Hellraisers Journal, Friday April 5, 1918

Victory! for Packinghouse Workers by William Z. Foster, Part I

From Life and Labor of April 1918:

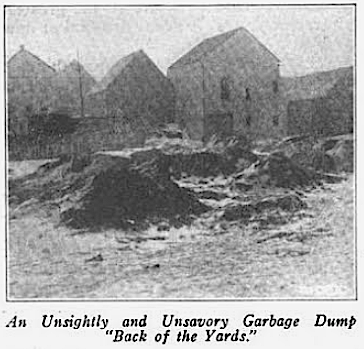

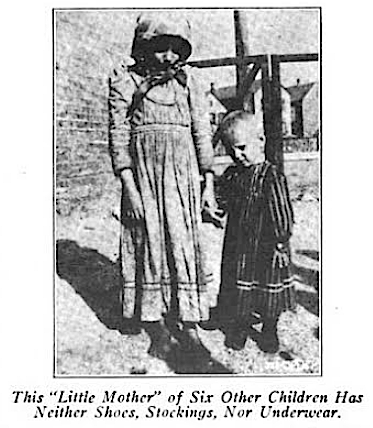

The main questions, touching wages, hours and conditions of labor, involved in the Stockyards arbitration hearing before Judge Alschuler, and his decision concerning them, are of overwhelming importance, both in principle and in consequence. Just how far-reaching will be the results of the decision one cannot now forecast. But lips stiffened by poverty will perhaps now learn to smile, and thousands of families will for the first time taste of life.

[Part I of III.]

EIGHT MONTHS ago the vast army of packing house workers throughout the country were among America’s most helpless and hopeless toilers. Practically destitute of organization, they worked excessively long hours under abominable conditions for miserably low wages. Hope for them indeed seemed dead. But today all this is changed. Like magic splendid organizations have sprung up in all the packing centers. The eight hour day has been established, working conditions have been improved and wages greatly increased. From being one of the worst industries in the country for the workers the packing industry has suddenly become one of the best.

The bringing about of these revolutionary changes constitutes one of the greatest achievements of the Trade Union movement in recent years. A detailed recital of how it occurred is well worth while.

Since the great, ill-fated strike of 1904 the packing trades unions had put forth much effort to re-establish themselves. But, working upon the plan of each union fighting its own battle and paying little or no heed to the struggles of the rest, they achieved no better success than have other unions applying this old-fashioned and unscientific method in the big industries. Complete failure attended their efforts. No sooner would one of them gain a foothold than the mighty packers, almost without trying, would destroy it.

The logic of the situation was plain. Individual action had failed. Possibility of success lay only in the direction of united action. Common sense dictated that all the unions should pool their strength and make a concerted drive for organization. Therefore, when on Friday, July 13, 1917, exactly thirteen years after the calling of the big strike, Local No. 453 of the Railway Carmen proposed to Local No. 87 of the Butcher Workmen that a joint campaign of organization be started in the Chicago packing houses, the latter agreed at once. The two unions drafted a resolution asking the Chicago Federation of Labor to call together the interested trades and to take charge of the proposed campaign.

Thirteen years of unbroken defeat had convinced almost everyone that it was utterly impossible to organize the 60,000 Chicago packing house workers. But upon the proposal of the new plan of joint action the Federation, with an unconquerable faith in the power of unionism, threw itself wholeheartedly into this latest effort. The resolution passed unanimously. Then President John Fitzpatrick took hold in dead earnest. Throughout the entire movement his able assistance was invaluable. He first assembled representatives of all local organizations having jurisdiction over packing house workers, including the butchers, blacksmiths, coopers, colored laborers, egg inspectors, electrical workers, horseshoers, journeymen barbers, leather workers, machinists, office employes, painters, railway carmen, sheet metal workers, stationary firemen, steam engineers, steam fitters, structural iron workers, switchmen, teamsters and women workers. Many of these unions hadn’t even one member in the Stockyards, but on July 25th they were drawn up together into a permanent body, the Stockyards Labor Council, and given the big task of organizing the multitude of oppressed and defeated packing house workers.

SOME INTERNAL PROBLEMS

From its inception the Stockyards Labor Council proceeded on the theory that success in organization work depends almost wholly upon the strength and intelligence of the organizing force. It scorned the idea that any workers are “unorganizable,” considering such a conception to be merely an excuse for Trade Union incompetence to hide behind. It knew that if it could make a sufficiently powerful appeal to the workers the latter were bound to respond, be they never so defeated and discouraged. Therefore, the Council felt that its really big task was to organize itself rather than the packing house workers. Its problem was chiefly internal, not external. If it could succeed in creating an effective organizing force the actual bringing of the immense army of workers into the unions was bound to ensue.

With this right-side-up conception of its problem before its eyes the Council turned in upon itself and began to organize. Its first job was to bring about the indispensable community of action between the score of affiliated unions. But how was it to be done? Some advocated a continuance of the old tactics of individual action, counting for success upon the added volume of effort. Others flew to the opposite extreme and demanded straightout industrial unionism. Finally, after much travail, the solution was found in the federation plan, which has proved so successful on the railroads. But before it could be established and the organizations welded together into one body the permission of a dozen internationals had to be secured.

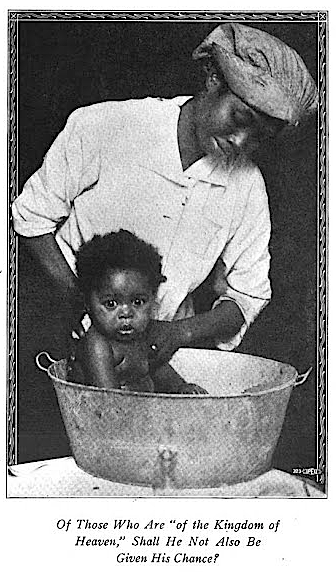

The next problem was the negro question. This was serious. About 12,000 colored workers are employed in the Chicago packing houses. They work in all the trades. To organize them was imperative. They were very suspicious and distrustful of the unions, due largely to the propaganda of the packers. The fact that many of the organizations drew the color line was enough to ruin the whole proposition. The difficulty had to be gotten around or inevitable failure would result. A place had to be made in the movement for every negro in the packing houses. The situation was laid before President Gompers. He grasped it at once and agreed that, provided no serious objections were raised by the internationals involved, special charters should be granted to colored workers engaged in trades where they were barred by the regular unions. This liberal measure removed a great obstacle to the organization of the packing house workers.

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS

Finally, after eight weeks intensive organization of itself, the Council felt ready to enter upon the second stage of its big undertaking, to actually bring the workers within the folds of the unions. All the affiliated organizations had been combined into a harmonious whole and infused with a do-or-die spirit. A place had been found in the ranks for every man, woman and child working in the packing houses. A competent corps of organizers had been assembled, two of whom, colored men, were coal miners, whose services were donated by the Illinois miners. Then, on September 9th, the organization campaign began with a roar. Rarely had it been equaled in this country. For weeks huge hall and street meetings, parades, automobile demonstrations and smokers followed one another in rapid succession. Over 500,000 pieces of literature, in various languages, were distributed.

Then the inevitable happened. Gradually the workers aroused from their lethargy. In organization they began to see relief from their poverty and oppression. Due largely to the splendid work of John Kikulski, A. F. of L. Polish organizer, the great army of laborers first began to move. Then came the skilled trades. To begin with the workers came slowly. Then, as their confidence rose, they came in a mighty flood. As many as 1,400 joined at one monster meeting. The organizers were swamped. The opposition of the companies was fruitless. Increasing wages and working hardships upon the unionists alike proved powerless to stem the swelling tide of organization. A living torrent poured into the unions. This continued for weeks until, finally, after thirteen long years of bitter struggle, Organized Labor found itself again firmly intrenched in the packing industry. A paean of joy rose spontaneously in the heart of every Chicago unionist.

Meanwhile, while these stirring events were transpiring in Chicago, a veritable storm of organization raged in the packing houses all over the country. Strikes broke out in Omaha, Kansas City and Denver. All were successful and left good unions. In St. Joseph, St. Louis, St. Paul, Fort Worth and Oklahoma City the organizers of the Butcher Workmen had remarkable success. Everywhere the workers joined en masse. The movement of the packing house workers was no longer local, but national.

THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT

By the first of November, less than two months after the actual campaign of organization began, the demoralized and “unorganizable” packing house workers had responded so splendidly that the situation was deemed ripe for the unions involved to make a nationwide move for better conditions. Therefore, on November 11th, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen held a national conference in Omaha. They mapped out demands for the eight hour day, substantial increases in wages, equal pay for men and women, etc. This gathering was followed, on November 13th, by a conference in Chicago of representatives of all the international unions most heavily interested in the packing industry, including the Butcher Workmen. This conference adopted practically the same demands as those established at the Omaha meeting. All the organizations pledged themselves to stand loyally together in the big fight looming up.

The next step was to deal with the five big packers—the rest were to be handled later. To this end a committee was appointed, consisting of John Fitzpatrick, President of the Chicago Federation of Labor; Dennis Lane, Secretary-Treasurer of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, and the writer. This committee bearded the autocratic packers in their dens. But it made no progress. The packers refused point blank to have anything to do with the unions. And then, as if to make their refusal the more emphatic, the Libby, McNeill and Libby Co. (a Swift concern) discharged fifty-two men for belonging to the union.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

This at once created a serious situation. For the unions it was a case of fight or die. They chose the former. On Thanksgiving eve a strike vote was put out to all the trades in the nine big packing centers of the Middle West. This carried by a 98 per cent vote, 75,000 packing house workers expressing their determination to strike if no other solution could be found. A telegram was sent to the officials of the A. F. of L. advising them of the action taken. They notified the Department of Labor and a mediator, Fred L. Feick, appeared upon the scene.

Mr. Feick asked that every effort be lent him to prevent a tie-up of the vitally essential packing industry. He proposed that a truce be declared till the Government could look into the situation. This the unions, wishing to cooperate in every way with the Government, readily acceded to, but not until the packers had been compelled to reinstate all the discharged men. Mr. Feick then sought to bring about a meeting between the union committee and the packers. But he failed completely, the packers still maintaining their autocratic position of refusing to give their employes any consideration whatsoever.

A NEW CRISIS

Seeing that the packers paid no attention to the appeals of the Government to settle the trouble peaceably, Mr. Feick left for Washington to report to his superiors. This brought on a fresh crisis for the unions. In a number of recent Chicago strikes Government mediators have intervened, been defied and ridiculed by the employers and have had to pack their grips and depart, leaving the workers infinitely worse off than if the mediators had stayed out of the affair altogether. In such cases the workers naturally conclude that if the Government can do nothing with their autocratic employers it is useless for them to keep up the fight, and a lost strike results. Therefore, when Mr. Feick, following the example of so many other mediator, prepared to leave after his unsuccessful efforts the unions had to act, under penalty of seeing the very ground cut from beneath their feet. They decided that they, too, would go to Washington. They determined to lay the whole matter before the officers of the A. F. of L. for their consideration and action.

A committee was formed. It consisted of representatives of the Illinois Federation of Labor, Chicago Federation of Labor, Stockyards Labor Council, Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, International Brotherhood of Blacksmiths and Helpers, International Brotherhood of Stationary Firemen, International Union of Steam and Operating Engineers, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Brotherhood Railway Carmen of America, International Association of Machinists, United Association of Plumbers and Steam Fitters of the United States and Canada, Coopers’ International Union of North America—these being the principal unions involved in the movement. John Fitzpatrick was chosen spokesman.

The committee went to Washington. A meeting was held with President Gompers and Secretary Morrison of the A. F. of L. These two officers, perceiving the vast importance of the packing house movement, advised that the matter be taken up with Secretary of War Baker. This was done and the situation explained to him in detail. He was told that a strike in the packing houses would probably become general and that no one could set its bounds or be responsible for its outcome. Much impressed Mr. Baker took the matter under advisement. Two days later he wired the President’s Mediation Commission, then in Minneapolis, to go to Chicago and seek a settlement of the difficulty.

AN AGREEMENT REACHED

The Commission hurried to Chicago and began negotiations at once. The unions stated their case, emphasizing their demand for a conference with the packers as the only way to a solution. The Commission did not think this vital, and carried on its work by meeting with each side separately. Following this method two agreements were drawn up, one between the Commission and the unions, the other between the Commission and the packers. The unions signed at 3 o’clock on Christmas morning.

The gist of these agreements was that there should be no strikes or lockouts during the period of the war. All differences between the unions and the packers that they could not settle among themselves should be referred to the administrator, or arbitrator, whose decision should be final and binding. John E. Williams, a man favorably known to Organized Labor in many arbitration proceedings, was chosen administrator. The demands of the unions were to go to arbitration immediately. Things looked rosy for a peaceful settlement. But there’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip.

Meanwhile, Frank P. Walsh, famous as the chairman of the Industrial Relations Commission, came in by invitation of E. N. Nockels, on behalf of the unions, to aid them as an industrial expert in the coming arbitration. Thenceforth to the end he gave them the advantage of his able services without charge. No one acquainted with Mr. Walsh will be surprised at this splendid attitude.

Immediately the administrator took office, on January 2nd, the unions attempted to get the arbitration started. But without success. The packers blocked them at every turn. First, following their original tactics of refusing to meet with the union committee, they insisted that each side be heard alone, the opposing side to know nothing of the argument till several days later when presented with a transcript—a ridiculous proceeding. Then, in flat contradiction of the agreement, they declared that the eight hour question had been settled with the Mediation Commission and could not be arbitrated. They seized upon the most trivial pretexts for delay. And then, as if to show their scorn for the whole situation, they discharged union men right and left. Added to all this there came a sudden and distressing announcement that the administrator had been obliged to resign because of ill-health.

[To be continued.]

From Life and Labor of March 1918, back cover:

—–

Note: Life and Labor is the monthly magazine published at Chicago by the National Women’s Trade Union League of America, Mrs. Raymond Robins, editor.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE & IMAGES

Life and Labor, Volume 8

-Jan to Dec 1918

National Women’s Trade Union League, 1918

https://books.google.com/books?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ

L&L of April 1918

-Life and Labor Cover & WTUL Emblem

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA62-IA1

“How Life Has Been Brought into the Stockyards

A Story of the Reorganization of the Packing Industry”

-by William Z. Foster, Secretary Chicago Stockyards Labor Council

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA63

IMAGE

Life and Labor, Last Page Ad for WZF, WTUL, March 1918

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA62

See also:

The Survey, Volume 40

Survey Associates, 1918

https://books.google.com/books?id=IrRDAQAAMAAJ

Survey of April 13, 1918

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=IrRDAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA33

“Packington Steps Forward” by William L Chenery

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=IrRDAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA35

For more on Chicago Packinghouse Strike of 1904:

-Amalgamated Meat Cutters

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amalgamated_Meat_Cutters

Talking Union – Pete Seeger

Lyrics 1941, by Almanac singers:

-Woody Guthrie, Millard Lampell, Lee Hays, & Pete Seeger