———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Thursday July 29, 1920

“The Mexican Revolution” by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman, Part I

From The Liberator of July 1920:

The Mexican Revolution

By Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman

[Part I of III.]

AFTER ten years of practice any people should understand quite thoroughly the technique of conducting a respectable, eat-out-of-your-hand revolution. The Mexican revolution which brought a new régime into power some few days ago was orderly, efficient, easily successful. Less than a month from the day the sovereign state of Sonora raised the banner of revolt, the revolutionary army-el ejercito liberal revolucionario-galloped into the capital without the firing of a single shot.

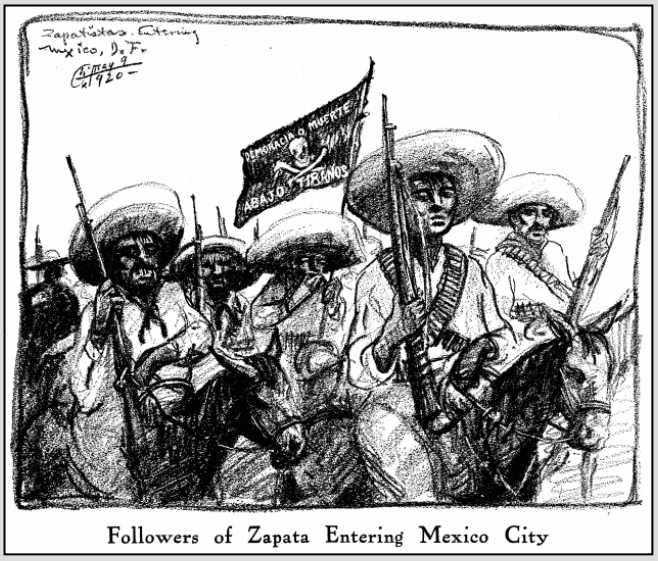

They looked strange-those men from the hills, on their lean, tired ponies, as they pounded down Avenida Francisco Madero, Mexico’s fashionable Fifth Avenue, dusty and ragged-colorful with great red and blue bandana handkerchiefs and vivid shirts, with flowers hung on their carbines, but eyes grim with purpose. Yet Mexico paid little attention to them. The stores were open; the honking automobiles crowded the flanks of their ponies; fashionable women went unconcernedly about their shopping. Only occasionally did they stop with a rustle of their silk gowns to gaze at the queer outlaw crew of sandalled Indians and Mestizos sweeping by beneath their great, bobbing sombreros.

During those first days I roamed the streets disconsolately-box seats at a Mexican revolutionary melodrama and no thrills. I tried to imagine the turnover as being a cross-your-heart-to-die proletarian revolution, but merely spoiled the afternoon wishing I were in Russia.

Nevertheless, I made the most of it; hired an automobile and dashed around town taking snapshots of generals-who were easier to find than soldiers-scoured the countryside looking for the victoriously approaching Obregon who was expected in the capital within forty-eight hours with an immense force, of which the bands of cavalry we had seen were the paltry forerunners. Early in the afternoon we burnt up the road to Guadelupe Hidalgo-that venerated religious mecca of Mexico five miles outside of the capital, whishing past red-cross machines speeding back from the wreck of one of the Carranza military trains that had evacuated the capital some twenty minutes before the rebels arrived.

Four of the eleven Carranza military trains had been stopped in the Valley of Mexico; one by the treachery of its commander who voluntarily surrendered it; a second by a few well-placed shots; a third by a smash-up made by a crazy locomotive let loose in pursuit like the grand finale of an impossible ten-cent movie thriller; and the last by the sabotage of the workers.

The last was the most significant. Although this revolution has been a cuartelaza, or military revolt, although the people have been so disillusioned during the past ten years as to be full of skepticism towards any government, the universal and bitter hatred of the peon and the worker towards the cruel Carranza military regime has been so strong that their sympathies have inevitably been thrown with Sonora, with Obregon, with the revolutionaries. Perhaps had the debacle of the Carranza rule not been so swift and so easily accomplished, this might have been a new revolution by the people.

Yet even so there is no assurance that this revolution will be any more successful than those, that during the last ten years have passed like great suffocating and devastating tidal waves over the heads of the very ones who have made them, or at least been the cause of them-the bewildered, helpless, idealistic Mexican people-except for one thing: this revolution brings for the first time since the downfall of Diaz a real welding of the rebel movement and counts upon its side every man of decency and vision-such as it is-that has appeared in Mexican life during recent years-de la Huerta, governor of Sonora; Calles, leader of the Sonora revolt, and but a month previous a recalcitrant member of Carranza’s cabinet in the portfolio of Commerce and Labor; Alvarado, the State Socialist of Yucatan; Felipe Carrilo, president of the Yucatan Liga de Resistencia. Any social progress in Mexico depends, for the present, absolutely upon the calibre of the leaders. “Democracy” and “The People” are meaningless terms so far as politics go.

But already, a week and a half after the capital was taken, before a provisional president was elected, the new leaders began to see that the people got lands. I attended an enthusiastic ceremony in Xochomilco, a suburb of the capital, but yesterday, where 3,000 acres of the finest land in the valley of Mexico, the ancient ejidos or commons of the village, were returned to the Indians.

The French Revolution failed, from a constructive standpoint, because for over one hundred and seventy-five years the people had had absolutely no experience in local or national self-government, no training in cooperative and voluntary association; the Russian Revolution succeeded, not alone because it moved upon the afflatus of a great and consuming ideal, not alone because of the driving impetus of economic and historic forces, but because the, peasants of Russia had already tasted the flavor of local self-government, because they had already learned to work together in co-operatives and soviets. The Mexican is in the same situation as the French peasant of the eighteenth century, just as helpless in the clutch of ambitious and selfish personalities. The one good thing that the years of revolution have thus far brought the Mexican, is not land, not a better standard of living, for in both respects he is worse off than in the days of Diaz, but an abiding sense of freedom and conviction of his inalienable right to enjoy freedom. Part of this determination to attain true freedom has fortunately been expended in creating labor organizations, weak it is true, but promising. But as yet the people of Mexico, however frequently they make a revolution, or permit themselves to be used to make one must depend upon their leaders for the fruits.

The latent sympathy of the workers and the peasants is with the new movement because of the personnel of its leaders. The sabotage on the part of the railway workers is one proof of this latent sympathy. The Carranza train was stopped because some of the workers in the round house saw to it that one of the engine trucks would drop off within a few miles. It was the railway workers who helped Obregon to escape from the clutches of Carranza, and during the past month scarcely a military train has left the capital that has not been so sabotaged by the workers as to guarantee a break-down and a temporary blocking of the way. Also perhaps it is more than a coincidence that the workers of the textile mills of the Federal District went on strike during the revolution, and that a general strike was imminent in the capital just before the fall of Carranza. For even the poorly organized, uneducated workers of Mexico are beginning to discover that there are more effective ways of making a revolution than by bullets and self-slaughter.

It was to be expected that the workers would hate Carranza. There has never been an important strike in Mexico, but that Berlanga, Carranza’s sublimated office boy, has not sent federal soldiers to shoot down the workers or invoked or threatened to invoke the treason act.

In Yucatan the government troops have broken up with torture, murder, fire, and hanging, the great Liga de Resistencia, an organization having 67,000 men and 25,000 women members, paying a monthly dues equivalent to seventy-five cents. Its co-operative stores were looted, and machine-guns turned upon whole villages.

To the Yucatecan the red card of the Liga meant land and liberty. He had stripped his churches of their images, and had used the buildings for headquarters and meeting places for the League. He carried the card in the crown of his mammoth sombrero with the same religious veneration that he formerly carried his image of his patron saint about his neck.

When, therefore, the federal Colonel Zamarripa rode into a village, as he did into Mixupip, and announced to the villagers that they were to call themselves Liberales, or members of the government party, they demurred. In Mixupip he strung five of them up to the nearest trees as an example to the rest.

“Now, what are you?” he then bellowed.

The Indians, unshaken, naïvely pointed to the red, cards in their hats.

Colonel Zamarripa shot twenty-for a lesson!

In this way whole villages were wiped out, until 1,200 members of the Liga had been murdered.

Even the reactionary Mexican Senate protested to Carranza. Carranza retorted by making Zamarripa governor of the federal territory of Quintana Roo.

Aside from cutting off the heads of election inspectors and putting them on top of the ballot boxes; aside from threatening with death everyone who did not vote, and forcing everyone that did vote, to choose the government candidates, the Carranza government was quite honest, humane and enlightened in Yucatan.

Read what the daily paper La Revolución said last February about the governor of Oaxaca, one of the richest states of Mexico.

The governor Juan Jimenez Mendez is the protecter of lives and haciendas (in Orizaba). That governor assassinates, orders assassinations, burns towns, hangs pacific townspeople, steals the municipal funds to maintain his automobile and fine living. As a result many employees die of hunger because he does not pay the salaries honestly earned. He-Jimenez Mendez, like a ridiculous dude, changes his suits daily, organizes gambling, and, with his gang of followers, becomes obsequious to anyone who brings gold. He takes trips when and where he pleases, and fails to come to his office for two, three, or as many as five days.

The fields are stripped of their fruits, private persons are attacked during the early hours of the night within three or four streets of the state capital building….

This “misgovernment” is surrounded by pimps, vulgar, elegant women, ignorant idlers….

———-

*Robert Haberman, formerly of New York and a member of the Socialist Party, has spent the last few years in Mexico, organizing co-operatives in Yucatan. Carleton Beals is another New York Socialist whose name will be familiar to many of our readers. We hope to print other interpretations of the Mexican situation in the near future.

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Zapata Die Fighting, Wikiquote

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-July 1920

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/07/v3n07-w28-jul-1920-liberator.pd

See also:

Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_Revolution

Álvaro Obregón Salido, 1880-1928

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81lvaro_Obreg%C3%B3n

Emiliano Zapata, 1879-1919

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emiliano_Zapata

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Las soldaderas – Revolución Mexicana