—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday March 17, 1912

“The Trouble at Lawrence” by Mary Heaton Vorse

From Harper’s Weekly of March 16, 1912:

A few weeks ago a company of about forty children of the Lawrence strikers, bound for Philadelphia, were forcibly prevented from leaving Lawrence by the order of City Marshal John J. Sullivan. He was led to this act by the belief that some of those children were leaving town without the consent of their parents. Before this, several groups of children, to the total of nearly three hundred, had been sent out of town to the strike sympathizers in various cities, and public opinion against the departure of the children had been aroused. As Congressman Ames said: “The people here feel that the sending away of these children has hurt the fair name of Lawrence since it is a rich town and capable of caring for all its needy children without the help of outsiders.”

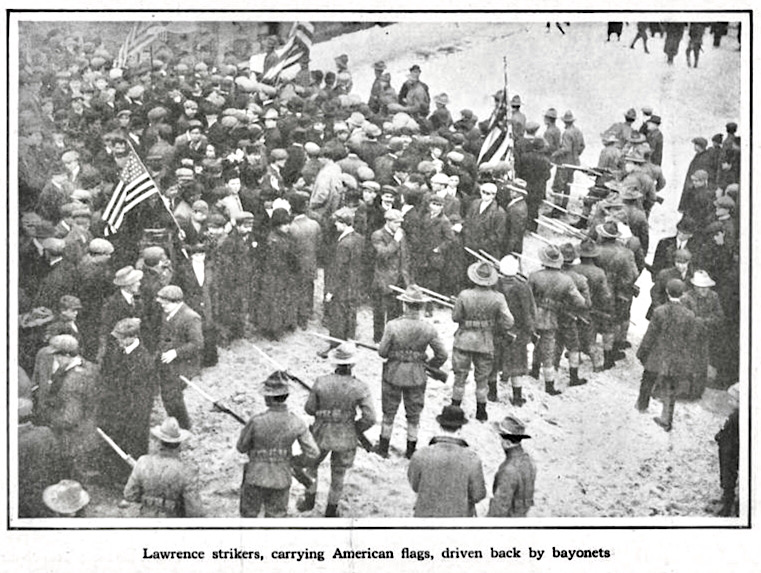

The forcible detention of these children had an extraordinary response throughout the country. It was one of those things that cannot be done in America without stirring up public opinion from north to south and east to west. There had been earlier aggressive moves on the part of the authorities: Joseph J. Ettor, one of the first to take charge of the strike on behalf of the Industrial Workers of the World, and Arturo Giovannitti, his chief lieutenant, were arrested and committed to jail without bail, as accessories to the murder of a woman [Anna LoPizzo], shot by a deflected bullet during a clash between the strikers and the police. Both men were two miles away during the conflict. Their imprisonment caused comment in the press, as did other episodes of the strike- for instance, the railroading of twenty-three men to prison for one year each, during a single morning’s police-court session, on the charge of inciting to riot; but in the minds of the country at large these things have been simply incidents. The abridgment of the right of people to move from one place to another freely was at once a matter of national importance. It had for its immediate sequel the sending of that touching little band of thirteen children of various nationalities to Washington to state their grievances and to testify as to what occurred at the railway station on that Saturday morning.

This was the culminating incident in a strike which has been an extraordinary one throughout, and which, throughout, has been diversified with incidents of an unusual kind.

It is an eloquent little commentary on the wage scale of Lawrence that the passing of the beneficent fifty-four-hour bill should have been the indirect cause of the strike. This bill limited the work of women and children in Massachusetts to that number of hours a week, and the mills of Lawrence could not run fifty-six hours for their men alone. Therefore they cut the hours to fifty-four as the laws demanded, and at the same time, cut the pay by 3.57 percent. It is also claimed that the mills speeded up the work. January 13th was the last payday before the strike, and a few days later the mills were no longer making cloth.

In the present-day labor situation, as every one knows, strikes are prearranged, and, on a certain given day, the people walk out; but the strike of the textile workers in Lawrence was the spontaneous expression of discontent of a people whose scant wages, averaging between $5 and $6 a week, were cut below the living point. They went out, over 25,000 of them, of all crafts, without organization and without strike demands. They had no leaders and they themselves were composed of all the peoples of the earth, and were of warring nations and warring creeds. In this extraordinary fashion did the strike begin.

At the same time the mill hands went out, the American Federation of Labor had a membership, according to John P. Golden, president of the Textile Union of New England, of approximately 250, and the Industrial Workers of the World a membership of about 280. The American Federation of Labor has not recognized the strike. Apparently this organization was annoyed that the strikers had not played according to the rules of Hoyle laid down by their organization. It was not their strike, neither was it the strike of the Industrial Workers of the World. The strike was merely the indignant expression of people who considered that their wages had been cut below the living point.

The I. W. W. took immediate steps to bring some order out of the chaos in which the workers were plunged. William D. Haywood, Ettor, and Giovanitti began to organize all of the textile workers into one great industrial union. They enrolled the majority of the 25,000 strikers, men, women, and children, in the I. W. W. They formulated demands for a flat increase in wages of 15 percent, a fifty-four-hour week, double time for overtime, the abolition of the premium or speeding-up system, and no discrimination against those who were on strike. Arrayed against the strikers, along with the mill owners, the militia, and the police, were the officials of the Textile Union of New England and the Central Labor Union of Lawrence. The American Federation of Labor at Washington was also hostile, seeing in the ideal of labor solidarity that was being preached at Lawrence an attack on craft unionism. But it was a message. which appealed strongly to the diverse mass of men and women who made up the strikers, and it held them. After Ettor’s arrest the task of welding the alien groups into one fell upon the shoulders of Haywood, and the release of Ettor and Giovanitti was added to the demands.

As a contrast to the action against Ettor, it is interesting to cite this incident. John Ramay [Ramey], a young Syrian of nineteen, went out on the morning of the 29th of January at six o’clock. He joined a crowd of strikers which the militia moved along. He was at the back of the crowd. At fifteen minutes past six he was brought into his mother’s house with a bayonet wound in the back and he died at seven that night. The name of the militiaman who killed Ramay is unknown, nor has any action been taken against him. He was not held for murder nor complicity of murder as it was decided that he was within his rights.

Lawrence is in atmosphere a New England city. It has about 88,000 inhabitants, of which 60,000 are mill workers and their families. Thirty thousand of these people work in the mills, and it is said that over thirty-three dialects are spoken in this New England town and that of full American stock there are not more than 8,000 while 45,000 alone are of English-speaking nations.

The town sits in a basin surrounded by hills. Along one side of it runs the Merrimack River, wide and shining. If you approach Lawrence from South Lawrence you must pass through acre after acre of mill buildings and mill yards until you reach the wide waterway whose sides are factory-bordered, whose surface mirrors the monotonous pale-red brick of factory wall and factory chimney.

If you walk down Essex Street, the principal business street, and glance to your right and then to your left, you will receive an impression of always seeing at the end of the street on the one hand a little church steeple spring upward and on the other an imposing mill chimney. The ever-recurring little church steeples of Lawrence give one the impression of the children of a dying race; the big smokestacks are the young giants of a new, red-blooded generation.

From one end to the other of Lawrence run the mills, most of them situated on a piece of made land between the Merrimack and the canal. The mills are Lawrence; you cannot escape them; the smoke of them fills the sky. The great mills of Lawrence make the Lawrence skyline; they dominate and dwarf the churches. From Union Street to Broadway along the canal the mills stretch, a solid wall of brick and wide-paned glass, imposing by their vastness and almost beautiful, as anything is that without pretense is adapted absolutely to its own end. The mills seem like some strange fortress of industry, connected as they are by a series of bridges and separated by a canal from the town.

In the Syrian quarter, beautiful long-eyed Syrian women, their hair down their backs, sat Oriental fashion on meager cushions on the floor nursing pale babies in rooms where it was almost dark, although outside the day was bright and clear and snow sparkled on the ground. A typical family of this sort is that of a certain woman in an alley tenement of Oak Street. There were six in the family, which lived in three rooms. The halls were dirty and full of ashes and unremoved garbage. The family was supported by the work of children-a boy of sixteen and one-half years and a girl of seventeen, who earned between them $12.50 a week. The rent was $10 a month. It was this girl who cried, in the tone of one who would say-“Oh, that one would give me to drink of the water that flows” : “Oh, that only we had never come away from Damascus!” And one had a picture of these people who were so beautiful to look on in their own home, the sun at least about them. As a Syrian said apropos of the killing of Ramay, when Haywood cautioned his compatriots to moderation and patience, “If we have not much law in our country, at least we have satisfaction!”

It is in homes like these that one would find the posters of the Wood mills, representing long lines of the mills on the one hand and a happy band of workers with their full dinner pails proceeding to work on the other. These posters and the representations of agents caused many workers to come to this country.

It is only by chance that I have mentioned the Syrians; their case is of course that of all the other workers.

The Jewish strike delegate, an impressive man with a worn face, said he had a wife and eight children who were all too young to work in the mills. When he was asked how much he averaged he replied, I’m ashamed to tell you!” They paid $2.25 a week for their tenement, and when he was asked if he took lodgers he replied in a matter-of-fact tone, “Why, of course, how else could I live?” Five of his children were among those who were being taken care of in New York and other cities.

The different nationalities keep together and have their own meeting places, from the substantial brick Turn Verein building of the Germans to the tiny Lithuanian church.

There are quarters of the town where you may not hear a word of English spoken. I have been in Italian towns where I have heard more American-English spoken on the streets by returned emigrants than I did in the narrow streets and alleys and Valley Street. The picture show notices were in Italian; goats’ cheese and salami hung up in the windows; women with shawls on their heads went in to buy meager stores of their day’s marketing; and windows of the stores held colored posters which represented the glorious victories of the Italians over the Turks.

This is the town, so New England in setting and surroundings, so mixed in its nationalities-this town whose great mills are the latest expression of our tremendous industrial development-a development which has created a situation which no one as yet fully understands in all its complexity, with which our state government cannot cope, and which has caught in its tangled web the people who are the very creators of the situation itself.

The strike of Lawrence involves the questions of emigration and of the tariff, of the ability of a state with a fifty-four-hour law to compete with a state whose workers have two extra working hours: the effect on the country at large of a working community which habitually lives under conditions which do not make for healthy children.

Lawrence is a small town: there are 20,000 people there who, whatever else happens, can never again have the race hatreds and creed prejudices that they did before they had learned what working together may mean. They have learned, too, the value of organization and their one executive ability has been developed, for they have had to feed a great company of people and administer the use of the strike funds. Young girls have had executive positions. Men and women who have known nothing but work in the home and mill have developed a larger social consciousness. A strike like this makes people think. Almost every day for weeks people of every one of these nations have gone to their crowded meetings and listened to the speakers and have discussed these questions afterward, and in the morning the women have resumed their duty on the picket lines and the working together for what they believed was a common good.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote BBH Weave Cloth Bayonets, ISR p538, Mar 1912

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n09-mar-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf

Harper’s Weekly

(New York, New York)

-Mar 16, 1912, p10

(search: lawrence vorse)

https://books.google.com/books?id=lU4TlSVvdZoC

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015033848121&view=2up&seq=296

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

“The Lawrence Strike” by Mary Heaton Vorse

Published: A Footnote to Folly: Reminiscences of Mary Heaton Vorse, Farrar & Rhinehart, 1935.

Transcribed: for marxists.org in January, 2002.

https://www.marxists.org/subject/women/authors/vorse/lawrence.html

Part III:

Lawrence was a singing strike. The workers sang everywhere: at the picket line, at the soup kitchens, at the relief stations, at the strike meetings. Always there was singing.

In many different places over the United States, workers’ songs have been written and sung. Many of them are anonymous. Other song writers stand out, like Ella May Wiggins of Gastonia, who was shot and killed during the strike in 1929, and Aunt Molly Jackson of Kentucky, whose songs will be sung as long as there are miners.

In Lawrence the excitement of achievement was everywhere. We found that men and women who until yesterday had known only the routine of the mill had worked out large-sized organizational jobs in the commissary, organizing relief, collecting and distributing food, running their own finances. The Lawrence strike had six stores and seven soup kitchens and maintained a large force of relief workers. The workers organized their mass demonstrations and mass amusements, huge picnics and concerts.

Over all, and including all the strike activities, was the sense that the other workers were with them. Most workers, especially the unorganized, lived isolated lives, spent between the job in the factory and a tenement home and the saloon. They knew only the people in their own department in the mill. Suddenly, in strike time, the working force became a unit. Workers realized that the mill was like a single person. Not only that, but the workers in all the many different mills, who had never known each other, who at most had seen each other’s faces hurrying past on the street, now, under strike conditions, were united. All at once they were living, marching, singing, listening to one mighty rhythm, the workers’ solidarity. Their mass feeling had magnified their powers and lifted them above isolation and poverty.

Not only were the workers united, but there was no moment of the strike when the workers were not conscious of the other workers throughout the country, whose eyes were fixed on their struggle. Strike funds arrived daily from other unions in the industry and other sympathetic unions. Delegations of workers came to visit. Speakers came, and for a moment in Lawrence speakers, visitors, spectators, strikers, leaders were outside themselves, swept up out of their small personal existences into the larger and august flow of the strike.

There at Lawrence it seemed sometimes as though the forces of Light and of Darkness were visibly divided. On one side the workers, simple, kind and transformed with the faith that the realization of solidarity gave them; on the other, the greed of the employers, who roused up gangs against the workers and who paid to have dynamite planted for the purpose of blackening the workers’ cause.

No one could see these singing, disciplined people without being moved by them. A spiritual quality that was felt by everyone showed itself at the strike meetings. Ray Stannard Baker said, “It had a peculiar, tense, vital spirit that I never saw before in a strike.”

Something very good was being evolved here. People were thinking in unison. People were acting in unison. Marching together, singing together. Harmony, not disorder, was being established, yet it was a collective harmony. A meeting like this was the antithesis of mob; people coming together to build and create instead of to hate and destroy. What we saw in Lawrence affected us so profoundly that this moment of time in Lawrence changed life for us.

Both Joe O’Brien and I had come a long road to get to Lawrence. It was for us our point of intersection. Together we experienced the realization of the human cost of our industrial life. Something transforming had happened to both of us. We knew now where we belonged — on the side of the workers and not with the comfortable people among whom we were born. We knew, although at the time our personal lives seemed incidental, that we wanted to go on together and work together.

Some synthesis had taken place between my life and that of the workers, some peculiar change which would never again permit me to look with indifference on the fact that riches for the few were made by the misery of the many.

It was in Lawrence that we realized what we must do, that we could make one contribution — that of writing the workers’ story — as long as we lived. We did not work this all out immediately, but a great and important change in the motivation of our lives had occurred.

We realized, too, that all the laws made for the betterment of workers’ lives have their origin with the workers. Hours are shortened, wages go up, conditions are better-only if the workers protest. We wanted to work with them and write about them. We wanted to break through the silence and isolation which surrounded the workers’ lives until everyone understood the conditions under which cloth was made, as we had been made aware.

I have tried to account for what happened to us both in Lawrence. The sense of indignation which we shared was not the whole story. It was far more complex than that. It was seeing of what beauty human beings are capable. Here in Lawrence was the flame; that surging forward toward the light which is the distinction of mankind.

That striving for light appears in many different forms. It has demanded religious freedom, freedom of scientific thought, political freedom. In our generation it is striving toward economic justice. It is this that sings our songs, makes the art and discoveries of a race and shakes off age-old tyrannies.

The flame ebbs; it fluctuates. It never goes out. It appears now in a Steinmetz or an Einstein. Now in the spontaneous uprising of the textile workers in Lawrence, now in the great paintings of Rivera and Orozco. In this flame resides the genius of a people.

It is this flame that leads forlorn hopes, that wins victories against incredible odds–faith, courage and beauty are its texture. When people are gathered together, when the individual is forgotten for the collective good, there is this quickening. Suddenly the aspirations of once anonymous lonely people who have come together form the flame.

We felt this more strongly every day we were in Lawrence and as we began to know the individuals in the strike. We would go with Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Tresca to an Italian dinner at Rosa Cardello’s. Haywood and the other organizers bought the spaghetti and salad and Rosa prepared it. At that time Haywood ate as often as possible in the workers’ homes because mobs of hoodlums prowled the streets to “get” him. Always behind him went an Italian bodyguard. His self-constituted guards even slept in his room. Hoodlum gangs always shadowing the leaders were forerunners of the Committees of a Hundred who wrecked the workers’ strike headquarters in Gastonia and Charlotte, or the Citizens’ Committees who have attacked the workers in California, or the Vigilantes who have attacked agricultural workers’ unions in Ohio and New Jersey.

The gangster fights which have become a feature of certain city strikes, notably in the needle and building trades, were completely absent in Lawrence. It was an innocent strike, yet it had an explosive quality. A peculiar rhythm was evolved here. The excitement which streamed from the men and women and children was heard from one end of the country to the other.

When we went home Italian guards walked with us. They wouldn’t let us go home alone. Whenever we went around at night there were always Italian boys following us. We got to know not only Italians, but Slovaks, Greeks and Syrians.

In the Syrian quarter, a young Syrian named John Ramey had gone out one morning to go to the store for his mother. He was merely a boy who stayed home, not an active striker. I don’t think he had ever been on a picket line. He got in with a group of strikers who were going down the street. The militia told them to move on. A quarter of an hour after John Ramey went out he came back with a wound through his back where he had been prodded with a bayonet. He died that night. Nothing was ever done about it. No one was ever convicted or even brought to trial, but it made the Syrians very bitter.

One snowy night a number of us were having dinner in a Syrian restaurant. I had been up to see Ramey’s mother, who was glad to tell the story to reporters. Haywood was there and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, William Allen White, the Fremont Olders [Fremont and Cora Older], Gertrude Marvin and some other reporters. The proprietor would not let us pay for our dinner, would only accept some money for strike funds.

A militiaman walked up and down provocatively in front of our quiet restaurant. There was no reason why this quiet place should have been patrolled. We were leaving, with only the small delays that a rather large party causes, when the militiaman told us roughly to “Keep on moving!” One of our party remonstrated with him and asked what we were doing. We were “congregating,” he said.

“Come on, come on,” Haywood said hastily. “For God’s sake, get out of here, don’t give back talk to the guard.” We looked back. The Syrian restaurant keeper stood a short way behind our group, a long knife in his hand. We hurried off in silence.

Time after time the anger of the people would boil up, but in some way Haywood and the other leaders would manage to calm them and to keep them disciplined.

Joe O’Brien came from the South and had a Southerner’s instinct toward direct action. He suggested that Haywood retaliate. Haywood put his hand on Joe’s shoulder.

“My boy,” he said, “you can’t exchange brickbats for bullets. You can’t exchange bullets for machine guns. The most violent thing a striker can do is to put his hands in his pockets and keep them there.”

The fire of the strike was like a beacon light. People of all sorts streamed through Lawrence. Lincoln Steffens, Fremont Older, William Allen White, Richard Washburn Child, Ray Stannard Baker, were only a few of the people who came to write about it. A peculiar fusion occurred among those who met here. Lifelong friendships began at the Lawrence strike. Vida Scudder spoke to the workers and made her famous speech in which she said: “I would rather never again wear a thread of woolen than know my garments had been woven at the cost of such misery as I have seen and known past the shadow of a doubt to have existed in this town . . . . If the wages are of necessity below the standard to maintain man and woman in decency and in health, then the woolen industry has not a present right to exist in Massachusetts.”

The papers suppressed her speech or printed only garbled accounts. People demanded that she be dismissed from Wellesley for these revolutionary utterances. Yet in the workers’ press the speech rang from one end of the country to the other. It stirred the torpid social conscience of Massachusetts.

Ray Stannard Baker prophesied that the Socialist party might yet become the great conservative party of this country, as a bulwark, of course, against a revolutionary movement like that of the I.W.W. He found some of the mill masters in Lawrence “almost shivering with the astonishingly new idea that it might be a good policy to tie up with the trade union movement in order to fight the encroachments of this new and revolutionary industrial unionism.”

Of all the outsiders, the most interesting to me was a woman doctor [Elizabeth Shapleigh?]. She had come down to Lawrence in the beginning of the strike and decided to move her practice there. She had made a study of the tubercular curve of children who had worked in the mills from the age of fourteen to twenty-four and had compared it with the tubercular curve of all Massachusetts children of the same age. There was a shocking difference.

Lawrence children’s tubercular curve mounted in a straight line. There were hundreds of victims every year and, she added, from largely preventable causes. She said that she was very lonely in Lawrence because none of the people of her own kind would have anything to do with her. She was a pariah because she had identified herself with the workers. It seemed to me that the decent people, who were like those I had lived with all my life, were indifferent only because they were ignorant of the conditions under which the Lawrence workers lived, as I had been ignorant.

If they knew the cost in lives, if they knew that one child in every five died before it was five years old, if they knew the overcrowding, if they saw that tubercular curve, they must know at last what the people were striking about; not outside agitators, but against death and privation.

Armed with this information, I did a series of interviews. I saw the principal men of the town and all the ministers and several prominent women. Not one was interested. Everyone met me with stony disapproval. The best they could say of the workers was that they were misguided people led astray by outside agitators, that they were pigs and preferred to live as they did to save money.

I did not then recognize this reaction as the inevitable reaction of the owning group protecting itself instinctively against any vital workers’ movement. Twenty years later, nice women in Kentucky told me identical things about the miners.

I tried to find some of the principal stockholders. The best names in New England figured as large holders of stock, Coolidges, Amorys, Aldrichs, but not a one of them lived in Lawrence. It was entirely an absentee ownership.

Meantime the craft unions sabotaged the strike by trying to call off the strike of the crafts.

It is interesting to reflect that the syndicalist movement which made all America tremble a quarter of a century ago lives today only in shrunken form in France and Spain. History proved in Italy and in Germany that you cannot build “a new society within the shell of the old.”

The Lawrence strike was making too great a commotion. Ever larger numbers of people were drawn within its circle. It affected all the workers of the country. It caused a Senate investigation. It was evident that Schedule K, the tariff on wool which was supposed to protect the workers, had done nothing for them. On the floor of the House it was said that “Bayonets and decreased wages for the workers, instead of the Workers’ Paradise predicted by Aldrich, Lodge and Smoot, is the definition of Schedule K.”

The strike was moreover affecting the bond issue being floated by the American Woolen Company. The women of New England who invested in textiles had been listening to the words of Vida Scudder. There was a pressure of public opinion to settle the strike with gains for the workers.

In March the strike was settled with a sliding scale of from ten per cent to five per cent; ten per cent going to those least paid. It meant sixty or seventy cents more a week in pay envelopes. The strike cost $1,125,000, according to the New York World; the militia had cost the taxpayers $125,000, but the workers’ pay rolls had been raised six million dollars throughout New England and thousands of workers were affected besides the victorious Lawrence strikers.

Twenty-three years have passed since the Lawrence strike. Empires have fallen, yet the injustices in the textile industry which made that strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 are in broad outlines as true today as they were then, except that today we have the added horror of the speed-up.

Twenty-three years have passed and it is still true that, as Ray Stannard Baker then pointed out, “Industrially, we have arrived at the state of the Central American Republics politically-a government of successive revolution.”

———-

[Emphasis added.]

-re Elizabeth Shapleigh, M.D., see:

(scroll down)

Occupational Diseases in the Textile Industry

-for Speech by Vida Scudder, see:

“Professor’s Plea: Living Wage for 1912 Textile Strikers”

-By Dana Rubin

https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2020/03/04/professors_plea_living_wage_for_1912_textile_strikers.html

Mar 5, 1912-Boston Globe-Wellesley Professors at Lawrence Colonial Theater Mar 4th

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/97802633/mar-5-1912-boston-globe-wellesley/

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/97802728/mar-5-1912-boston-globe-wellesley/

Julia Vida Dutton Scudder (1861–1954)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vida_Dutton_Scudder

https://www.religioussocialism.org/vida_dutton_scudder_a_voice_from_the_past_speaks_to_the_present

https://www.marxists.org/archive/scudder/index.htm

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bread and Roses – Judy Collins