—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Monday December 21, 1914

Fellow Worker Joe Hill Writes to Editor of Solidarity from Salt Lake County Jail

From Solidarity of December 19, 1914:

CHEERFUL NOTE FROM JOE HILL

—————Salt Lake County Jail, Nov. 29

Editor Solidarity:

I see in the “Sol” that you are going to issue another edition of the Song Book, and I made a few changes and corrections which I think should improve the book a little, which I am enclosing herewith.

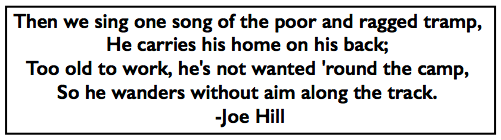

Now, I am well aware of the fact there are lots of prominent rebels who argued that satire and songs are out of place in a labor organization and I will admit that songs are not necessary to a movement. But I think that our little Song Book is doing good work for the cause; and whenever I “get the hunch” I intend to make some more foolish songs, although I realize that the class struggle is a very serious thing.

A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over; and I maintain that if a person can put a few cold, common sense facts into a song, and dress them (the facts) up in a cloak of humor to take the dryness off of them, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial on economic science.

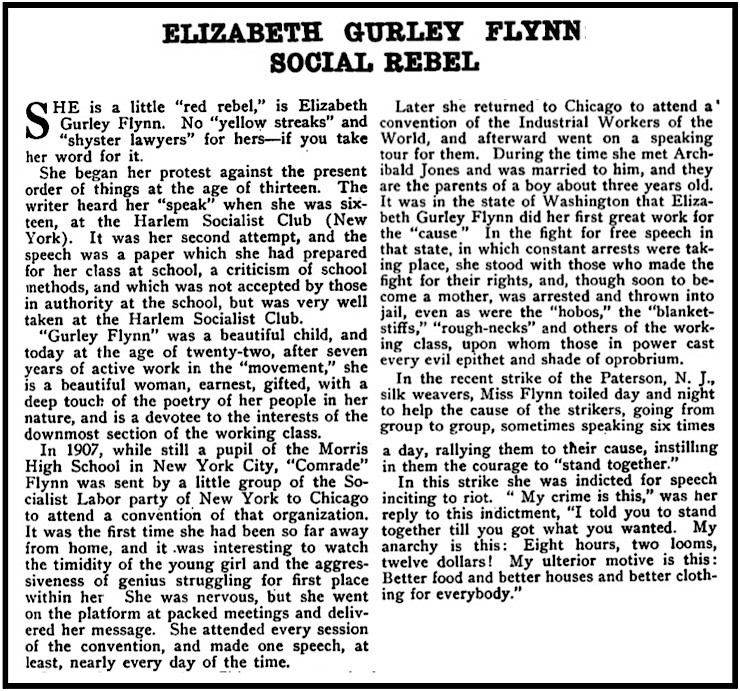

There is one thing that is necessary in order to hold the old members and to get the would-be members interested in the class struggle and that is entertainment. The rebels of Sweden have realized that fact, and they have their blowouts regularly every week. And on account of that they have succeeded in organizing the female workers more extensively than any other nation in the world. The female workers are sadly neglected in the United States, especially on the West coast, and consequently we have created a kind of one-legged, freakish animal of a union, and our dances and blowouts are kind of stale and unnatural on account of being too much of a “buck” affair; they are too lacking the life and inspiration which the woman alone can produce.

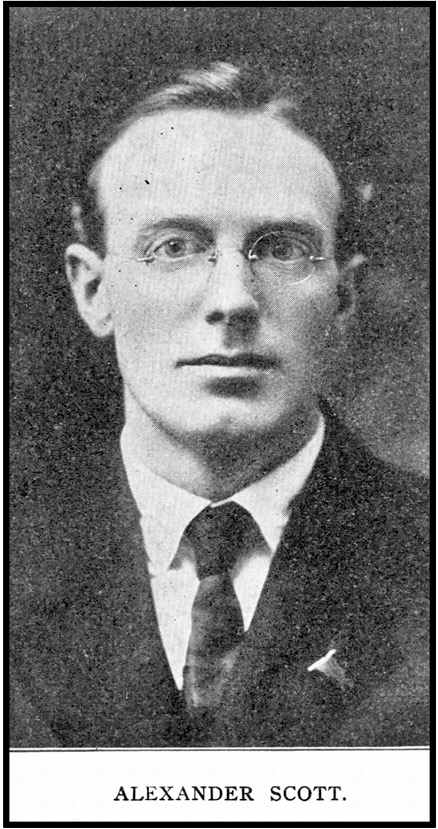

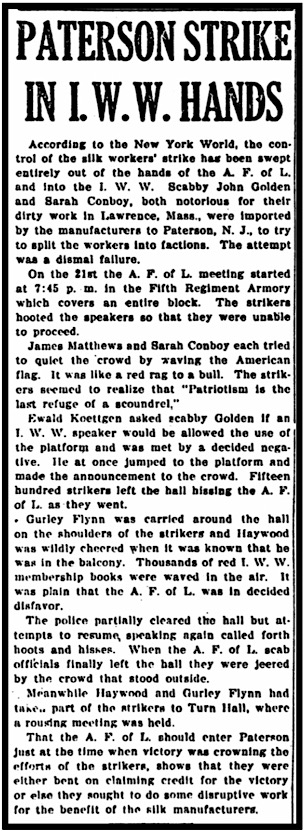

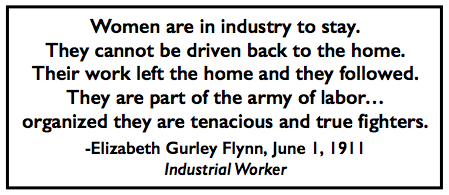

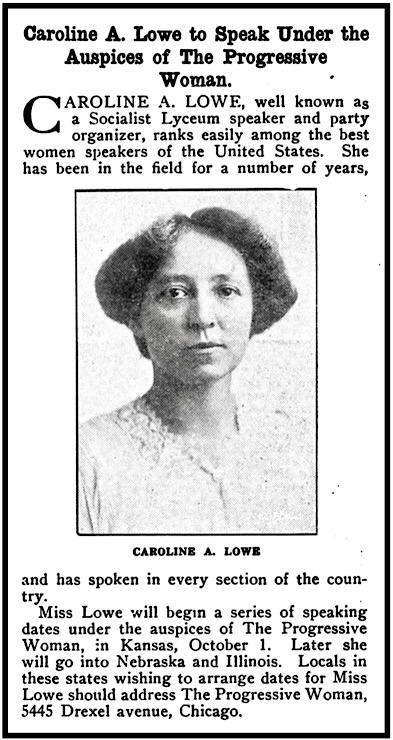

The idea is to establish a kind of social feeling of good fellowship between the male and female workers, that would give them a little foretaste of our future society and make them more interested in the class struggle and the overthrow of the old system of corruption. I think it would be a very good idea to use our female organizers, Gurley Flynn, for instance exclusively for the building up of a strong organization among the female workers. They are more exploited than the men, and John Bull is willing to testify to the fact that they are not lacking in the militant and revolutionary spirit.

By following the example of our Swedish fellow workers, and paying a little more attention to entertainment with original song and original stunts and pictures, we shall succeed in attracting and interesting more of the young blood, both male and female, in the One Big Union.

Yours for a change,

Joe Hill.Address Jos. Hillstrom, Co. Jail, Salt Lake City, Utah

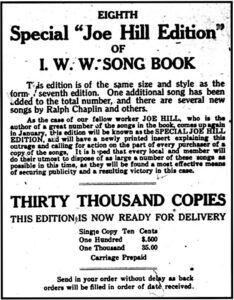

(We are more than pleased to offer these suggestions from Fellow Worker Hill to our readers, and believe they should be given thorough consideration by all active I. W. W. men and women. We are sorry that Hill’s corrections and changes for some of his songs arrived too late for the Eighth edition, which was already on the press when his letter came. Will keep them on file for a later edition.-Editor Solidarity.)

[Emphasis added.]

—————

————— —–

—– —–

—–

—————

—————

—————-

—————-