—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Friday April 18, 1913

Akron, Ohio – The Story of Annie Fejtko, Goodrich Striker

From the International Socialist Review of April 1913:

800 Per Cent and the Akron Strike

By Leslie H. Marcy

[Part III of IV]

The following story printed by the Akron Press, a paper which has tried to give the strikers’ side some showing in this bitter struggle, is the general answer of the women and girls who joined the strike:

Annie Fejtko, eighteen, joined the Akron rubber strikers Friday. She’s all alone in Akron-her own provider, housekeeper, washerwoman-and a mere child.

This is Annie Fejtko’s own summary of what she pays and how she spends it:

Average weekly pay, $4 to $4.50.

Weekly board bill, $3.

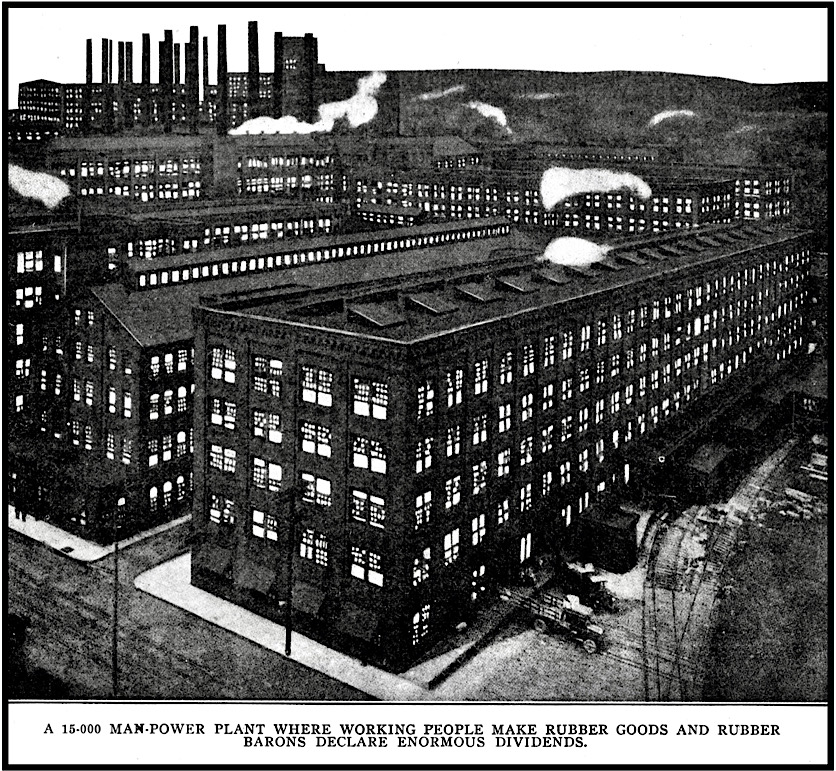

Left for dress, amusements, etc., $1 to $1.50.She came to Akron about a year ago and has been working for the B. F. Goodrich Company ever since. She started to work on 10-hour day work, for $1, a day.

“I only worked that way three weeks,” said Annie. “Then they put me on piece work. My average two weeks’ pay is $8 or $9. I can’t save anything and I haven’t seen papa or mamma or the little brothers and sisters since I came here.

“They only live in Pennsylvania, too, but I can’t save enough to go and see them.”

The last day Annie worked she made 75 cents. Lots of days she said she made less.

“Some days I can make $1.25 and once in a while $1.50, but that’s only when I work on certain kinds of work, and just as fast as I can all day, without resting.”

The highest Annie has ever been paid for a day’s work, was $2. She never made that much again, she says. That day she was cutting paper rings to hold the rubber bulbs in packing. When Annie went home that night her hands were blistered from the scissors.

For some time before the strike Annie had been working in what is known as department 17-B, of the Goodrich. This is the rubber bulb branch. Her work is constantly changed, but for the most of the time she has been inspecting the hard rubber stems for the bulbs, she said. She is paid 9 mills a hundred for this work and makes around $1 when kept doing this all day.

But there’s stamping of time cards to be done, and the work is passed around. “Two mills a hundred is paid for this work,” says Annie, “and if you don’t work all day you couldn’t make over 25 cents.”

“In some of the departments the girls make more,” Annie states. “The buffers (a line of rubber bulb work), make as high as $2 a day when they get to work all the time, but lots of times there isn’t enough to keep them busy. Sometimes they are sent home and other times they stay around all day expecting more to do and only get about 25 cents worth of work.

“But I can’t make that much,” the girl says. “I suppose I’m not fast enough or something. But I work hard, ten hours every day and I have to do my own washing in the evenings, and skimp awful.”

When the strike started Annie didn’t quit. It ran from Tuesday until Friday. She wanted more money for her work, but she didn’t have anything saved and thought she couldn’t afford to lose a day.

“Friday Charlie, one of the pickets talked to me at noon. I decided I couldn’t be much worse off so I laid down my tools and four other girls in that department followed me out,” she explained.

“I haven’t any money and I have to pay board and-” she looked seriously out of the window, “but I suppose they’ll help me.”

“If I don’t get any more, though, when I go back, I don’t see how I can ever catch up out at Santo’s where I board.”

———-

———-

———-

———-

———-

———-