued a proclamation prohibiting the gathering of three or more persons on highways or vacant property, and ordering the dispersing of persons “unlawfully, riotously and tumultuously” assembled together. This proclamation under the sheriff’s own interpretation prohibited all outdoor meetings, the making of remarks derogatory to public officials and the expression of “radical” sentiments. The interpretation of the words “derogatory” and “radical” he left with town officials or his local representative.

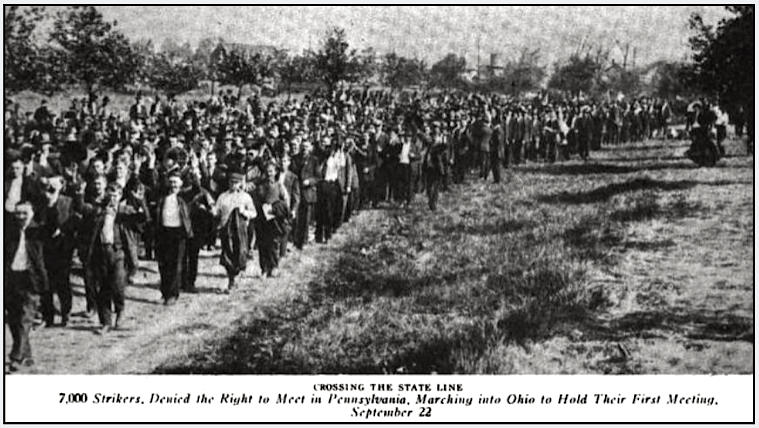

Despite this order, strikers have attempted to hold outdoor meetings, basing their action on their constitutional right to freedom of speech. Early in the first week a thousand of them crossed the city line from McKees port into Glassport borough at three in the afternoon. Glassport authorities did not protest, but seven of the state police and county deputies appeared, dispersed the men, and arrested the leaders on charge of riot. The toll was four injured. Since that time the sheriff has prohibited the holding of any meetings in Glassport, indoors or out. Asked why he had taken such action when the Glassport authorities had not objected to the meetings, he said that since the mayor of McKeesport had prohibited meetings it “would not be fair to him if the sheriff did not prohibit them in the adjoining borough.”

In North Clairton, just beyond, strikers were holding a meeting the Sunday before the strike in a field where local authorities had, previous to the sheriff’s proclamation, given the men permission to meet. The meeting was proceeding peaceably when suddenly seven or eight troopers broke it up and took five men under arrest. Thirty-six more of the men were arrested a day or two following the meeting. The majority were held for “in citing to riot.” Bail was placed at from $1,000 to $2,500 and pending the hearings ten days later, the men had to put up a total bail of over $43,000.

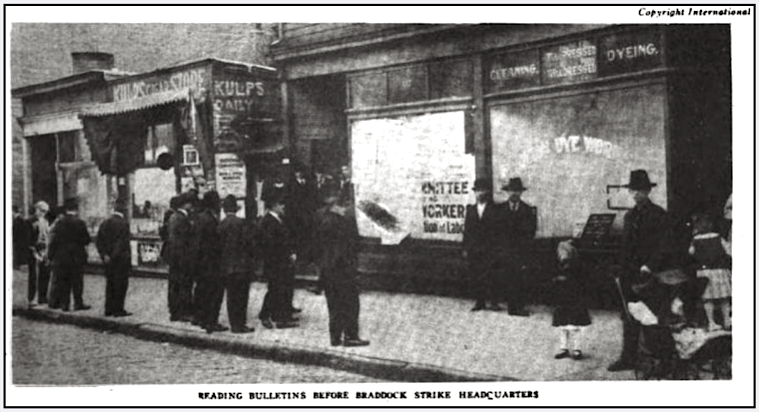

In Braddock, both outdoor and indoor meetings had been held previous to the sheriff’s proclamation. At the first attempt, during the summer, the organizers had been arrested to be sure. But at their hearing Squire Holzman said he “refused to do the dirty work of the burgess.” The men were released. During the strike, indoor meetings continued. So Braddock afforded me not only fresh impressions of a steel town in the midst of the strike but also of the sort of strikers’ meetings prohibited in other boroughs which did not share in even Braddock’s restricted measure of industrial liberty.

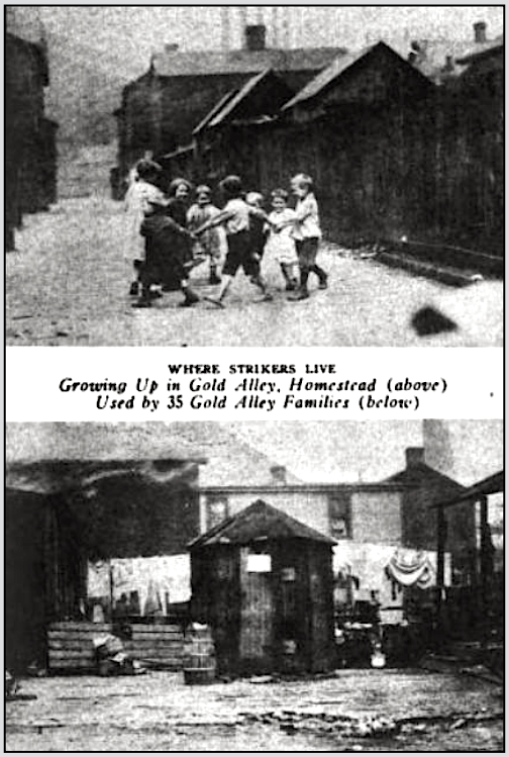

Braddock lies on the right bank of the Monongahela just below McKeesport and across the river from Homestead. It is the typical steel-mill town, with the works on the level by the river, the foreign districts close about, the railroad and steel car lines running through the business sections, dividing the industrial district from the residences of Americans and officials on the hillside. There are the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, the original plant of the Carnegie Steel Company, where Carnegie and Schwab got their start; the Carrie furnaces of the same company which makes metal for the Homestead works; the American Steel and Wire Company, a subsidiary of the corporation, and the McClintic-Marshall Construction Company, called by labor organizers “the greatest labor hating concern in America.”

“No trouble here at all” was the invariable answer from town and mill officials when asked how things were going. A cold dead calm had descended upon the town. The stacks of the mills seemed scarcely breathing. The air was cleared of dust and soot and the blue sky shone above. Along the main street a steady stream of foreigners passed—not loitering nor in groups—but walking seemingly in full enjoyment of their right to be dressed up and look at the shops or partake of the town’s amusements, yet on the alert. To many of them it was a new experience. They had christened the first day of the strike “Labor’s Day.”

Yet police and plain clothes men were everywhere in evidence and an occasional trooper passed on his horse.

Nearer the Edgar Thomson works the state police, who earlier in the day patrol the foreign districts, were guarding the men who came out. I saw but a handful—perhaps twelve—young men and Negroes, with their dinner buckets, their faces smirched with soot. At the entrance to the works the mill police stood on watch on the porch of the guard house, guns at their feet. Deputies and plain clothes men stood by. Troopers patrolled up and down before the high concrete wall with its iron gates—a wall which gives the mill the appearance of a medieval town. Behind the wall the mill officials and the majority of the workers—many of them Negroes—worked, slept and ate. Where the railroad tracks enter the mill, two small wooden guard houses had been erected. The front walls were of wood below and corrugated iron above. Between the two materials there was an open space perhaps two feet wide, through which the deputies could be seen. In these shacks on either side of the tracks the strikers believed machine guns were set for action. Below the tracks, the street opposite the mill and those leading out from it were lined with workingmen’s houses. Children played on the filthy bricks and in the dirt by the curb.

In the evening I went to a meeting of strikers. All was quiet as I made my way toward the river. Down a poorly lighted street, so dark I could scarcely see the curb, I found the men standing, filling the vacant lot before the door of the hall which was packed, and on the sidewalks and street, but not blocking either. There was neither noise nor excitement. “Mother Jones goin’ to speak.” “Come on, lady.” And the men held up their arms to open a passage for me. The hall was jammed. Sweat stood on every forehead.

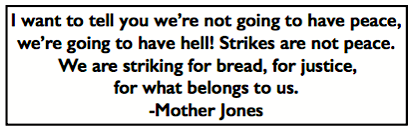

The first speaker was J. G. Brown of the Pittsburgh strike committee. I had heard him the summer before in the mill towns telling the men what the eight-hour day would mean for them and their families, urging them to take out their papers and become citizens, and never failing to impress upon them the necessity of obeying the laws of the town, state and the country. Then came the deep clear voice of a woman, filling every corner of the hall. I stood on tiptoe and saw the grey hair of Mother Jones, the woman agitator of the mining districts of Colorado and West Virginia, who with the rough speech and ready invective of the old-time labor spell binder, has exerted a powerful influence over the striking steel workers. At her first words there was complete silence. Though practically all were foreigners, not a man in the hall appeared to miss a word.

[She said:]

We’re going to have a hell of a fight here, boys. We are to find out whether Pennsylvania belongs to Gary or to Uncle Sam. If it belongs to Gary we are going to take it away from him. We can scare and starve and lick the whole gang when we get ready…The eyes of the world are on us today. They want to see if America can make the fight…Our boys went over there. You were told to clean up the Kaiser. Well, you did it. And now we’re going to clean up the damned Kaisers at home…They sit up and smoke seventy-five cent cigars and have a lackey bring them champagne. They have stomachs two miles long and two miles wide and we fill them…Remember when all was dark in Europe and Columbus said, “I see a new land,” they laughed. But the Queen of Spain sold her jewels and Columbus went to it…He died in poverty, but he gave us this nation and you and I aren’t going to let Gary take it from us…If he wants fourteen hours he can go in and work it himself…We don’t want guns. We want to destroy guns. We want honest men to keep the peace. We want music and play grounds and the things to make life worth while…Now, you fellows go on out. I want to talk to the other boys.

II.

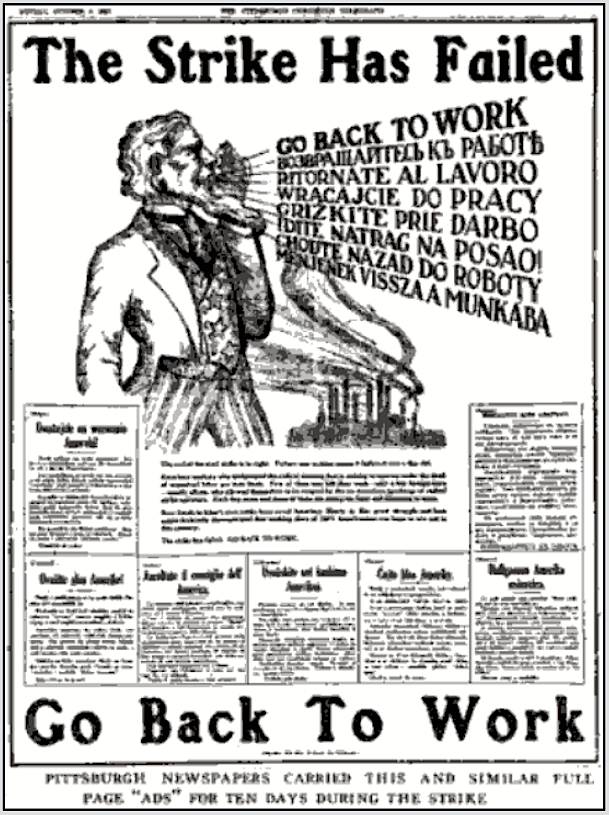

WHAT the sheriff’s proclamation did in balking outdoor meetings throughout the county, local officials in other mill towns did for just such indoor meetings as this at Braddock. In Pittsburgh itself Mayor Babcock prohibited the holding of meetings “within the strike zones,” limiting them to the Labor Temple in the center of the city (Pittsburgh car fare is 10 cents straight or seven and a half cents with tickets) and to one hall on the north side. Pittsburgh council refused the petition of 100,000 organized workers of the district, made through their attorney, to hold a public hearing on the action of public officials during the strike.

The crux of the situation in the mill communities lies in the fact that under the Pennsylvania law the mayors of the towns and the burgesses of the boroughs, though not exactly judges and executioners, are close to it. They are both magistrates and heads of the local government.

James S. Crawford, mayor of Duquesne, effectively blocked the holding of labor meetings, both before and during the strike, outdoors and in; blocked even the opening of headquarters by the organizers. During the second week, Judge Richard A. Kennedy of the Allegheny county court handed down an opinion sustaining his action in fining two organizers, Foster and Beaghen, $100 each for attempting on September 7 to hold a meeting in a vacant lot without a permit. The men had previously applied for a permit and been denied by Crawford. The owner of the lot had given permission to hold the meeting. When the men appeared however, “no trespassing” signs had been put up. The lot had in the meantime been acquired by the Carnegie Land Company. In making the decision the judge held that although the right of free speech is sacred, deserving protection, there are cases in which this right must yield to the safety of citizens, their homes and their property.

[Judge Kennedy] conceded that the object of the meeting, to increase the membership of the American Federation of Labor, was lawful, but said there were times and circumstances which might cause such a meeting to terminate in action which could not be foreseen and which might be disastrous. He held that the mayor was justified by the fact that he was responsible for the preservation of peace and order, although the attempt to meet was two weeks before the strike was called and no trouble had occurred in the city.

Forty workers present at the meeting were arrested and fined from $10 to $25 each. Since the meeting organizers have been unable to lease any vacant lot or any vacant room for headquarters in the town. Their inference is that the Steel Corporation has directly or indirectly leased all such holdings.

It was Mayor Crawford who in denying a permit to the organizers said, “Jesus Christ himself couldn’t hold a meeting in Duquesne.” And it was to this same town that the Committee on Public Information of the federal government, while conducting an Americanization campaign last February, sent a Russian speaker to talk to the people on the life of Abraham Lincoln. At eight o’clock, when on the platform, the speaker was arrested by the local authorities and jailed for three days. It was there, too, that Mayor Crawford, in convicting J. L. Beaghen, one of the organizers arrested for attempting to hold the meeting referred to above, said publicly, “If I had my way you would be sent to the penitentiary for 99.years and when you got out you’d be sent back for 99 years more.”

Mayor Crawford is president of the First National Bank of Duquesne. His brother is president of the McKeesport Tin Plate Company.

It is to such disinterested hands that Sheriff Haddock’s proclamation and Judge Kennedy’s opinion turn over the broad provisions of civil rights in the American constitution. It is to such hands as those of Mayor George H. Lysle, of McKeesport, whose activity began back in April, 1918, when the local labor people attempted to organize the iron and steel workers. [See the SURVEY for January 4.] This was before the St. Paul convention at which the American Federation of Labor set going its present movement for organizing the steel industry. The initiative was taken by the Central Labor Council of McKeesport. They rented Ross Hall and placed cards announcing the meetings in saloons and other places. The mayor ordered the cards removed and notified the meeting that it could not proceed. The men then moved down to the Labor Temple, headquarters for the labor council. There the superintendent of the Portvue tin mill (McKeesport Tin Plate Company, an independent concern), commonly spoken of among residents of the town as the “gold mine” because of the wealth it has produced, barred the door and a scuffle ensued resulting in the arrest of several of the men.

The next move was when the Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers attempted to secure a permit for a meeting in the city last spring. They were refused. Charles H. Howe, president of the central labor body and a member of the town council, tried to put a resolution through council calling for permits to be issued to the organizers. His resolution was not even seconded.

The mill police then appeared on the streets and in saloons, watching the men who were active. The organizers held several street meetings without a permit and finally last July were granted a permit for a hall provided the meetings were held under the auspices of the local Central Labor Council and that no foreign speakers were used. The organizers would not go on record in regard to foreign speakers. Meetings were held Foreign speakers were used. The outstanding feature of all the meetings was the gathering of literally hundreds of mill bosses before the doors to intimidate the men and check them off. I was present at the first meeting when 250 superintendents and foremen stood for three hours outside the hall. After one such meeting 114 men were discharged in one day. From the records at labor headquarters it is estimated that over a thousand men were paid off in a few weeks.

Late in August the mayor again placed the ban on all labor meetings. He took no action, however, in regard to the congregating of officials on the streets before the halls. Tuesday evening after Labor Day the men tried to hold a meeting without a permit. The police interfered and arrested the organizers. They were released on forfeit but the crowd of laborers went down to the Tube mill and called a miniature strike. Trouble resulted. One manager was struck on the head and some of the strikers were injured. The men were chiefly foreigners and many of them were aliens. The report was circulated that quite a few of them were armed. Sheriff Haddock of Allegheny county, who had been called to the scene, told me the men were not armed. Nevertheless, from that time on public sentiment was more than ever against the men.

In addition to bringing in the state police, Mayor Lysle deputized 3,500 men. The climax came however when, during the third strike week, he closed labor headquarters which had been used as a meeting place for the Central Labor Council and local trade unions for nearly thirty years. It was also the strike headquarters. The mayor stated through the press that he closed the rooms because thirty-four men had congregated there, contrary to his proclamation. The thirty-four men had previously been arrested or had suffered injury at the hands of the state constabulary and were stating their cases to a Pittsburgh attorney. The mayor later granted special permission to the carpenters’, bricklayers’ and other “regular” unions to continue the holding of “business” meetings in the building.

Over in Homestead where meetings have been held during the strike the struggle was a free speech fight from the beginning. There no labor meetings had been held for twenty-six years—not since the memorable strike. When organizers went into the town last spring they were denied permits to meet in halls. One had been rented and paid for. The check was returned, the owner making an excuse for the hall’s not being available. The organizers then held two street meetings undisturbed. At the third they were arrested, charged with violating a borough ordinance regulating traffic, and found guilty by the burgess. The case was carried to a higher court, and during the second week of the strike the burgess was sustained by Judge Kennedy.

While the case was pending, verbal permission was granted to hold hall meetings on condition that no foreign speakers be used. Here, too, the organizers refused to go on record on that point. One night there were speeches in foreign languages and after that the permit was refused.

An organizer for the Amalgamated Association then went in and requested a permit. He also would not agree to eliminate foreign speakers and was refused a permit. He then had a writ of mandamus served on the burgess to compel him to issue one. At the hearing before Judge Swearingen in the county court, the burgess protested he had no legal authority to issue a permit for a hall meeting, and thereby admitted he had no authority to deny one. This was the admission sought by the organizers. The case was dropped and they held indoor meetings thereafter without permits.

Maguire, the burgess, practices law in Pittsburgh. He worked in the mill when a young man and was formerly opposed to the methods of the Steel Corporation. He is commonly credited with having been proprietor of a newspaper run for a short time in the borough, which frequently attacked the corporation. Since obtaining office two years ago, however, his opposition has entirely disappeared.

The president of the borough council, “Dick” Moon, who acts as burgess in the absence of Maguire, is chief of the mechanical department in the Carnegie mill. He refused to act in the matter of granting permits for meetings previous to the time the matter was carried to the county courts. At that time he told me it was “too big a matter for him to act upon in the absence of the burgess.” Moon, a Scotchman, was one of the strikers in ’92. Burgess Lincoln of Munhall borough, where the Homestead works is located, is also a superintendent in the mill. Sheriff Haddock’s brother is a mill official at Farrell.

[To be continued.]

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Mother Jones, Strikes are not peace Clv UMWC p537, Sept 16, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=-V5ZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA537

The Survey, Volume 43

(New York, New York)

-Oct 1919-March 1920

Survey Associates,1920

https://books.google.com/books?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ

–Survey of Nov 8, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA51

“Closed Towns” by S. Adele Shaw, Parts I-II of V

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MoEbAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA58

See also:

Tag: Great Steel Strike of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/great-steel-strike-of-1919/

“Democracy in Steel” by John A Fitch

-from Survey of Jan 4, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=trRDAQAAMAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA453

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Homestead Strike Song · Pete Seeger