Pray for the dead and

fight like hell for the living.

-Mother Jones

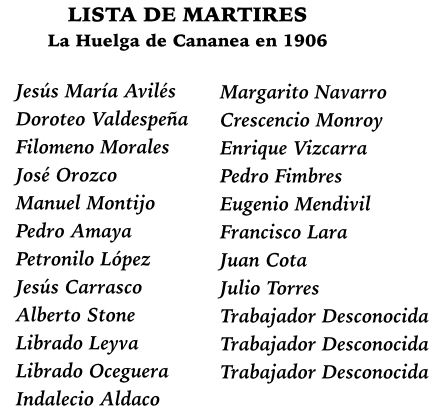

Martyrs of the Cananea Strike of 1906:

After much searching, I came upon the above list of martyrs’ names at the Chronicles of Cananea website. An explanation for the list is given in Spanish:

Lista de Mártires de la Huelga publicada en el Semanario 1906En el órgano de difusión de la Sección 65 del Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores Mineros, Metalúrgicos, Siderúrgicos y Similares de la República Mexicana (SNTMMSSRM), el Semanario 1906 con fecha 1 de junio de 1964, en un homenaje que se les hace a los Mártires de la Huelga, publica una relación de 23 mártires, relación que es prácticamente igual a la de Almada [*], con la diferencia que agrega a Jesús María Avilés e incorpora a Librado Oceguera y a Librado Leyva como personas diferentes, además de ponerle apellido a Margarito N. (Navarro) y agrega a los calcinados.

* Almada, Francisco R. Dictionary of History, Geography and Biography Sonorenses. Fourth edition. Sonora State Government, 2009.

Translated by Google:

List of Martyrs of the Strike published in the Semanario 1906

In the disseminator of Section 65 of the National Union of Mine, Metal, Steel and Allied Workers of the Mexican Republic (SNTMMSSRM), the Semanario 1906 dated June 1, 1964, in a tribute that makes them the Martyrs Strike, published a list of 23 martyrs, a relationship that is practically equal to that of Almada, with the difference that adds Jesus Maria Aviles and incorporates Librado Oceguera and Librado Leyva as different people besides name put Margarito N. (Navarro) and adds to the charred.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

“De Muertos, Heridos y Presos: La Huelga de Cananea en 1906”

-by Gustavo A. Moreno Martínez, domingo, 31 de mayo de 2015

http://cronicasdecananea.blogspot.com/2015/05/de-muertos-heridos-y-presos-la-huelga.html

The Cananea Strike of June 1906

From Barbarous Mexico by John Kenneth Turner

—–

The Cananea strike, occurring as it did, very close to the border line of the United States, is perhaps the one Mexican strike of which Americans generally have heard. Not having been a witness, nor even having ever been upon the ground, I cannot speak with personal authority, and yet I have talked with so many persons who were in one way or another connected with the affair, several of whom were in the very thick of the flying bullets, that I cannot but believe that I have a fairly clear idea of what occurred.

Cananea is a copper city of Sonora, situated several score of miles from the Arizona border. It was established by W. C. Greene, who secured several million acres along the border from the Mexican government at little or no cost, and who succeeded in forming such intimate relations with Ramon Corral and other high Mexican officials that the municipal government established upon his property was entirely under his control, while the government of the Mexican town close beside it was exceedingly friendly to him and practically under his orders. The American consul at Cananea, a man named Galbraith, was also an employe of Greene, so that both the Mexican and United States governments, as far as Cananea and its vicinity was concerned, were—W. C. Greene.

Greene, having since fallen into disrepute with the powers that be in Mexico, has lost most of his holdings and the Greene-Cananea Copper Company is now the property of the Cole-Ryan mining combination, one of the parties in the Morgan-Guggenheim copper merger.

In the copper mines of Cananea were employed six thousand Mexican miners and about six hundred American miners. Greene paid the Mexican miners just half as much as he paid the American miners, not because they performed only half as much labor, but because he was able to secure them for that price. The Mexicans were getting big pay, for Mexicans—three pesos a day, most of them. But naturally they were dissatisfied and formed an organization for the purpose of forcing a better bargain out of Greene.

As to what precipitated the strike there is some dispute. Some say that it was due to an announcement by a mine boss that the company had decided to supersede the system of wage labor with the system of contract labor. Others say it was precipitated by Greene’s telegraphing to Diaz for troops, following a demand of the miners for five pesos a day.

But whatever the immediate cause, the walkout was started by a night shift May 31, 1906. The strikers marched about the company’s property, calling out the men in the different departments. They met with success at all points, and trouble began only at the last place of call, the company lumber yard, where the parade arrived early in the forenoon. Here the manager, a man named Metcalfe, drenched the front ranks with water from a large hose. The strikers replied with stones, and Metcalfe and his brother came back with rifles. Some strikers fell, and in the ensuing battle the two Metcalfes were killed.

During the parade, the head of the Greene detective squad, a man named Rowan, handed out rifles and ammunition to the heads of departments of the company, and as soon as the fight started at the lumber yard the company detective force embarked in automobiles and drove about town, shooting right and left. The miners, unarmed, dispersed, but they were shot as they ran. One of the leaders, applying to the chief of police for arms with which the miners might protect them selves, was terribly beaten by the latter, who put his entire force at the service of the company. During the first few hours after the trouble some of the Greene men were put in jail, but very soon they were released and hundreds of the miners were locked up. Finding that no justice was to be given them, the bulk of the miners retired to a point on the company’s property, where they barricaded themselves and, with what weapons they could secure, defied the Greene police.

From Greene’s telegraph office were sent out reports that the Mexicans had started a race war and were massacring the Americans of Cananea, including the women and children. Consul Galbraith sent out such inflammatory stories to Washington that there was a flurry in our War Department; these stories were so misleading that Galbraith was removed as soon as the real facts became known.

The agent of the Department of Fomento of Mexico, on the other hand, reported the facts as they were, and through the influence of the company he was discharged at once.

Colonel Greene hurried away on his private car to Arizona, where he called for volunteers to go to Cananea and save the American women and children, offering one hundred dollars for each volunteer, whether he fought or not. Which action was wholly without valid excuse, since the strikers not only never assumed the aggressive in the violent acts of Cananea, but the affair was also in no sense an anti-foreign demonstration. It was a labor strike, pure and simple, a strike in which the one demand was for a raise of wages to five pesos a day.

While the false tales sent out from Greene’s town were furnishing a sensation for the United States, Greene’s Pinkertons were sent about the streets for an other shoot-up of the Mexicans. Americans had been warned to stay indoors, in order that the assassins might take pot shots at anything in sight, which they did. The total list of killed by the Greene men—which was published at the time—was twenty-seven, among whom were several who were not miners at all. Among these, it is said, was a boy of six and an aged man over ninety, who was tending a cow when the bullet struck him.

By grossly misrepresenting the situation, Greene succeeded in getting a force of three hundred Americans, rangers, miners, stockmen, cowboys and others, together in Bisbee, Douglas and other towns. Governor Yzabal of Sonora, playing directly into the hands of Greene at every point, met this force of men at Naco and led them across the line. The crossing was disputed by the Mexican customs official, who swore that the invaders might pass only over his dead body. With leveled rifle this man faced the governor of his state and the three hundred foreigners, and refused to yield until Yzabal showed an order signed by General Diaz permitting the invasion.

Thus three hundred American citizens, some of them government employes, on June 2, 1906, violated the laws of the United States, the same laws that Magon and his friends are accused of merely conspiring to violate, and yet not one of them, not even Greene, the man who knew the situation and was extremely culpable, was ever prosecuted. Moreover, Ranger Captain Rhynning, who accepted an appointment of Governor Yzabal to command this force of Americans, instead of being deposed from his position, was afterwards promoted. At this writing he holds the fat job of warden of the territorial penitentiary at Florence, Arizona.

The rank and file of those three hundred men were hardly to be blamed for their act, for Greene completely fooled them. They thought they were invading Mexico to save some American women and children. When they arrived in Cananea on the evening of the second day, they discovered that they had been tricked, and the following day they returned without having taken part in the massacres of these early days of June.

But with the Mexican soldiers and rurale forces which poured into Cananea that same night it was different. They were under the orders of Yzabal, Greene and Corral, and they killed, as they were told to do. There was a company of cavalry under Colonel Barron. There were one thousand infantrymen under General Luis Torres, who hurried all the way from the Yaqui river to serve the purposes of Greene. There were some two hundred rurales. There were the Greene private detectives. There was a company of the acordada.

And all of them took part in the killing. Miners were taken from the jail and hanged. Miners were taken to the cemetery, made to dig their own graves and were shot. Several hundred of them were marched away to Hermosillo, where they were impressed into the Mexican army. Others were sent away to the penal colony on the islands of Tres Marias. Finally, others were sentenced to long terms in prison. When Torres’ army arrived, the strikers who had barricaded themselves in the hills surrendered without any attempt at resistance. First, however, there was a parley, in which the leaders were assured that they would not be shot. But in spite of the fact that they persuaded the strikers not to resist the authorities, Manuel M. Dieguez, Esteban E. Calderon and Manuel Ibarre, the members of the executive board of the union, were sentenced to four years in prison, where they remain to this day—unless they are dead.

Among those who were jailed and ordered shot was L. Gutierrez De Lara, who had committed no crime except to address a meeting of the miners. The order for the shooting of De Lara, as well as for the others, came direct from Mexico City on representations from Governor Yzabal. De Lara had influential friends in Mexico, and these, getting word through the friendship of the telegraph operator and the postmaster of Cananea, succeeded in securing De Lara’s reprieve.

The end of the whole affair was that the strikers, literally hacked to pieces by the murderous violence of the government, were unable to rally their forces. The strike was broken, and in time the surviving miners went back to work on more unsatisfactory conditions than before.

Such is the fate the Czar of Mexico metes out to workingmen who dare demand a larger share of the products of their labor in his country. One thing more remains to be said. Colonel Greene refused to grant the demand of the miners for more wages, and he claimed to have a good excuse for it.

“President Diaz,” said Greene, “has ordered me not to raise wages, and I dare not disobey him.”

It is an excuse that is being offered by employers of labor all over Mexico. Doubtless President Diaz did issue some such an order, and employers of Mexican labor, Americans with the rest of them, are glad to take advantage of it. American capitalists support Diaz with a great deal more unanimity than they support Taft. American capitalists support Diaz because they are looking to Diaz to keep Mexican labor always cheap. And they are looking to Mexican cheap labor to help them break the back of organized labor in the United States, both by transferring a part of their capital to Mexico and by importing a part of Mexico’s laborers into this country.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

Barbarous Mexico

-by John Kenneth Turner

C. H. Kerr, 1911

https://books.google.com/books?id=-7VmAAAAMAAJ

-on Cananea Strike

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=-7VmAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA213

IMAGE

Barbarous Mexico, JKT, gold lettering, 1911

https://archive.org/stream/barbarousmexico00turnuoft#page/n0/mode/1up