There are no limits to which

powers of privilege will not go

to keep the workers in slavery.

-Mother Jones

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Thursday December 20, 1906

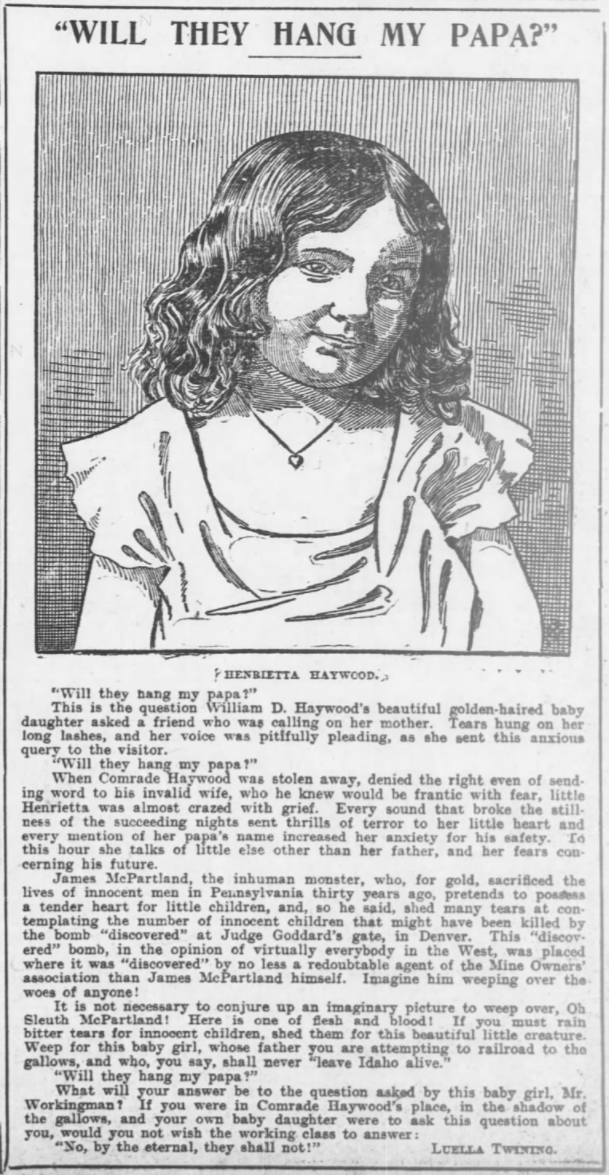

From the Appeal to Reason: The Cry of Big Bill’s Little Daughter

———-

Emma F. Langdon Reports on U. S. Supreme Court Decision

Reporting from Colorado, Mrs. Langdon addresses the recent decision by the U. S. Supreme Court which now makes legal state-sponsored kidnapping in the United States of America. Included in the report is the dissenting opinion of Justice Joseph McKenna.

WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS DENIED.

February 23, 1906, attorneys for the imprisoned men filed petitions in the Supreme Court of Idaho, asking for a writ of habeas corpus to test the validity of the imprisonment. March 12, the Supreme Court refused the writ and remanded the prisoners. March 15, the attorneys for the defense filed petitions for a writ of habeas corpus in the office of the clerk of the United States Circuit Court of Idaho. After several days’ consideration, the writs were refused and the prisoners remanded. A bill of exceptions was filed, and an appeal was taken to the United States Supreme Court. The decision of the Supreme Court, handed down Monday, December 3, 1906, fully ten months after the men had been kidnapped from Colorado, sustained those of the lower Federal and Idaho state courts. This meant the legalization of kidnapping, an act heretofore considered a crime, by the highest judicial authority in the land.

If the reader will read the synopsis of Justice Harlan’s opinion there can be but one impression left in the mind—that the constitutional laws are but hollow mockeries when the working men of the land test them to obtain their rights under the so-called laws of this Republic. Others will find as time puts them to the test that the constitution of our state or nation has not during the past few years and will not in the future, so long as monied interests predominates over justice, come to the rescue of any but the monied power unless, perchance, it suits the convenience of the corporate power that controls the executive, legislative and judicial departments of government of state or nation. A decision such as Justice Harlan’s should be sufficient cause to shatter the reverence felt in the past for the judiciary, when it is so plainly shown they are but the willing tools of corporations to put the stamp of legal approval upon the lawlessness of the trusts and monopolies of various kinds.

Through the decision of Justice Harlan, the United States Supreme Court said to the world: “We approve of kidnapping.” According to the decision, kidnapping is legal if perpetrated by the governors of two states, who have entered into a plot with a corporation, to seize in the midnight hour, the victims and spirit them away to another state, in which they have not lived, and confine them in a felon’s cell. If this is not a violation of the constitution of the United States then let it be amended in such a manner as to make it a crime. If the governors can do this legally, in what manner would private citizens offend if they should follow the example of the executives of the state? Does kidnapping become legal only when indulged in by the governors? Are men who are clothed with executive authority licensed through the positions they hold to mock laws and jeer at the lauded rights we are told are guaranteed by a constitution. Synopsis of the Supreme Court decision follows:

SYNOPSIS OF SUPREME COURT’S DECISION.

Looking first at what was alleged to have occurred in Colorado touching the arrest of the petitioner and his deportation from that state, we do not perceive that anything done there, however hastily or inconsiderately done, can be adjudged to be in violation of the constitutional laws of the United States.

He added that the governor of that state had not been under compulsion to demand proof beyond that contained in the extradition papers. His failure to require independent proof of that fact that petitioner was, as alleged, fugitive from justice, can not be regarded as an infringement of any right of the petitioner under the constitution or laws of the United States. He also said that even if there was fraud in the method of removal there had been no violation of rights under the constitution.

It is true, as contended by the petitioner, that if he was not a fugitive from justice within the meaning of the constitution, no warrant for his arrest could have been legally issued by the governor of Colorado, It is equally true that after the issuing of such a warrant before his deportation from Colorado it was competent for a court, Federal or State, sitting in that state, to inquire whether he was in fact a fugitive from justice, and if found not to be, to discharge him from the custody of the Idaho agent and prevent his deportation from Colorado.

WHERE IDAHO WINS.

No obligation was imposed by the constitution or the laws of the United States upon the agent of Idaho so to time the arrest of the petitioner and so to conduct his deportation from Colorado as to afford him a convenient opportunity before some judicial tribunal sitting in Colorado to test the question whether he was a fugitive from justice and as such liable, under the act of Congress, to be conveyed to Idaho, for trial there.

It can not be contended the the circuit court, sitting in Idaho, could rightfully discharge the petitioner upon the allegation and proof simply that he did not commit the crime of murder charged against him. His guilt or innocence of that charge is within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Idaho state court. The question in the court below was not whether the accused was guilty or innocent, but whether the Idaho court could properly be prevented from proceeding in the trial of that issue upon proof being made in the Circuit Court of the United States sitting in that state, that the petitioner was not a fugitive from justice and not liable, in virtue of the constitution and laws of the United States, to arrest in Colorado under the warrant of its governor and carried into Idaho.

HARLAN’S SUMMING UP.

In summing up his lengthy opinion, Justice Harlan says:

Even were it conceded, for the purpose of this case, that the governor of Idaho wrongfully issued his requisition and that the governor of Colorado erred in honoring it and issuing his warrant of arrest, the vital fact remains that Pettibone is held by Idaho in actual custody for trial under indictment charging him with crime against its laws, and he seeks the aid of the circuit court to relieve from custody so that he may leave that state. In the present case it is not necessary to go behind the indictment and inquire as to how it happened that he came within the reach of the process of the Idaho court, in which the indictment is pending, and any investigation as to the motives which induced action by the governor of Colorado and Idaho would be improper as well as irrelevant as to the real question to be now determined. It must be conclusively presumed that those officers proceeded throughout this affair with no evil purpose and with no other motive than to enforce the law. The decision of the lower court is therefore affirmed.

This decision caused little surprise. In this age, where corporate interests predominate over justice and right and the constitution is ignored, when it suits the interest of capital, it is not strange that the Supreme Court of the United States should have sustained the lower courts, regardless of the rights of the masses.

Justice McKenna had the courage to hand down a dissenting opinion. This opinion was, undoubtedly, such a one as would have unanimously been rendered by the United States Supreme Court if the personnel of said court were true to the constitution of these United States and were concerned in safeguarding the interests of the masses, rather than subservient to the interests of a favored class.

McKENNA’S DISSENTING OPINION.

Justice McKenna’s magnificent dissenting opinion follows:

I am constrained to dissent from the opinion and judgment of the court. The principle announced, as I understand it, is that “a circuit court of the United States, when asked upon habeas corpus to discharge a person held in actual custody by a state for trial in one of its courts under an indictment charging a crime against its laws, cannot properly take into account the methods whereby the state obtained such custody.”

In other words, and to illuminate the principle by the light of the facts in this case (facts, I mean, as alleged, and which we must assume to be true for the purpose of our discussion), that the officers of one state may falsely represent that a person was personally present in the state and committed a crime there, and had fled from its justice, may arrest such person and take him from another state, the officers of the latter knowing of the false accusation and conniving in and aiding its purpose, thereby depriving him of an opportunity to appeal to the courts; and that such person cannot invoke the rights guaranteed to him by the constitution and statutes of the United States in the state to which he is taken. And this, it is said, is supported by the cases of Kerr vs. Illinois (119 U. S. 436), and Mahon vs. Justice (127 U. S. 700). These cases, extreme as they are, do not justify, in my judgment, the conclusions deduced from them. In neither case was the state the actor in the wrongs that brought within its confines the accused person.

In the case at bar the states, through their officers, are the offenders. They, by an illegal exertion of power, deprived the accused of a constitutional right. The distinction is important to be observed. It finds expression in Mahon vs. Justice. But it does not need emphasizing. Kidnapping is a crime, pure and simple. It is difficult to accomplish; hazardous at every step. All the officers of the law are supposed to be on guard against it. All of the officers of the law may be invoked against it. But how is it when the law becomes the kidnapper?

When the officers of the law, using its forms and exerting its power, become abductors? This is not a distinction without a difference—another form of the crime of kidnapping distinguished only from that committed by an individual by circumstances. If a state may say to one within her borders and upon whom her process is served, I will not inquire how you came here; I must execute my laws and remit you to proceedings against those who have wronged you, may she so plead against her own offenses? May she claim that by mere physical presence within her borders an accused person is within her jurisdiction denuded of his constitutional rights, though he has been brought there by her violence?

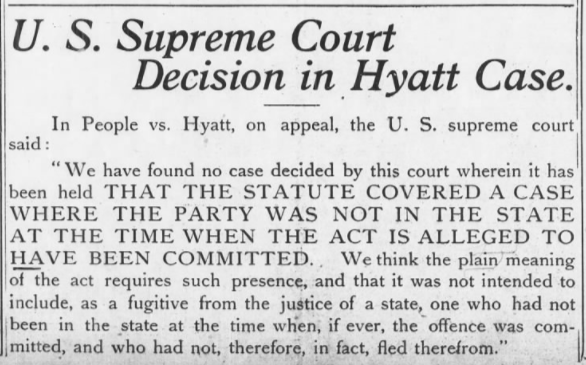

And constitutional rights the accused in this case certainly did have, and valuable ones. The foundation of extradition between the states is that the accused should be a fugitive from justice from the demanding state, and he may challenge the fact by habeas corpus immediately upon arrest. If he refute the fact he cannot be removed (Hyatt vs. Corkran, 198 U. S. 691), and the right to resist removal is not a right of asylum. To call it so, in the state where the accused is, is misleading. It is the right to be free from molestation. It is the right of personal liberty in its most complete sense; and this right was vindicated in Hyatt vs. Corkran and the fiction of a constructive presence in a state and a constructive flight from a constructive presence rejected.

This decision illustrates at once the value of the right, and the value of the means to enforce the right. It is to be hoped that our criminal jurisprudence will not need for its efficient administration the destruction of either the right or means to enforce it. The decision, in the case at bar, as I view it, brings us perilously near both results. Is this exaggeration? What are the facts in the case at bar as alleged in the petition, and which it is conceded must be assumed to be true? The complaint, which was the foundation of the extradition proceedings, charged against the accused the crime of murder on the 30th of December, 1905, at Caldwell, in the county of Canyon, state of Idaho, by killing one Frank Steunenberg, by throwing an explosive bomb at and against his person. The accused avers in his petition that he had not been in the state of Idaho in any way, shape or form, for a period of more than ten years, prior to the acts of which he complained, and that the governor of Idaho knew accused had not been in the state the day the murder was committed, “nor at any time near that day.”

A conspiracy is alleged between the governor of the state of Idaho and his advisers, and that the governor of the state of Colorado took part in the conspiracy, the purpose of which was “to avoid the constitution of the United States and the act of Congress made in pursuance thereof; and to prevent the accused from asserting his constitutional right under clause 2, section 2, of article IV, of the constitution of the United States and the act made pursuant thereof.” The manner in which the alleged conspiracy had been executed was set out in detail. It was in effect that the agent of the state of Idaho arrived in Denver, Thursday, February 15, 1906, but it was agreed between him and the officers of Colorado that the arrest of the accused should not be made until some time in the night of Saturday, after business hours—after the courts had closed and judges and lawyers had departed to their homes; that the arrest should be kept a secret, and the body of the accused should be clandestinely hurried out of the state of Colorado with all possible speed, without the knowledge of his friends or his counsel; that he was at the usual place of business during Thursday, Friday and Saturday; but no attempt was made to arrest him until 11:30 o’clock p. m. Saturday, when his house was surrounded and he was arrested. Moyer was arrested under the same circumstances at 8:45, and he and accused thrown into the county jail of the City and County of Denver.

It is further alleged that, in pursuance of the conspiracy, between the hours of 5 and 6 o’clock on Sunday morning, February 18th, the officers of the state, and “certain armed guards, being a part of the forces of the militia of the state of Colorado,” provided a special train for the purpose of forcibly removing him from the state of Colorado; and, between said hours, he was forcibly placed on said train and removed with all possible speed to the state of Idaho; that prior to his removal and at all times after his incarceration in the jail at Denver he requested to be allowed to communicate with his friends and his counsel and his family, and the privilege was absolutely denied him. The train, it is alleged, made no stop at any considerable station, but proceeded at great and unusual speed, and that he was accompanied by and surrounded with armed guards, members of the state militia of Colorado, under the orders and directions of the adjutant general of the state. I submit that the facts in this case are different in kind and transcend in consequences those in the cases of Ker vs. Illinois and Mahon vs. Justice, and differ from and transcend them as the power of a state transcends the power of an individual.

No individual could have accomplished what the power of the two states accomplished. No individual or individuals could have commanded the means and success could have made two arrests of prominent citizens by invading their homes; could have commanded the resources of jails, armed guards and special trains; could have successfully timed all acts to prevent inquiry and judicial interference. The accused, as soon as he could have done so, submitted his rights to the consideration of the courts. He could not have done so in Colorado. He could not have done so on the way from Colorado. At the first instant that the state of Idaho relaxed its restraining power he invoked the aid of habeas corpus successively of the Supreme Court of the state and of the Circuit Court of the United States. He should not have been dismissed from court, and the action of the Circuit Court in so doing should be reversed.

[Photograph added.]

SOURCES

Appeal to Reason

(Girard, Kansas)

-Dec 15, 1906

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67586773/

The Cripple Creek Strike

-by Emma Florence Langdon

Denver, April 1908

http://www.rebelgraphics.org/wfmhall/langdon00.html

Haywood-Moyer-Pettibone Case

http://www.rebelgraphics.org/wfmhall/langdon29.html#dedication

“Writ of Habeas Corpus Denied”

http://www.rebelgraphics.org/wfmhall/langdon29.html#writofhabeascorpusdenied

IMAGES

HMP, Henrietta by Twining, AtR, Dec 15, 1906

& HMP, US Sp Crt Hyatt, AtR, Dec 15, 1906

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67586773/

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: U. S. Supreme Court Rules Against Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone in Habeas Corpus Cases

https://weneverforget.org/hellraisers-journal-u-s-supreme-court-rules-against-moyer-haywood-and-pettibone-in-habeas-corpus-cases/

Are They Going to Hang My Papa?

Performed by John Larsen and Michelle Groves

Lyrics by Owen Spendthrift, 1907

http://steunenberg.blogspot.com/2009_08_01_archive.html