—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Saturday July 29, 1911

Paul Kellogg on the Defeat of the Westmoreland Miners’ Strike

From The Survey of July 29, 1911:

WESTMORELAND STRIKECALLED OFF

PAUL U. KELLOGG

After sixteen months, during which their strike was kept up in the heat of summer and the cold of hillside camps in winter, the men have given in in the Irwin-Greensburg field of western Pennsylvania. The main causes underlying this remarkable struggle, which President Hutchinson of the Westmoreland Company called civil war, were described in The SURVEY for December 3, 1910. Since then articles have appeared in Grit, Collier’s, the Philadelphia North American, and elsewhere, and this spring a hearing was held before the rules committee of the House at the instigation of Congressman Wilson.

The hearing did not lead to a federal investigation as the labor men had hoped, and this may have had some influence on the action of the international executive board of the United Mine Workers of America at Indianapolis on June 27. The board voted that there were no longer funds to continue sending $20,000 each week to Greensburg. According to a correspondent, two factors decided this action: the slack coal market has cut down mine work all over the country, and the members have been slow in sending in the tax which supports the striking miners and their families; in the second place, “a million dollars has already been expended here, with no immediate hope of settlement, and by losing this strike they will not endanger the miners’ chances in other strike zones, in Colorado especially, where another expensive strike is on .”

Following the action of the international board, a meeting of leaders was held in Greensburg and the strike was declared off on July 5.

No demands were made and no concessions were offered regarding any of the issues for which the struggle had been kept up for over a year. These on the one hand had related to checkweighmen, the rate of pay, hours, payment for dead work, and other reforms in the everyday dealings of the workmen with their employers, which to their minds would put them on an equal footing with the neighboring Pittsburgh district; and on the other hand, had related to recognition of the union.

There had been no labor organization in the district. During the first twelve months the strike played a part in the internal feud between President Feehan of District No. 5, and former President [Thomas] Lewis of the international, and when the latter was succeeded last spring by President White the expectation was that the strike would be prosecuted with the utmost vigor in line with Feehan’s policy. Some of the most skillful organizers in the country were put into the district: almost military discipline was developed in the labor camps, and the men were set to work in various ways to keep them occupied.

By the end of the first six months of the strike the larger operators had been able to resume getting out coal by means of strike-breakers, protected by guards; but the smaller properties were closed and the pickets kept making inroads among the new men, getting them to quit work and make common cause with their predecessors. There were defections also, no doubt, from the strikers. But it is proverbial that strikebreakers demand high pay and abuse a mining property, while guards are drones altogether and are even more costly. Report has it that the long months of struggle had sorely taxed the resources of the operators, when the slack coal market saved them. Had there been brisk business, it is asserted, they would have been forced to make concessions so as to meet the market competition.

The Pittsburgh Gazette-Times quotes the operators as saying that the strike-breakers now at work have settled permanently in the mining towns, and will not be removed; therefore they are unable to state how many of the strikers will be given work. The same report states, however, that the operators gave work to all they could accommodate and “in several instances operations were increased to make room for men who had not wielded a miner’s pick for sixteen months and who were in dire straits as a result.”

One estimate states that 5,000 men have been taken back to work, while 2,500 are out of employment. Altogether 18,000 men went out last year, the balance leaving the district in the interval.

In this shifting character of the mining population lies an explanation both of how it was possible for the union to keep up the struggle so long and why it failed in the end. The strikers were in large part immigrant workmen. Many had no roots in the mining towns, living in boarding-boss establishments in the company houses. They could pull up stakes and look for work in adjoining districts, thus relieving the strike commissary. At the same time not only funds, but leadership had to be drawn from the outside, for this was not the settling down of a resident work-people to a long-continued struggle in the towns they had grown up in. Moreover the coal companies could import men of even less stability and no local loyalties at all; could empty their company houses, and attempt to start fresh with new communities and new working shifts. In other words, this was but another chapter in the long process which Pennsylvania bituminous coal fields since the early 80’s, as analyzed in the reports of the Federal Immigration Commission. With the change of pick-mining to machine work the proportion of unskilled and semi-skilled workmen has gone up by leaps and bounds and immigrant workmen have filled these jobs.

From the strike standpoint the chief characteristic of such jobs is the “replaceability” of the men who hold them. From the strike standpoint, the chief characteristic of immigrant labor is its fairly inexhaustible supply. What is true in strike time, when an organization of men matches its strength with an employing company, is even truer in the everyday bargaining of leaders with foremen.

Herein lies something of the explanation of why within ten years after the immigrants from eastern Europe came into the Connellsville field, in the ‘8o’s, the aggressive labor organizations there had been driven out during a succession of strikes, why the English-speaking miners migrated to Oklahoma and Kansas, why earnings in those fields average half a dollar a day more than in the western Pennsylvania districts from which they came. Herein lies the explanation of the fact that these strikers of 1910 were some of them the strike-breakers who had been brought into Greensburg and Latrobe and Irwin in 1890, displacing the older inhabitants. Herein lies the explanation of the newspaper statement that “the men now at work have settled permanently in the mining towns.”

This Westmoreland strike was then in a sense a union effort to win back lost territory through organizing the new men on the ground, in the belief that they had reached a point where they felt what to a labor man are rights and grievances.

In the early days of the struggle, especially, there were clashes between these men who now had a toe-hold in the district and the greeners brought in under guard. Charges of violence are made by the mine superintendents against the processions of undisciplined, half-organized strikers who marched the country roads. Similarly, the undisciplined, half-responsible deputies who brandished guns in protection of company property were charged with the use of force-seven men had been killed by deputies (two of them fellow-deputies in drunken rows) in the six months preceding THE SURVEY’s investigation last fall.

The companies charged the union leaders with inciting their followers to violence; but it was the degree to which the American, Welch, Scotch, Irish, Italian, and Slovak organizers kept their men in hand-immigrants not of their own recruiting, but men who had been gathered by the employment agents of the mines—which impressed the investigators. And as in the case of the McKees Rocks strike of two summers ago, which failed like this one, it is the capacity for organization, for long-continued and stubborn assertion of the ends they want, manifested by what might be called the Slavs of second wind the language, industrial ambitions and movements of their fellow-Americans-which is the significant fact in its bearing on the future in this western Pennsylvania labor field and in America generally. In marked degree these two strikes bear out the prophecies as to the Slav workmen made in 1908 by Prof. John R. Commons and Peter Roberts in their reports for the Pittsburgh Survey .

[Photographs and emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

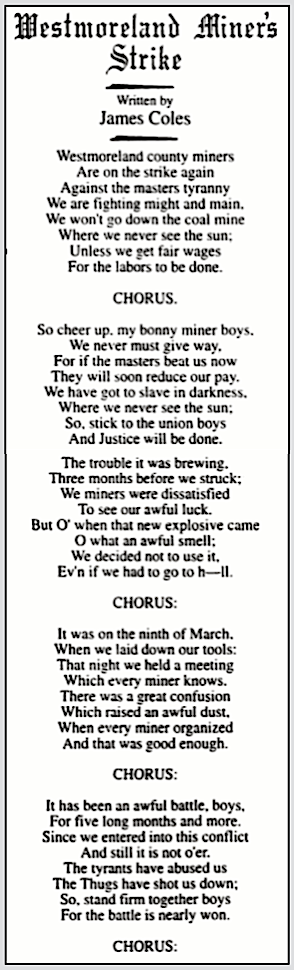

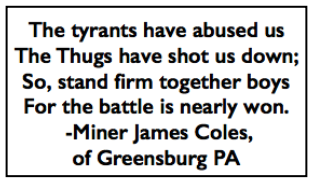

Quote fr Westmoreland Strike by James Cole

-written about Aug 1910, Greensburg PA

The Survey

(New York, New York)

-Apr-Sept 1911

New York Survey Associates, 1911

https://books.google.com/books?id=XZMJAAAAIAAJ

Survey of July 29, 1911

“Westmoreland Strike Called Off” by Paul Kellogg

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=XZMJAAAAIAAJ&pg=GBS.PA624

IMAGES

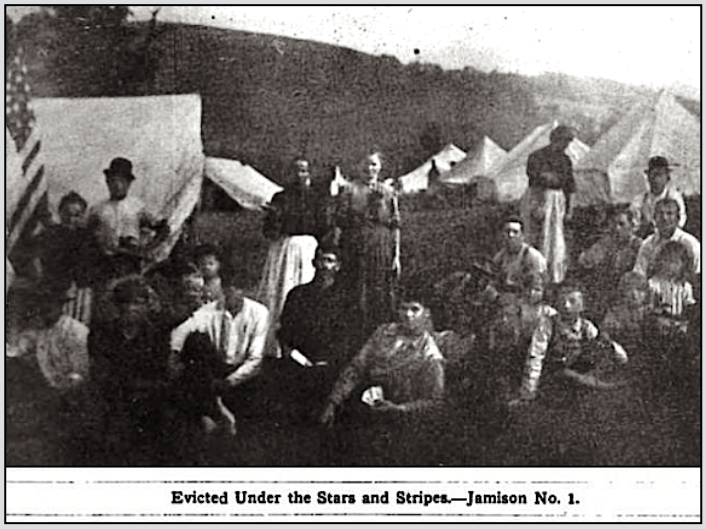

Westmoreland County Coal Strike, Camp of Evicted,

-ISR p101, Aug 1910

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8-05AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA101

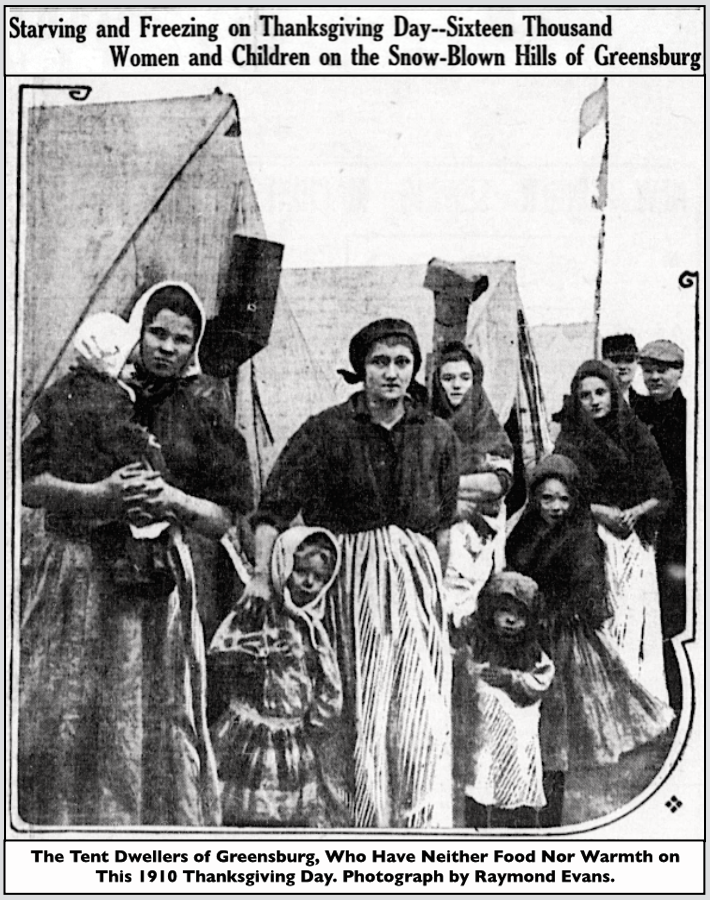

PA Miners Strike, Small, Tent Colony Greensburg, Thanksgiving,

–Seattle Star p1, Nov 24, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87093407/1910-11-24/ed-1/seq-1/

See also:

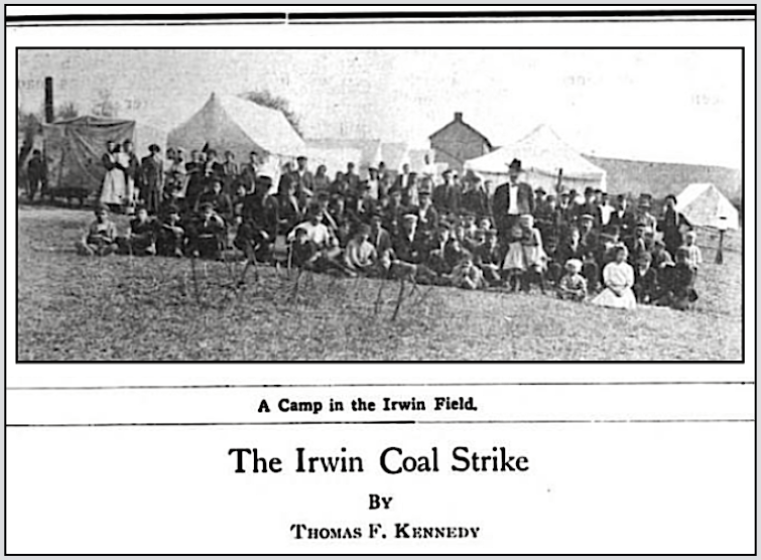

” Irwin Field Coal Strike” by TF Kennedy, ISR p99, Aug 1910

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8-05AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA99

Tag: Westmoreland County Coal Strike of 1910–11

https://weneverforget.org/tag/westmoreland-county-coal-strike-of-1910-11/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Westmoreland Strike by James Cole

Note: tune was not given for Coles’ Song/Poem

–Auld Lang Syne seems to work: