———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday February 10, 1920

Youngstown, Ohio – Mary Heaton Vorse Observes the Picket Line

From The Fresno Morning Republican of February 8, 1920:

Mary Heaton Vorse can see-and tell what she sees. Her study of a Slovak steel striker is mighty well done, entitled “Behind the Picket Line,” in the Outlook for January 21.

[Emphasis added.]

From The Outlook of January 21, 1920:

BEHIND THE PICKET LINE

THE STORY OF A SLOVAK STEEL STRIKER

-HOW HE LIVES AND THINKSBY MARY HEATON VORSE

[Part I of II.]

[Note: see Introduction by “The Editors” below.]

When I got out of the street car, he detached himself from the darkness and murmured:“Ma’am, I come to meet you.”

It was not yet five, and black as midnight, except as the fiery salvos of the newly started blast-furnace of the Ohio plant shattered the night with glory. No need to ask how he knew me. Women do not usually get off the cars at five in the morning at this point.

On my way to the picket line I had been alone, with the exception of two uneasy-looking scabs. I didn’t look at them. I didn’t like to. The right of the individual workman to work when and how he wished seemed a rather hypocritical theory to me at that moment. It seemed about as tenable as the right of the individual citizen to desert to the enemy in war time.

For weeks I had been immersed in the strike. I had gone merely as an observer, rather skeptically even, and the thundering immensity of the thing had caught me up.

The people—that is to say, the public, those not directly interested—look on strikes as unchancy occurrences, violent manifestations which interfere with the ordered flow of existence. Something that wouldn’t happen at all if it were not for “outside agitators”—that most slippery of all explanations.

What had happened to me was that I had looked at the strike close to, and it had resolved itself into the lives of human beings—thousands of human beings thinking the same thing, thousands of human beings hoping the same thing, thousands and thousands of human beings hoping and willing the same thing, with the terrible patience of the simple. It is a dramatic thing when thousands of men all through the country, men in eight different States, men in fifty different towns and communities, all decide to stay home, all decide to do nothing, because they wish to alter certain conditions.

Men who never saw each other, men who never will see each other, many men who couldn’t understand each other if they were to meet, all doing the same thing, sitting quiet—abstaining violently from action, all bound together by the same thought—the men in all these widely sundered communities thinking together about the same thing. That is one of the things a strike resolves itself into when you look at it close to.

All this thought focuses on the picket line, where, before the mill gates, goes on a terrible and silent contest of wills. Youngstown had been closed down tight. Youngstown had been dark as a pocket. For days and for weeks no plume of smoke had floated over any chimney. For the first time in years there was no crimson flare in the sky by night.

Then the Ohio works had opened up—the people said with Negro strike-breakers. All the Sunday before the strikers had been poised fearfully, as though upon the brink of disaster. Rumors flew through the town. Everything was going to open, every one was going back to work. All the sacrifice Was in vain—every one was going back and the strike would be lost.

I had gone out to see the disaster. We walked through the darkened streets, past a group of policemen on the corner, with whom we exchanged “good-mornings.” Up the side streets stood groups of men. A man with tools came hurrying along.

“W’ere you going, boy?” my guide challenged.

“Going to work up to town—going to work up to Denis’s—I ain’t scabbin’. You didn’t think I was?” He was young and eager; he couldn’t bear the implication that he was a deserter.

Another man scuttled through the dark, head down, tool-box held tight.

“W’ere you going, boy?” the challenge came again. There was no menace in his deep voice, no note of bullying, only a sorrowful and accusing gravity. “W’y you going to work, boy? don’t you know we’re on strike?” Without stopping, the man pelted past us down the street, whose darkness was now violently torn asunder by the sudden splendid fury of the blast. The buildings, the high chimneys and walls and bridges, the houses and the knots of men, were all etched black against the magnificent violence of flame.

The picket line thickened. The men moved up and down sluggishly, just enough to conform with the law, which advises picketers to keep moving. A patrol wagon came at and some policemen got out near the gate of the mills. Three big wagons thundered over the bridge leading to the mill gate—provisions for the scabs.

And now a sparse trickle of men bean coming over the bridge out of the mill. They crossed another group coming in. From the point of view of those quiet watching men the others were traitors, deserters, men of the spawn of Judas. The pickets were quiet and watchful. No one spoke. They were like a slow, anxious, drifting stream, while the men coming and going from work moved swiftly, head down, shoulders hunched——apprehensive to get out of sight of that watchful line with its terrible and accusing quiet.

Day came creeping on us; we could now see one another. A light primrose stained the sky, which seemed far off and remote. Dawn touched the men’s faces; they looked cold and tired, they looked anxious and worn. The whistle gave tongue; more men hurried out of the mill, more men scuttled in. The patrol wagon came up, the police drove off in it.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

Note: The article was introduced by “The Editors” who clearly should try working 12 hour per day, 7 days per week, for uncertain and arbitrary wages, where death on the jobs is a weekly-if not daily-occurrence. Then we could ask them if the Great Steel Strike was due only to some “misunderstanding.”

Most strikes—in America, at least—are not based on hard-hearted selfishness. Their real source is misunderstanding. As misunderstandings between friends often lead to the breaking off of friendly relations, to recriminations, and sometimes to lifelong quarrels, so it is with labor and capital. We print this vivid story because it so clearly shows that the conflict between wage-workers and employers is, after all, a conflict in which the highest human aspirations are engaged. The head of a great steel works whose property is destroyed and whose life even is threatened in a strike feels that he is fighting for the future security of his family. The worker, like the Slovak of Mrs. Vorse’s story, who, in some way that he does not quite understand, is separated most of the time from his home, fells that he is fighting for the future of his family. Is not this the real problem in the present industrial situation—to find some way by which the two sides may understand each other?—THE EDITORS.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

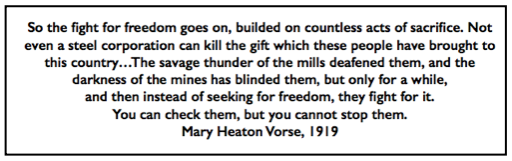

Quote MHV Immigrants Fight for Freedom, Quarry Jr p2, Nov 1, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/405049859

The Fresno Morning Republican

(Fresno, California)

-Feb 8, 1920

https://www.newspapers.com/image/607287537/

The Outlook, Volume 124

(New York, New York)

-Jan-Apr 1920

The Outlook Company, 1920

https://books.google.com/books?id=wds6AQAAMAAJ

Page 90: Jan 21, 1920

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=wds6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA90

Page 107: Article by Mary Heaton Vorse

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=wds6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA107

Re Conditions in the Steel Mills:

Men and Steel

-by Mary Heaton Vorse

New York, Boni and Liveright, 1920

https://archive.org/details/mensteel00vors/page/n5

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

-by William Z. Foster

B. W. Huebsch, Incorporated, 1920

https://books.google.com/books?id=Hbt-AAAAMAAJ

IMAGE

MHV, NYS p37, Dec 1, 1918

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030431/1918-12-01/ed-1/seq-37/

The Outlook, LF Abbott, President, p90, Jan 21, 1920

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=wds6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA90

See also:

Tag: Great Steel Strike of 1919

https://weneverforget.org/tag/great-steel-strike-of-1919/

Tag: Mary Heaton Vorse

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mary-heaton-vorse/

Lawrence Fraser Abbott

Note: I searched but could not find the names of “The Editors,”

however, Abbott was, on Jan 21, 1920, President of the Publishing Company.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Fraser_Abbott

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Homestead Strike Song