How often have court rooms served as undertaking parlors

for the aspirations of rebellious workers?

-Harrison George

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Sunday August 18, 1918

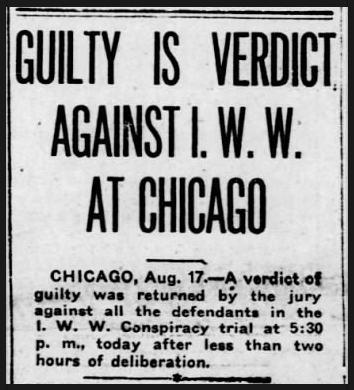

Chicago, Illinois – “Guilty Is Verdict Against I. W. W.”

At 5:30 p. m. on Saturday August 17, 1918, the Federal Trial of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World ended when the jury announced its verdict:

Guilty as charged in the indictment.

Asked for his response to the verdict, Fellow Worker Harrison George stated:

If America can stand it, I am sure the I. W. W. can.

Report from Harrison George:

NEBEKER concluded his speech at 10:33 a. m. [August 17th], and the crowded courtroom listened expectantly for Vanderveer to open the floodgates of oratory. Nebeker had used less than one hour of the two allotted to the prosecution, and his assistant, Claude R. Porter, was to finish the presentation of their side with a flag-waving broadside of denunciatory eloquence that was not only to sway the jury, but was intended to elect him governor of Iowa. For, thoughtful of his campaign in that state, he had on the previous day sent advance copies of his speech to a great many of his partisan papers in Iowa for release on that day, when he intended to talk himself into immortality.

Judge, oh, ye gods! how deeply he was wounded when Vanderveer forbore to orate, only rising to thank the jury for their patience during the long trial and asking their consideration for a “Christian judgment.” The spectators were nonplussed at such an unusual situation, while Porter, pale and stunned, sat voiceless, trying to grasp the fact that Vanderveer, by refusing to address the jury, had cut off further argument, and that he, Porter, was up against wiring those Iowa papers to kill his oration, already going into the presses.

Judge Landis, accepting the strange conclusion of the defense, leaned over the bench and informed the jury that he would adjourn until 2 p. m., and at that time would give his instructions. About twenty defendants who were out on bail, and nearly seventy who had been released on their own recognizance from time to time, were now taken, with the nine remaining in custody, to the “dining room,” No. 603, under guard. Here all were served with a noonday meal, and afterward mingled with their friends, wives and sweethearts, who gathered in the crucial hour. During this period there was noticed a heavy addition to the guard, a great number of police from the city mounted reserves filling the corridors.

At 2 p.m. the visitors were put out and the defendants, in pairs, marched through the corridors into the courtroom, No. 627. On the way through the corridors each defendant was stopped and searched, a somewhat ominous proceeding that resulted in nothing at all being found more dangerous than a newspaper.

It was 2:20 p. m. when Landis entered and the clerk called the roll of defendants. The “learned” judge then proceeded to read his instructions to the jury, which occupied an hour and thirty-five minutes, being concluded at 3:55 p.m. At 4 o’clock the jury filed out and then the defendants were again taken to Room 603 and again a meal was brought in. But there was no time to dine at leisure; the writer, in fact, being cut short in the middle of a gustatory process at 4:50 p. m., when the word came to return to court.

What had happened? What did it mean? Was the jury going to ask for further instructions? Was is possible that a verdict had been so quickly agreed upon? A hubbub of interrogation arose as the defendants dropped their knives and forks and again lined up in pairs for the march through the corridors. There was some delay in separating and seating the visitors, but by 5:15 p.m. the defendants were in their seats again.

Again the guarding force had been strengthened and a line of uniformed police surrounded the big room, while the entrance of the court was a solid mass of blue, brass buttons and gleaming stars. U. S. Marshal Bradley and a squad of deputies stood guard between the groups of defendants and the yet empty jury box. Immediately in front of the bench, at the prosecution’s table, sat Porter and an assistant. Nebeker was not present. A few feet further the long counsel table of the defense was vacant at the end toward the jury, usually occupied by Vanderveer, Christensen and Cleary.

At the other end, Haywood, J. A. McDonald, Ray Fanning and the writer sat, awaiting the necessary presence of defense counsel and whatever further was to come. Still the atmosphere of interrogation prevailed and the defendants whispered their conjectures to each other. “A verdict?” “Impossible!” “A blanket verdict?” “It may be.” “Where are our attorneys?” “Where is Vanderveer?” “He must not have expected so hasty a summons.”

The head bailiff of the court in charge of the jury came in hurriedly from the jury room and asked Fanning for Vanderveer’s telephone number. McDonald inquires: “Is there a verdict?” “Yes,” replies the bailiff, and rushes away. At this moment Defense Attorney Christensen enters and an attendant calls the jurors, who re-enter the box at 5:25 p. m. Their faces are void of expression, but there is one bad sign—they do not, or dare not, look toward the defendants, who eye them dubiously.

Down in Adams street, in front of the British recruiting station, to catch the homebound thousands, a band struck up, and the quaintest question enters my mind—“Is It ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,’ or is it ‘God Save the King’?”

Judge Landis enters and seats himself. His long and narrow face is the usual pallid mask, the bleached shroud of a conscience which lies within. He asks:

“Gentlemen of the Jury, have you arrived at a verdict in this case?”

There is no spoken reply, but the foreman of the jury, F. W. Brayton, of Morris, Illinois, rises and hands the bailiff a paper which is given over to Court Clerk Sullivan to read.

The clerk, reading in a strong, clear voice, begins: “We, the jurors in the case of the United States versus William D. Haywood et al., find the defendants, Carl Ahlteen, Olin B. Anderson, A. V. Azuara,” and goes on down the alphabetical roll—

“Charles Ashleigh.” One of the defendants whose guilt could be predicted solely on membership, as he was out of all touch with organization work during 1917–

“William D. Haywood.” It is plain now that a blanket verdict is coming, but what is it?

“Clyde Hough.” It flashes to mind that this boy, a lad against whom not a line of evidence, written or spoken, was offered, could not be found guilty of violating the Espionage Act, a law passed by Congress on June 15, 1917. It was incredible that this boy, Hough, who had been in jail every day since June 6, 1917, could be convicted of breaking the Espionage Act, shut off as he had been, by bars and locks since a week before the law was passed!

But what was the verdict? The time consumed in reading those one hundred names seems interminable.

“William Weyh.” The last name on the roster, and the funereal silence of the court was broken only by the dull, forgotten roar of the city. The clerk paused before the final line of the verdict, a verdict which had a parallel significance with Pilate’s submission to the mob, or the spurned petition of Brutus kneeling at the feet of Caesar, or the Dred Scott decision, a verdict to make or mar a nation as the abiding place of “Justice.”

It was 5:30 by the courtroom clock as that final line fell from the lips of the clerk:

“Guilty as charged in the indictment.”

Not a word of demonstration. The defendants sat quietly while the judge addressed the jury, thanking and dismissing them.

Here and there appeared an ironical smile on the face of a defendant. The countenance of Haywood, who was sitting beside me, was flushed, but there was no other trace of emotion. Christensen, phlegmatic as a rule, wore a look of agony on his round, red face. A reporter of the City News Bureau nervously clasped my arm. He seemed to ask apologetically, “What do you think of the verdict?” He was more distraught, to all appearances, than any defendant, and the writer laughingly reminded him that he, the reporter, was not going to jail. As to the Verdict:

“If America can stand it, I am sure the I. W. W. can.”

Christensen stepped forward to speak to the judge as Vanderveer entered, bowed a little by the weight of the dead hope whose shadow appeared in his eye. Immediately he was surrounded by “the boys,” the boys who ran up to shake his hand, to laugh at the whole world as they slapped him on the back and exclaimed, “You did your best. It was sure some scrap, anyhow !” . . .

David Karsner, reporter for the New York Call, a real writer and a real friend, ran in. A word with Haywood, and the boy collapsed as if wounded, his face ashen as he sank into a chair. He forced himself to rise as the boys passed out to shake hands in farewell, but his fingers had no grip and his voice was gone.

The prisoners passed out, two by two, through the doorway. In the corridor stood that brave and big-hearted little woman whose unnoticed work now seemed to have been in vain—Caroline Lowe, assistant attorney for the defense. The lawyer had gone and only the woman stood there. She nodded to us as we passed and smiled bravely through the tears she could not conceal.

Queer? Everyone was crying or nervous or distraught, except the prisoners. They seemed half gleeful, half nonchalant, in a sort of grim defiance.

A few minutes more and, in groups of ten, handcuffed in pairs, the prisoners were taken down in elevators to the ground floor and loaded into automobile patrols. The news spread and the streets were packed beyond the police lines, drawn to hold back the crowd. The prisoners laughed, passing remarks with one another.

Delayed while a way was made through the crowd, an auto load of prisoners sat at the curb. The boys inside the patrol, with the spirit which cannot die—the Spirit of the I. W. W., which sings in the face of defeat—struck up the song, “Hold the Fort.” Then, as the automobile turned into Dearborn street, on the road to the Cook County jail, they took up that historic song of revolt, “The Marseillaise.”

Doubtless the thoughtless thousands in the streets: wondered as the police auto sped clanging by what it all meant—those men on their way to prison exalted by song.

Oh, Liberty, can man resign thee,

Once having felt thy generous flame;

Can dungeon bolts and bars confine thee,

Or whips they noble spirit tame?[Newsclip added is from Reno Evening Gazette of August 17th.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

The I.W.W. Trial

Story of the Greatest Trial in Labor’s History

by one of the Defendants

-by Harrison George

—-with introduction by A. S. Embree.

IWW, Chicago, 1919

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100663067

Pages 203-208: The End of the Trial and the Verdict

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d01368761a;view=2up;seq=210

Note: First ad I can find for this book:

Butte Daily Bulletin -page 3

-Mar 5, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/176048912/

IMAGE

Chg IWW Trial, Guilty Verdict, Reno GzJr p1, Aug 17, 1918

https://www.newspapers.com/image/147174940/

See also:

Tag: Harrison George

https://weneverforget.org/tag/harrison-george/

Shall Freedom Die?

166 Union Men In Jail For Labor

by Harrison George

IWW Chicago, (Late 1917, still 166 defendants.)

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Shall_Freedom_Die%3F

Is Freedom Dead?

-by Harrison George

IWW Chicago, (Intro by HG, Jan 20, 1918, pub’d before trial.)

https://www.sos.wa.gov/legacy/images/publications/sl_georgeisfreedomdead/sl_georgeisfreedomdead.pdf

The Red Dawn

The Bolsheviki and the IWW

by Harrison George

IWW, (Early 1918)

https://archive.org/stream/TheRedDawnTheBolshevikiAndTheI.w.w/reddawn#page/n0/mode/1up

Note: the following ad on page 1 places publication before April 1918; within text, George describes events of November 1917.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~