—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday April 29, 1914

Eccles, West Virginia – Mine Explosion Claims Many Lives; All Hope Lost for Missing

From The Wheeling Intelligencer of April 29, 1914:

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday April 29, 1914

Eccles, West Virginia – Mine Explosion Claims Many Lives; All Hope Lost for Missing

From The Wheeling Intelligencer of April 29, 1914:

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Friday January 29, 1904

Pennsylvania and Colorado – Hundreds of Newly Made Widows and Orphans

From The Rocky Mountain News of January 27, 1904:

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday January 27, 1904

Cheswick, Pennsylvania – Sorrow and Dread at Scene of Harwick Mine Disaster

From The Pittsburg Press of January 26, 1904:

—–

—————

—————

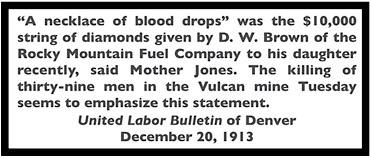

Hellraisers Journal – Friday December 19, 1913

New Castle, Colorado – 37 Coal Miners Dead in Explosion at Vulcan Mine

From Grand Junction (Colorado) Daily Sentinel of December 17, 1913:

…..Among the mine victims of Tuesday are many of the boys who were made fatherless by the previous disaster [Feb. 18, 1896]. Widowed Mothers forced them into the mine again……

“Thank God I am a farmer,” said A. S. Tibbits at 2 o’clock this morning to a Sentinel reporter, after having spent the day in rescue work at the mine.

“I was one of the helpers in the Vulcan disaster eighteen years ago, but this explosion wrecked the mine a dozen times as bad.”…..

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday July 12, 1903

Hanna, Wyoming – Sister of Victim of Mine Fire Not Allowed to Stay at Camp

From The Butte Miner of July 11, 1903:

Mrs. Mary Cooney returned to Butte yesterday from the Hanna coal mine in Wyoming on the Union Pacific, where here brother, John Boney, met his death with 233 other miners through the recent fearful explosion of gas. Besides her grief because of the loss of her brother in so terrible a manner Mrs. Cooney reports having had a very trying experience at Hanna.

It is stated that the managers of the coal property, who virtually own and control the little mining camp, have given strict orders, both at their store and to the residents that no eatables or other supplies or entertainment should be given or sold to any strangers or visitors to the camp. It was given out that the reason for this order was that the families of the miners who were killed were all destitute and could not give up anything to new-comers.

It was not explained, however, why the company store would not provide strangers and visitors with eatables, as the railroad company that owned the mine and the camp could easily ship in any day whatever was needed.

Under these conditions Mrs. Cooney was compelled to go back and forth to Medicine Bow, a station on the railroad twenty miles distant. Mrs. Cooney was accompanied on her sad mission by her daughter, Mrs. Felix Ogier, also of Butte, and during the time taken up with the arrangements and the funeral they had to make the trip back and forth to Medicine Bow station every day.

Another act of the mine company that is complained of is the order that was given in regard to the papers and other valuables that were found in the cabins and trunks of the 234 miners who met their death. The papers and other belongings of the men were all taken to the company store, and inquiring friends and relatives, it is stated, were not allowed to have access to the property or even inspect it.

Mrs. Cooney signed papers petitioning the appointment of a resident of Hanna as administrator of her brother’s estate, and it is expected that soon, through the courts, the administrator will secure possession of the estate. Mrs. Cooney is the mother of Deputy County Clerk John Doran, of Butte.

John Boney was buried at Carbon, a station twelve miles from the scene of the awful disaster. He was laid beside his father, who died and was buried at Carbon a number of years ago.

The bodies of only two other miners besides John Boney were recovered from the blazing mine interior. The mine is on fire in every portion, and it is impossible to reach the workings where the men met their deaths, it being a great distance from the surface. The tunnel from the main entrance slopes gradually for a mile and a half, and from that point there are seventeen miles of workings on sixty-nine levels.

As all hope of rescuing the 31 bodies has been given up the work of sealing up all openings to the mine has been commenced. This step is taken with view to smothering out the flames that are raging fiercely in all parts of the mine.

It is currently believed at Hanna that the precautions being taken by the company to discourage visitors from coming to the camp and from remaining there after they do come is with the object of diminishing as much as possible the amount of evidence that will be available against the company in case of damage suits. There is considerable talk of blame being attached to the management for the disaster, and it is not desired that there should be any inspection of the conditions at the mine or interviews with the residents.

[Emphasis added.]

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday December 31, 1922

Pennsylvania Law for Protection of Anthracite Miners Set Aside by Supreme Court

From the Duluth Labor World of December 30, 1922:

COURT DECLARES LABOR ACT VOID

———-

Pennsylvania Mine Cave-In Law

Held to Be Confiscatory

———-

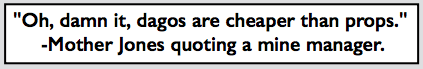

The United States Supreme court has set aside the Pennsylvania law which prohibited the mining of anthracite coal in a manner that would endanger the lives or injure the property of persons-occupying houses situated on the surface soil. Justice Brandeis dissented.

The court held that the law deprived coal owners of valuable property rights without compensation. Under the decision, coal owners can mine coal without any regard for cave-ins that endanger lives and property, unless the coal that is necessary for props is paid for.

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Brandeis said:

If by mining anthracite coal the owner would necessarily unloose poisonous gases, I suppose no one would doubt the power of the state to prevent the mining without buying his coal field. And why may not the state, likewise, without paying compensation, prohibit one from digging so deep or excavating so near the surface as to expose the community to like dangers? In the latter case, as in the former, carrying on the business would be a public nuisance.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Saturday November 25, 1922

Dolomite, Alabama – Death Toll from Mine Explosion Reaches 84

From the Birmingham Age-Herald of November 24, 1922:

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Friday November 24, 1922

Dolomite, Alabama – Mine Blast Claims Lives of at Least 70 Coal Miners

From the Birmingham Age-Herald of November 23, 1922:

—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Friday November 10, 1922

Spangler, Pennsylvania – Explosion at Reilly No. 1 Mine Claims Many Lives

From the New York Evening World of November 6, 1922:

-(Note: final death toll expected to be 79.)

From the Washington Evening Star of November 9, 1922:

[Emergency Crew at Work]

[Survivors at Spangler Miners’ Hospital]

—————

—————

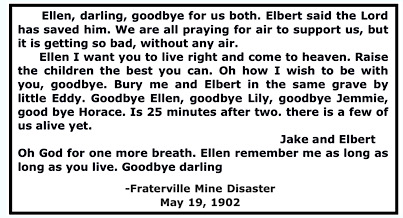

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday May 22, 1902

Coal Creek, Tennessee – At Least One Hundred Men and Boys Lost in Mine Explosion

From the Akron Daily Democrat of May 19, 1902: