~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Saturday April 6, 1918

Victory! for Packinghouse Workers by William Z. Foster, Part II

From Life and Labor of April 1918:

HOW LIFE HAS BEEN BROUGHT

INTO THE STOCKYARDS

A Story of the Reorganization of the Packing IndustryWilliam Z. Foster

Secretary Chicago Stockyards Labor CouncilThe main questions, touching wages, hours and conditions of labor, involved in the Stockyards arbitration hearing before Judge Alschuler, and his decision concerning them, are of overwhelming importance, both in principle and in consequence. Just how far-reaching will be the results of the decision one cannot now forecast. But lips stiffened by poverty will perhaps now learn to smile, and thousands of families will for the first time taste of life.

[Part II]

DRASTIC ACTION TAKEN

The cup was full. It was evident that the packers had no intention of living up to their agreement, but were seeking openly to destroy the unions, let the consequences be what they might. The unions accepted the issue. They at once broke off negotiations with the packers and sent the committee away to Washington again to demand that the President take over the packing houses, as the only way to guarantee their operation during the period of the war.

On January 18th the committee met with President Wilson, explained to him the imminent danger of a great strike in the packing houses and asked that he take steps to seize the industry. The President replied that the proposed remedy involved a big issue, that he would take it under advisement, and that in the meantime another, effort would be made to get a settlement through arbitration.

Accordingly the packers were called to Washington, and later, under the chairmanship of the Secretary of Labor, brought into a joint meeting with the representatives of the unions. But the ice was not yet broken. The packers still held aloof, ignoring the union men and addressing themselves solely to the chair. Soon tiring of this nonsense, John Fitzpatrick, true to his reputation, stepped across the room, grabbed J. Ogden Armour by the hand and introduced himself. Then a little humanity crept into the meeting, and soon the various representatives of Capital and Labor in the packing industry, after their long period of open war, were making a shape at patching up their differences.

The upshot of the meeting was that Frank P. Walsh and John Fitzpatrick, representing the unions, and Carl Meyer and J. G. Condon, representing the packers, were instructed to get together and agree on as many as possible of the eighteen demands of the workers. The result was that twelve of the demands, relating to the handling of grievances and other shop regulations, were, with minor changes, agreed upon. The other six, relating to wages and hours, were to go to arbitration at once. Whatever increases in wages were allowed by the arbitrator were to be effective as of January 14th. Later on the independent packers also accepted this agreement. The articles agreed to were framed and posted in all the packing houses of the country.

THE ARBITRATION OPENS

The selection of the new administrator was fraught with difficulty. The names submitted by the men were rejected in toto by the packers, and vice versa. Agreement was out of the question on this point. Finally the Secretary of Labor, adhering to the terms of the original agreement of the President’s Mediation Commission, and after securing the approval of the National Council of Defense, appointed Federal Judge Samuel Alschuler to take the place of Mr. Williams, resigned. Upon this man came to rest the full responsibility of establishing the standard of living of the 500,000 people dependent upon the packing industry. Truly a heavy responsibility.

Promptly on time, according to the agreement, Judge Alschuler opened his court of arbitration on February 11th, in the Federal Building, Chicago. Throughout the proceedings, which were public, throngs crowded the court room.

The outstanding feature of the hearing was the exposure of the workers’ overwhelming, crushing poverty. It was as if the characters in “The Jungle,” quickened into life, had come to tell their story from the witness chair. So harrowing and shameful were the tales of misery and despair brought forth that even the tory Chicago Tribune strongly condemned the packers for “social incompetency” and declared that any industry which does not give its workers a living wage should cease to exist.

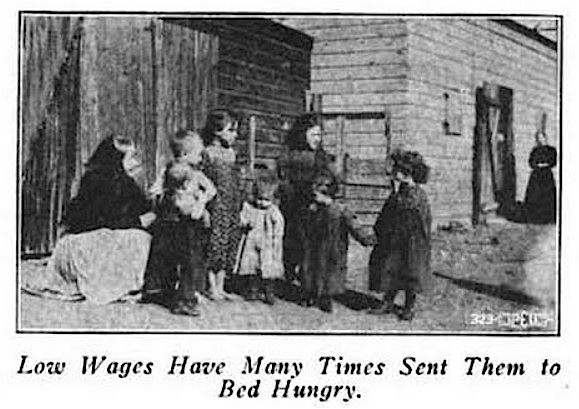

In broken English, or through interpreters, the worker witnesses told the “short and simple annals” of their bleak and barren lives. Educational institutions, public parks, theatres, were nothing to them. Many confessed that they had never even visited a moving picture show. They counted themselves fortunate if, at the cost of hard work and bitter struggle, they could secure enough of the barest necessities to keep body and soul together. One woman, a widow, told a typical story of how her husband, a rugged Pole, came to this country a few years ago, went into the packing houses, fell sick with tuberculosis, continued to work ten to fourteen hours daily to support his family, till finally, “when he had no more blood left” the packers sent him home to die, leaving her and her brood of children poverty-stricken.

Another woman, telling a similar of exploitation and suffering, was, like many others, hatless. Asked why, she replied that several years before, when she came over from Poland, she had had a hat, but it had worn out and she had never been able to buy another, contenting herself with a miserable head-shawl. Asked if she would like to have a hat, she said that what she wanted was food for herself and her children. But supposing she had plenty of food, then would she want a hat? The idea was incomprehensible to her; she wanted food. She couldn’t conceive of a condition in which she and her little ones would have enough to eat. She couldn’t get past the food question. That was the be-all of life to her. A hat—that was beyond her dreams of extravagance. To such depths have the packers, in their unbridled greed, reduced their workers.

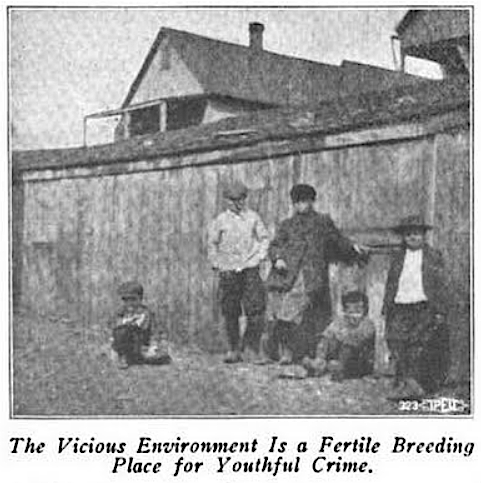

Thus it went for days, witness after witness telling the most shocking stories of overwork, underpay, disease, poverty and suffering. The whole city was startled and shamed at the recital. And finally, to impress still more strongly upon the administrator the deplorable working and living conditions of the packing house workers, the unionists proposed that he make a trip through the great plants and the slums “back of the Yards” in order to see things for himself. The trip was made and consumed two days. More than once the administrator was horrified and sickened by the conditions disclosed.

LABOR NOT A COMMODITY

Confronted with damning evidence that the workers were literally starving while the companies were rolling in wealth, the packers, through their attorneys, boldly attempted to escape the responsibility. Why make a horrible example of the packing industry, asked they? It is little, if any, worse than many others. Granted that “back of the Yards” there are fifteen charitable institutions running full blast, and that the district is rampant with every disease and weakness of slum life. What of that? Things are no better in the Ghetto and the steel districts. If the employers of the dwellers in these sections can get away with it, why pick on us?

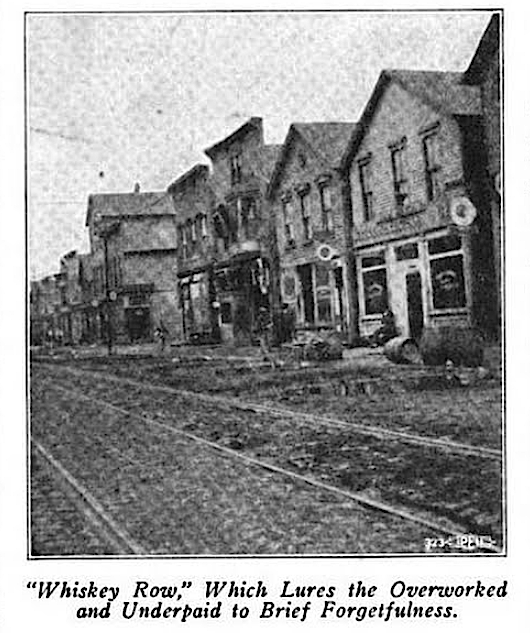

To bolster up their contention that the Stock yards workers’ poverty results from excessive drinking the packers submitted a map showing over 300 saloons in the comparatively small district, “back of the Yards.” But it proved a boomerang; the workers turned it against them. They demonstrated the close connection between hard, ill-paid work and heavy drinking. Samuel Gompers stated that there are two great classes of intemperates, those who work too much and those who work too little. The heaviest drinkers are those who work the hardest for the least money, and those wealthy idlers who do no work at all. The intemperance of Stockyards workers is not the cause of their poverty, but the result of it.

And then, why ascribe poverty to low wages? Authorities are by no means agreed upon that. The prohibitionists say that it is due to drink. The preachers claim it is the result of sin. The Republicans point out the low tariff as the cause. Others blame it upon thriftlessness, sun spots, and what not. But, said the packers, even if poverty should come from low wages, which of course it does not, we would not be at fault. We are business men and we act according to business principles. We buy labor in the open market. And we pay for it almost as much as the Steel Trust, the International Harvester Company and other enlightened and liberal corporations. We use no compulsion. It is none of our business how our workers live. If they accept our wage it shows they must be satisfied. We don’t pry into their lives. We buy labor just as we do any other commodity necessary to our business. And there our responsibility ends.

Against the cold-blooded sophistry that labor is entitled only to what it can get through cutthroat competition, the workers, under the able leadership of Mr. Walsh, turned their heaviest guns. In the language of the Clayton Act, they declared that “Labor is not a commodity or article of commerce,” it is living, breathing humanity, and must be treated as such. They riddled the argument of a fair bargain between great corporations and individual workers, citing as proof the letters being brought to light from day to day before the Federal Trade Commission by Francis J. Heney, wherein, over their signatures, the packers admit buying up a chief of police, misusing government officials, curtailing production, discharging and locking out union men, etc., in order to overawe their workers and to prevent the consummation of that fair bargaining they now prate about so loudly. The unionists flatly demanded a living wage for packing house workers, regardless of the so-called laws of competition and the rates paid generally in other enslaved industries.

DAMAGING ADMISSIONS BY PACKERS

Following this line of attack they called the great potentate of the packing business, J. Ogden Armour, to the stand and brought him to admit that his employes were entitled to and should get a living wage, one sufficient to guarantee them wholesome food, sanitary homes, comfortable clothing, an opportunity for education, and the simpler recreations. Nelson Morris, another magnate packer, was also brought to the stand and induced to agree to the same. It is difficult to see how these big capitalists could do anything else, when brought into the bright glare of publicity, than grant the creators of their immense wealth at least enough to live upon and to reproduce their kind.

The workers submitted four yearly cost-of-living budgets. They represent different standards of living for toilers, graduating from the starvation line to comparative comfort. All were based on elaborate and exact studies. They follow: Bare Existence, $1177.95; Minimum Standard, $1288.84; Minimum Health, $1434.64; Minimum Health and Comfort, $1551.30. The first, third and fourth were submitted by the Bureau of Applied Economics, presided over by the noted statistician and economist, W. Jett Lauck, who, together with two associates, testified in the arbitration. The second budget was revised from one used in the Chicago street car men’s controversy three years ago.

The admissions of Messrs. Armour and Morris involved their lawyers in difficulties. They had to accept the issue of a living wage whether they would or not. They were compelled to present some sort of an estimate of what a worker can barely scrape along on. Then occurred a remarkable thing. The United Charities of Chicago, after mysterious conferences with a representative of the Armour welfare department, had an inspiration that they, too, should send a budget to the arbitration. Did the packers’ lawyers go to the organized charities for the deliberate purpose of establishing a pauper standard of living in the packing industry? For their sakes we hope not. However, if they did they got badly burned. They found that the standard of living of Chicago paupers was far above that of packing house workers.

The United Charities budget, based on the amounts they actually allow destitute families in the Stockyards district, together with an item of $108, added by them for things indispensable where the head of the family works, totaled $1106.82 per year. On the other hand the actual wage earned by packing house laborers, and they constitute 70 per cent of the total working force, averages about $800 yearly. In other words organized charity, “cramped and iced,” pays to paupers $300 per year more than the packers pay their laborers for working ten hours a day, 300 days a year in the rich and productive packing industry! [Emphasis in original.]

Has American industry ever shown a greater shame? Workers paid less than paupers. The packers’ lawyers shied violently from the United Charities budget. To raise their workers up to the standard set by it would require that their whole wage demand of $1 a day increase be granted. The unionists, on the contrary, made good use of the budget. They held that it constituted the best possible proof of the entire justification of all their wage demands. For who would dare to say workers should not have at least as much as paupers?

SOURCE & IMAGES

Life and Labor, Volume 8

-Jan to Dec 1918

National Women’s Trade Union League, 1918

https://books.google.com/books?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ

L&L April 1918

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA62-IA1

Life Into Stockyards by WZF

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA63

See also:

Hellraisers Journal, Friday April 5, 1918

Victory! for Packinghouse Workers by William Z. Foster, Part I

On the Alschuler Award: “How Life Has Been Brought into the Stockyards”

Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clayton_Antitrust_Act_of_1914

See Samuel Gompers on the Clayton Act

From Oct 1914 edition of American Federationist:

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=nqRHAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA860

We Have Fed You All For A Thousand Years – Bruce Brackney