—————

—————

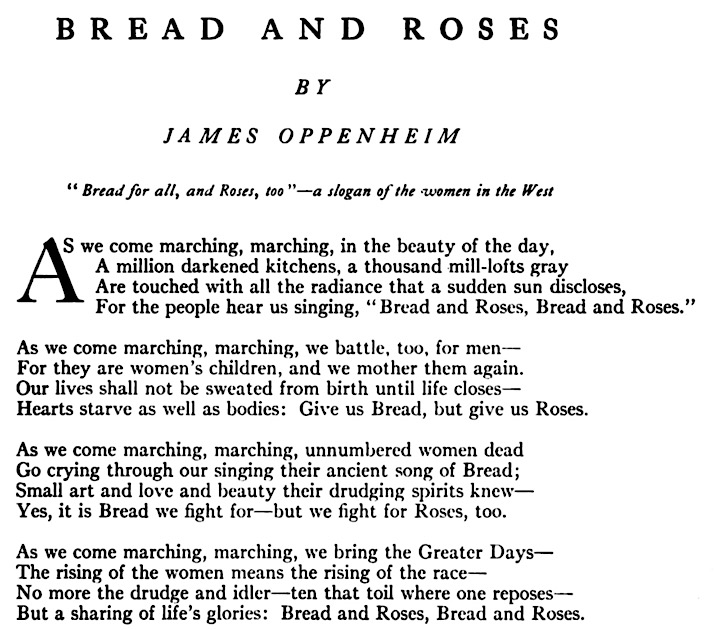

From The American Magazine of December 1911:

Judy Collins – Bread and Roses – Judy Collins

Lyrics by James Oppenheim

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

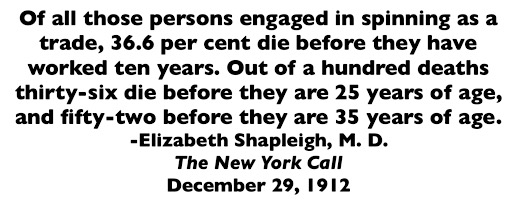

Quote Elizabeth Shapleigh MD, Death Rate of Spinners Lawrence, NY Call p13, Dec 29, 1912

https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/fake/fake.pdf

The American Magazine

(New York, New York)

-Dec 1911, p214

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012106988&view=2up&seq=230

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

“Bread and Roses”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bread_and_Roses

The American Magazine

(New York, New York)

-Sept 1911, p619

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.32000000494361&view=2up&seq=629

Note: article begins on page 611

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.32000000494361&view=page&seq=621

Getting Out the Vote

An Account Of a Week’s Automobile

Campaign by Women Suffragists

by Helen Todd[…..]

Late as it was [after the last meeting of the tour], the old bed-ridden mother was awake and called softly for me to come in and and tell her about the meetin’. “I knew it would be a fine meetin’,” she said. “I had my bed turned ’round to the window. I seen the wagons coming in from out of town since morning. I knew you’d be leaving for Chicago early, and I just thought I would wait up for you so’s I could hear all about it and tell Lucy. You see,” she explained, “Daughter Lucy and the hired girl couldn’t both go and leave me alone, since I have had my stroke. Lucy, she was born and brought up to woman’s rights, bein’ my daughter; but our hired girl’s new in our family and real ignorant about it. So Lucy she felt it was her duty to send our girl to get converted, and stay to home herself. I‘m a believer, she said, “and Maggie ain’t. But Lucy she felt terrible put out about it though she didn’t let on to me of course, and I made up my mind I’d ask you to just say over what you said so’s I could tell it to her. I had hoped,” she added, “that I’d last to see the day when women would vote in Illinois, but if Susan B. Anthony can die without seein’ it, I guess I can. It’s a comfort to see you young women keepin’ up the same fight that we started back East when we was young and spry. It makes us feel as if we hadn’t educated you for nothing, for we did educate you. ‘What, educate shes!’ the men said when we wanted the girls to go to school. What’s the use spendin’ money on educatin’ shes?’ Well I guess we’ve showed them what the use was. I’ve seen that done anyhow.”

We had breakfast next morning at the usual hour of 6 A.M., in the old farm kitchen with its big black cook stove, its centerpiece of the lady slipper flowers on the table, and its back door opening on a yard full of hollyhocks. Maggie ate with us. “If you want to know what I liked the best of all in the whole meetin’,” she said, “it was that about the women votin’ so’s everybody would have bread and flowers too.” Now, that’s what mother took a fancy to,” said my hostess. “Mother’s close on to ninety-two come next birthday, and I thought I would make her a birthday present of a sofa pillow with votes for women embroidered on it, but she took such a fancy to this ‘Bread and Flowers’ automobile campaign idea that I’m going to ask you to do me the favor to step into Marshall Field’s and get that motto stamped on a pillow and send it to me….

The flowers they gave me when I left have faded; and the paper of prize hollyhock seeds bestowed upon me to plant in my backyard have never been planted, as my only back yard is the fire escape. But my heart is still warm with the memory of friendship of these down-State women.

I saw that Mother Jones’ pillow was sent back East to her [Mother of Lucy, see above] with the inscription, “Bread for all, and Roses too.” No words can better express the soul of the woman’s movement, lying back of the practical cry of “Votes for Women,” better than this sentence which had captured the attention of both Mother Jones and the hired girl, “Bread for all, and Roses too.” Not at once; but woman is the mothering element in the world and her vote will go toward helping forward the time when life’s Bread, which is home, shelter and security, and the Roses of life, music, education, nature and books, shall be the heritage of every child that is born in the country, in the government of which she has a voice.

There will be no prisons, no scaffolds, no children in factories, no girls driven on the street to earn their bread, in the day when there shall be “Bread for all, and Roses too.”

[Emphasis added.]

From The New York Call p13 of Sunday December 29, 1912:

(See Blog Post by Peter G. Doyle, 2019; scroll down.)

https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/fake/fake.pdf

Occupational Diseases in the Textile Industry

By Elizabeth Shapleigh, M.D.It is clearly pointed out by all authorities on industrial disease that the mortality is high in all dusty trades, including the textile industry. Nevertheless, before measures of amelioration can be taken, there must be secured detailed, accurate information of the conditions under which the work is carried on and the degree of ill health among the workers. With this end in view, I will describe some of the insanitary conditions in the Lawrence textile mills and their effect on the workers.

The city of Lawrence, Mass., outranks every other city in the Union in the manufacture of woolen and worsted goods. Out of a total population of 85,892, approximately one-half of the men and women over 14 years of age are employed in this one industry. This offers an exceptional opportunity to investigate industrial disease.

Data have been obtained by personal observation in the mills, from various public records and reports, and eminent medical authorities. The vital statistics tabulated in this paper are taken from the records of the city of Lawrence, Mass., for the years 1903–1911 inclusive.

The essential elements in the sanitary arrangements peculiar to textile mills are a proper regulation of the ventilation, the temperature and the humidity, besides a proper disposal of the fine organic dust generated during the process of cloth-making. When neglected, as they now are, these four factors combine to produce unhygienic surroundings, and markedly affect the health of the worker.

Let us consider first the high degree of humidity maintained in the weaving room. A certain amount of moisture is necessary in order to soften the sizing on the thread so that it may be more easily manipulated in the process of weaving. This sizing, by the way, adds to the weight and so is wrong from a moral point of view. Besides, the flocculent dust which it produces is inhaled and, therefore, harmful to the operative. To obtain the required humidity, steam is artificially introduced at regular intervals by steam jets near the ceiling. At times it is so excessive as to cause perceptible dampening of the clothing of the worker.

Added to this is the high temperature, kept at about 84 F. in winter and frequently rising to 130 F. and over on a hot summer day. It is easy to understand how, with garments saturated with perspiration and moisture, the workers upon leaving such an atmosphere and proceeding home on a cold winter evening become thorouhly chilled. This causes them to be especially susceptible to bronchitis, pulmonary complaints, and to rheumatism. Moreover, the hot, moist air is enervating and unfits one to bear fatigue. It is difficult to estimate the full effect, for neurasthenia, the bane of the overworked and underfed, does not leave a definite trace on the mortality records.

Furthermore, the ventilation is insufficient. A draft of air causes the thread to break. Consequently, the windows are rarely opened except in summer. From good authority we learn that the room is never ventilated after work hours.

All that has been said about heat and moisture in the weaving-room applies equally to the dye-house. There the moisture is so great that it condenses on the walls, floor, and even on the hair of the dyers. The constantly wet cement floors cause the bare or shoe-clad feet of the dyer to be always wet and cold, a predisposing cause of respiratory disease and rheumatism. The inhalation of the arsenical fumes from the aniline dye likewise has an injurious effect.

The fine particles of fiber thrown off in the process of carding and spinning are suspended in the air like a thick misty cloud, which obscures the vision. These particles settle on the hair and garments of the operatives. They fall on their face, cling to the eyebrows and fringe the nostrils, irritating the delicate mucus lining. In the carding-room this dust is excessive. It hangs on the machinery and drops from it in large masses, covering the floor.

This fine organic dust irritates the delicate membranes lining the nose, throat, larynx, and bronchial tubes. In the smaller bronchi and air cells of the lungs the dust induces a low form of inflammation, which ends in the transformation of the spongy substance of the lung into hard unyielding fibrous tissues quite unfitted for the purpose of respiration. This fibrotic lung disease is termed pneumokomosis. On microscopic examination of the sputum, fibers of the cotton or wool may be found.

The rate of mortality from pneumonia among weavers is 17.9 per cent, as compared with 12.6 per cent among spinners. Among dyers it is higher than that shown in any other room (18.7 per cent). Mortaility from tuberculosis is greater among spinners and combers. It is 27.2 per cent in the first and 33 1-3 per cent in the latter, as compared with 18.4 per cent among weavers. The death rate from tuberculosis is also high among dyers. Another noteworthy fact is the high mortality from respiratory diseases, including pulmonary tuberculosis. According to the statistics it is 46.9 per cent among dyers and 53.3 per cent among combers.

A study of the mortality from tuberculosis, pneumonia and from total causes of death of spinners, at specified age periods, discloses that 50 per cent of the deaths of spinners from tuberculosis occurs before the 25th year, and 75 per cent before the 35th year. Deaths from pneumonia occur at a much later age. Only 20 per cent occur before the 35th year and 40 per cent between the 56th and 65th years.

Of all those persons engaged in spinning as a trade, 36.6 per cent die before they have worked ten years. Out of a hundred deaths thirty-six die before they are 25 years of age, and fifty-two before they are 35 years of age. That is, over one-third die just as they attain maturity, and over one-half as they reach the most productive years. It is very rare that a spinner lives to be 70 years of age.

Among the various occupations carried on in the City of Lawrence, Mass., the one sowing the greatest mortality from tuberculosis is the textile industry; 27.1 per cent of all operatives die from infection by bacillus of tuberculosis. There have been 1,010 recorded deaths of textile operatives in the city during the last nine years (1903–1911) and 274 of them have been due to tuberculosis. Whereas from the twenty-one recorded deaths of manufacturers there has not been a single death from that disease.

Mortality from tuberculosis in the professional class was 9.7 per cent, or only one-third of that among operatives. The farmers show a consumptive morality of four-fifths of 1 per cent, and the day laborer 12.8 per cent, while the skilled trades range between this low mortality on the one hand, and the high mortality among operatives.

Mortality from pneumonia is high among all classes of operatives, but rates the highest among the dyers (18.8 per cent). The death rate from the various forms of respiratory trouble show the lowest record among farmers, 2.6 per cent, and the highest among textile operatives, 41 per cent. Death from respiratory trouble occurs only one-third as often among textile manufacturers as among textile mill employes.

Philanthropists and social workers lay much stress on housing conditions— poor ventilation, dark rooms, crowded tenements—as causes of tuberculosis among the poorer portion of the working class. In comparing the mortality statistics of the unskilled laborer with that of the operatives, we find the longevity much greater. These two classes of workmen live in similar home environment, in the same poverty-stricken condition, yet only 12.8 per cent died from tuberculosis, and only 29.6 per cent from respiratory trouble. The mortality from consumption among day laborers, then, is only one-half that among mill operatives. Furthermore, the death rate from respiratory trouble is only 29.6 per cent, as compared with 41 per cent among operatives in general, and 53.3 per cent among the combers. It would be interesting and instructive to collect additional data along this line.

A study of the figures will show the average longevity in the most important occupations in the City of Lawrence, according to the mortality records of that city for the years 1903–1911, inclusive. Lawyers and clergymen head the list with an average length of life of 65.4 years. Manufacturers come next with a longevity of life of 58.5 years, and farmer with 57 years. Operatives have the shortest life-span. From the mortality record of 1,010 operatives, the average length of life was found to be 39.6 years. The average longevity of the spinners is three and two-fifths years less, or 36 years. On an average, a spinner’s life is twenty-two and one-half years shorter than that of his employer, the manufacturer.

Another significant fact is that the longevity of the laborer is considerably greater than that of the textile operative. From 373 deaths among laborers the average length of life was 47.6 years, while that of the operative is eight years less, and of the spinner eleven and three-fifths years less. Bear in mind that the former reference was made to the fact that although living in practically the same home environment the mortality from tuberculosis and respiratory disease was much less than that among textile operatives. The men and women in these various occupations lived and worked in the same city, subject to the same climate and the same atmospheric variations.

The report on the strike of the textile workers in Lawrence, Mass., in 1912, which was prepared under the direction of Charles P. Neill, Commissioner of Labor, shows that approximately 11.5 per cent of the total mill employes are under 18 years of age. Among the foreign population it is the custom for a boy or a girl to go to work in the mill as soon as possible after the 14th birthday. Many of these, when beginning work, suffer from a malaise known as “mill fever,” the symptoms of which are nausea, vomiting, headache, and rise of temperature. Usually the indisposition lasts only two or three days. It is attributed to the inhalation of dust, the stifling atmosphere and the disagreeable odor of the oil.

From the mortality statistics we learn that a considerable number of these young boys and girls die within the first two or three years after beginning work. With very few exceptions, death is due to tuberculosis, pneumonia, or typhoid fever.

Data with regard to the consumptive mortality per 1,000 operatives could not be obtained, because of the inaccurate and incomplete mortality record of the city. For instance, a large number of women work in the mills, either before or after marriage, and contract tuberculosis and die. Because they are married their occupation is recorded as “at home” or “housewife.” The significant fact that they have worked in the mill is lost and it becomes impossible to trace the true cause of their contracting the disease. Again, a number of young men and women who have been out of the mill, ill with tuberculosis for several month or years, are recorded as “at home.” Here again their occupation is not recorded and the reason for their contracting consumption may not be attributed to the real cause. Again, in statistics of various trades and professions, the word “retired” is often used instead of stating the former occupation as well. This simple addition would facilitate matters, and permit of greater accuracy.

The high mortality in the textile industry can largely be averted by the introduction of a few simple devices. A careful and thorough regulation of the ventilation, humidity, and temperature must be insisted upon. It is a known fact that thought for the welfare of the worker is not considered in the regulation of these conditions. Temperature is maintained much higher, necessitating a greater degree of humidity in the weaving-rooms of this country than is permitted abroad. England and Germany have stringent laws requiring modern appliances about the machines, whereby the dust is carried off from the point of production by ventilating flues, hoods, shafts, fans, etc.

Introduction of these simple devices would make an appreciable difference in the mortality from tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases. It is hoped that in the near future the textile operatives in the United States may work under the same hygienic conditions as now exist abroad.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bread and Roses: The Lawrence Textile Strike

LaborEd Minnesota