When they fired the tents of Ludlow,

They lighted fires in the hearts of the workers

They can never put out.

-James P Thompson

Hellraisers Journal, Monday January 28, 1918

From the International Socialist Review: Class-Struggle Unionism

Industrial Unionism:

What It IsBy JAMES P. THOMPSON

[Part II.]

You will find one class owns the means of production and another class operate them. The interests of these two classes are diametrically opposed. The interest of the employing class demands that we work hard for small pay. Our interest demands that we put the other class to work. Today, we not only have to feed ourselves, but we have to feed an idle, worthless class who have no more function in society than a bedbug. Now, in order that you may fully understand this, you have asked me in this letter to me, when subpoenaing me, to mention the lumber industry. And I will explain the psychology of the lumber worker.

I think, altho I am a longshore man—I am one of those undesirables who travel everywhere, not to simply stir up people, but to tell people what we believe can be done to make this a better world. Now, the logger, he walks out in the woods and looks around at a wilderness of trees. He works hard in there. And what does he get? He gets wages that are below the dead line. I say dead line in wages means below the line necessary to keep him alive. They are being murdered on the installment plan.

Now, they breathe bad air in the camps. That ruins their lungs. They eat bad food. That ruins their stomachs. These foul conditions shorten their lives and make their short lives miserable. When they ask for more, like the I. W. W. did-we asked for dry rooms so we could have a place to dry our clothes. If we don’t dry our clothes—I have got a bad cold, it bothers my throat—if we don’t have—that is all right, I don’t want any water, thank you. You know it rains very much, now, speaking of this particular part of the country, which I always like to apologize for doing, as this is a world question, I am only using this as an example, in this part of the country, for example, it rains a great deal and they work in the rain. If they didn’t work in the rain they wouldn’t work at all.

When they come in from the camps, they are wet, their feet are wet. They go into a dark barn, not as good as where the horses are, and the only place to dry their clothes is around the hot stove made hot to dry the clothes. Those in the top bunks suffer from the heat, those far away from the cold. Well, if they don’t dry their clothes they put them on wet the next morning. Then they would have rheumatism. And when we asked for dry rooms in which to dry our clothes, a man like Weyerhaueser, who owns all this land here as far as your eye can reach—or as far as a mind’s eye can reach, almost. Oh, no, he can’t afford to put in dry rooms. No. Why not. Well, business is business.

And so the logger, he finds that he is nothing but a living machine, not even treated as well as a horse. When the horse is out of work he is glad of it. When the wage worker is out of work he is up against it, they turn the hose on him in Sacramento. All right. Now to show you just how we look at this. We say that in the early days a man came into this western country—this is only an example of the western country—when land was cheap, and when politicians could be bought two for a nickel—that is the way we put it in our language, understand—they got possession of this land, like Morgan and those fellows of the so-called better class, you know, that bribe legislators, as in the New Haven Railroad proposition you know about. They got out here and by bribing and grafting and gunning and one thing and another, they got possession of this land, this forest out here. And then they say to us:

“You came too late. We own this land.” Where did they get it? We know where they got it, they stole it. But they say: “We have a legal right,” and all that stuff, a law they made themselves. Now, just to show you how we look at it, because that is the vital point, you know, you are talking now with a revolutionist. I believe I have the psychology of a revolutionist. And we look at that as just as ridiculous as it would be as if suppose we would go out into the forest, and we would see a lot of squirrels out there working hard gathering nuts. Then in the winter we would go out there and we would see the nuts piled high, and these same working squirrels in misery. We would say to them, “What is the matter?” “Why,” they would say, “Don’t you know what is the matter ? Why, those fat squirrels over there they never worked and they own all this forest here, and when we produce the nuts we turn all the nuts over to those fat squirrels. And then they have a lot of little clerks to sort out the wormy nuts, and on pay day they give us our snuff and our overalls and our hob-nailed boots—” the way the worker puts it, the squirrel would get the wormy nuts.

We claim that no man has more right to own this earth than he has to own the air he breathes; that John D. Rockefeller has no more right to say: “I own that coal mine, I own the coal down in the earth as far as hell.” You don’t have to go very far in a coal mine to get to hell. You are in hell if you are in a coal mine, especially if it is Rockefeller’s coal mine, because he murders more in proportion to the number than any other in the country. We say they have no right to own this. Right is a relative term. They will own it just as long as they have the power to own it. And just the minute that we get the power we will do away with this thing of some human beings owning the things that other human beings must use in order to live.

And now I will become a real American again. Abraham Lincoln said, “the government of the people, by the people, for the people.” Well, that is tame compared to the I. W. W., and our idea will prevail when those who are opposing it are forgotten. I believe that, as much as that I am sitting here. We are the modern abolitionists fighting against wage slavery. Here is one of our sayings: “The industries must be owned by the people, operated by the people for the people, instead of being owned by the few, operated by the many for the few.” And in regard to the social unrest, it is not the degree of exploitation as much as it is the fact of exploitation.

If we remain in this room for many days we would learn more about the room as we remained. We would know that it was warmer in one corner, and more cool in another. And so with society, the longer we live in this capitalist society the more we learn about it. We have learned that the capitalist papers, as we call them, will lie, that they will lie—well, will lie about the I. W. W., see. And so, as the result of the lying, and suggestions and misrepresentations on the part of the press, the workers are losing confidence. You know we used to say in this country that a thing was true, and prove it was, by saying we saw it in black and white. Well, a man that would try to prove a thing by saying he saw it in black and white in some of the papers in this country now, would be considered a candidate for the insane asylum.

And so with the courts. Now, we are losing confidence in the law. We have but very little confidence, I am speaking frankly of the working class all over the country and to those of the world this applies to a more or less extent. The country most developed industrially will furnish to the more backward countries the image of their own future. Now, we are gradually losing respect for the law, because it is universally expressed in this way, there is one law for the rich and another law for the poor. Everyone, generally speaking, will admit that if you steal a loaf of bread you go to jail; if you steal a railroad, you go to Congress. Now, that is the way they express that idea.

Now, the other class attempts to hold our class down by high-handed methods, like the hop-pickers’ case. When you go to California you will hear about the hop-pickers’ case. Two men are in jail sentenced to life imprisonment. They didn’t kill any one. Everybody admits they didn’t kill anybody. They were telling the workers in that hop ranch what they thought ought to be done. There was no drinking water there. Every way the conditions were unspeakable. I won’t take up your time with that, I expect you will get all of that in California. But those two men are in jail. Now, it doesn’t matter what you mean is this, that going from one end of the country to the other, any working man who knows anything about it believes those men are innocent, and every day they are in jail—every day they are in jail, just like rust eats iron—so confidence in the capitalists’ courts is dying in the hearts of the workers.

Now, they can be high-handed, like in Ludlow. They can fire the tents there, and they did. And you have heard the old saying, “the shot is heard around the world.” When they fired the tents of Ludlow, they lighted fires in the hearts of the workers they can never put out. We are not patriotic like we used to be, in the sense that we will fight for the other class to get markets. We do not take any stock in this foreign market business at all. The world’s market for steel, the workers of the world produce the steel, and no matter whether the railroad is built in China or in England, it matters not to us as a class. We do the work, and all we get is what? As the wealth piles up on the one hand, misery piles up on the other, and the working class see this. They know that labor produced all the wealth.

Now, this puts it so any child can understand it. You know we form habits of thought. Now, we workers know that if our class wasn’t here on earth at all, the other class would have to go to work. We know that well enough. If our class was not here on earth and the other class wanted shoes, for instance, they would have to go ahead and make them, and if they didn’t know how to make them, they would have to learn how or go barefoot. Now, the difference between what we produce and what we get is the amount of which we are robbed. All capital is unpaid labor.

Now, there are two armies in some countries in the world, the army of production and the army of destruction. The army of destruction is the military army, that is it is one of them. Now, the army of production feeds everybody. They produce it all, and what we want is for the army of destruction to disband, and join the army of production, and then we who do the work won’t have to work so hard, won’t have to work so long. We will have the world’s work to do, but we will have more help to do it, and then we won’t have the capitalist class that class that says: “We own the earth and the machinery of production.” We want to put them to work and make them do their share. In other words, we want to do away with the wage system and establish the co-operative system in its place.

The labor process has taken the co-operative form and the things that are used collectively must be owned collectively. And this class struggle will never end until the workers of the world organize as a class, and take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.

Counsel: Now, Mr. Thompson, assuming that we were all in accord with your ideas, your philosophy of industry, taking society as it is today, formed of people with various views, with the majority not, perhaps, agreeing with your theories of production, what would you say to this Commission that it could do, either by recommendation to Congress, to the various state governments, or to the workers—the people of the country, that would probably be accepted and would lead towards this newer society that you are speaking of?

Answer: Well, since you put it so broadly that you recommend to all the different ones what to do: Now, I would say to the government, for instance (to put it that way; I look upon them as a committee of the capitalist class. But the government, political government, not the real ruling government of the country; I don’t mean that, I mean the political government.) I mean that I would recommend to this Commission that they say to the representatives—to all whom it may concern—that the cause of social unrest is to be found in the mode of production, that a revolution is inevitable, that we may delay that revolution a little, we may hurry it a little, but we can’t stop it, and that everyone who is big enough to rise above local interests and see the inevitable, should do all in their power to lessen the birth pangs of the new society being born from the womb of the old. And to the capitalist class, I would say to them: “You are doomed. The best thing you can do is to look for a soft place to fall.”

Counsel: That, Mr. Thompson, then, would be your practical suggestions to this Commission? Answer. I would absolutely think that that would save—if the ruling class of today were big enough to that, I believe it would save much misery in the world.

Council: I don’t mean that, Mr. Thompson. I mean your idea of what can be accomplished. Answer: I lost one point. You asked me what I would recommend to the working people?

Counsel: Yes. Answer. All right. We would recommend to the working class that they organize as a class and depend for their labor laws, not on the politician, but that they should organize and pass the labor laws in the union, and enforce them on the job. We are unlike the editor of the Seattle Record of the A. F. of L. He says they, the A. F. of L., issue a paper. You asked him what the purpose of that union paper was, and he said—if I remember rightly, he said it was to teach the workers their rights under the law and to get them to work for the passage of better laws. Now, our idea of a labor paper is that it should teach the foolishness of going to these politicians to get these laws, and that they should pass the law in the union and enforce it on the job. If you wanted to do away with child labor, organize and refuse to work with children.

Counsel: Any other practical suggestions, Mr. Thompson? Answer: I believe that the way to do away with the unemployed is this: Now, I mentioned a moment ago that there are two armies, the army of production and the army to destruction. I include the capitalists in that, because when they eat it is destruction of property. When the workingman eats, it is in a sense productive consumption, like a locomotive eating coal. So, I say this: That-I don’t mean that literally—that it is real productive consumption when I say the workman eats, I don’t mean in the literal sense, but I mean it in one sense; but in regard to this army of production and the army of destruction I want to use an illustration that I think will make clear the cause and cure for unemployment.

Now, we will take the army of destruction in an enemy’s country. Suppose that there is only a certain amount of food to eat, and it is all in the form of bread; suppose that when we come to see that army of soldiers, the army of destruction, we see that they have nothing to eat but bread, but that one part of the army got eight or ten loaves every day, and the other part of the army had no bread at all. We would think they were crazy. We would say put that army on rations; give each five loaves, or whatever is necessary so it will go around. Now, we walk away from them, and we see the army of destruction; they do not live on bread—they do and they don’t—they must have labor in order to live. Well, we see that some of that army get eight, ten, or twelve hours labor, and the others have none at all—well, what would we do?

The same as with the bread. Now, we divide the bread among the soldiers, and so we should divide—now notice—we should divide the work of the world among the workers of the world. Then, when we do that, there will be no unemployment. If there is not work enough for all of us all the time, there must be work enough for all of us part of the time. The idea of some working ten hours and others having no work at all, that is out of date—ridiculous. The idea of little children being worked to death while strong men are out of work, no one but a savage will support that in our opinion. So we believe that we ought to shorten the work day, divide the work of the world among the workers of the world, and then there would be no unemployment. Then, the other class, in their struggle with us, would find it hard to get scabs, they would find it hard to get men to eat food that we had refused to eat, as there wouldn’t be any unemployed to draw from.

Well, when we get the unemployed out of the hands of the other class, the main club would be out of their hands, and then we would make the boss, we would force the boss to pay us more wages for five or six hours than he does now for eight and ten. That is not all. When we have divided the work among the workers of the world, then we have gotten the bosses around on the slippery end of the stick. Then we will put them to work, and this system will be over, and we will establish the co-operative system. That is revolutionary, but that is what we are after.

[Paragraph breaks added.]

SOURCE

International Socialist Review Volume 18

(Chicago, Illinois)

Charles H. Kerr and Company

July 1917-June 1918

https://archive.org/details/ISR-volume18

ISR Jan 1918

https://archive.org/stream/ISR-volume18#page/n165/mode/1up

James P Thompson on Industrial Unionism

-also source for image of Thompson.

https://archive.org/stream/ISR-volume18#page/n188/mode/1up

See also:

James P. Thompson

http://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/pamphlets/25years/25thompson.html

Commission on Industrial Relations

-Fifth of Eleven Volumes of Testimony

4097-5086: Volume 5

https://books.google.com/books?id=z-ceAQAAMAAJ

4190: Seattle, Wash., Wednesday, August 12, 1914—10 a. m.

Present: Commissioners Commons (acting chairman), Lennon, Garretson, and O’Connell; also W. O. Thompson, counsel.

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=z-ceAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA4190

4217: Afternoon Session

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=z-ceAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA4217

4233: Testimony of Mr. James P. Thompson

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=z-ceAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA4233

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday January 31, 1917

Washington, D. C. – Government Printing Office Publishes Reports

Published! 10,000 Copies of Eleven-Volume Sets of Testimony Submitted to Congress by Commission on Industrial Relations

Hellraisers Journal, Saturday April 21, 1917

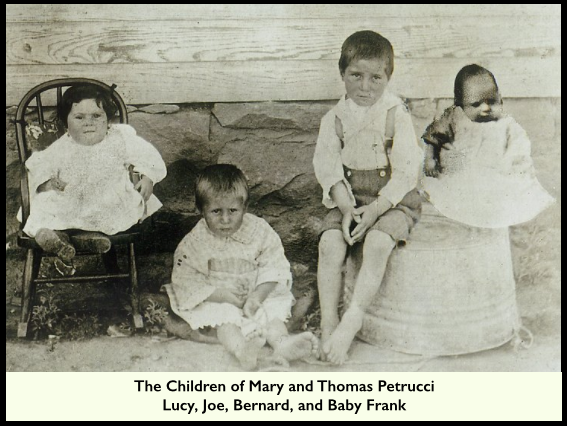

Remembering Ludlow: Mrs. Petrucci’s Story of Grief and Sorrow

Remembering Ludlow: Mary Petrucci fled burning tent as militia fired upon her and her children.

WE NEVER FORGET