———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday December 8, 1920

Max Eastman: “John Reed sacrificed a life to the revolution…”

From The Liberator of December 1920

-“Fog” by John Reed:

———-

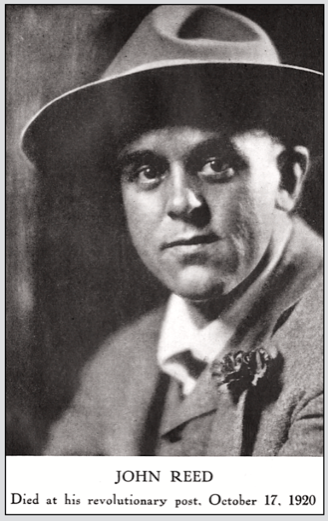

JOHN REED

[-from Speech by Max Eastman.]

WE have been reading in the great newspapers of this city the last few days very appreciative accounts of the life and character of John Reed. They have permitted themselves to admire his courage and honesty and the great spirit of humorous adventure that was in him. They permit themselves to admire him in spite of the fact that he died an outlaw and a man wanted by the police as a criminal. They admire him because he is dead. But we speak to a dIfferent purpose. We pay our tribute to John Reed because he was an outlaw. We do not have to examine the indictment, or find out what special poison the hounds of the Attorney-General had on their teeth against John Reed. We know what his crime was-it is the oldest in all the codes of history, the crime of fighting loyalty to the slaves. And we pay our tribute to him now that he lies dead, only exactly as we used to pay it when he stood here making us laugh and feel brave, because he was so full of brave laughter. Our tribute to John Reed is a pledge that the cause he died for shall live.

He would not want us to be very solemn or tearful in talking about what he was. He always knew there was something humorous about the amount of trouble he stirred up wherever he went. He knew that he was a very unusual phenomenon, but I am not sure that he knew just what it was, besides his literary gifts, which made him so unusual.

John Reed belonged to a peculiar class of people who are known as the intelligentsia, and he was uniquely distinguished among the members of that class by the fact that he possessed a great intelligence. You will notice a rumor in the morning’s papers that in Russia they have had to establish a special institution in Moscow in order to “take care of” the intelligentsia. And I judge from what I read about it that it is something similar in its general character to a home for the feeble-minded. For one of the conditions of admission is a solemn agreement upon the part of the inmates that they will “withdraw from all participation in Russia’s affairs”-at least they will withdraw until the crisis is past, and everybody feels sure that their intelligence is not going to do any harm.

It is strange that these people who specialize in idealism should be just the ones that you have to put out of the way when you set out to realize an ideal. It is because they are so emotionally excited about ideals that they have no energy, and no passion, left with which to confront facts, or with which to define and pursue an historic method by which it might be possible to pass from the facts to the realization of their ideal. That is the trouble with them all. And the thing that made John Reed’s character so unusual in the life of our times is that although he was gifted with the power to use ideas emotionally, and paint them for the imagination with colors of flame-he was a poet, he was an idealist-nevertheless he was never deluded by the emotional coloring of ideas into ignoring their real meaning when translated into the terms of action upon matters of fact. He knew the cold tone of voice in which a scientist says what things are. He knew the hard mood in which a captain of industry says how things can be achieved. He was a poet who could understand science. He was an idealist who could face facts.

You all know how Jack Reed came out of Harvard College, universally acclaimed as a wonder-boy, with enough verbal ingenuity and imaginative fertility to fill up the newspapers of two hemispheres, and save the world for democracy with his own solitary typewriter. But he never to my knowledge uttered one single word of the solemn ideological bunk which had been fed to him in that institution. From the day of his graduation he was perfectly willing to let the world of democracy go to smash, and inside of a year, and a half he came down to my house one morning to see if I knew of anything he could do to help it along. We were just starting The Masses at that time, and we didn’t have anybody to write for it. All we had was a very celebrated group of artists, an editor, and a financial deficit that was large enough to give promise of a very momentous enterprise. I cannot help laughing when t think what a whirlwind of jokes and paragraphs and projects and ideas and energy and enthusiasm and poetry and bad judgment Jack Reed brought into those editorial meetings. But he also brought with him a beautiful little story that is a very jewel of reality in American fiction. And it was the arrival of Jack Reed with that story and that enthusiasm, more than any other thing, that convinced us that we had to have a magazine like The Masses whether it was possible or not.

Jack was just beginning at that time his phenomenal career as a popular journalist, and I had the opportunity to watch the impulse of his life develop at the same time in two directions which were fundamentally opposed to each other, and between which at some culminating moment he would inevitably be compelled to choose. On the one hand, because of the inexhaustible fertility of his pen, and because of the great boyhood spirit of world-adventure which everybody loved, all the newspapers and popular magazines in the country threw their doors wide open to him. They competed for his name, for his stories, the accounts of his adventures in politics, in war, in romance, until both in terms of cash payable and in terms of glory, John Reed stood at the very top of the profession of journalism in America. He was commonly acknowledged to be the greatest war-correspondent in the United States when the war of the world began in Europe. You can imagine the opportunity that this offered to him. And he was not only a war-correspondent, he was not only a journalist. He was also a poet and a writer of fiction and drama that was recognized beyond the popular magazines, in those more solemn institutions that are supposed to preside over the literary art of the period. There was no single point or phase of success or profit or contemporary applause in the literary world, which John Reed could not at that time have legitimately aspired to, and claimed for his own.

But during these same years there had been growing steadily in his breast a feeling of revolt against the contemporary world, against the conditions of exploitation from which our journalism, and what we call our art of literature, springs, and which it justifies, and over which it spreads a garment of superficial and false beauty. There was growing in his breast a sense of the identity of his struggle towards a great poetry and literature for America, with the struggle of the working-people to gain possession of America and make it human and make it free. And so all through those years when the offices and the drawing-rooms and the coffers of the magnates of capitalist journalism were opening to him, and his name was becoming a synonym for bold romance and light-hearted adventure all over the country, Jack Reed was faithful to our little revolutionary magazine that paid him nothing and gave him about ten thousand readers. He never failed with his contribution. Wherever he went, he never forgot to give us a story that was better than the one he sold to his employers. In that way he kept those two contrary streams of achievement running together as long as he could.

Then, almost at the same moment, war came to America, and the active struggle for a proletarian revolution began in Russia. And John Reed was confronted, as every man of free and penetrating intelligence was confronted, with the choice between popular and profitable hypocrisy in the capitalist journals, and lonely and disreputable truth in the revolutionary press. And he chose the truth. Way over the heads of the American proletariat, and beyond any vision that they had in their eyes, he chose to identify his interest with their interest, and his destiny with their ultimate destiny.

John Reed sacrificed a life to the revolution, not only in Moscow in 1920, but in America in that winter of 1917. And if there is any special tribute I can add to that of these other friends who were active with him at a later time, it is a testimony to the splendor and gayety and wealth and magnificence of the life he sacrificed. All that this contemporary world has with which to tempt a young man of genius, he renounced, when he fell in with the humble ranks, and accepted the bitter wages of a soldier of the revolution.

I should be sad if I thought that John Reed’s memory as a poet would die altogether, because he chose to make a great poem of his life. But I do not think it will. I always used to tell him, when he felt a little sad because he was not doing any creative writing, that, whatever he might do in the future, he could be happy in the thought that he had already written one of the few real poems in American literature. And I fully believe that, side by side with the memory of his magnificent gift of life to the cause of freedom, there will abide in the minds of thoughtful men and women in the free world that is to come, his beautiful poem, which he called “Fog,” but which is almost a poem about his own death.

I cannot say anything half so beautiful about John Reed’s death as what he has said in that poem. And I do not want to say anything more. Those magnetic words will remind you that it is not only a great laughing, lion-hearted fighter for truth and the revolution, that lies buried among the first heroes under the wall of the Kremlin, but it is also a true genius, who could have done almost anything else that he pleased.

(From a speech by Max Eastman at the John Reed Memorial Meeting in New York on October 25th.)

[Photograph and emphasis added.]

———-

———-

From the Appeal to Reason of July 11, 1914:

John Reed on Ludlow

(A remarkable article on the Colorado war, written by John Reed, appears in the Metropolitan for July. The following extracts from Reed’s article are especially interesting, now that the Camera and other plute papers are being circulated in the interest of the mine owners:)

On the morning of the 17th of October [1913], a body of armed horsemen galloped down the Ludlow road and dismounted in a railroad cut near the colony. At the same time Felts’ armored automobile appeared from the direction of Trinidad, swung around and trained its machine gun, immediately on the tents. Astonished and terrified, the strikers swarmed out, dragging their guns with them, but a a guard named Kenedy, afterward and officer in the militia, approached with a white flag, shouting:

“It’s all right, boys; we’re union men.” And as the strikers lowered their guns, he said:

“I want to tell you something.” They clustered around him to hear what he had to tell them. He cried suddenly: “What I wanted to say was that we are going to teach you red-necks a lesson!” and, lowering the white flay, he dropped on the ground. At the same time the dismounted horsemen fired a volley into the group, killing one man instantly. In a panic, the strikers poured back to the tents, across the field to a gulch where they had agreed to go in case of attack, and as they ran the machine gun opened up on them. It riddled the legs of a little boy who was running between the tents, and he fell there. The strikers immediately began to fire back, and the battle kept up from two o’clock in the afternoon until dark. Every time the wounded boy tried to drag himself in the direction of the tents, the machine gun was turned on him. He was shot not less than nine times. The tents were riddled, the furniture in them shot to pieces.

* * *

Guards Boasted of Deed.

I went to Ludlow next day [after federal troops arrived, May 1914] to see the federal troops come in and the militia leave. The tent colony, or where the tent colony had been, was a great square of ghastly ruins. Only a few were in uniform, for many of them were mine guards hastily mustered in. As the regulars left their train one militiaman said loudly, in the hearing of the militia officers: “I hope these red-necks kill a regular so they will go in and wipe out the whole bunch. We certainly done a good job on that tent colony.”

* * *

“Better” Element with Strikers.

Nine out of ten business and professional men in the coal district towns are violent strike sympathizers. After Ludlow, doctors, ministers, hack-drivers, drug-store clerks and farmers joined the fighting strikers with guns in their hands. Their women organized the Federal Labor Alliance, which is to spread all over the country, even among women whose husbands are not union men, to provide food and clothing and medical attendance for workers on strike. They are the kind of people who usually form law and order leagues in times like these; who consider themselves better than laborers, and think that their interest lie with the employers. Many Trinidad shop keepers had been ruined by the strike. A very respectable little woman, the wife of a clergyman, said to me: “I don’t see why they ever made a truce until they had shot every mine guard and militiaman, and blown up all the mines with dynamite.”

* * *

Children Burned Alive.

Lucia Bartellotti [Bartolotti] rocked slowly backward and forward, the tears running down her cheeks; they said she had been crying steadily for a week and could not sleep. She burst out monotonously, as one recites a piece:

I can’t remember nothing. I am so terrible and the shooting all the time, and me try to get down in our cellar under the tent. And then Mis’ Fyler comes and says:”For God’s sake, go down the well; they are gong to kill all the women and children!” When I come up again in the night, the tents burning and women and children burning alive, screaming, and I don’t know what else. My husband is shot in the back when he is running away because he does not know the customs of this country; and why they should shoot at us, God knows.

* * *

Shot Down as They Ran.

I asked her how it happened.

We sleep late in the tent colony because we have no work to do, and I am just getting the children’s breakfast when my husband comes saying: “They’re going to attack the tent colony, and to go.” I say: “Wait until I get the children’s breakfast.” “Never mind,” he says, “get down cellar.” Bed not made. Breakfast burning on stove. But there is no time. We pull the bed outside and go down under the floor, and just then all the bullets in the world come through the tent and break the oatmeal pot on the stove and the oat meal run all over and get burned, and smash the mirror on my bureau. Then Mis’ Fyler come and I start. I got seven children-my God, it’s hard to make them go!-and they shot us while we run and shoot through my dress. I try to say good-by to my man, and I can’t see him because he is gong the other way so the melish will shoot him and not shoot us. There are two shot men in that well and they bleed…

* * *

Called Woman “God Damn Red Neck.”

Maria Czekovitch dragged her little girl up to be interpreter:

My man was killed at Tabasco mine two months before the strike, and the company pay me $20 to buy a coffin with, and then throws me out because they do not want me. I go to Ludlow tents and take boarders there. I am very rich woman because I have no children. In two years I save $125 and I have my husband’s two suits of clothes and his watch which cost $30 in Denver. I am lying in the pit in my tent when the militia comes in the evening after the shooting all day, and they smash open my trunk and take my husband’s clothes and watch, and militiaman puts his hand in my breast and takes out my money and puts it into his pocket and hits me with the butt of his gun and says: “I don’t care whether you get burned or not, you God damn red neck.”

* * *

Rockefeller Approves It All.

I want to add one significant fact for the benefit of those who think that Mr. Rockefeller and the coal operators are innocent, though misguided. At the triumphant conclusion of the legislative session, it is said that Mrs. Welborn, wife of the president of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, told her friends of the “lovely telegram” her husband had received from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. It read according to Mrs. Welborn:

Hearty congratulations on the winning of the strike. I sincerely approve of all your actions, and commend the splendid work of the legislature.

[Emphasis added]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote John Reed, 10 Days Chp III, 1919

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=-voDAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA42

The Liberator

(New York, New York)

-Dec 1920

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/12/v3n12-w33-dec-1920-liberator.pdf

Appeal to Reason

(Girard, Kansas)

-of July 11, 1914, page 2

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/appeal-to-reason/140711-appealtoreason-w971.pdf

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67314881

IMAGE

John Reed, Liberator p9, Nov 1920

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/11/v3n11-w32-nov-1920-liberator.pdf

See also:

December Liberator, page 9 (link above):

“Soviet Russia Now” by John Reed

Tag: John Reed

https://weneverforget.org/tag/john-reed/

John Reed-Internet Archive

https://www.marxists.org/archive/reed/index.htm

The Masses, Jan 1911 to Nov-Dec 1917

http://dlib.nyu.edu/themasses/

Index, pages 81-2:

http://dlib.nyu.edu/themasses/the_masses_index.pdf

July 11, 1914, Appeal to Reason-John Reed on Ludlow

-extracts from Metropolitan Magazine, Parts I & II

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/64876957/july-11-1914-appeal-to-reason-john/

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/64877027/july-11-1914-appeal-to-reason-john/

From the Metropolitan of July 1914

https://books.google.com/books?id=KpdNAAAAYAAJ

https://books.google.com/books?id=ke5HAQAAMAAJ

-Index

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x030708269&view=2up&seq=1

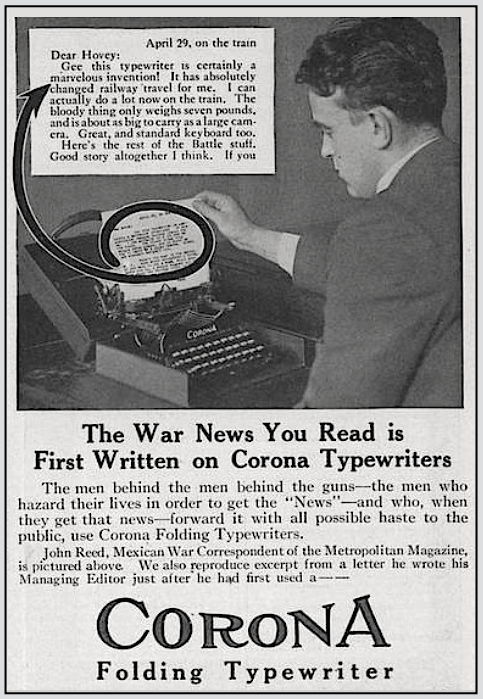

-page 11-The Colorado War

-page 23-With Villa on the March

-page 67-John Reed featured in Corona Typewriter Ad

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

International -“Reds”