~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Friday October 11, 1907

Old Injunction Judge, John J. Jackson, Passed Away on Labor Day

From the Lincoln, Nebraska, Commoner of September 13, 1907:

THE DEATH of Judge John J. Jackson on Labor Day was a coincidence that was noted by thousands of the older members of American trades unions. Judge Jackson earned the sobriquet of “the iron judge” by reason of his many drastic injunctions against union men. In his anxiety to protect property rights Judge Jackson often lost sight of human rights. It was he who sent “Mother” Jones to jail for daring to make a public address in violation of his injunction, and he enjoined a Methodist preacher from conducting a prayer meeting of striking coal miners in Pennsylvania. At another time he enjoined striking miners from walking the public highways to and from meetings of their local union. The abuse of the injunction writ was forcibly demonstrated by Judge Jackson on many occasions. He was the last of the federal judges appointed by President Lincoln. He resigned a few years ago on account of ill health and advancing age.

———-

[Photograph added.]

From The Fairmont West Virginian of September 6, 1907:

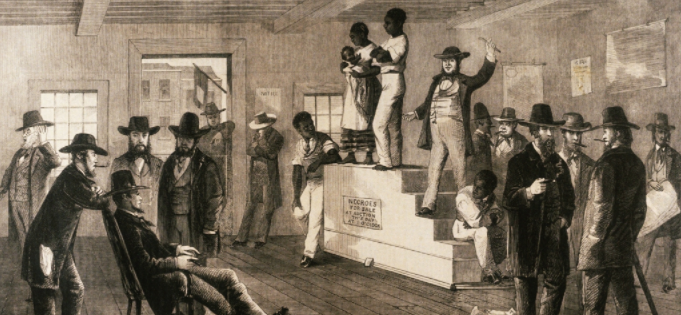

An interesting article, here reprinted from the Chicago Record-Herald of August 3, 1902, provides some insight into the background of the Old Injunction Judge who ruled over the miners of West Virginia with an iron fist from his seat on the Federal Bench in Parkersburg. The Judge came from a family who championed freedom and liberty (for themselves) yet held in bondage, on the family plantation in Old Virginia, human beings as chattel slaves. They loved their slaves, John Jackson had said in 1861, yet loved the Union more. We believe it was Slavery that they loved, not their slaves, for if they truly loved them, as people, they would not have kept them enslaved.

No wonder then that Judge Jackson believed that the wage slaves of West Virginia should have also remained docile and obedient to their Corporate Masters, just as he demanded that those people enslaved by his father should be good and obedient slaves, content with their lot and never over-burdening the Master by rebelling against their enslavement.

ARTICLE IN CHICAGO PAPER

IN YEAR 1902

—–

The following interesting article appeared in the Chicago Record-Herald on August 3, 1902, under Parkersburg date line, and the signature of Walter Wellman, explorer, traveler and journalist:

“All my life I have been opposed to rebellion and revolt against the government. I was opposed to it in 1860; I am opposed to it now.”

So said John Jay Jackson, the patriarchal jurist, “the iron judge,” as they call him here. It was an eloquent appeal for the Union in 1860 that won his judgeship at the hands of Abraham Lincoln. The story of that episode, as I had it from the lips of the venerable judge, is a most interesting one. When the black cloud of secession darkened the nation’s sky in 1860 Mr. Jackson was a young and successful lawyer in his town, then within the borders of Old Virginia. He had graduated at Princeton in 1845, had been prosecuting attorney of his county, and had served three terms in the Virginia Legislature. Like his father before him, he was a Whig-a Henry Clay Whig. He was an elector on the Whig ticket in 1852 and 1856, and in 1800 was chosen a presidential elector when the Ball and Everett ticket carried Virginia. In December of that year he visited Richmond to discharge his duties as a member of the electoral college. The visit gave rise to an incident which changed the whole course of the young lawyer’s career, and came near changing the history of his country.

Judge Jackson is now conspicuous in the public eye as the jurist holds radical views as to the rights of labor agitators to agitate, and as to the punishment which may be properly inflicted upon them. In studying the character of this unique man, now nearly 80 years of age, it is highly interesting to go back to his younger days to see what he was then, to trace out the foundations of his character. This incident at Richmond serves well our purpose.

The citizens of the Virginia capital gave a banquet in honor of the Whig electors. This young lawyer, from what was then called northwest Virginia, was down for a toast. Speakers who preceded him talked little but secession. Lincoln bad been elected, South Carolina was to go out of the Union, southerners feared and detested the regime and abhorred the threatened coercion of sovereign States. The heart of aristocratic, intrepid Virginia was fired with the new idea, and this night it leaped into flame. Speech after speech was made in favor secession. The tide was running strong that way.

—–

When Jackson’s turn came his blood was hot with indignation, but he controlled himself and started calmly. He knew the fierceness of the passion which he had to face, and realized the need of caution. He began with the simile that our sister States could be compared to a family. The family must have a head, responsible and authoritative. It was for the head of the family to issue his orders, to lay his injunctions, for the good of all. If his commands were disobeyed it was his duty to punish. The Federal Government at Washington was the head of the Union family. Every citizen of the republic, every foot of soil was subject to its sovereign will.

“Damn him, he’s in favor of coercion!” cried a rich planter of the other end of the banquet hall. At this a storm of hisses broke, and for a [few?] moments it was doubtful if the audience would permit the speaker to continue. Hisses greeted speaker every word he uttered.

—–

Finally a measure of quiet was restored, and Jackson went on, nothing daunted.

“Would you coerce a sovereign State?” a voice interrupted.

“There is no such thing as a sovereign State,” he retorted. “All the States in this Union are satellites revolving around the central sun, which is the government at Washington.”

Here more hisses filled the air and the banquet hall was in an uproar.

“Would you coerce South Carolina?” yelled a man with a great voice.

“If South Carolina attempted to leave this Union of State, one and inseparable, now and forever,” roared Jackson in reply, “if that child rebels against the authority of the national family, by the Eternal, I’d whip her till she was ready to come back again!”

More hisses, mingled with cries of “Pull him down! Pull him down!”

“I am a Jackson and you can’t pull me down!” was the defiant answer.

This paraphrase of the words of Old Hickory caught the crowd. A latent sentiment in favor of the Union began to express itself and the speaker found he had friends in the audience.

—–

With the tide running his way, the bold young orator shamed bis hearers for their threats to pull him down. “Is this our Virginia?” he asked. “Are you the sons of the cavaliers, gallant and generous? Has it come to this, that a Virginian cannot enjoy freedom of speech before an audience of Virginians?”

He asked them what they of east Virginia had to complain of anyway. Their slaves were secure. They had the fugitive slave law. They lost few slaves, because they had Maryland between them and the North. The county from which he came, up on the Ohio river, had lost more slaves than all of the eastern part of the State. His own father’s plantation had lost more than all the plantations along the James and the Rappahannock.

“The people of my part of the State have uncomplainingly borne our losses,” he declared. “We like our slaves, but we like the Union better. And I say to you here now, that if the State of Virginia secedes from the Union, as sure as there is a God in heaven, northwest Virginia will secede from the State of Virginia!”

Like a bolt of thunder from a clear sky came this declaration, bold and prophetic. It threw the assemblage Into an undescribable uproar. But it set in motion the waves of thought which at one time promised to hold the Old Dominion in the Union. To this day it is believed by many the motion to go out was not fairly carried in the secession convention, but was worked through by a fraudulent count of the votes.

—–

In those days there were few stenographers. Speeches were rarely reported in full. But an imperfect reported of Jackson’s courageous address was printed in the New York Herald. It attracted the attention of Lincoln. Jackson was summoned to Washington and asked to take the United States Judgeship. “You are the man we want and must have,” said Lincoln, “a born Virginian who can make a speech like that at Richmond is the man we need on the bench.” Jackson demurred. He was doing well with his law practice. The salary of the judgeship was only $2,500 a year. He asked two or three days for consideration and while he was considering the President sent his nomination to the Senate and it was confirmed.

Forty-one years ago the 3d inst. Mr. Lincoln signed the commission. Judge Jackson is the senior member of the Federal bench. It is said, and probably with truth, that he has tried more cases than any other man that ever sat in a United States Court. John Marshall and Stephen J. Field sat thirty-four years in the Supreme Court. Judge Jackson is seven years past that mark, and bids fair to be it the harness for many years to come.

—–

“The Iron Judge” has passed through many trying days. He held court throughout the civil war. Soldiers were everywhere,and military authority often clashed with judicial decree. Resistance to the Federal Government was rife, as nearly half of the people sympathized with the Confederacy. At one time the Federal grand jury had 2,000 citizens under indictment. In those days Judge Jackson had a habit of assembling the grand jury before him in the morning and saying to them:

“Gentlemen of the jury, before you start your day’s work permit me to remind you that this union of States is not a rope of sand. Now to you business.”

But with many offenders against the enforcement and other acts he was ever lenient. At one time it was great problem what to do with the convicted persons. There were not jails enough to hold them. Judge Jackson solved it by putting most of the men under bond for good behavior or releasing them on their own recognizance, afterward dismissing the complaints and restoring them to full citizenship.

The old settlers in this valley will tell you that Judge Jackson did more than any other man to keep the West Virginia country in the union and t assuage the bitterness of civil strife.

Though called “the iron judge”-it is undeniable that at times he is exceedingly stern-his heart is soft toward all who show signs of repentance. He would rather reform criminal than to punish him, and it is an axiom among the wrong-doers of this region that a few contrite tears will go very far towards securing a light sentence from the United State District bench. Judge Jackson is fond of lecturing those who come before him. At such moments he is an idealization of Moses, the law-giver. Notwithstanding his nearly four score years, his voice is round and full. He uses it like the natural orator he is.

Those who remember him in his younger days say if he had stuck by the law and politics he would have become one of the most famous orators and public men in the country. Even now the divine fire blazes out when he has a malefactor to sentence. He is an incarnation of the law, moral and statutory. Justice is his watchword, respect for authority his creed. When the trembling creature at the bar hears the old judge roaring at him, shaking the white head and the long finger, he thinks his hour has come. He will be lucky if he escapes hanging and a life sentence is the least he can expect. But the judge’s soul is softened by his own rhetoric. If there is any good at all or promise in the culprit he lets him down easily. If possible he suspends the sentence.

—–

“Mother” Jones and the other labor agitators who fell under Judge Jackson’s contempt could have escaped the jail had they been willing to promise to be good. That was all he wanted a show of contrition, a pledge not to do it again. But they wouldn’t promise. They sat mute. Not believing they had done anything wrong, they were not going to express regrets. With a word they were willing to be martyrized, and the Judge had no recourse but to put them in jail.

One of the agitators, Rice by name, sent from the jail a petition for release. His health was poor, he said, and somewhere out west his wife was dying. He wanted to go home to his family, and would quit agitating. Without a word of inquiry the Judge, his heart touched, ordered this man released. In forty-eight hours Rice was back among the miners, proselyting. My advice to him is to take good care not to get before the judge again.

One funny story of “the Iron Judge’s” softness of heart is told. Probably he has more to do with the moonshiners than any other judge that ever lived. Thousands of illicit distillers and illegal sells of red whiskey have faced him. Years ago the mountains of West Virginia were full of ‘shiners.

Once the Judge was holding court at Charleston. A dozen offenders against the revenue laws were disposed of. Then a woman stood at a the bar. She had a baby in her arms.Her story she told in a simple way. To keep her babe and herself from starvation she had made and sold a a little liquor, but she would never do it again. The judge let her off with a fine suspended the imprisonment, gave her a moral lecture in his classic style, and said he would not send the baby to the penitentiary.

At this moment recess for luncheon was taken, and when court reassembled there was another woman with a baby in her arms. Same result-a light fine and no imprisonment. An hour later a third woman with a baby in her arms faced the court. The keen blue eyes of the patriarchal jurist now opened wide. He called his marshal and ordered an investigation. In a few moments it appeared that the same baby was doing service for all three putative mothers. “If it had not been in court,” says the judge, “I should have had a good laugh. As it was, I had all I could do to keep my face straight.” The were called up. They confessed women their little game ‘twixt smiles and tears. The baby really belonged to the first woman, and she didn’t think it would be so very wrong to lend the child to her friends in distress.

Another lecture from the Judge-a terrible roar, which frightened the wretched women half out of their senses-and three were let off with the promise to give over illicit ‘stilling and the borrowing of babies for the purpose of defeating justice.

“The joke of the thing was irresistible,” says the judge, who has a keen sense of humor, “and, besides, I had declared I would not send that baby to prison.”

—–

This remarkable old man is proud of his physical strength. To this day, like a true Virginian, he rides his horse to and from court, with a “nigger” [we wonder whom the author of the article is quoting here, perhaps Judge Jackson-son of a former owner of human beings] to care for the animal at either end of the route. Some wretched critic had said that he was too old to sit on the bench. Suddenly, one interview, the judge bethought himself of this falsehood. Without a word of warning he seized me and threw me to the other side of the room. The minute I landed there he had me again and tossed me back to the place I had started from.

“There!” he exclaimed, with a smile of exultation, “do you think I am too old and feeble?”

Lawyers tell me that his strength and endurance are extraordinary. Last summer, during the trial of a case in hot weather, he tired out half a dozen of the best lawyers of the State. When at the end of two weeks of dally sessions, they were thinking of asking for a few days of respite the old judge calmly proposed night sessions.

—–

Such is [the] now famous judge of the much talked of contempt cases. Sympathy with that modern industrial and social development, organized labor he has not. This is a thing that has grown up around him and he declines to be a part of it in any way. He can see no reason why labor should organize in West Virginia. His views he comes by through inheritance. His father was a West Pointer, a general, a rich man and slave holder. Men must work to live, and if, he holds, they do not like their wages, there are employers to talk about the matter. With outsiders who come in to organize and agitate he has no patience. A place up in the coal fields where the agitators had a meeting he invariably speaks of as “the spot where the trouble occurred,” just as you would speak in Pennsylvania or Illinois of the place where rioting led to bloodshed. Judge Jackson’s philosophy is summed up in remark which he made to “Mother” Jones when she was before him:

“Is there any reason why you people should not devote all your time and energy to minding your own business?”

But he is a great old judge and a picturesque character for all that.

———-

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

SOURCES

The Commoner

“William J. Bryan, Editor and Proprietor”

(Lincoln, Nebraska)

-Sept 13, 1907

https://www.newspapers.com/image/64181274/

The Fairmont West Virginian

(Fairmont, West Virginia)

-Sept 6, 1907

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86092557/1907-09-06/ed-1/seq-6/

IMAGES

Mother Jones by Bertha Howell (Mrs Mailly), ab 1902

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672082/

Slavery in America, Virginia Auction, 1861

http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery/pictures/slave-trade/illustration

Judge JJ Jackson obit, Huntington Hld IN p2, Sept 3, 1907

https://www.newspapers.com/image/40034757/

Battle Hymn of the Republic – Odetta

“Let the Hero born of woman crush the serpent with his heel.”

Solidarity Forever – UAW

All the world that’s owned by idle drones is

Ours and ours alone.

We have laid the wide foundation built it skyward

Stone by stone

It is ours not to slave in but to master and to own.

For the Union makes us strong.