The bosses ride fine horses

While we walk in the mud,

Their banner is the dollar sign,

Ours is striped with blood.

-Aunt Molly Jackson

Hellraisers Journal, Tuesday October 31, 1916

Immigrant or American-Born, Neither Matters When Workers Strike

Today’s Hellraisers presents two stories of striking workers driven from their homes by company gunthugs. The strikers in Utica, New York, are mostly Polish immigrants. In Hardin County, Illinois, there are very few immigrants, most of the strikers are second or third generation Americans. But we find from these two stories that neither the striker of foreign birth nor the native-born striker can expect any mercy from the gunthugs hired by the companies and deputized by the county sheriff.

From the Duluth Labor World of October 28, 1916:

2,700 POLISH TEXTILE STRIKERS DRIVEN

FROM HOMES IN NEW YORK

—–BRUTAL GUARDS ASSAULT WOMEN

TEXTILE WORKERS

—–

By DANTE BARTON.

Member Industrial Relations Committee.

NEW YORK, Oct. 26.-Right in the heart of central New York, prosperous and boasting of its wealth, there is now an example of cruelty, incompetence and lawlessness against striking workers which rivals the things done in Colorado by the Rockefeller interests, or on the Mesaba range or in Pittsburgh, by the Steel trust.

Just outside of Utica, in the little town of New York Mills, 2,700 Polish men and women, industrious and peaceful, are being thrown out of company houses, terrorized and assaulted by armed thugs and guards, their children sickened and in many instances killed by the diseases of exposure; themselves and their families subjected to starvation and sickness.

These things are being perpetrated against them by their employer, the New York Mills corporation, of which A. D. Juilliard, New York city, is the responsible president, because they have struck for a 10 per cent increase of wages that are too low, by any standard, for decent living.

These statements are made after personal investigation by the writer.

These striking weavers and spinners have been forced to live in company houses, many of them in bad repair, most of them overcrowded, and many of them infected by indescribably filthy privies, set within a few feet of the kitchen and living room doors.

In one such company house a very poor widow lived with five small children, ranging in age from two to five years. This woman was a worker in the mills. Her wages before the strike had been seven dollars a week, from which the company deducted one dollar a week for house rental.

Every three months $1.40 was charged her for water. Not as far as 10 feet from the door of the room in which the widow’s babies slept was a privy, a broken door, foul and horrible.

Companies Violate Laws.

One of these same law-violating privies was maintained by the companies in the backyard of the miserable cottage that is now being used as a hospital for the very sick children of the workers. The warning sign, “Infantile Paralysis,” is posted on the front door.

In the adjoining house children lived, and were playing in the yards of the “hospital” and the house with no fence between.

A short time ago A. D. Juilliard, president of the company that thus exposes the lives of little children, gave a hospital boat to the city of New York for the use of little children.

—–

[Photograph added.]

From Life and Labor of October 1916:

The Strike at Rosiclare

Report of the Committee of Investigation

Appointed by the National Women’s

Trade Union League of America

Illinois seems about to have its own Ludlow. There has been no shooting of women and children yet; no fires have been started in tent colonies, but those things will come if the present reign of lawlessness at Rosiclare continues.

Rosiclare is a little village of about a thousand inhabitants in Hardin county. It is not on a railroad; there is not a railroad in the county. The nearest station is Golconda, about twenty miles away.

There are no industries in the county, except the spar mines at Rosiclare. Here about 450 men were employed until the strike was called on the 2nd of June. The county had not a labor organization within its borders until these miners formed their union last spring.

Hardin county has practically no immigrants. The people there and their fathers and grandfathers were born in this country, most of them in southern Illinois and in Kentucky.

It is a community of churches. There are four church organizations in Rosiclare. A large proportion of the miners are church members and active workers in the church. One of the leaders of the strikers, a hoisting engineer, has the walls of his work room covered with pictures given out by the Sunday school.

It is anti-saloon territory, and the law is enforced. Until the mine owners put their gun men on the street, very little liquor was brought into the town. The gun men, of course, need it to nerve them to their work.

One of the striking miners is president of the village, and three of them are members of the board of trustees. All three are active anti-saloon men and have been vigorous in the prosecution of boot-leggers.

The miners organized because conditions compelled them to. Wages were low and working conditions bad. The companies state that the men make five and six dollars a day. At the McLean mines (the conditions at the other mine, the Fairview, are the same) out of 250 men only three or four earn five dollars a day, and their working conditions are such that they cannot remain at the work longer than ten years. Few of the men can stand it longer than five years. Five men (engineers and steel sharpeners) get three dollars a day. Perhaps ten or fifteen get two dollars and a half. The remainder get a dollar and a half, a dollar seventy-five and two dollars a day, the large majority receiving less than two dollars.

The hours are long. Many of the men work twelve hours a day, none less than ten. And they work seven days a week, habitually some of them, and all of them are frequently called out on Sunday. For a man to refuse to work on Sunday means instant dismissal. One of the miners is an ordained preacher, serving a little church out in the country. He asked to be excused from Sunday work, so that he might carry on services there, but this was denied him. He was told that his place was in the mine when there was work to do.

Another time the wife of one of the miners had joined the church and was to be baptized at the morning service. The men were ordered to work that Sunday. He stated his case to the superintendent and requested that he be allowed to attend the church service. He was ordered to go to work, and dared not refuse for fear of losing his job. Another man who had lost his son was directed to return to work immediately after the funeral services. He did not go back to the mine until the next morning, and then he was discharged.

The air in the mines is foul, and most of the underground men have to work in water. The statutes passed for the health and safety of miners apply for the most part only to coal mines. And few have been the mining companies that ever did anything to protect the lives and health of the men except as they were compelled to do so by law.

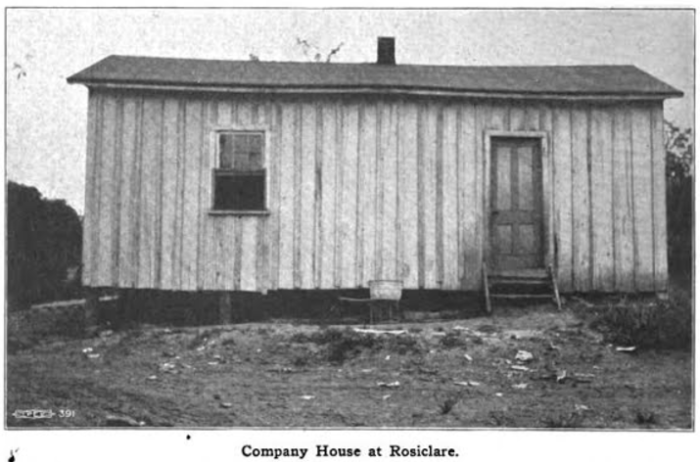

The miners live mostly in company houses. Few of them can afford to live anywhere else. These houses are mere shacks. The families have no carpets on the floor or pictures on the walls. The clothes of the children are merely rags. “Company row” presents a picture of utter desolation.

These were the conditions that caused the organization of the union. No “labor agitator” from the outside organized these men. They did the work themselves. About two years ago some of them came to realize that if they were ever to get living wages or decent working conditions they must organize. They talked it over among themselves. Others joined them. The work proceeded slowly, because the men had to be cautious about whom they would take in.

Early in May of this year a company spy learned what was going on and reported to his superiors. Sixty—eight men were known to have joined the union, and they were immediately discharged. But the work of organizing went on. A committee of the men went to see the company’s representatives. They asked for a twenty—five per cent increase in wages, an eight-hour day and the right to present grievances through a committee. They were told that the company would not deal with them or with the union, and that any man who did not like conditions there could quit.

A strike was called, and the men walked out. When the sixty-eight men were discharged, the company put on armed guards, whom the sheriff made deputies. Immediately upon the calling of the strike a reign of terror was inaugurated. Fifty to seventy-five men armed with rifles and revolvers have been parading the streets of Rosiclare. They are not kept at the mines to guard property, but march through the streets of the village to terrorize the miners. They have driven peaceable citizens from their homes and out of the village. Most of the miners and their families have been compelled to leave their homes and the village and remove to Elizabethtown, five miles away, where the union has succeeded in providing shelter for them.

These gun men are of the usual type. Many are not residents of the state, but were brought in by the company from Kentucky. One had been convicted and fined for knocking his sister down; another is known as a habitual wife beater, and one has been out of the penitentiary less than a year, where he served a sentence for shooting a boy in the back.

These men are now in possession of the town. They say the town is under martial law, and arrogate to themselves all authority. They refuse to permit the village trustees to meet, or the village officers to exercise any of the powers given them by law. They have driven the president out of town. The village clerk, a member of the union, had saved up enough money to start a little grocery store. They compelled him to turn his stock back to the wholesalers and leave the village. Trustees who were union men or sympathized with the union were driven out, and one who did not go was ordered to resign as trustee.

About 500 people, altogether, have been either driven out, or so terrorized that they dared remain no longer. Among them were many pregnant women. One-of these could find no other shelter and was compelled to sleep in a cave one night. The fright and the hardship have caused miscarriages and premature births.

One old lady was just sitting down to her supper when ordered to leave by a gun man. She asked permission to eat her supper. The reply was, “Never mind the eating, get out!” She, too, slept in a cave. One gun man went to his own sister and ordered her and her husband to leave town, and a minister who in his sermon spoke of his sympathy for the men in their effort to better their condition was met after the service by a gun man and told to leave immediately.

One curious feature of the situation is the frank acknowledgment of the deputy sheriff in charge of the gun men that he cannot control them. Sneed, of the United Mineworkers, went to Rosiclare to investigate conditions. He was ordered by the deputy not to stay in town over night. Mr. Sneed is a Mason, an Odd Fellow, and a deacon in the Baptist church—not at all a dangerous man to have around. He refused to go, stating that he had not disturbed the peace and was guilty of no crime; that he had a right as a citizen of Illinois to stay in Rosiclare and there he proposed to remain. The deputy sheriff admitted this, but begged him for his own safety and the safety of the family with whom he was staying to leave town, for he, the sheriff, could not control these gun men.

Miss Mary Anderson and Miss Agnes Burns, for the Women’s National Trade Union League, went to the town on the 8th day of September to hold a meeting for the wives of the strikers in the yard of L. T. James. They were met by the deputy, who told them they could not speak, for if they did there would be a riot. Miss Anderson asked who would riot, saying that neither they nor the people to whom they proposed to speak would do any rioting. “Why,” replied the deputy, “the men from the mines will come up, and I cannot control them.” He further declared that the town was under martial law, the sheriff having usurped the authority of the governor.

Miss Anderson and Miss Burns spoke. While they were speaking men did come from the mines. Wives of the scabs also came, and disorderly women of the town. They shouted insulting remarks at the speakers and the miners’ wives, endeavoring to incite them to acts of violence. That failing, one of the gun men struck the president of the village, who was present, in the face with his fist. Had the president lost control of himself and retaliated, the papers next morning would have carried the story of a riot precipitated by the strikers and their sympathizers and how the deputies had been compelled to shoot to save the lives of the wives of the non—union miners and restore order.

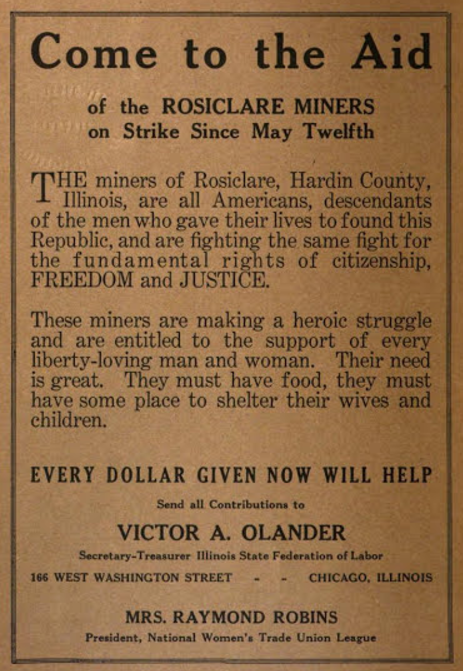

These are a few of the things that are happening in the ordinarily peaceful and placid village of Rosiclare. The miners have courage and will win this fight. But they need your help and need it now.

They will win the fight because the spar they mine is needed in industry and can be obtained nowhere else. Ninety per cent of the spar produced in the United States comes from the two mines at Rosiclare. It is used for many purposes. Among others, an acid derived from it is used in the making of munitions. And that must be had now by those who are fattening on war contracts. They cannot afford to have the strike go on. Up to this time a stored supply has been shipped out, but that is nearly exhausted. The companies will be forced to settle with the miners if the strike is continued a little longer.

The men have the will to fight. But their families must be fed. You must help feed them. The winning of this fight means much to organized labor. This is the first union organization to be formed in Hardin county. Many factories are now going in. This will soon be an industrial center. With this strike won, every factory will be organized as soon as opened. With this fight lost, every shop will be a scab shop for years to come.

This is the time to give. Give as much as you can and give quickly. Send all contributions to Victor A. Olander, secretary-treasurer Illinois State Federation of Labor, 166 W. Washington street, Chicago, Ill.

WM. H. HOLLY,

Attorney for National Women’s Trade

Union League of America.MARY ANDERSON,

Organizer N. W. T. U. L. of A.AGNES BURNS,

Member Illinois State Committee

N. W. T. U. L. of A.[Paragraph breaks and emphasis added.]

Appeal for aid for Rosiclare Strikers:

SOURCES

The Labor World

(Duluth, Minnesota)

-Oct 28, 1916

https://www.newspapers.com/image/49876686/

Life and Labor, Volume 6

National Women’s Trade Union League, 1916

https://books.google.com/books?id=ls49AQAAMAAJ

L&L Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=ls49AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA145

The Strike at Rosiclare by WTUL

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=ls49AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA157

IMAGES

A. D. Juilliard (1836-1919), wiki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_D._Juilliard

Rosiclare Miners Company House, Life and Labor, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=ls49AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA158

Rosiclare Miners Strike, Life and Labor, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=ls49AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA146

I Am A Union Woman – Deborah Holland

Lyrics by Aunt Molly Jackson

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/unionwomanmollyjackson.html