—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday March 3, 1914

Herman Suhr and Richard Ford Convicted of Second Degree Murder

From the International Socialist Review of March 1914:

The Wheatland Boys

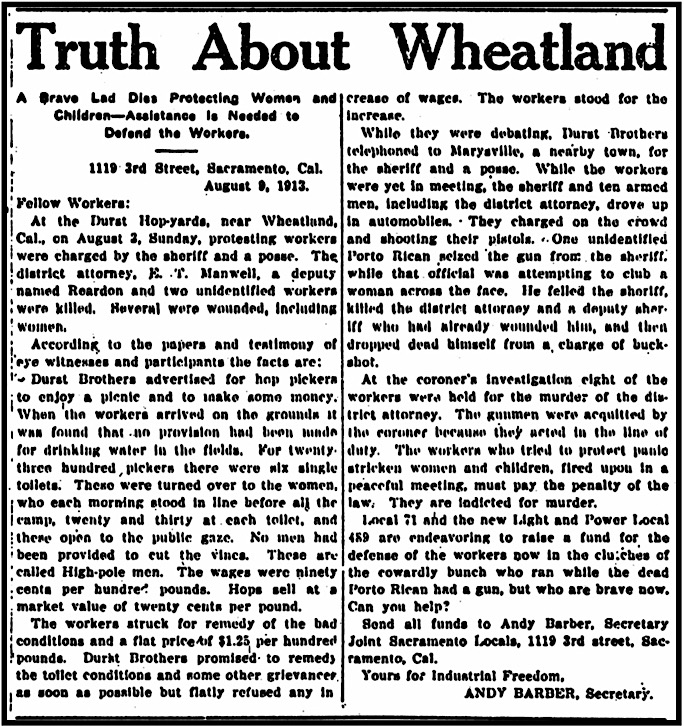

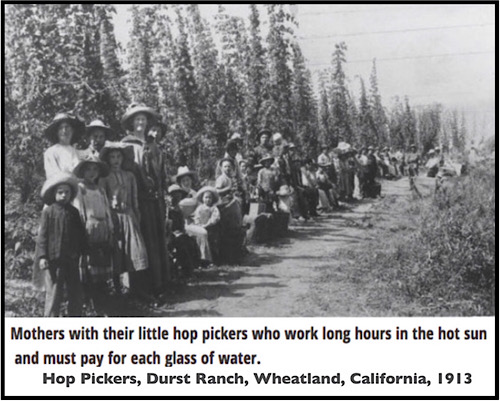

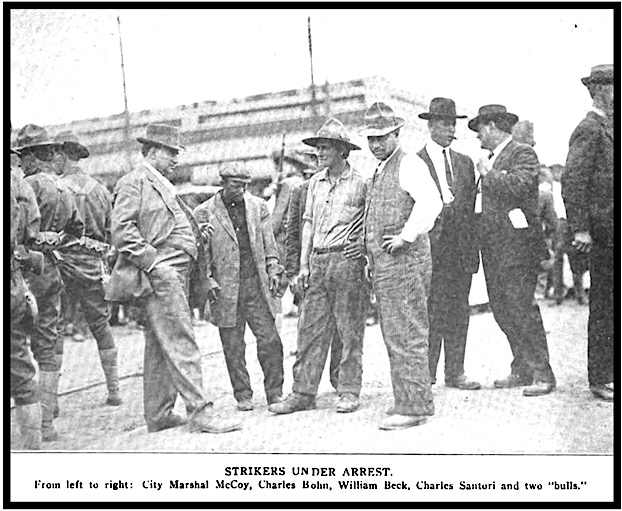

HERMAN Suhr and Richard Ford, leaders of the strike on the Durst Hop Ranch at Wheatland, have been convicted of murder in the second degree, in the trial for the murder of District Attorney Edmund Manwell, killed in the raid of the sheriff’s posse on a peacable meeting of men, women and children strikers. William Back and Harry Bagan, who stood trial with them, have been released “on account of insufficient evidence.”

Ford and Suhr are convicted of murder. But they are not convicted of actually having murdered Mr. Maxwell. They are convicted of conspiring to murder, of being accessory before the fact.

The evidence of several eye witnesses proved that the District Attorney was killed by a Porto Rican, who came to the rescue of his fellow strikers. But the Porto Rican was killed himself; Ford and Suhr were not killed. And, as Prosecuting Attorney Carlin says, “The blood of Ed Manwell cries from the ground for their conviction.” The employing class cry for their conviction, Mr. Carlin might have added with less false sentiment and more truth. For these men, Ford and Suhr, were strike leaders, and their strike promised to be successful, had not the sheriff’s posse acted as strikebreakers for the Hop Barons.

These are the reasons for the conviction of Ford and Suhr. The precedent of a conviction of a labor leader for conspiracy to murder, of being accessory before the fact to any violence fomented by the employers in time of industrial trouble, is choked down the throats of the working class in California. And a staggering blow is given of the organization of the migratory workers, in whose vast army they urge toward organization had just begun to take embryonic shape.

Immediately behind the four prisoners during the trial sat Mrs. Suhr and Mrs. Ford, each with her two children. Suhr is desperately broken by the tortures of the Burns detectives, and even wiry, spirited hopeful Ford shows the long imprisonment and the strain. But the men show their ordeal hardly more than their wives.

As they sat before the twelve men who were to decide their fate, it was difficult to imagine a situation where justice would be more bitterly impossible to secure than in this county of Yuba, from which change of venue had been denied the four prisoners. Not a man in the jury who would not consider (however falsely) that his financial interest would be more secure for the conviction of these men. Not a man there who knew them or had ever looked upon their faces before. Not a man there who did not know at least by reputation, the dead man, his widow and orphans. Not a man who had not read the bitter attacks of the local press, condemning these men to the gallows before they were even brought to trial. Not a man who had ever read a word favorable to them (the reading of the pamphlet [“Plotting to Convict the Wheatland Hop Pickers”] sent into Yuba County by this league having been declared by the judge to disqualify a man from jury service). Not a man in the jury, probably, who did not share the prejudice of the man with a home, against the so-called hobo.

Austin Lewis’ plea for the defense was brilliant, profoundly human and convincing. It took the evidence, as given by both sides and utterly demolished the case of the prosecution with the sword of cold reason, slashed the cowardly Stanwood for his persecutions of helpless prisoners, and then flung itself upward in such an appeal to the blood-kindred of all men in aspirations for betterment and freedom, such as the strike on the Durst Ranch, as must have stirred the blood of every listener. But Lewis was a stranger to the jurymen, and their petty life in an agricultural community rendered it impossible for them to judge in a case involving an industrial question.

Prosecuting Attorney Carlin, who followed, had set his stage well. Opposite the jury sat the widow of the dead man with her six children. Intimately, as a man might talk to them leaning over the front fences, Carlin drove his plea home to the jury, every man of whom knew him, and many of whom, it is stated, were under obligations to him. Analysis of the testimony there was none; argument there was none; reason there was none.

A poor, shabby, cowardly speech, vulgar and dull. But it did not have to be very clever. All was well prepared without a clever plea. The judge read to the jury instructions from the law exactly covering a conviction for conspiracy in these cases, and hastily skipped over the instructions which would have freed the men by showing that Ford and Suhr did not aid and abet the Porto Rican who did the shooting.

The crooked, brutal case was about finished. The prophecy of gentlemen intimately associate with the ever clever Burns detectives to the effect that the verdict would be brought in at 1:30 p. m. on January 31, was correct. Society women and social workers who had come up from San Francisco, representatives of the press, investigators from the new Federal Commission on Industrial Relations, townsmen and townswomen crowded the courtroom. And the impious mock dignity of the law went on its wind-inflated way, to free the two men whom it dare not hold and to pronounce guilty the two whose sole crime was that they rose to lead out of the darkness, a helpless crowd of men, women and children, to convict these men who used what talents were theirs to voice the will and aspirations of these people for clean and decent conditions and a wage sufficient to allow them to hold up their heads as men.

Their cases will be appealed, and the storms of protest and wrath will not be downed until they are free.

[Photograph and Emphasis added.]

—————

————— —–

—–

—————

—————