—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Saturday May 13, 1922

Mary Heaton Vorse on Children’s Crusade for Amnesty

From The Nation of May 10, 1922:

The Children’s Crusade for Amnesty

By MARY HEATON VORSE

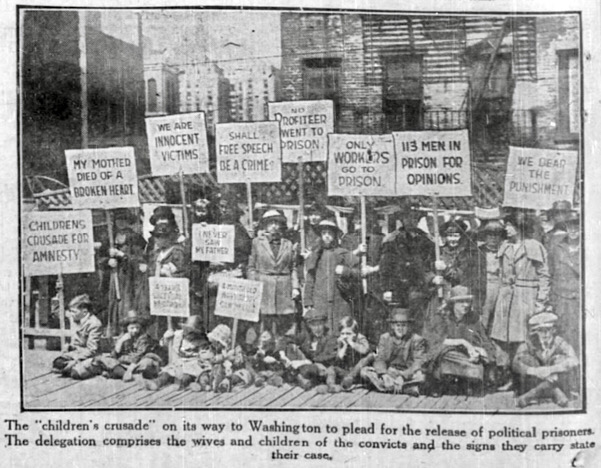

A GROUP of travel-worn working women and their children paraded from the Grand Central Station up Madison Avenue. The young girls stared straight ahead of them; babies stumbled with fatigue. Women, carrying children, sagged along wearily. They carry banners. The little boy who walks on ahead has a firm mouth and holds his head up. His banner reads “A Little Child Shall Lead Them.” There are other banners, which read “A Hundred and Thirteen Men Jailed for Their Opinions”; “Eugene Debs Is Free-Why Not My Daddy?” One banner inquires “Is the Constitution Dead?” One young girl carries a banner, “My Mother Died of Grief.” One woman with a three-year-old baby holds a banner saying “I Never Saw My Daddy.”

Reporters, movie men, and members of the bomb squad accompany the band of women and children. This is a new sort of show. This is a grief parade. These are the wives and children of men serving sentences under the Espionage Act, the wives and children of political prisoners jailed for their opinions. Some of the men did not believe in killing, and some belong to labor organizations. Not one of them was accused of any crime. They are serving sentences from five to twenty years.

Their wives and children are on a crusade. They have come from Kansas corn-fields and from the cotton farms of Oklahoma, from New England mill towns, from small places in the Southwest. They have been through many cities. They are on the way to Washington to see the President of the United States.* They have come here showing their wounds and their humiliation. They have spread out before us their frugal, laborious days. With a terrible bravery they have displayed them so that you and I might see them and be moved—perhaps, and, perhaps, help.

The little procession moves on solemnly. The banners are glittering mirrors held up to you and me—upholders of the Constitution, are you not? Proud of our country’s tradition of freedom. Secure in our belief in the inalienable rights accorded to all men in America. You and I have waited for this quiet silent misery to come forth from its sacred reserve. We have waited, many of us—before we would even write a letter for amnesty—to see the poverty and grief of children displayed on the streets of our cities.

Look at the banners! They say: “Here is our civilization. Look at it. Our women and our children must parade sorrow on the streets to get justice. See these children. Look at their tired faces. This is part of America’s show. Come, folks, look at the sorrow of the children. Men and women of America, look at these reticent mountain women. Look at these shrinking young girls staring straight ahead of them. Look at this home-keeping old mother and these sensitive boys. Look at the tired babies. And realize what desperation has sent them on this crusade through your cities.” These banners have another message for the workers who look at them. It is: “The Constitution is a joke. There are no inalienable rights for workers in America.”

The little procession comes to an end. They reach the Amalgamated Food Workers headquarters. Friends greet them. Chefs from great restaurants have cooked them dinner and waiters have brought them flowers, and gifts for the children. The strained faces of the children relax. The tired women rest. There is one thing that they have gained on this trip that nothing can take from them—the knowledge that they have friends, for some of them have lived in terrible isolation since their husbands and fathers went to jail. A number of the crusaders are women whose husbands belong to the Working Class Union. This union of tenant farmers sprang up spontaneously in the Southwest. The farmers were banded together, hoping through cooperative effort to better their condition. The union grew rapidly and promised to become a power. The interests didn’t like this. The war and the timely Espionage Act furnished a pretext for a round-up. Over a hundred of the most active were arrested. The rank and file were released, the organizers and leaders given long sentences.

These women from mountain villages and their children come of a breed which closes its mouth on grief. Their difficult lives do not allow them such soft habits as the indulgence of tears. One thing they had: they had their privacy. They had the habit of keeping their sorrows inviolate. The proud instinct for seclusion is in the marrow of them. They never came in conflict with the law. They settled their differences between themselves. Understanding this, I want to say to them:

“I know you should have been left to bear the hardships of your lot with your austere dignity. You should have been left to press the firm lips of your determined mouth together in perpetual silence. The decency of your reticence should never have been invaded. I know all this. But the civilization in which we live has made the violation of these sacred things necessary. That is why you left your home. That is why you came on your crusade. That is why I must write, though to put your story into printed words seems a further violation.”

[Mrs. Bryant, the American Woman.]

When I think of what we call the “American Woman” again, it will be of Mrs. Bryant—victorious in the face of poverty, illness, imprisonment. Her triumph is in these words: I put my girls through school.

Mrs. Bryant looks like a tall pine tree, battered by the storm. Like a tree that has had little soil to grow on, but standing on a high place. She has never bent or given to the blows which life has dealt her.

When Mr. Bryant was taken to jail, they were living in a tent in an oil town. It was during the influenza epidemic and every one in the family was sick in bed. The eldest daughter lay dying. George Bryant said: “Don’t feel bad, mother. Anyway, she won’t have to see me go to jail.”

As soon as Mrs. Bryant got out of bed, she made up her mind that the girls were going to go to school—father or no father, jail or no jail. She got a wash-tub, and she got a wash-board, and she washed clothes, and those two girls went to school and they are graduating this year. I have never seen George Bryant, there is one thing I am sure of—that in his jail he is as unbent and as unbroken as that rock of a woman, his wife.

There was another thing that Mrs. Bryant determined to do. She determined to see her husband. Nickel by nickel and dime by dime, with sacrifices that soft people like us do not know about, she saved the price of a ticket to Leavenworth-one hundred dollars. The bank where she kept the money failed. She has not seen her husband.

Somehow I imagine these two silent people have never lost touch. Through the walls of the prison their thoughts meet, for even a free country like ours has found no way yet to jail men’s thoughts. As yet, we only go to jail for thinking. There are many women like her in America.

[The Benefield Family]

The Benefield family live in a high mountain town, a small forgotten place. There are six children. Five are on the crusade. Some soft, kind-hearted woman asked Gene Benefield the sort of question you ask a chubby baby of six. “What do you play when you are home?”

He said: “I pick cotton and I chop cotton.” That is all the Benefield children know about play since their father is in jail—they pick cotton and they chop cotton.

Last year the cotton crop failed. They worked from light until dark and what they made for all the year was $75. They are great, beautiful children, strong and bonny, but they do not smile. They live for themselves. You sense about them the isolation that a jail sentence brings to a family in a little community. They are close together as the fingers of a hand, closed against wounding intrusion like a fist.

[Irene and May Danley.]

Irene Danley carries the banner which reads “My Mother Died of a Broken Heart.”

There isn’t a neighbor around her place who wouldn’t tell you that. There, in the Southwest, there is none of the backing that makes life easier for relatives of political prisoners in the cities. In the country places neighbors whisper and school children jeer at the children of a man in jail. So the mother of the Danley children could not stand the spiritual isolation that walls in the family of a convicted man as surely as the walls surround him and she died of it. Strong sixteen-year-old May Danley came on the crusade, leaving her plow standing in the field—the clay of the furrow still on her shoes. She is working as a farm laborer to support her sisters and brothers.

[Mrs. William Hicks.]

Mrs. William Hicks has tasted quite a few of the advantages of our democracy. Imagine a frail woman, not over five feet tall, who is always ailing. Her preacher husband has been a missionary in India. They were married on his way to America. They drifted to the Southwest. Mr. William Madison Hicks is a descendant of Elias Hicks, the founder of the Quaker Hicksites, and so a pacifist. He did not believe in killing, and this strange aversion caused the gorge of the brave people around him to rise and they dug up a letter which he had written in 1912 to a friend in England, foretelling the war and describing the effect of industry on the American workers. This convicted him.

A month after he was in jail, the baby Helen Keller was born. That made four babies under seven. Mrs. Hicks had to be cared for by the county. The judge took away the next older baby, and when in the courtroom she wept and begged for it he told her she could not have it because she was a county charge and the wife of a convict. So you see, Mrs. Hicks knows a good deal about the benefits of a democracy.

These are some of the stories that Kate O’Hare, their leader, told me as we sat together in the hall of the friendly Food Workers. The great majority of these women know little of the far-reaching conflict of the class struggle. The waiters made an ironic gift to the children-each child got a bank of the Stature of Liberty. But they saw no irony in this. They even sang” My Country ‘Tis of Thee.”

[Mrs. Stanley Clark.]

Kate O’Hare was herself imprisoned for two years in Jefferson City Penitentiary for her opinions. The plan for the crusade started in her office, when Mrs. Stanley Clark and Mrs. Reeder, travel-worn and weary, came in to tell her of their fruitless trip to Washington. Stanley Clark belongs to the Chicago I. W. W. case—that remarkable legal process that will one day be a classic in our history. When the wide net was spread out for the I. W. W. leaders a broad-minded choice was made. No fragile scruples were permitted to interfere with the magnificent course of justice. Dead men as well as living were indicted. They indicted murdered Frank Little. They indicted a man who had been smashed to death on a freight train a year before. They indicted men who had ceased for years to be members of the organization and they indicted men who had never been members. Among these was Stanley Clark, a lawyer, and, although a Socialist, ardently pro-war. His crime was that of collecting money for the families of the Bisbee deportees. Mrs. Clark went to Washington where she was told to get affidavits to support her statements. Through the States of Arizona and Texas Mrs. Clark gathered her testimony. She sent it to Washington. No one knows what has become of it. A waste-basket may have been its fate, or a pigeonhole.

It was hearing this story that made Kate O’Hare think of the crusade. She saw the tired, despairing women before her and she thought of all the women she knew in mill towns and on farms whose petitions have never been heard of, and she thought grimly “These women and children will be a petition that cannot be thrown into a waste-basket.”

I cannot tell all their stories. Of the Reeders, who live in the shadow of Leavenworth jail; of Francis Miller, who inspected half of the cloth for the American Army, but is now serving his ten years because he is an I. W. W. organizer; of gifted Ralph Chaplin, the poet, father of little Ivan [Vonnie], who has been given the savage sentence of twenty years for having once been editor of Solidarity. I do not forget them any more than I forget those other men in jail who have no women or children to march for them; Vincent St. John, for instance, who is serving ten years, although when the Espionage Act was passed he had not been a member of the I. W. W. for years.

[Mrs. Hough.]

I will tell, though, the story of the only mother of a prisoner, Mrs. Hough. She is a little woman and she looks like the ideal picture of “Mother.” She stayed at my house. We talked together homey talk—the common language of women. She told me about her children and I told her about mine and we got to know each other real well, and pretty soon she got telling me about Clyde and her story went like this:

“When the war came, Clyde came to me and said ‘Mother, I’ve been studying over it all night and I made up my mind. I can’t kill any one. I’m not going to register.’ Clyde was brought up in Wisconsin, where people do not believe in killing. This makes a difference to a boy. I said ‘Clyde, you do what you think is right.’ So he went and gave himself up to the jail. And my other son said ‘Mother, I know how you feel about killing, but I’ve got to go.’ I said ‘Son, is this conscientious? If it is, go on.’ And so, one son went to jail and the other went to France, both doing what they thought right. When Clyde was in jail the I. W. W. case came up. Clyde, you know, had belonged to the I. W. W. for a few months. The woodworkers union Clyde belonged to was an I. W. W. organization. He was in jail when the Espionage Act was passed. The day he got out of jail they arrested him. Clyde thought it was an April fool joke—it was the first of April—and even when they took him to Chicago he did not think he was arrested; he thought he was a witness. He was never indicted and he was never tried he couldn’t have conspired, for, you see, he was in jail. Clyde never realized what was happening to him until they sentenced him to five years. He was so sure it wasn’t anything that he even did not take his warm underclothes when he went to Chicago—I had to send them to him. I stood it all right for a long time, but then I got sick and got to thinking about Clyde in the night and I could not stand it and I took to crying. I cried and cried and could not stop crying for days, thinking of my Clyde. It was too much. One boy in France and the other in jail.”

And as I listened to her talking, the same terrible sense of responsibility that had come over me at the sight of those children’s banners came over me again: What have we been doing, the lovers of justice in this country, while Clyde Hough and the others stayed in jail?

[The Angel of Justice.]

The day in New York is over. They stand in a little group waiting in the Pennsylvania Station to make the next station of the cross. Curious people crowd around.

Look at their tired faces, ladies and gentlemen! Look at their scarred hands. Have a glimpse of Mrs. Hough’s grief. Notice Mrs. Hicks, who never smiles. Take another look at Ivan Chaplin. He cries over the poem his father wrote him when he went to jail. It’s an interesting sight, brimming over with human interest. A wonderful spectacle for a fine, free country.

There is a grim Eastern legend that in the hands of the Angel of Justice is a cup, and when this cup is full with tears of children they overflow on the ground and from the place where the tears fall grows a magic tree—a gallows on which to hang the tyrant who caused the tears. This fable has the heart of truth. You may read your history to see if this is so. Ivan Chaplin and the Benefields and the Reeder children have helped to fill the cup here in America.

Maybe the last moment of their stay in New York was a prophecy. One of the children was late. She ran for the train. The door was closed. The Philadelphia Express was leaving.

“Open the gate,” she cried. “It’s a Crusader!” And the gate, that once closed opens for no one, rolled back, and the train stopped.

Perhaps the door of Leavenworth will fly back to the cry “Open! The Crusaders are here!”

* The President was too busy to see them—he was engaged on that day receiving Lord and Lady Astor.-EDITOR.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote Ralph Chaplin, Red Feast, Montreal 1914, Leaves 1917

https://archive.org/stream/whenleavescomeou00chapiala#page/8/mode/2up

The Nation, Volume 114

J.H. Richards, 1922

(search: “childern’s crusade for amnesty”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=dek_AQAAMAAJ

The Nation

(New York, New York)

-May 10, 1922, page 559

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000068744618&view=2up&seq=581

https://archive.org/details/sim_nation_1922-05-10_114_2966/page/559/mode/2up

IMAGE

Childrens Crusade w Signs, Regina Mrn Ldr p16, May 4, 1922

https://www.newspapers.com/image/493675031/

See also:

A Footnote to Folly

Reminiscences of Mary Heaton Vorse

Farrar & Rinehart, 1935

(search: children’s crusade)

https://books.google.com/books?id=sKhAAQAAIAAJ

“Women and Kids Form a ‘Living Petition’ for Free Speech”

https://activistswithattitude.com/women-and-kids-form-a-living-petition-for-free-speech/

American Political Prisoners

Prosecutions Under the Espionage and Sedition Acts

-by Stephen Martin Kohn

Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994

(search with last names mentioned above)

https://books.google.com/books?id=-_xHbn9dtaAC

Tag: Children’s Crusade for Amnesty 1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/childrens-crusade-for-amnesty-1922/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“To My Little Son” by Ralph Chaplin,

Chicago I. W. W. Class War Prisoner

-From Leavenworth New Era, September 9, 1921 https://www.newspapers.com/image/488882936

-Music by Franz Beidel Performance by Arnaud Laborie