—————-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday July 2, 1913

“The Paterson Strike Pageant” by Phillips Russell, Part II

From the International Socialist Review of July 1913:

[Part II of II]

The New York Press the next day said:

“The Garden has held many shows and many audiences, from Dowie to Taft to Buffalo Bill, but it is doubtful if there ever was such an assemblage either as an audience or as a show as was gathered under the huge rafters last night. In fact, it was a mixed grouping that at times they converged and actor became auditor and auditor turned suddently into actor. When more than 10,000 sang and shouted within, 5,000 outside clamored for admittance and were willing to pay double the prices to get in.”

The New York Evening World said:

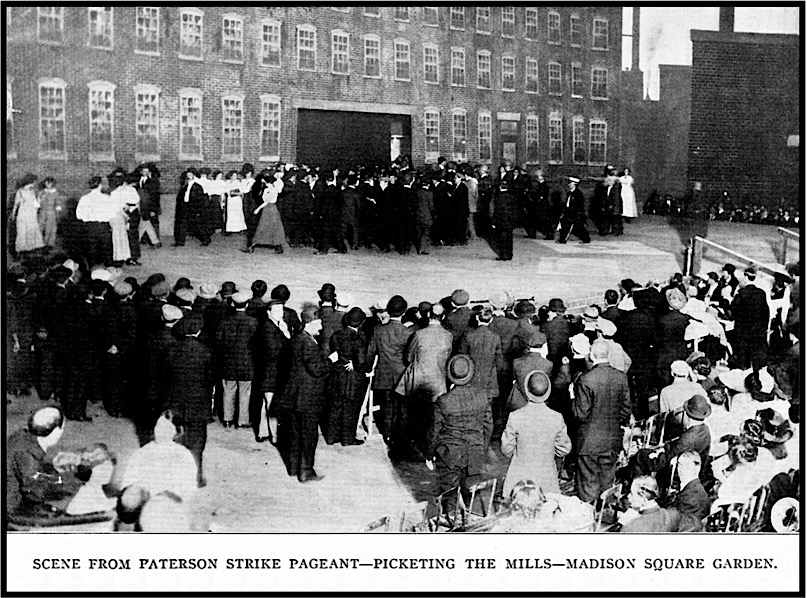

“Fifteen thousand specators applauded with shouts and tears the great Paterson Strike Pageant at Madison Square Garden. The big mill aglow with light in the dark hours of early winter morning, the shrieking whistles, the din of machinery-dying away to give place to the Marseillaise sung by a surging crowd of 1,200 operatives, the fierce battle with the police, the sombre funeral of the victim, the impassioned speech of the agitator, the sending away of the children, the great meeting of desperate hollow-eyed strikers-these scenes unrolled with a poignant realism that no man who saw them will ever forget.”

No spectacle enacted in New York has ever made such an impression. Not the most sanguine member of the committee which made the preparations for the pageant believed that its success would be quite so overwhelming. It is still the talk of New York, most cynical and hardened of cities, and will remain so for many days.

There were times when the committee were assailed with oppressive doubts. When one sat down and thought it over in cold blood, the idea of arranging for and carrying through such a thing in two weeks’ time seemed almost grotesque. Outside of the mechanical difficulties involved, the multitudinous details to be attended to, the advance outlay of money that would be necessary seemed to present an insuperable obstacle. There was the single item of $1,000 to be put down for the rental of one night, the $750 needed for scenery, the huge sum for advertising, all to be provided.

After plunging in with enthusiasm for the first few days, a bad reaction seized the promoters. They called a meeting in which the most gloomy forebodings were indulged in. There were disturbing reports of the small advance sale of tickets and there were serious proposals to give the whole thing up.

It was the workers themselves who stepped into the breach. Delegates from the New York silk strikers, whose cause has almost been lost sight of in the more spectacular struggle of Paterson, arose indignantly.

“What?” they cried. “Give this thing up after our people have set their hearts upon it? Never! Is it money you need? Leave it to us-we’ll raise that! We are poor. We are on strike. But a lot of us still have a few dollars left in the savings bank that we’ve been putting by through many years. We’ll get it out and lump it together. We will go to our business men and say: ‘Here, we’ve been trading with you a long time. We have helped to make your profits. Now you help us or we won’t trade with you any more.’ Never mind. You leave it to us-we will raise the money.”

And they did. Other generous people, more richly upholstered with ready cash, also came forward with contributions and in four days there was ample money with which to cover all deposits.

And it was found that the result was worth all the toil and trouble involved. The lives of most of us are sordid and grey. So tightly are we tied to the petty round of toil to which our galley-masters bind us, that most of us probably are born, live and die without experiencing one deep-springing, surging, devastating emotion. We are either afraid to feel or we have lost the capacity.

The Paterson pageant will be remembered for the sweeping emotions it shot through the atmosphere if for no other reason. Waves of almost painful emotion swept over that great audience as the summer wind converts a placid field of wheat into billowing waves. It was all real, living, and vital to them. There were veterans of many an industrial battle in that audience, though the cheeks of many still held the pink of youth.