C’est la lutte finale

Groupons-nous et demain

L’Internationale

Sera le genre humain.

-Eugène Pottier – Paris, June 1871

Hellraisers Journal: Monday April 18, 1898

From London’s Social Democrat: the Story of an Old Communard

The following story of an old communard’s tribulations, in a small French village during the early 1880s, was begun in the April edition of The Social Democrat and will be continued in the May edition.

THE OLD COMMUNARD.

(Il en Était)

—–(From the French of J. B. Clément.)

—–

I.

One morning in the month of December, 1880, the omnibus which connected the station of —– with a little village at several miles distance, stopped before the door of a farm, on the threshold of which waited the farmer, his wife, and their two young children.

“Ah! Here he is! What happiness!” cried the two little ones, dancing, and clapping their hands with joy the while.

The farmer, followed by his wife, ran to open the door of the carriage and to assist a man of about sixty years of age to descend. He was of middle height, and was supported by a crutch.

“Good morning, father,” said the farmer, as he embraced the old man with effusion.

The farmer’s wife and the two children fell upon his neck and covered his face with kisses.

“Good morning! good morning! my dear children. Oh! how glad I am that I have arrived at last. The distance is not very far, but the time has seemed so long.”

“Breakfast is ready, father,” said the farmer’s wife.

“That’s good, my children; I believe I shall do it justice.”

” So much the better, father.”

And haltingly, walking in the steps of the old cripple, the whole family traversed the large farm yard and entered the dining room, where a good fire was crackling on the hearth.

After having made the acquaintance of the dogs, and handed over his crutch to the children, each of whom wanted the honour of its entire possession, the old man, aided by his son, who supported him under the arms, sat down to the table with the happy air of a man who feels an appetite and experiences the joy of finding himself in the bosom of his family.

* * * * * *

The arrival of the old man was an important event in the little village. The good wives when they heard of it made the sign of the cross, as if to exorcise some evil fate; the men muttered menaces, and the children expected to see the apparition of some ugly goblin.

The new-comer was, however, the best of men. He had a good and affable appearance, and his long white beard added to the gentleness of his physiognomy. But the excellent man was preceded by a frightful reputation. Only think of it! the monster was an amnistié of the Commune, and he had the audacity to come and live in this peaceful village at the house of his son, who had sufficient intelligence to brave whatever the gossips of the neighbourhood might say.

The son had received a good and solid education. He had by chance made the acquaintance, among his friends, of an amiable and intelligent peasant; he fell in love with her, and asked and obtained her hand in marriage.

An only daughter, at the death of her parents she inherited a small farm. The son of the amnistié having lost his mother, and his father being in New Caledonia, had nothing which bound him to Paris, so he became a farmer and had never regretted it.

He had two children, and desired no more; he worked for them, pledging himself to bring them up well, and give them a good education, and he and his wife charged themselves with their training.

—–

II.

The father, whom we will call Martin, was then sixty years old. A great age for a man who had suffered and struggled all his life, knowing the hardships of exile and prison, and the miseries of deportation and the pontoons.

Born in 1820, in the suburbs of the Temple, at the age of ten he had, like a true gamin of Paris, already taken his little part during the three days that it is agreed to call the ‘trois glorieuses.” During the reign of Louis-Philippe he was active in all the movements of the time, and in February, 1848, was, naturally, one of the first to take up arms, and one of the last to remain in the breach.

When the memorial insurrection of June broke out, he fought in every part of Paris. Wounded at the heroic defence of the Faubourg Saint Antoine, he was taken prisoner, and sent to the pontoons then to Africa, from whence, after three years, he returned to place himself once more among the few militants remaining faithful to the emancipatory ideas of Blanqui and Cabet.

The coup d’état of December, 1851, found him standing for the defence of the Republic. Captured with arms in his hands, at the Grange-aux-Belles Bridge, he was tried, sentenced to deportation, and dispatched to Cayenne, where he remained until the amnesty of 1859.

On his return to Paris he renewed his acquaintance with several friends, and continued to struggle on in view of the realisation of the ideas for which he had always fought, and for which he had so often risked his liberty and life.

He joined the group of mutuallists, the advanced men of that epoch. He contributed in a large measure to the foundation of the International. Tracked and pursued, he was again arrested and imprisoned with Varlin, Thiesz, Combaut, and other valliant men, whose devotion and energy ought to serve as a good example to the workers of our days, and call them to the sentiment of the duty that they seem to have too much forgotten.

* * * * * *

During his peregrinations the brave Martin had found time to take unto himself a wife. They had one child, the farmer whom we saw helping him to descend from the omnibus.

When the war of 1870 broke out Martin was then fifty years old, and his wife several years less.

Having to undergo a condemnation of two or three-months imprisonment, on account of his connection with the International, &c., he found himself liberated, on the 4th of September, simultaneously with the fall of the Empire, and the proclamation of the Republic.

Several days after he joined a batallion on march, and during the whole of that rude and tragic campaign he filled, to the admiration of all, his duties of soldier and citizen.

On March 18, 1871, he defended the hill of Montmartre against the troops and gendarmes of Vinoy. When the Commune, to the advent of which he had contributed so much, was definitely installed, he would accept no post, but took his place as a simple soldier in the ranks of the Federal troops. Always to the fore where danger threatened, he fought heroically until the 25th of May. His last position was at the barricade of the Place du Château d’Eau, where he received a ball in the thigh, which was not extracted until some time afterwards, and left him a cripple for life.

Arrested at his house, on the denunciation of a trader in the district, well-known for his Bonapartist sympathies, he was dragged to Versailles, then tried and sent to New Caledonia, where he remained until the amnesty of 1880.

His wife having died two or three years before this date, he found himself too old and too infirm to serve his cause usefully, or to find work, and he, therefore, accepted the hospitality which his son had offered him.

Here we have much condensed the services which Father Martin had rendered to the cause of justice, when we saw him arrive at his son’s house with his sixty years, his long white beard and his crutch.

—–

III.

The brave man was hardly installed when some impudent lads of the neighbourhood came and howled at the door of the farm: “Down with the Communard! To Cayenne with the old cripple!” Knowing the world in which he lived, the son, who had the same blood as his father in his veins, and who was no coward, thought that the best thing to be done was to let these manifestations wear themselves out.

Father Martin did not go out; he walked in the garden, or in the farm yard, with the children, and found that better than New Caledonia.

Thus he lived through the winter. When the spring came he attempted to go out with the little children, and walked to the village green, and there sat on a bank under the shade of an elm which had the reputation of being a tree of liberty planted there under the first revolution.

He arrived there without much hindrance, having only to endure on the way some dog-howls hurled after him, some spiteful glances of women and old men who sat on their doorsteps and muttered between their teeth, “He was in it,” meaning to say, “He was in the ranks of the Commune.”

But the news of the appearance of the old Communard had spread through the whole village; the children collected, and in order to get back to the farm he had to suffer the attacks and the insults, not only of the children, but also of the parents, who excited them.

“Down with the Communard!” howled some.

“Eh! you old cripple!” cried others, “there is nothing to steal here. What have you come here to do?”

“Ha! He was in the band at Vidocq!”

“And all cried in chorus—

“He was in it! He was in it!”

Some were insolent enough to pull his crutch, and others to attempt to lay hold of his beard. His, little children cried bitterly. Imperturbable and resigned, he embraced and consoled them, and continued on his way, thinking the while, poor sheep of Panurge! His son had also fallen a victim to the unjustifiable hatred that was shown to the father. No one spoke to him, and the malicious people of the place baptised his farm, “The Little Commune.”

Several months later a fire broke out in a farm situated at the extremity of the village.

“It is very curious, all the same,” insinuated certain gossips, “we never have had a fire in our village before; it is quite certain now that the old man at the Little Commune has brought us bad luck.”

“And who knows,” added others, “that this is not the work of his hands?”

“Mon Dieu!” interposed some cunning one, “perhaps he has done it with the petroleum that he has saved from the Commune time.”

Martin and his son let them talk on. But it was impossible for the good old man to go and think a little in the shade of his beautiful tree of liberty. He resigned himself, however, and kept to the house. Not meeting him in the streets, the enraged people attacked him in the house by throwing stones in his windows. He was compelled to change his room. At night they serenaded him with an air and words composed by a poet of the district, and terminating with “He was in it! He’ll not be in it any more!” The rural authorities, the gendarmes, and the municipality were well aware of these odious acts, but each one laughed up his sleeve, and took no notice.

Two long years passed away in this manner. The son had intended to leave the village, but the father dissuaded him from it, assuring him that one day all this scandal would terminate happily.

—–

IV.

The inhabitants of the Little Commune had, however, a friend and defender in the village whose existence they scarcely dreamt of. This was William, the smith, a great, pleasant fellow of some fifty years, who had served in the campaigns of Africa, and whose father had died decorated with the medal of Saint Helena.

Very often the smith took his evening pipe in the inn in company with the country people. He reproached them energetically with their conduct, and went so far as to tell them that at the first insult he would go out with a ploughshare and lay it about the bodies of the brawlers.

What have you to reproach the people of the Little Commune with?” said he. “A poor man has never applied to them and been turned away empty, but has always had food and lodging according to his need. The son pays his workers more than any other farmer. When anyone is ill, it is Father Martin who cares for them, and does not leave them to die as does your famous doctor whom you have to go two leagues distance to seek.

You reproach him with having been in the Commune! Do you know at all what that Commune was? Ah! I know it too well, and it fills me with remorse. At that period I was a soldier, and after having done our duty against the Prussians my regiment was sent against Paris.

Our officers told us that they counted on us, that we were going to be the saviours of Paris, of France, and of the Republic, by punishing the brigands who had filled the capital with fire and blood, and who pillaged and butchered women and children.

Like idiots I and my comrades believed our officers, and we were more

cruel towards the Parisians than we had been towards the Prussians. And we, children of the people, and of France, who, after the taking of Paris by treachery, have been robbers, incendiaries, and butchers of women and children.The order was to massacre, and we massacred. Ah, well! I regret it, and have often wept at its remembrance, for the Communards were better men than Thiers and his band, and the rascals and traitors who have betrayed France.

Plunderers! I have since known many Communards. They were all as poor as Job. Look at father Martin; has it enriched him? He has had a great deal of imprisonment, he has been to New Caledonia, he is crippled, and, if it were not for his son, what would become of him?

Endeavour, then, to bring peace to this good old man, and do not prevent him from dying in tranquillity. He has defended the ignorant, such as you, against the evil people who would crush them. He has defended those who have not enough to eat against those who have too much. If we had not had men such as he at the great Revolution you would not have a scrap of land to call your own, and would still be the serfs of the Château over yonder!

“To your health and to the health of father Martin,” cried the smith, as he raised his glass in the air and emptied it at a gulp.

The countrymen listened with open mouths and said amongst themselves: “We could spend the whole night listening to this William! He speaks even much better than our deputy.”

On one of these eloquent days the smith added:

To-morrow I will go and seek him, and I will accompany him to the green. I know that he will love to repose, to think, and to respire under our beautiful tree of liberty! That tree is more his than ours—he has defended liberty and the Republic, the poor old ma! As for me, I am Republican, nom de Dieu! And if to be Socialist is to be for the good of all, and for justice, then I am Socialist also! And if that displeases anyone, in spite of my fifty-two years I am still the man to reply to them. Long live the Republic and the Good!

Then he rose, filled all the glasses, and sang in a formidable voice:

The people are our brothers,

Our brothers, our brothers,

And tyrants our enemies!On these evenings William returned home satisfied, and yet discontented with himself—satisfied with having, as he called it, “driven a nail home” in the minds of the ignorant countrymen; discontented with having drawn arms against the Parisians. He denounced himself as a fool! brute! base soldier! food for powder!

His wife, knowing what this humour portended; took good care not to utter a word, and William went, swearing, to bed.

In the morning he would rise, heavy in head and oppressed at heart. He burned with the desire to run to Father Martin, fall upon his neck, and ask his pardon.

“For,” said he, “it is horrible! When I think that I might have had him in front of my rifle, and have killed so brave a man as that!”

A. E. L.

(To be continued.)

[Photograph added.]

SOURCE

The Social Democrat, Volume 2

A Monthly Socialist Review

-Jan to Dec, 1898

Twentieth Century Press, London, 1898

https://books.google.com/books?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ

SD -April 1898

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA99

“Old Communard”

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA124

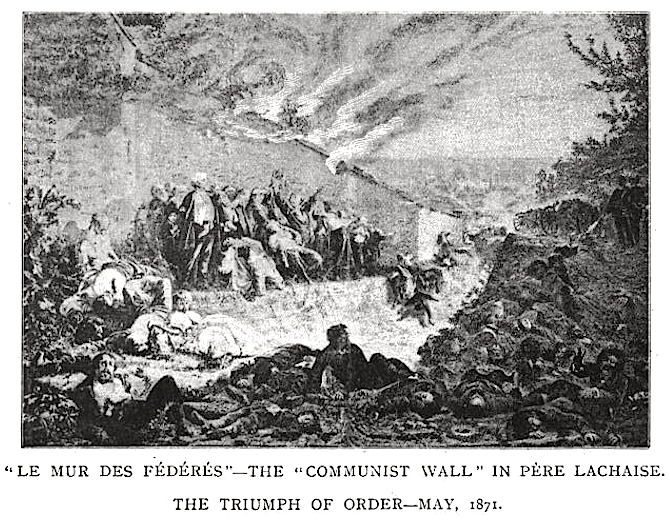

IMAGE

Triumph of Order over Paris Commune May 1871, ScDem Mar 1898

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA66

See also:

Hellraisers Journal, Thursday March 31, 1898

Paris Commune Celebrated Annually by Socialists

From The Social-Democrat: Anniversary of Paris Commune Celebrated by Socialists World-Wide

Tag: Paris Commune

https://weneverforget.org/tag/paris-commune/

Jean Baptiste Clément

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Baptiste_Cl%C3%A9ment

La marseillaise de la Commune

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_marseillaise_de_la_Commune