Don’t worry, Fellow Worker,

all we’re going to need

from now on is guts.

-Frank Little

Hellraisers Journal, Friday January 4, 1918

Reprinted from The Masses: Part I-Harold Callender on the I. W. W.

From the International Socialist Review of January 1918:

The Truth About the I. W. W.

By HAROLD CALLENDER

EDITOR’S NOTE: Harold Callender investigated the Bisbee deportations for the National Labor Defense Council. He did it in so judicial and poised and truth-telling a manner that we engaged him to go and find out for us the truth about the I. W. W., and all the other things that are called “I. W. W.” by those who wish to destroy them in the northwest.-The Masses.

[Part I]

—–

—–

ACCORDING to the newspapers, the I. W. W. is engaged in treason and terrorism. The organization is supposed to have caused every forest fire in the West—where, by the way, there have been fewer forest fires this season than ever before. Driving spikes in lumber before it is sent to the sawmill, pinching the fruit in orchards so that it will spoil, crippling the copper, lumber and shipbuilding industries out of spite against the government, are commonly repeated charges against them. It is supposed to be for this reason that the states are being urged to pass stringent laws making their activities and propaganda impossible; or, in the absence of such laws, to encourage the police, soldiers and citizens to raid, lynch and drive them out of the community.

But what are the facts? What are the Industrial Workers of the World really doing? In the lumber camps of the northwest they are trying to force the companies to give them an eight-hour day and such decencies of life as spring cots to sleep on instead of bare boards. In the copper region of Montana they are demanding facilities to enable the men to get out of a mine when the shaft takes fire. It is almost a pity to spoil the melodramatic fiction of the press, but this is the real nature of the activities of the I. W. W.

It is no fiction, however, that they are being raided, lynched, and driven out, without due process of law, and with as little coloring of truth to the accusation of treason as at Bisbee, Ariz., where the alleged “traitors” who were deported were found to be many of them subscribers to the Liberty Bond issue. The truth is simply that the employers have taken advantage of the public susceptibility to alarm and have endeavored to brand as treasonable the legitimate and inevitable demand for better wages, hours and working conditions that has arisen among hitherto unorganized workers. That their efforts are ordinary and legitimate in the trade-union sense, is indicated by the fact,that, as I shall show, unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor thruout the West generally sympathise with and support the struggle of the I. W. W. The old hostility between the two movements has begun largely to be broken down, and the I. W. W., far from being regarded by the working class as criminal or treasonable, has been accepted simply as one of the means of securing their rights.

The case of the lumber camps of the northwestern states is difficult to describe. The two outstanding centers of present conflict, so far as the I. W. W. is concerned, are the forests of Washington, Oregon and Idaho, and the copper mines of Montana. In both places it is a revolt of hitherto unorganized and ruthlessly exploited workers. In both places their demands are for the ordinary wages, hours and conditions which are everywhere recognized by reasonable men as just and inevitable. In both places this revolt has been met with lawless brutality and reckless terrorism on the part of the employers. And in both places the employers have endeavored to cover up their crimes by imputing “treason” to their insurgent employes.

The case of the lumber camps of the northwestern states is one which shows most clearly the origin of the trouble, the nature of the workers’ demands, the methods of the employers, and the fraternization of the I. W. W. and the A. F. of L.

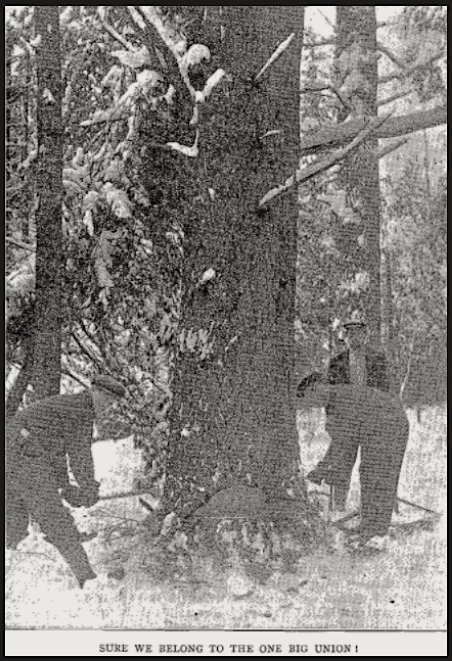

The burden of the struggle in the forests of the northwest is being borne by the Industrial Workers of the World. The new Timber Workers’ Union, an American Federation of Labor body, has enrolled a comparatively small number of the men who work in the woods. But though it is within less than a year that the Industrial Workers have been able to gain wide influence there, they are powerful now, and it is probable that a majority of the lumberjacks and sawmill employes in this region have joined, either as members or as strikers, the Lumber Workers’ Industrial Union. The Timber Workers are all west of the Cascade mountains in Washington. East of the mountains the Industrial Workers have free rein, and west of the mountains there is no rivalry between the two unions at present, both striking for the eight-hour day.

The demands of the Industrial Workers in the forests appear at first glance unbelievable. It is as tho men were striking for a breath of air or a bed to sleep on after a hard day’s work. And indeed they are; asking more windows than the customary two in a “bunk house” that forms sleeping quarters for more than one hundred men, cots with springs and blankets in place of the plain wooden “bunks.” They want, too, places to hang clothing when they go to bed, “drying rooms” so the washed apparel need not hang in the “bunk” house, shower baths (there are no bathing facilities in most of the camps), wholesome food and “no overcrowding at tables.” Fastidious persons, these woodsmen!

The eight-hour day in place of ten hours of work, is the chief issue, but there is insistence on a minimum wage of $60 a month and one day of rest in seven. Which shows what a share in the gains of civilization there is for these men who cut the world’s lumber and float it down the rivers to cities where live the “lumber millionaires.”

It was in the spring that these men began to strike, and by summer most of them had joined the revolt. They congregated in camps of their own in the woods, but were dispersed by sheriffs and soldiers. Some went to the cities, often to be arrested by waiting police. Others sought work on the farms, and found farmers took fright on discovering who they were. Apparently the Industrial Worker was to be denied work on the farms and not allowed to camp in the woods, to induce him to return to lumber cutting.

—–

The Campaign of Lies

What happened at Spokane is illustrative of the systematic attack on the Industrial Workers, who have gained their control of the lumber industry because of the betterment of working conditions brought about by their constant struggles. The West Coast Lumber Men’s Association, aided by its appendages of other employers’ organizations in the northwest, has carried on most of the admirably thoro and successful schemes to develop a popular fear of the Industrial Worker. It is said to have assembled a fund of $500,000 for this express purpose, and it apparently has assembled a part of the military forces of the nation. The newspapers have shown carefully and assiduously that every forest fire was set by Industrial Workers, tho there have been far less forest fires this season than ever before. They have shown that the Industrial Worker’s chief aim in life was to drive spikes in lumber preparatory to sending it to the sawmill, to insert nails in fruit trees and to pinch peaches in the orchards so they would spoil. These things are believed by the people who believe that German spies devote their time to peddling poisoned court-plaster and starting strikes for the eight-hour day. It should be noted in this connection that Secretary Baker asked the lumber companies to grant the eight-hour day because the government needed lumber; and the companies refused. The strike has since spread to the ship-building yards on the Pacific Coast, where the workers have refused to handle lumber cut by men who work ten hours a day. The shingle weavers, both A. F. of L. and I. W. W., are also demanding an eight-hour day.

The lumber strike was directed from Spokane by James Rowan, secretary of the union, and an effort was promptly made to break up the headquarters. Merchants went soberly before the city commissioners and said the Industrial Workers were a menace to the safety of the community. Just why they were dangerous they usually neglected to show, like the Bisbee, Ariz., “Protective League,” which admits there was no violence by the strikers, but is certain there would have been had it not been forestalled by violence by the defenders of copper. They pointed to what had been done in Idaho, where a particularly effective union had closed the lumber industry. They told the city officials that Idaho was boycotting Spokane merchants because they allowed Spokane to harbor the headquarters for the lumber strike. Industrial Workers were expounding syndicalist theories on street corners and the merchants wanted that stopped too. They admitted there was no law under which they could reach this “unlawful” organization, and they were very sorry there wasn’t.

“What you want us to do then,” said one of the commissioners, “is not to arrest them for anything illegal, but just to drive them out of town or suppress them regardless of law.”

The merchants, vague about such details, said that was about it. The city commissioners expressed unwillingness to do any such thing, as there was no disorder. To which the employers responded (not at the public hearing) that that little difficulty might be solved by “starting something.”

But they decided to try to first create a law that would meet the problem. They prepared an ordinance making it unlawful for “any one to publish or circulate1 or say any word * * * expressing disrespect or contempt for or disloyalty to the government, the President, the army or the navy of the United States.” This was so ridiculous that the commissioners would not pass it. Later E. E. Blaine, of the state public service commission, was sent by the governor to Portland to get an order from the commanding officer of the army there directing Major Clement Wilkins at Spokane to arrest the Industrial Workers. Blaine went to Spokane with the order in his pocket.

The absence of some excuse for the action nettled the employers, and they tried to obtain statements by the city and county officials that would warrant military arrests. A meeting was called of the officials and employers, presided over by a lumber dealer. The employers insisted that the local officials sign a statement saying a state of insurrection existed in Spokane. The mayor refused, but the next morning when the merchants went to the city hall with a prepared statement, mild, but good enough as a pretext, and the officials signed it.

This statement says that, while “technically the offenses (of the Industrial Workers) are not against any state or city laws,” still, in order that the Industrial Workers may be curbed in their “unlawful activities” before the community interfered, “regardless of existing laws,” the governor ought to do something that is, the Industrial Workers are law-abiding, but perhaps the citizens who suffer because of their activities won’t be; therefore, the state or the army or somebody ought to stop the whole proceeding by breaking the law and having done with it.

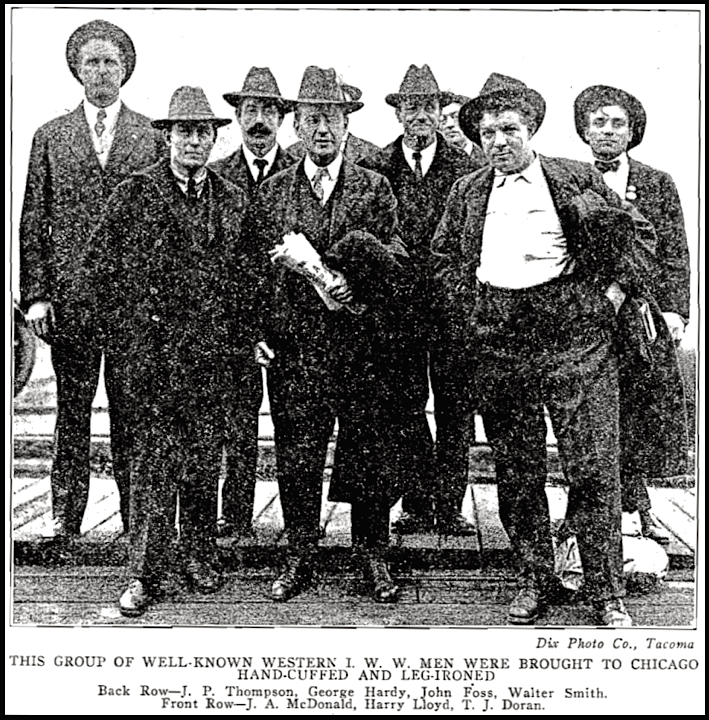

Before this statement had time to reach the governor, the order from the commanding officer was given to Major Wilkins and the headquarters of the Industrial Workers was raided with the arrest of Rowan and twenty-six others by soldiers.

It was lumber dealers who wrote the statement which the city officials signed asking military interference: it was a newspaper man who, at the summons of the soldiers, identified Rowan so they could arrest him!

The Central Labor Council of Spokane in a resolution denounced the resort to military force and called for a general strike as a protest. Soldiers, carrying out the will of the employers’ association, had an ominous appearance to labor. Spokane is typical of the employers’ methods. At Ellensburg, Wash., there is a stockade containing Industrial Workers, guarded by soldiers. But the chief result of such tactics so far has been the spreading of trouble to the Pacific Coast.

—–

The situation at Butte, Mont., where the copper mines have been made idle during a protracted strike, is more complicated. Mention Butte out in the northwest and they’ll tell you, “Oh, well, Butte is a hate town.” It is. It is one of those industrial centers which have undergone the bitter series of hate-generating doses: monopoly control—low wages; forced immigration—lower wages; unionization—bloodshed; higher wages—higher rents. “They get you going and coming,” is the way they put it at Butte (and it was a business man speaking). “The working man doesn’t get even a run for his money in this town.” When one considers Butte and the dark history that portends a dark future, he understands the reason for the extreme degree of bitterness that permeates almost every industrial transaction. The miner knows he has not only in those catacombs 3,000 feet underground, to adhere constantly to the slogan of the boss (typical of the spirit within the industry) “Get the rock in the box”; but that, having got it in for eight hours every day, he must go to his union hall at night and keep the eternal vigil of collective bargaining to be sure that his day’s work brings an income enough to provide for his family. The eight hours’ work is only part of his task. And we wonder at sabotage!

I think that a current witticism, eloquent to the miner, illustrates the spirit bred by “free competition” in the copper mines. One of the chief demands of the strikers is abolition of the so-called “rustling card,” a scheme whereby the blacklisting of workmen is maintained: an applicant for a job fills out a lengthy blank stating his history and political views, then waits ten days or longer while the company verifies it, after which he may get a card certifying his eligibility for employment. When Miss Jeanette Rankin, the representative in Congress, went to Butte to find out about the strike, she was escorted from the railroad station to her hotel by police, in order that the demonstration of welcome planned by the miners might be forestalled. “Miss Rankin should have had a rustling card,” said one of the men.

Immediately after a fire in one of the mines in June, there was planned a public and official memorial in honor of Manus Duggan, whose death at rescue work brought copious eulogies in the newspapers. Arrangements for the memorial were published and everybody thot it quite a proper community action. Then suddenly the whole affair was hushed up, and no memorial has been held. It was discovered at the last moment that Duggan was a Socialist!

It is this intensity of feeling, this clear consciousness of class and class, that rankles in the mind and strips the industrial war of even those thin pretenses that sometimes avail to diminish-apparently—the natural, frank brutality of the battle for sustenance. There is, at least, little actual hypocrisy about it at Butte, save the formal hypocrisy of public statements and newspaper editorials which even the authors admit are bluster. People on both sides speak with a startling candor. Such remarks as this are quite casual and occasion no surprise: “Tom Campbell ought to be hanged, too, along with Little.” Butte has become inured to it.

But the industrial feud is still a tender subject in this mountain town. The outsider, broaching it, feels guilty of an intrusion, as he might if he were to stop a man on the street with, “Say, tell me how you happened to commit that murder.” The town dislikes strikes, just as it dislikes thunderstorms or any other natural calamities; for the strike “hurts business.” That droll humor of the accustomed labor warrior made one of them remark: “This is a city of whispers.” Free speech is not always a matter of constitutional guarantees. What’s the use of a constitution and courts and such embellishments in a region like this? The government, the social relationships, the “civilization” are almost solely economic. If the state were to be deeded, with its people, to the Anaconda Copper Company, things would not be different.

Violence

The wonder is that there is so little violence; the present strike has been entirely free from it, excepting, as they say in Butte, “that lynching.” There have been armed mine guards, those to whom violence is a business that would be destroyed by peaceful strikes. There have been soldiers, but some of them were recalled because they were too unsympathetic with the men working during the strike. There has been instance after instance where absence of bloody clashes seemed to violate the law of sequence. There is the complete background for open war: why it has not come is more than I can tell.

One of the strike leaders tried to explain it. “The men know by experience that it’s no use. They know that what would most please the mining companies would be violence, and they know that they [meaning the enemy] have all the best of it when it comes to that. Why, we haven’t even put out a picket line. I stand up there every morning as the scabs go to work, and count them. Not many can look me in the eye squarely day after day; they turn their heads.”

At the little hall of the Finnish Working Men’s Club on North Wyoming street, headquarters of the Metal Mine Workers’ Union, one finds groups of these men whom even the serfdom of the copper country could not drive to bloodshed. There they assemble, reading typewritten sheets on the bulletin board of official communiques of the war, or chatting about this and that, occasionally about the strike. They have not escaped an air of bitterness, but their extremest imprecations end with vows never to give in, to keep up the strike until their terms are met. And there are 12,000 miners on strike, pinched for resources while they maintain a shutdown of mines that earn for the investors more than a million dollars a day.

I wonder if you and I, or the officials of the copper companies, would remain so mild were we members of the Metal Mine Workers’ Union with families to support, reading statements by our employers that they would flood the mines before recognizing the union. I wonder what would be your mood, you who believe in war, if you were a miner when Ambassador Gerard came to Butte and said, “The laborer must line up with the capitalist”; when owners of these mines scorned your proffer to return to work willingly under government supervision; when they issued a joint statement that “No grievance has been brought to the attention of the mine operators and we believe none exists,” while you knew of the conditions in the mines that allowed 160 men to die in tunnels while flames in a shaft sucked away what air there was: I wonder what, in these circumstances, would come into your mind when, every time you walked down the street, you saw a soiled but distinguishable American flag floating above every shaft on the mountain that is called locally the “richest hill in the world.”

“Fire!”

This strike, now three months old, was one of those unorganized revolts that grow out of copper mountains as pine trees grow out of the neighboring mounds. If there was one tangible cause, it was the disaster at the Speculator Mine, June 8. You may have noticed a small dispatch chronicling the loss of eight score of lives, but you don’t remember it, for such events are commonplaces. “Those poor devils always get caught that way,” remarked a telegraph editor as he tossed the dispatch to a headline writer: “Oh, those damn labor unions,” commented the same keen individual a few days later when the telegraph told of the walkout of the men who dig the copper from the “richest hill in the world.”

After three days of searching, some of the miners were taken from the drifts partly alive and some wholly alive, but there were 160 who were beyond resuscitation. Bodies were piled against concrete bulkheads in the narrow tunnels, fingers worn off by frenzied tearing at the impassible wall. Workmen will tell you at Butte that the foremen didn’t know which passages led to safety, which to death. You see, the concrete bulkheads were erected to protect the mines.

Three of the seven demands, framed at a mass meeting June 12, deal with questions of safety—manholes in bulkheads to allow passage, committees of miners to inspect the workings mouth, every miner to be advised as to ways of escape. The other chief one is for abolition of the rustling card, that autocratic device that has enabled the employers to choke organization of the workmen.

First the strike, then the union: that is the sequence that by its frequency shows the utility of the most elaborate arrangements to maintain individual bargaining. And the strike-breaker of today is the striker of tomorrow; that is the great fact that your short-sighted employer refuses to see. Many of the strikers at Butte are Finns and Italians, imported in past years to replace union men. So with the organized miners in Arizona, who at Bisbee formed a union after they had walked out of the mines. In Colorado, it was the unorganized immigrant of 1903 who became the embattled striker of 1914, after Ludlow.

It has been wise direction as much as spontaneity that has characterized the Butte strike, maintained in face of all manner of attacks and newspaper abuse. It was said that the strike and the new union were products of foreign diplomacy, uprisings against the draft and pacifist maneuvers. The newspapers that grew sentimental over the heroism of the rescue squads that risked lives to reach trapped workmen, now showered calumny on the same men who were seeking to make mines safe. One paper mentioned the “inalienable right of a man to work,” referring not, of course, to the rustling card, but to the few non-union men that stayed in the mines. Women were arrested for distributing pamphlets issued by the union. An effort was made to force grocers to deny credit to strikers and to induce landlords to evict them, as was done at Bisbee, Ariz. The most notable of these intimidations was the hanging of Frank Little by masked men at night. Little, an executive committeeman of the Industrial Workers, had come to ask the new union to join that organization, which it refused to do. [To be continued…]

[Paragraph breaks added.]

SOURCES & IMAGES

International Socialist Review Volume 18

(Chicago, Illinois)

Charles H. Kerr and Company

July 1917-June 1918

https://archive.org/details/ISR-volume18

ISR Jan 1918

https://archive.org/stream/ISR-volume18#page/n165/mode/1up

“The Truth About the I. W. W.” by Harold Callender

https://archive.org/stream/ISR-volume18#page/n171/mode/1up

See also:

Tag: World War I Repression

https://weneverforget.org/tag/world-war-i-repression/

The Masses

(New York, New York)

-Nov & Dec 1917

http://dlib.nyu.edu/themasses/books/masses079

“The Truth About The I. W. W.” by Harold Callender

http://dlib.nyu.edu/themasses/books/masses079/4-5