—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday March 12, 1912

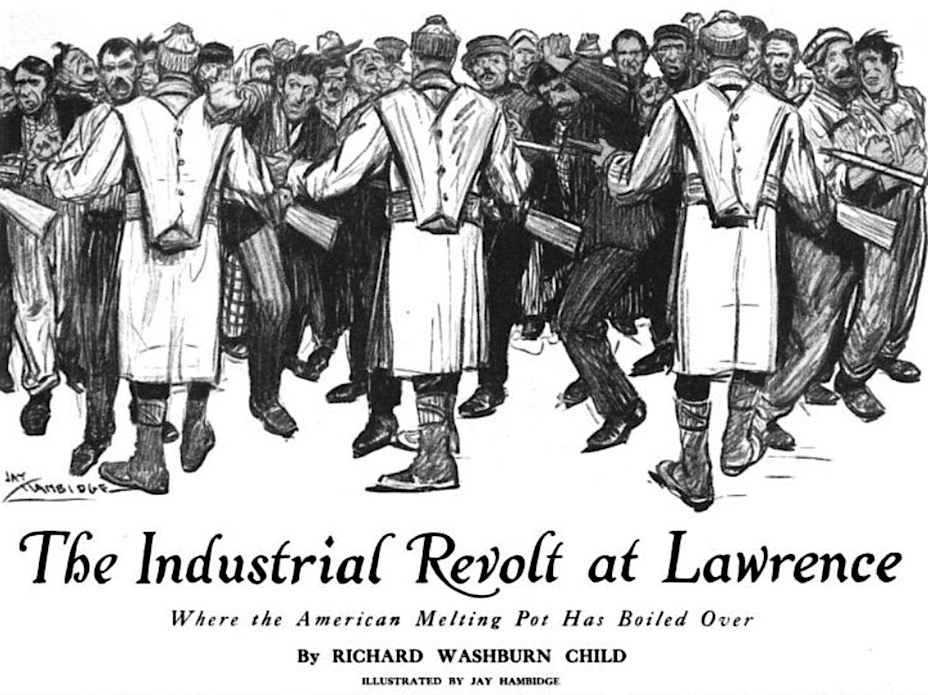

“The Industrial Revolt at Lawrence” by R. W. Child, Illustrated by Jay Hambidge

From Collier’s of March 9, 1912:

———-

DURING these eight weeks in Lawrence, Massachusetts, a strange and wonderful picture has been painted.

Upon the little canvas, woven on the looms of social and industrial development, are now spread the half-somber, half-glaring colors of human instincts and emotions. In the foreground one of our American melting pots, having failed to produce an alloy of many metals, has frothed, sputtered, and boiled over; in the background is the indistinct gray swirl of economic forces rushing by-out of history-into eternity. If there is an awe-inspiring quality in this picture, it is because some day it may be reproduced in great bold strokes across the whole expanse of American life.

Lawrence is drab. In the winter dusk the huge rectangular prisms of the textile mills, black and sullen against the sky line, lie along the shores of the Merrimac River, and, behind them, like a progeny of badly begotten offspring, crowding in a hungry herd, are the countless other rectangular prisms of human habitations.

Systematic and Organized Misrepresentation

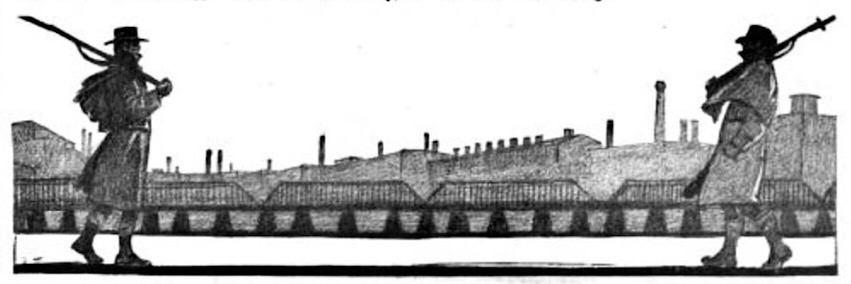

STANDING on a street corner, one sees suddenly that this crowd that moves along the street of shops is a congress of nations. He sees the faces of oppressed peoples, nine-tenths timid and patient, one-tenth of the stuff that makes mobs. The marching feet of a company of soldiers fill the cold, damp air with the grim, scuffling sound of military without music. At every street corner a pacing sentry, who is clad in wool cap, greatcoat, and leggings, lurches back and forth like a huge bird deprived of liberty. His bayonet flashes in the light from the store windows.

“Move on!” said one of them to three men who stopped to cut pipefuls of tobacco on the street corner. He was a boy, and, like the rest, young with the flash of impulse in his eye and unrestraint showing in the youthful fullness of his lips. None the less he stood the torrent of abuse that met his command. “Haven’t I got a right o stand here?” snarled one of the men. “Who are you working for-me or William Wood?” Wood is the financial head of the largest mills.

“Go on now, said the boy threateningly, then turned to the stranger, who was smiling, because he had recognized in the soldier the driver of a laundry cart at home.

“Rotten job,” said he, rubbing his cold ears; “rotten for all of us. Most of us id dead sorry for the strikers. They haven’t done much anyhow. The newspapers have lied about ’em, something’ fierce. There hasn’t been anything much here. The mill men turned the hose on ’em first, that day they broke the windows, and the woman they say was shot by ’em might have been shot by anybody. They’ve paraded down the street. It’s funny to hear that ‘Boo-boo-boo’ they make. It sounds ugly and of course, a gang of ’em might make trouble. But I’ve seen ’em salute the flag as it went by and holler ‘Hooray for de milish!’ at a troop of cavalry. Then if a striker opens an umbrella, it gets into the papers that there’s been a riot. The strikers get the worst of it, but the people of this state are with ’em.”

[…..]

The Picture

I saw with my own eyes, under the gray light that precedes dawn by an hour, a little group of twenty-five women shivering in the cold about the steps of a church.

I saw them pull their shawls over their heads, as they laughed and chatted in low tones. I knew they had assembled to go forth and accost those who would return to the mills to work that morning. I knew this was “picketing,” which, even when peaceful, is unlawful in the Commonwealth.

I saw them stamp their feet because they were cold.

I saw a detail of men come down the street clad in police uniform, with badges gleaming as they passed under the arc light. I heard horses’ hoof upon the pavement. I heard one neigh. A detachment of cavalry was coming up from another direction.

I saw the patrolmen surround the twenty-five women who had huddled and flattened like hens as the shadow of the hawk falls. I heard the voices of men, but no answer from the frightened women. I heard the cavalry men. They were nearer.

I saw the women at the command of the policemen move forward. I heard a rough voice call upon God to damn them.

I saw the night sticks driven hard against the women’s ribs. I heard their low cries as they hurried away.

I saw one who passed me.

“Listen,” she called to a friend. “I go home, I nurse the little one. I be back yet.”

I felt it in my throat. I felt it in my arms. I felt it under the lower eyelids of my eyes. I knew that if that woman had belonged to me, cavalry or no cavalry, I-

There is the terrible thing about a thing like that in Lawrence-that feeling.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote BBH Weave Cloth Bayonets, ISR p538, Mar 1912

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n09-mar-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf

Collier’s

“The National Weekly”

(New York, New York)

-Mar 9, 1912, p13

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008439310&view=2up&seq=990&skin=2021

(search: lawrence richard washburn child)

https://books.google.com/books?id=al8wAQAAMAAJ

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

They’ll Never Keep Us Down – Hazel Dickens