—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Monday May 19, 1913

“The Last Day of the Paint Creek Court Martial” by Cora Older, Part II

From The Independent of May 15, 1913:

[Part II of II]

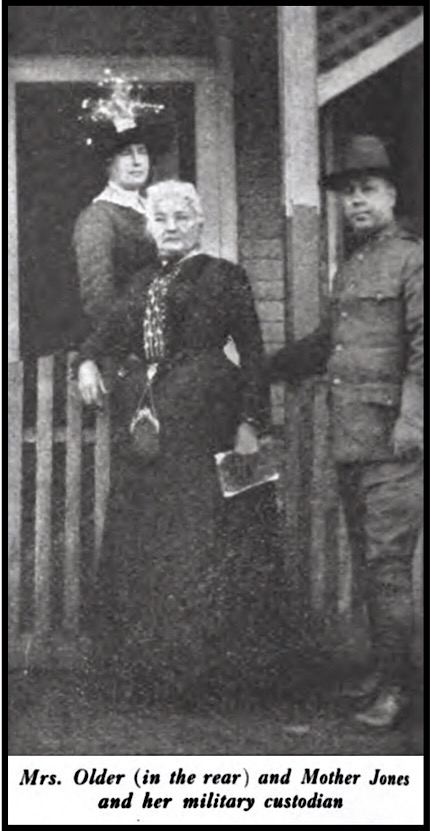

During the recess I had a few minutes’ conversation with Mother Jones. Her eighty years were as nothing—she became a rollicking, irrepressible girl. She liked everyone, even the military court. She told me she was not against the judges, but their jobs. As for the young officer appointed against her wishes her counsel, like an affectionate mother she said, “He’s a nice fellow, only, you know, he’s not my attorney.” She turned to one of the judges who was passing: “Don’t dare find against me. If you do, I’ll——” she shook her fist with a touch revealing coquetry.

When I returned for the evening session, already a crowd had gathered in the street before the court room. Prisoners’ wives with shawls over their heads, leading children, had walked a mile or more. They knew there was no chance to enter the court room, but they stood in the streets, hoping to catch echoes of speeches thru the open windows. One woman flung at a soldier: “Scabs at a dollar and a half a day.” In West Virginia, women fight side by side with men.

Eight or ten sympathizers of the prisoners had already filled the benches in the gas-lit hall. “Everybody’s Dearest Friend” had preceded me. Again he gave me water and a newspaper. The prisoners filed into the room.

“A bad-looking lot of fellows,” he offered.

“Badly dressed,” I answered.

“No, bad men. You ought to know what these miners are. If you had seen and heard what I have.”

A sympathizer with the strikers seated on a bench behind me touched my arm. “Do you know you are talking with Smith, a Burns detective?”

Mr. Smith conferred with the provost marshal, also Associated Press correspondent. Word was sent to the judges’ table. The judge advocate rose and advised all women except me to leave the court room. The women obeyed. A smile played round the lips of Mr. Smith, flirted in the provost marshal’s eyes, and lighted up the table where the judges sat.

The smile died when M. F. Matheny, an attorney for the defendants, rose and said: “These women are friends of the prisoners. They are as much interested in the trial as the men themselves. This man Smith has no right in the court room. He should be excluded if the women are. The court has ruled that no witness after testifying shall remain.”

The court blithely overruled itself and then went on dealing out justice to “criminals.” I was proud to know Mr. Smith. He had invented a new misdemeanor; to mention his name was lèse–Smith. This great court he dominated. William J. Burns was his visible employer. I speculated much about his invisible employer.

I was not to speculate long. An attorney’s speech disclosed that Smith, the gentle overlord of the room, was in the employ of the mine operators. The attorney also revealed that Smith was an excellent detective. He had gone to the strikers, pretended to be in need, had eaten their bread when they had only strike rations. On one occasion his life had been saved by one of the prisoners. The detective had recorded the many violent words uttered and had become chief witness for the state.

While the first speeches were being made, Mr. Smith, the mine operators’ representative, unrebuked by the court, noisily used the telephone. Apparently the judges and Mr. Smith agreed that it was a noble duty to interrupt a dull speech. The prisoners watched Smith with more perturbation than they followed the judges. As the hour grew late, they moistened their lips; their eyes were glassy; even Mother Jones seemed about to faint. Back of Smith was the specter, the guard system, peonage, gatling guns.

Early in the evening the speeches lacked not only power, but sincerity and vision. Yet these last hours were momentous. Not Mother Jones and forty-eight men were on trial, but liberty. For a thousand years civilians had had the right to jury trial. If forty-nine persons could be denied that right, it was in the minds of all that the end of strikes had come and industrial war had begun.

Until M. F. Matheny, of Charleston, spoke, it seemed that the case must go to the judges not only undefended but unargued. He talked briefly of the testimony, which consisted largely of the statement of Smith. He passed quickly to the causes back of the trial, to the crime of low wages, bad living conditions, peonage, the brutal guard system.

Mr. Matheny insisted that the real case had never been before the judges. It could never be tried till the causes that led to the murder were brought into the court room. The death of Bobbitt came from war, industrial war. Armed bands of men had been going up and down the creeks. So long as there was industrial injustice, there would be industrial war. The war was not in the North, South, East or West, but in the mountains of West Virginia. The judges might think they could bring about peace by sending the defendants to prison. They couldn’t. Somewhere else the war would break out. The case would never be settled till it was settled right.

The judge advocate, a tall, slim-necked man, with a high, intellectual head, replied. He pinned his faith to facts. Mr. Matheny was somewhat comic because he talked about causes. What had causes to do with murder? The judge advocate, wearing the uniform that compelled him as a supreme duty to be ready to take life, thought that murder was murder. The judge advocate made an excellent plea for the widow of Bobbitt, and warned the court against confusing causes with facts. At midnight the case went to the judges. The Associated Press correspondent was the only writer present to record what had happened. He was an officer of the court. The longest account of the last day of the trial was a third of a column published the next morning in a Charleston paper.

We followed the prisoners downstairs. A crowd of friends and sympathizers still waited in the dark street. The women ejected from the court room had stood five hours to hear the result. They seemed to consider their ejection a martial law joke, a part of the bitter industrial fight. They waved their hands at the prisoners as they passed on their way to the bull pens. Then the women and children set out on foot for the neighboring towns.

“Halt!” called a picket, flashing a lantern. “Who goes there?”

The women gave their names.

“Advance and be recognized!”

Charleston, West Virginia.

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote Mother Jones fr Military Bastile, Cant Shut Me Up,

-AtR p1, May 10, 1913

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/appeal-to-reason/130510-appealtoreason-w910.pdf

The Independent

(New York, New York)

-May 15, 1913

“The Last Day of the Paint Creek Court Martial”

-by Cora Older

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951000746688i&view=2up&seq=382

https://archive.org/details/sim_independent_1913-05-15_74_3363/page/1084/mode/2up?view=theater

The Independent

(New York, New York)

-Jan-June 1913

(search: “cora older”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=YzQPAQAAIAAJ

IMAGE

Mother Jones, Cora Older, at Military Bastile WV

–Colliers p26, Apr 1913

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000068356118&view=2up&seq=152

See also:

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday May 18, 1913

“The Last Day of the Paint Creek Court Martial” by Cora Older, Part I

Cora Miranda Baggerly Older, 1875-1968

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cora_Baggerly_Older

Tag: West Virginia Court Martial of Mother Jones + 48 of 1913

https://weneverforget.org/tag/west-virginia-court-martial-of-mother-jones-48-of-1913/

Tag: Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912-1913

https://weneverforget.org/tag/paint-creek-cabin-creek-strike-of-1912-1913/

The Court-Martial of Mother Jones

-by Edward M. Steel

University Press of Kentucky, Nov 16, 1995

https://books.google.com/books?id=AbwYuZlwN6UC

In March 1913, labor agitator Mary Harris “Mother” Jones and forty-seven other civilians were tried by a [West Virginia] military court on charges of murder and conspiracy to murder, charges stemming from violence that erupted during the long coal miners’ strike in the Paint Creek and Cabin Creek areas of Kanawha County, West Virginia. Immediately after the trial, some of the convicted defendants received conditional pardons, but Mother Jones and eleven others remained in custody until early May…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Which Side Are You On – Florence Reece & Natalie Merchant